-

The Military Heritage of Venice’s Pigeons

Venice is famous for its pigeons. They’re everywhere, and tourists expect to see them. A special haven for Venice’s pigeons is Piazza San Marco, the city’s principal public square. Before the 20th century, San Marco’s pigeons were highly regarded, even considered sacred. Several origin stories have been advanced for these pigeons, but, for our purposes, we at Pigeons of War favor one legend attributing a martial heritage to these birds. The most detailed account of this myth has been reproduced below:

On the heels of the Fourth Crusade, the Republic of Venice purchased the island of Crete from Boniface, the Marquis of Montferrat, in 1204 after promising to support his acquisition of the Kingdom of Thessalonica. Not everyone was happy with this transition. Some of the native population in Candia, the island’s most important port, resisted their new overlords. Raniero Dandolo, son of the Venetian Doge Enrico Dandolo and an Admiral of the Venetian fleet, initiated a blockade of Candia in response. The blockade was supported by a Genoese fleet under the command of Enrico Pescatore, the Count of Malta. Long-time rivals, Venice and Genoa were ostensibly allies at this point. Yet, some of Dandolo’s officers noticed that a flock of pigeons were flying towards the Genoese ships. Intrigued, Dandolo ordered for some of the pigeons to be captured the next time they flew in that direction. When they appeared again, Dandolo’s men shot down 7 or 8 of them with arrows. Upon inspection, each pigeon had a letter from the Candiotes to the Genoese secured to its wing.

Dandolo stormed Candia the next night, driving out the Genoese. Soon, he had control of the whole island. While exploring the now vacant governor’s palace, the Venetians found a number of pigeons. Dandolo shipped them to Venice with news of his victory. Grateful for the role the pigeons played in Dandolo’s conquest, city officials treated the birds with great honor, allowing them to dwell at Piazza San Marco.

Over time, San Marco’s flock of pigeons multiplied into an enormous colony. A 19th century tourist described their dominion over the Piazza and the city at large:

They rest at night in the laces of the palaces and the cornices of the great cathedral, on triumphant columns and arches and in the airy arcades of the Campaniles. They nestle with the winged lions and dart noiselessly through the churches. They brush the sacred altars and the tombs of kings and doges and bishops. They walk the marble pavements in groups and in hundreds, unmolested among throngs of passers. They play with the children and fly up on your cafe table for their share of the cake or water.

Undoubtedly, this increase was facilitated by a religious tradition dating back to the Middle Ages. Every Palm Sunday, the priests of San Marco released imported pigeons with weights tied to their wings over the Piazza. An Easter gift from the Doge to his citizens, most of those birds were easily caught by Venetians and eaten. The few survivors, however, were allowed to reside at San Marco, as they were believed to have earned the protection of the saint. After centuries of cross-breeding, the pigeons had developed into a stunning bird by the 19th century. One observer described their traits in almost rhapsodic terms:

[They] are black, and white (or grey) with pink eyes and red feet. A beautiful green collaret surrounds the throat; the body is quite white under the wings. Some of them have white tails; whiter than the snow which falls on the summit of the Apennines; and opal or topaz eyes, which change their tints a thousand times a day.

Meanwhile, the city’s generosity toward the Piazza’s pigeons persisted. Every day at 2 pm, an official rang a bell, alerting the birds that it was supper time. Without fail, the pigeons would swarm San Marco in search of the official’s grain. Aside from providing them food, Venetian officials also imposed strict laws guaranteeing the birds’ safety. If anyone harmed a pigeon, he or she would be arrested. For first-time offenders, they’d be fined; for repeat offenders, a trip to prison awaited them. Venetian citizens, for their part, viewed San Marco’s pigeons as sacred—it was not uncommon for individuals to leave legacies for their care or request saintships for them in the local calendar.

In 1848-49, the Piazza’s pigeons, not unlike their ancestors, found themselves recruited for wartime service. A possession of the Austrian Empire since 1797, Venice revolted in 1848, forming its own state, the Republic of San Marco. The Austrians eventually initiated a blockade of the Venetian Lagoon and bombarded the city. Throughout the blockade, the feeding of the Piazza’s pigeons continued unabated, even though the city’s population was starving. Some of them even carried messages out of the city in an end-run around the blockade. It was only in the last days of the conflict that a few individuals resorted to the unthinkable and ate some of San Marco’s pigeons. In August 1849, the Republic surrendered to the Austrians, becoming a Hapsburg province for 17 more years.

By the modern era, the city’s pigeons had lost their luster. Tourists still loved them, and a thriving industry had popped up, supplying visitors with corn to feed the birds. City officials, however, were frustrated that the city’s pigeon population had ballooned to 60,000, even though the city could only accommodate about 2,400 of them. Pigeons were blamed for damaging art and architecture—their highly acidic poop allegedly caused structural damage as it seeped into fissures, while their constant scratching and pecking damaged marble monuments. They also, per officials, spread disease and attacked the customers of hoteliers, restaurateurs, and other merchants. Pigeon advocates chalked most of these issues up to pollution and reckless tourists.

Much to the chagrin of tourists, in 1997, Venice banned the feeding of pigeons everywhere except for at Piazza San Marco. Naturally, this caused the city’s pigeons to congregate en masse at the Piazza. In 2008, the city finally banned the feeding of pigeons at San Marco. Violators would face a €500 fine. While the ordinance merely annoyed tourists seeking pictures with the pigeons, it carried with it serious economic consequences for the Piazza’s 19 licensed bird seed vendors. Before the ban, vendors had offered tourists 3.5 ounces of corn for $1.30. On a good day, a vendor could clear more than $100. Outraged by the ban, the vendors argued that most of the damage to the Piazza was caused by smog. Vendor Gianni Favin noted the pigeons’ legacy at San Marco: “There have been pigeons in St. Mark’s Square for a thousand years,” he angrily remarked to the press. “To see the piazza without pigeons is like seeing a tree without its leaves.”

Vendors and tourists weren’t the only figures angered at the ban—animal rights groups vigorously protested as well. Shortly after the ban’s enactment, a “band of animal lovers armed with skull-and-crossbones flags” cruised up to the Piazza in their speedboat and hurriedly scattered 20 pounds of birdseed for the pigeons. They struck twice at dawn and once at midday, daring the police to fine them. But the stunts did not dissuade city officials from lifting the ban.

In the 14 years since the ban was implemented, mass colonies of pigeons continue to reside at Piazza San Marco. Some tourists still feed them on the sly, even though the fine has now been raised to €700. Having been a fixture since the 1200s, it seems that the legacy of San Marco’s pigeons will be a hard one to eradicate.

Sources:

- Ali, Shafqat. St Mark’s Square Pigeons Refuse to Budge. The Nation, 9 July 2018, https://www.nation.com.pk/10-Jul-2018/st-mark-s-square-pigeons-refuse-to-budge.

- Barry, Colleen. “Venice Confronts Its Vermin: 40,000 Pigeons.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 11 Sept. 2006, https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna14784143.

- De Roo, V. La Perre, Monographie des pigeons domestiques, at 268 (1883).

- Ginsborg, Paul, Daniele Manin and the Venetian Revolution of 1848-49, at 361, n. 75 (1979).

- Imboden, Durant. Pigeons of Venice. Venice for Visitors, https://europeforvisitors.com/venice/articles/pigeons_of_venice.htm.

- Perl, Henry, Venezia, at 63 (1894).

- “The Pigeons of Venice,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Dec. 23, 1868, at 4.

- “The Sacred Pigeons of Venice,” The Newbernian, August 16, 1879, at 4.

- Wilkinson, Tracy. “Animal Lovers Battle Venice over Piazza Pigeons.” Boston.com, The Boston Globe, 8 June 2008, http://archive.boston.com/news/world/articles/2008/06/08/animal_lovers_battle_venice_over_piazza_pigeons/.

- Wood, Sim. “Is It Okay to Feed Pigeons in Venice?”, Bird Buddy Blog, 2 Aug. 2022, https://blog.mybirdbuddy.com/post/pigeons-of-venice.

-

Pigeons in the Roman Military: The Siege of Mutina (44-43 B.C.)

At its peak, the military of Ancient Rome was without peer. Enterprising commanders developed advanced weaponry, employed innovative strategies on the battlefield, and implemented incredible engineering feats. With this expertise, one might wonder: did the Roman military ever utilize a pigeon post?

Before fully delving into this query, we first need to dispel a long-standing myth. It’s been frequently mentioned online and in print that Julius Caesar sent news of his victories in Gaul back to Rome via pigeons. Most recitations of this purported fact fail to cite any ancient sources for support. A few older sources attribute it to a “Prontius” or “Prontinus,” which is clearly a corruption of the name of Roman writer Sextus Julius Frontinus. While Frontinus did write about the use of pigeons during wartime (more on that later), he never mentions Caesar doing so. The notion that Caesar relied on military pigeons during his Gaul campaign has no basis in history.

Instead, credible sources writing in the latter-half of the 1st century describe pigeons being used at the siege of Mutina (modern-day Modena, Italy) in 44-43 B.C. That conflict was the culmination of a series of clashes between the Senate and Mark Antony—Caesar’s former right-hand man—in the leadup to the Second Triumvirate. Antony desired the governorship of Cisalpine Gaul (modern-day northern Italy), yet it was under the control of Decimus Brutus, an assassin of Caesar, and the Senate declined to remove him from office. Fed up with the Senate’s support of Brutus, in November 44 B.C., Antony gathered several legions and launched a siege against him at Mutina (Modena, Italy).

The Senate greatly disapproved of Antony’s actions, declaring him a public enemy in January 43 B.C. Seeking to curry favor with the Senate, Octavian–Caesar’s adopted son–and consul Aulus Hirtius combined their forces into a formidable army. With the Senate’s approval, their army advanced toward Mutina. On April 21st, Octavian and Hirtius attacked Antony’s troops, trying to create a route for supplies to pass through. A fierce battle broke out with mixed results for both sides. Both sides suffered nearly the same amount of casualties. Antony ultimately retreated from Mutina, but Hirtius died in combat. Nevertheless, the Republican faction declared victory over Antony’s forces.

Per our written sources, Brutus and Hirtius relied on pigeons during the siege to keep in contact with one another. Let’s take a closer look at these episodes, the first of which appears in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, written in 77 A.D. Encyclopedic in scope, Pliny’s work details the known world over the course of 37 books. In book 10, which is on the natural history of birds, Pliny mentions that:

[P]igeons have acted as messengers in affairs of importance. During the siege of Mutina, Decimus Brutus, who was in the town, sent despatches to the camp of the consuls fastened to pigeons’ feet. Of what use to Antony then were his intrenchments, and all the vigilance of the besieging army? his nets, too, which he had spread in the river, while the messenger of the besieged was cleaving the air?

A similar account surfaces in Frontinus’ Stratagems. Composed around 84 – 96 A.D., it’s a treatise on military strategies. Like Pliny, Frontinus claims that pigeons were used at the siege of Mutina, but attributes their use to Hirtius:

Hirtius also shut up pigeons in the dark, starved them, fastened letters to their necks by a hair, and then released them as near to the city walls as he could. The birds, eager for light and food, sought the highest buildings and were received by Brutus, who in that way was informed of everything, especially after he set food in certain spots and taught the pigeons to alight there.

Reading the sources together, a striking scene emerges: encircled by Antony’s troops, Brutus sends pigeons with vital information to Hirtius’s camp; receiving the latest despatch from Brutus, Hirtius attaches a reply to his birds and releases them near the city’s walls. If these reports are to be believed, then Brutus and Hirtius had devised a system for two-way communication in spite of Antony’s attempts to cut Mutina off from the world.

We at Pigeons of War are inclined to believe Pliny and Frontinus’ accounts. Throughout history, inhabitants of cities under siege have resorted to pigeons for communicating with the outside world—the sieges of Leiden (1574-75) and Paris (1870-71) are prominent examples. At Mutina, as in Leiden and Paris, the pigeons seem to have been employed only after other attempts at communication failed. Frontinus mentions that Hirtius had tried reaching Brutus by inscribing messages on lead plates, which were fastened to the arms of soldiers, who then swam across the Scultenna River. However, Antony put a stop to this when he spread nets over the river. The differing placements of the messages on the pigeons—on the neck for Hirtius and on the feet for Brutus—indicate that this was a hastily-assembled pigeon post, formed directly in response to siege warfare.

The only possibly erroneous information in these accounts is Frontinus’ claims that Hirtius’ birds flew toward tall buildings in Mutina in search of food and light. In reality, pigeons return to the area in which they were born and raised. For their pigeon system to have been effective, Brutus would’ve had to obtain pigeons from outside Mutina, while Hirtius would’ve needed pigeons raised within the city. This is plausible, however, as Pliny noted his fellow countrymen were obsessed with pigeons:

Many persons have quite a mania for pigeons–Building towns for them on the top of their roofs, and taking a pleasure in relating the pedigree and noble origin of each.

Perhaps pigeon fanciers in Mutina and the surrounding villages secretly exchanged their birds at the outset of the siege.

Thus, in answer to the question posed earlier, Roman military officers relied on an improvised pigeon post to communicate with each other during the Siege of Mutina. But this appears to have been an isolated incident. The Roman military did not routinely set up pigeon posts across the Republic or Empire. In spite of that, the Romans deserve credit for being the first to use pigeons in conflict.

Sources:

- Bennett, Charles E., Frontinus, The Stratagems and The Aqueducts of Rome, at XX (1925).

- Bostock, John, Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, BOOK X. THE NATURAL HISTORY OF BIRDS. Perseus. Retrieved October 26, 2022, from https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D10

- Chamberlain, Edgar, The Homing Pigeon, at 16, (1907).

- Kelley, Charles M., “Feathered Messengers in Heroic Role,” Machinists’ Monthly Journal, Vol. 43, No. 5, May 1931, at 285.

- Lewis, Sian, The Culture of Animals in Antiquity: A Sourcebook with Commentaries, (2018).

-

Pigeon Heroes of the Great War: Spike

Many of the famed war pigeons we’ve discussed at Pigeons of War were maimed in battle. This is not surprising, given that the birds served in active war zones. As visible targets flying over enemy lines, pigeons frequently lost legs, eyes, and wings. But some pigeons manage to remain injury-free in war. This week, we look at one such pigeon—Spike. Despite serving in dozens of missions during World War One, he allegedly was never injured.

Spike was born in France around 1917 or 1918 in a loft under the care of the United States Army Signal Corps. Of uncertain parentage, he possessed a grey “grizzle” coat and wasn’t much of a looker. But his trainers soon realized that this unattractive bird possessed myriad talents. “[H]e was a strong, aggressive, fast-flying bird with considerable vitality and unusual endurance,” an observer reflected after the War.

Having passed his training regimen with flying colors, Spike was assigned to service in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the fall of 1918. He wasn’t the only pigeon there—90 percent of the Signal Corps’ birds served in this campaign, which featured some of the bloodiest fighting in the War. Spike rode along in the Army’s tanks, flying important messages to the American HQ. He quickly set a record flight time of traveling 20 kilometers in 21 minutes. His speed, however, was the least of his abilities. In completing over 52 missions during the Meuse-Argonne campaign, Spike remained injury-free, despite flying through torrents of gunfire and artillery shells. Or at least that’s what the legend says. A newspaper account of Spike’s deeds published in the summer of 1919 claimed that he was gassed near Sedan, France on the day before the War ended.

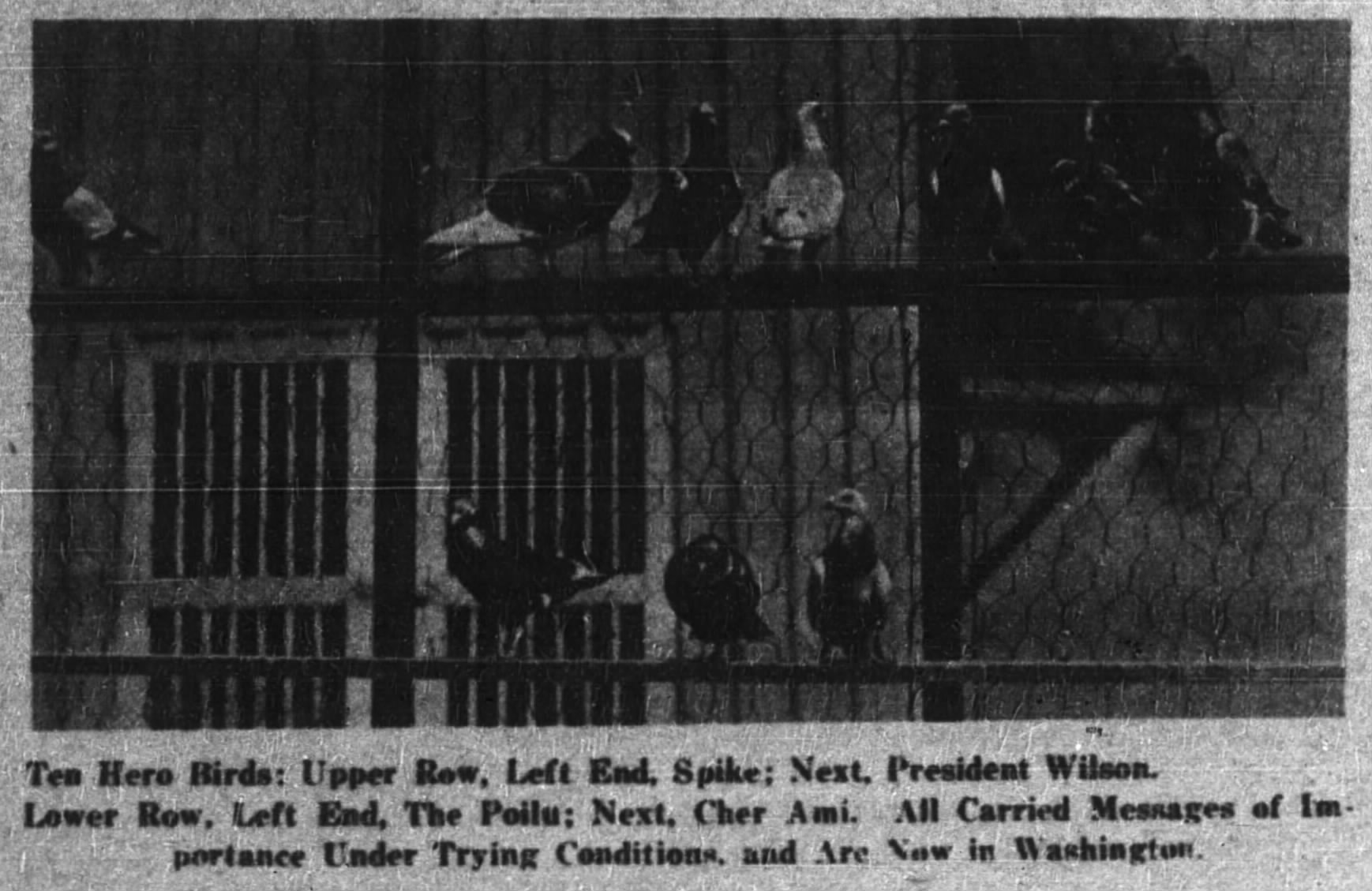

Whether Spike was injured or not, Army officials nonetheless credited the bird with stellar service. “This bird has probably rendered more efficient service than any other pigeon used in the war,” the Assistant Secretary of War wrote in Spike’s official wartime citation. Seeing an opportunity to create a public interest in the Army’s pigeons, General John J. Pershing issued an order requesting that Spike and other special war pigeons be sent to the United States for public exhibition. Spike boarded the troop transport ship Ohioan and arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey on April 16th, 1919. He was sent to a special Army loft for distinguished military pigeons in Potomac Park in Washington, D.C., where he joined President Wilson, Cher Ami, Mocker, and around 20 other pigeon war heroes. Open to the public, the loft allowed the pigeons to live a life of ease—food was provided and they were not expected to work, aside from daily flight exercises.

After a few years at the Potomac Park loft, Spike, President Wilson, and Mocker were sent to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, the headquarters of the Signal Corps’ pigeon program. The three of them were “kept in the cleanest, airiest of lofts” and “fed the choicest canary seed, rice and Canadian peas.” They also contributed to the Army’s breeding program by providing their superior genes. Indeed, one of Spike’s progeny, a pigeon named Sunnybrook, won several civilian pigeon races. Even in his later years, Spike remained feisty. In 1933, he picked a fight with Rheingold, a German pigeon captured during the War, over a nesting bowl in the central breeding and training lofts. Owing to the birds’ advanced ages, their trainer was able to break them up before the quarrel turned truly nasty.

After a lengthy retirement, Spike passed away on April 11, 1935. At 17, his death was attributed to natural causes. Thomas Ross, the Army’s resident pigeon keeper, noted the impact Spike’s passing would have on Mocker. “Oh, they were always scrapping, but Mocker, he’ll miss Spike.” His body was stuffed by a local taxidermist and sent to the office of the Chief Signal Officer in Washington, D.C for public display. These days, Spike can be viewed at the US Army’s Center of Military History.

Considering his heroism during the Great War, Spike should be as well known as Cher Ami. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. Unlike Cher Ami, there are no movies or books celebrating his wartime service. We at Pigeons of War feel this is a deplorable state of affairs–Spike was a hero and should be recognized as such.

Sources:

- Blazich, Frank A. “Feathers of Honor: U.S. Army Signal Corps Pigeon Service in World War I, 1917–1918.” Army History, No. 117 at 45-47.

- Bryant, H. E. C., “Pigeon Heroes to Be Honored,” The Charlotte Observer, Apr. 16, 1919, at 9.

- “Crippled Pigeon May Be Awarded D.S.C.,” The Evening Star, Apr. 17, 1919, at 2.

- “Death Whittles Ranks of War’s Pigeon Aces,” The Journal, Jul. 29, 1929, at 6.

- Doran, Dorothy, “Pigeons and People,” The Long Branch Daily Record, April 14, 1933, at 6.

- “Famed Army Pigeon Dead,” The Times-News, Apr. 13, 1935, at 6.

- Haskin, Frederic J., “The Pigeon’s Service,” The South Bend Tribune, July 26, 1919, at 10.

- “A Lone Survivor,” The Billings Gazette, May 1, 1935, at 4.

- Miller, James N, “The Passing of the Carrier Pigeon,” Popular Mechanics, Vol. 53, No. 2, Feb. 1930, at 194.

- “War Bird Heroes on Visit to City,” The Starry Cross, Vol. 28, No.4, April, 1919, at 92.

-

Pigeons in the Eighty Years’ War: The Siege of Zierikzee (1575-76 A.D.)

Last time we looked at the Eighty Years’ War, pigeons brought hope to the Dutch city of Leiden while it was under siege by the Spanish. But not all of the Dutch rebels’ attempts at using pigeons succeeded during that conflict. The city of Haarlem fell to the Spaniards in 1573 because they learned of a relief attempt from an intercepted pigeon. This week, we look at similar events that occurred during the Siege of Zierikzee.

The failure of the Siege of Leiden showed the Spanish that the Dutch rebellion would not easily be quashed. Bearing that in mind, Spanish authorities reluctantly agreed to hold a peace conference in Breda on March 3rd, 1575. But issues of religious freedom and greater autonomy for the rebellious provinces of Holland and Zeeland proved to be a sticking point. By July, the talks had broken down, prompting the Spanish government to renew its offensive against the rebels.

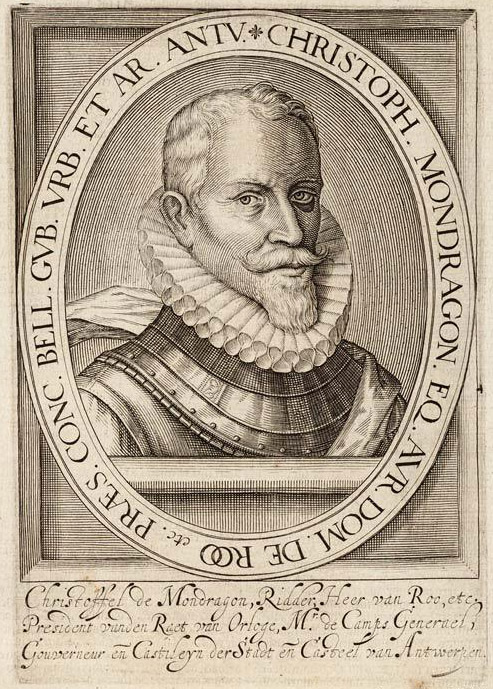

In the autumn of 1575, the Spanish forces launched a military campaign to wrest Zeeland from the rebels. Led by General Cristóbal de Mondragón, the troops invaded Duiveland Island. Meeting little resistance, most of the island quickly fell under Spanish control. They turned their attention westward to Schouwen Island. The most important town in that area, Zierikzee, was offered favorable terms for surrender by Mondragón in September. While the city’s council leaned toward accepting the offer, a letter from Prince William of Orange implored them to hold out for two or three months until he could bring reinforcements. Eventually, by the end of October, the town’s officials came around and rejected the surrender offer. Mondragón immediately surrounded Zierikzee with troops and artillery. The siege had begun.

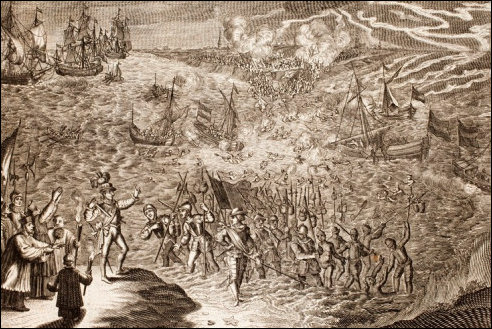

For seven months, Spanish forces assaulted the city. All roads to Zierikzee were closed off, making it impossible for the city to be supplied by land. The city could still be reached by its harbor at first, allowing the Prince to supply Zierikzee with provisions and weapons. A blockade of the harbor in January 1576, however, put an end to that. A rebel flotilla tried to break through in April. Although a few Spanish ships were captured and another was set aflame, the Spanish successfully pushed back the rebels’ ships. By May, the town had to impose rationing as provisions dwindled. To keep in touch with the Prince, inhabitants tried to smuggle pigeons to the rebel ships stationed near Walcheren Island. This was no easy feat—a smuggler had to swim past the Spanish ships surrounding the island and make it over the rebel ships. On April 21st, two men tied pigeons around their necks and swam toward the rebel ships, only to be caught by the Spanish.

In spite of the perils, several pigeons eventually were smuggled to the Prince. On May 18th, the Prince, along with Admiral Louis de Boisot—the hero of Leiden’s relief—prepared a message detailing their plan to attack the Spanish blockade with Boisot’s ships on May 27th. The note was tied to the bird’s leg and it was released. Unfortunately, the Spanish shot the pigeon as it was flying towards Zierikzee. Mondragón found the plans for the relief and sent them to his superiors, along with a feather from the bird. Thus, as Boisot’s ships reached Schouwen Island on May 27th, they encountered fierce resistance from the Spanish. Boisot’s flagship was sunk, killing him and many others. The remaining rebel ships quickly departed.

The Prince, never one to slink away from a challenge, sent another letter to Zierikzee via pigeon. He explained that he had 2000 “fine and skilled” Scottish soldiers ready to participate in a relief effort in mid-June. However, a Spanish musketeer shot this bird, too, as it flew toward the city. Aware that the Spanish government had possession of the Prince’s plans, the city finally threw in the towel and surrendered. On June 20th, city officials entered into negotiations with the Spanish, which concluded on July 29th. Spanish troops entered Zierikzee and took possession of the city, but, fortunately, the occupation was not long lasting. Fed up with a lack of pay, Spanish troops mutinied on July 12th. They squeezed the city’s inhabitants for money and goods, then abandoned the occupation on November 3rd.

The Siege of Zierikzee is a reminder that pigeons are not always a foolproof medium of communication. A bird can fail to deliver an important message, or, even worse, that message might be intercepted by hostile forces. These risks must be borne, however, in circumstances where suitable alternatives are not readily available.

Sources:

- De Zierikzeesche vrijheidsdag, at 44-45 (1872).

- Kanter, Johan de, Chronijk van Zierikzee, at 147 (1794).

- Swart, K.W., William of Orange and the Revolt of the Netherlands, 1572-84, (2003).

- van Riemsdijk, A. W. G., Secundum Fidem et Religionem: Philibert van Serooskerke (1537-1579) Een Zeeuw in dienst van de Spaanse koning. nvt (2021).

-

The Poilus: A Tale of Two War Pigeons

Many of the pigeons that participated in the Great War received names related to the conflict. The first American pigeon to deliver a message from the trenches was named Gunpowder, while British soldiers called one prominent bird Dreadnought. It should not come as a surprise, then, to learn that at least two pigeon heroes of the War were nicknamed the Poilu. A term of endearment for French infantrymen, the word literally means “The Hairy One,” a reference to the soldiers’ mustaches. In the case of the pigeons, however, the name seems to have alluded to their red-checkered coats, as the feathers resembled the traditional red trousers worn by the French soldiers.

The first Poilu achieved renown during the Battles of Yser and Aisne in the opening months of the War. Details about his service are lacking, but evidently it was impressive—Marshal Ferdinand Foch awarded the bird the Croix du Guerre. The citation for his award reads as follows:

On four occasions during the Yser and Aisne battles this carrier pigeon assured the rapid transport of important messages under heavy fire without error.

The Poilu lived until 1927. As a final honor, his body was stuffed and donated to the 8th Engineers Regiment, the Army unit responsible for France’s pigeons. The Regiment opted to display the Poilu in the hall of its headquarters in Montoire, France.

The second Poilu of fame was hatched in an American loft in France in the final year of the War. Like President Wilson, the Poilu first saw combat in mid-September 1918, when he was selected to accompany Lieutenant-Colonel George S. Patton’s Tank Battalions as they rode to the Saint-Mihiel salient. Carrying a total of 202 birds into action, the Tank Battalions lost only 24 of them in the process, mainly a result of inexperienced handling. By all accounts, the Poilu performed “splendid work” for the tanks, flying messages from the battlefield to American officials stationed at Ourches-sur-Meuse.As American troops withdrew from Saint-Mihiel, the Poilu was transferred to the Meuse-Argonne sector and assigned to the lofts at Cuisy. Before his training began, Captain Jack Carney, a Signal Corps officer who helped establish the American Pigeon Service, examined the Poilu and other birds in the loft. He reported the following exchange with the bird’s trainer in a post-war account:

‘Do you think he will go the route, Van Herwarden?,’ I asked the loft trainer.

‘I know it, sir. He went through St. Mihiel with the tanks. That’s the Poilu, sir. They don’t breed them any better. He’ll do all that’s asked of him, sir,’ was the quiet reply.

The trainer’s confidence in the bird was well placed. While out in the field on November 7th, an eagle-eyed officer spotted a German ammunition train and wanted to send word of this to HQ. Aware of his sterling reputation, he chose the Poilu for the task. As the bird flew back to Cuisy, he was hit by shrapnel multiple times, but kept flying. “With flesh and feathers on his head and neck hanging in ribbons, and reeling like a drunken man,” the Poilu landed in his loft with the message intact. The despatch was delivered to an artillery unit, which made short work of the ammunition train.

The Poilu received acclaim within the Signal Corps for achievements. Seeing an opportunity to create a public interest in the Army’s pigeons, General John J. Pershing issued an order requesting that the Poilu and other special war pigeons be sent to the United States for public exhibition. The Poilu boarded the troop transport ship Ohioan and arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey on April 16th, 1919. He was sent to a special Army loft for distinguished military pigeons in Potomac Park in Washington, D.C., where he joined President Wilson, Cher Ami, and around 20 other pigeons. Open to the public, the loft allowed the pigeons to live a life of ease—food was provided and they were not expected to work, aside from daily flight exercises. Not much information is available about the Poilu’s life afterwards. Presumably, he either was given away to a zoo or a private collector, or remained in the Signal Corps as a breeding bird.

The Poilu—the bearded French soldier, that is—was applauded in propaganda and war memorials for his bravery and endurance. We at Pigeons of War believe that those qualities were also present in the feathered Poilus.

Sources

- Blazich, Frank A. “Feathers of Honor: U.S. Army Signal Corps Pigeon Service in World War I, 1917–1918.” Army History, No. 117 at 45-47.

- Bryant, H. E. C., “Pigeon Heroes to Be Honored,” The Charlotte Observer, Apr. 16, 1919, at 9.

- Carney, Jack, “Story of Cher Ami’s Flight, Wounded, with Vital Message, Related by Captain Carney,” The Pittsburgh Daily Post, Apr. 27, 1919, at 1, 11.

- “Crippled Pigeon May Be Awarded D.S.C.,” The Evening Star, Apr. 17, 1919, at 2

- “France Honors War Pigeon,” The Springfield Leader and Press, May 30, 1927, at 9.

- Macalaster, Elizabeth, War Pigeons: Winged Couriers in the U.S. Military, 1878 – 1957, (2020).

- Naether, Carl A., The Book of the Racing Pigeon, at 59 (1944).

-

How to Sabotage Military Pigeons: A Primer

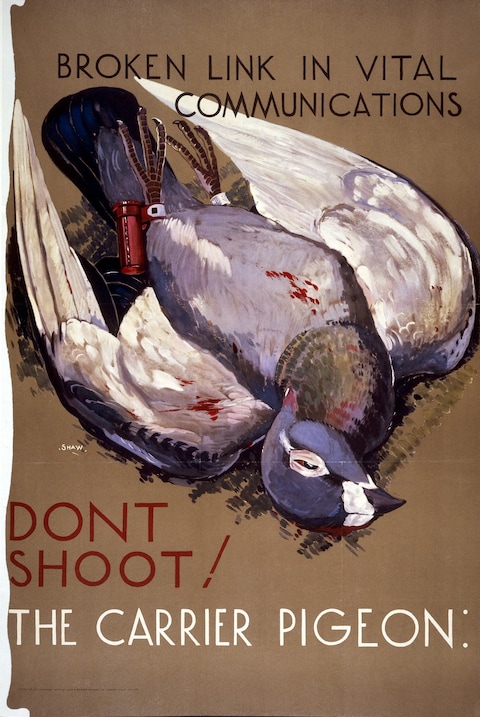

Since the Siege of Paris (1870-71), armies have tried to neutralize military pigeons. The reasons for this are easy to understand—pigeons allow the enemy to request aid and to receive confidential information from spies. To put a stop to these birds, militaries have recruited sharpshooters and hawks to dispatch them, or released intercepted pigeons with deceptive messages. This week, we examine these efforts in detail.

The most effective way to sabotage a military pigeon is perhaps the simplest—shooting the bird before it reaches its destination. Pigeons aren’t exactly hard to see—their bright patches of white or colored feathers and distinctive outlines make them easy targets. A shotgun is ideal for this purpose. Throughout the Great War, both the Allies and Germans were equipped with shotguns for shooting pigeons. Indeed, during the Battle of Verdun, the German Crown Prince Wilhelm formed a crack battalion of experienced trapshooters and equipped them with shotguns to shoot down any pigeons spotted flying to French HQ. During World War II, the Germans stationed marksmen along the northern French coast to shoot down pigeons flying toward Britain. In the leadup to the 1944 Invasion of Normandy, for instance, sharpshooters in Germany’s 352nd Division killed 27 Allied birds over two months.

But shooting pigeons mid-flight is not as easy as it seems, especially if the birds are released in groups. It also diverts soldiers from other duties and wastes ammunition. For these reasons, armies have experimented with training hawks and falcons to attack pigeons—a tactic that dates back to the Franco-Prussian War. When Prussian soldiers encircled Paris in 1870, the Parisians had collected some 800 pigeons from the north of France in advance of the siege, allowing them to send out information about the city to outer regions. Prussian troops released peregrine falcons to attack these pigeons as they flew from the city. To throw the falcons off, Parisians began releasing several pigeons “in rapid succession, each carrying a false note, until all of the enemy’s falcons were flying through the air in pursuit of one or more of the birds.” With a suitable distraction in place, a pigeon with an important message would be turned loose, escaping unscathed.

As armies eagerly added homers to their ranks during the Great War, rumors surfaced that the Germans had trained hawks and falcons to kill pigeons. By the Second World War, both the Allied and Axis Powers had incorporated birds of prey into their armies. The English Channel and North Sea were the scenes of most of these aerial battles. The Germans unleashed their falcons along the coast from Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, killing scores of pigeons. Likewise, the British, fearing German spies were using pigeons to contact their superiors, deployed falcons in the Channel Islands and coastal towns, but with much less success—a post-war report indicated that the British falcons hadn’t brought down a single enemy pigeon.

Birds of prey aren’t an entirely foolproof strategy—a hawk cannot be trained to distinguish between enemy and friendly pigeons. A soldier doesn’t have to kill a military pigeon to sabotage its mission, though. If the bird can be intercepted, one may insert a fake message into its message holder and release it. This technique has its roots in the Siege of Paris (1870-71). At one point during the siege, a French agent was caught traveling to Tours with Parisian pigeons. The Prussians took his six birds and released them with dubious messages. Parisian officials, nonetheless, saw through the ruse when the birds arrived “on account of the manner in which the messages were attached, and of the signatures appended.”

During both World Wars, both sides occasionally came across enemy pigeons, often when they captured soldiers or intelligence agents carrying them. While some of these birds were kept for breeding purposes (or eaten), others were roped into counterintelligence work. In the Great War, a British soldier who had been a medal maker learned to perfectly imitate the distinctive German message holders, which were “splendidly finished . . . with a red seal at the top.” Intercepted pigeons thereafter brought many dud messages back to the Germans. In his memoir on his unit’s experiences fighting the Germans in Italy in 1943-44, American pigeoneer Gordon Hayes reported that the Germans frequently attached to captured pigeons “a false message with a deceptive overlay map urging us to fire or bomb a certain location, seemingly the center of a heavy concentration of their troops and supplies. In fact, the false target would turn out to be a center of American troops or supplies.”

A special instance of counterintelligence involving pigeons emerged during the British campaign to airdrop homers into German-occupied territory to aid the resistance. It was hoped that members of the resistance would find these birds and send messages back to the British mainland. German forces, however, often found the birds. Sometimes the Germans attached a message requesting the names of resistance members or drops at suspicious locations. British intelligence sussed out many of these fake messages because the Germans tended to put too much military detail in them, revealing information that an average civilian would not know. Other times, the Germans swapped out the British bird with a German one, allowing for sensitive information to show up in German lofts. Aside from undermining British intelligence efforts, these acts also discouraged resistance members from participating—once word got out about this, the returns from British airdrops in the Netherlands dropped to zero for some time.

In lieu of counterintelligence work, there is a simpler option available for detained pigeons—a soldier can send a nasty message to the enemy. A steady barrage of demoralizing despatches can seriously damage the spirits of a platoon. And it doesn’t require much creativity or scheming. As recollected by Hayes, the 36th Infantry Division received the following dispiriting messages over a four-day period:

Monday, January 24, 1944

To the Americans

36th Division

Here is your pidgeon back. The German troops have enough meat to eat. By the way, we are gladly looking forward to your next visit by your degenerate lice-infested comrades.

(Signed) The German Troops

Tuesday, January 25, 1944

To the Americans

36th Division

We have your poor night patrolmen. Here is your pidgeon #2 back, so you will not have to starve. What do you want with your tin can tanks? Your imprisoned syphilitic comrades showed us the worth of the American soldier. We had to kill some of them before imprisonment. Right now your divisions south of Rome got hit. You sad nose-diggers.

(Signed) The German Troops

Friday, January 28, 1944

To the Americans

36th Division

Herewith we return a pidgeon to you. Your officers are too stupid to destroy important documents before being captured. At the present moment your division in the southern sector is getting a good hitting.

You poor fools.

(Signed) The German Troops

Hayes noted that his unit received similar messages throughout the War, but that they were too foul to print.

As the above demonstrates, there are abundant options available for compromising a military pigeon’s mission. Killing a pigeon prevents hostile forces from delivering vital information, while releasing a captured bird with erroneous information undermines intelligence gathering. The method utilized ultimately depends upon the needs and goals of the troops.

Sources:

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 113-114 (1888).

- Balkoski, Joseph, Beyond the Beachhead: The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy, at 78 (1989).

- Corera, Gordon, Operation Columba: The Secret Pigeon Service, 95-96, 106-106, 252-254 (2018).

- “Demobilization of War Pigeons,” The Decatur Daily Review, May 28, 1919, at 1.

- Gladstone, Hugh, Birds and the War, at 11-12 (1919).

- Hayes, Gordon H., The Pigeons That Went to War, at 66 (1981).

- “They Winged Their Way Through Skies of Steel,” The American Legion Weekly, Vol. 1, No. 9, Aug. 29, 1919, at 16-18.

- Walsh, George E, “Homing Pigeons,” The Southern Bivouac, Vol. 11, No. 1, June 1886 , at 187.

-

The Swedish Military’s Pigeon Service: 1886 – 1949 A.D.

A lot of ink has been spilled about military pigeons and their heroic actions during wartime. But what about those in peacetime armies? This blog is part of an occasional series examining military pigeon services in countries with strong traditions of neutrality. This week, we look at Sweden’s former military pigeon service.

Like most European countries, Sweden’s use of military pigeons dates back to the latter-half of the 19th Century. In the fall of 1886, the Swedish Army decided to establish a pigeon service at the Karlsborg Fortress. Situated on the Vanäs peninsula by lake Vättern, the Fortress was built to realize the Army’s central defense idea, a concept in vogue following the Finnish and Napoleonic Wars. In the event of war, the King and his government would retreat to the secluded Fortress to carry out their official functions. A pigeon service was highly desirable under these circumstances, as it would allow the government to communicate with the surrounding terrain without the need for telegraph lines.

Lieutenant Berggren, an officer in the Royal Fortifications Corps, was tasked with setting up the loft at Karlsborg. He traveled to Copenhagen, Denmark to brush up on his pigeon knowledge. While there, he purchased several hundred birds from a wholesaler. Once the loft was established, Berggren turned over day-to-day management to an engineering unit.

To ensure reliable service over a wide expanse, soldiers focused on training the pigeons to fly from specific areas—Örebro in the north, Bråviken in the southwest, and Tibro and Stenstorp in the southeast. Impressive results were obtained when conditions were optimal. At Bråviken, the birds flew 84 miles (135 km) within 2.5 hours. In Tibro—around 17 miles (27 km) away from the Fortress—the pigeons arrived back at their loft within 15 minutes. However, a release at Stenstorp during wind and rain resulted in the pigeons not returning until days later. Hawks also preyed on the flocks from time-to-time. At some point in the 1890s, the loft was discontinued.

The military did not consider using pigeons again until 1909, when a special committee proposed that a “balloon and pigeon department” be established at the Boden Fortress. Presumably, the pigeons would’ve allowed the balloon pilots to communicate with their home base while in flight. However, it doesn appear that this suggestion was ever acted upon, as it wasn’t until the 1920s that the Swedish military re-established its pigeon service. Inspired by the success of other countries’ pigeon services during the Great War, the country’s navy experimented with pigeons at its air station in Rindön and at the Gothenburg naval depot, seeking to use the birds in lieu of radio for reporting accidents or observations. The Army, too, brought back its pigeons, setting up lofts at Boden and Stockholm and experimenting with mobile coops stationed throughout the country. The Army also worked toward developing a breed of pigeon acclimatized to the climate in Upper Norrland, the country’s northernmost region.

Aware of increasing international tensions, in 1936 the Swedish government increased the budget for its military. One result of this was that the Army reorganized its pigeon service, placing it under the Signal Troop’s control. With Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1st, 1939, Sweden officially declared its neutrality. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union’s invasion of Finland on November 30th, followed by Germany’s invasion of Denmark on April 9th, 1940, prompted the government to implement general mobilization. From 1939 to 1945, around 1 million Swedish conscripts were drafted for military service.

During this period of military preparedness, the Signal Troop’s pigeon service was fully involved in Army operations. A summary of the service’s activities during this time can be found in the memoir of Per Gunnar Bengtson, who was drafted into the pigeon service in 1939. In April 1940, fearing a German invasion from the south, the Army moved most of its pigeons and mobile coops to Skåne County. While there, Bengtson trained his birds to make flights from the County’s coasts. As the threat of invasion dissipated, pigeon units—including Bengtson’s—were then sent to other parts within the country, such as Västra Götaland County. The units trained their birds for scouting and reconnaissance missions, as radio communications were not well developed at that time. That winter, military officials encouraged the pigeon units to conduct cold weather experiments to see if using pigeons in winter conditions was possible. In one experiment involving 30 of Bengtson’s pigeons, only 4 were lost over 21 winter flights. Although many of these pigeons did not return to their lofts in a timely fashion, these results were nonetheless encouraging, given that some flights had occurred during

In the spring of 1941, Bengtson’s unit and several others were sent to Dalarna County near Norway and directed to train their birds to make flights from the border. In spite of vast forests and abundant birds of prey, Bengtson’s pigeons obtained some of their best results in this area. Cooperation with the local infantry units was also excellent—the pigeons were sent to posts at various defense lines and even participated in a larger battalion exercise. Good results were also achieved in Jämtland County that summer, though pigeon losses were greater owing to the mountainous terrain. By spring 1943, Bengtson’s unit found itself in Värmland County, but further from the border. Training now focused on longer flights. Because of a lack of gasoline, all of the pigeons now had to be transported to training sites via bicycle. In spite of these challenges, Bengtson’s unit did not lose a single bird in this period. Shortly thereafter, Bengtson’s unit was demobilized, as the Army wound down its affairs once it became apparent Germany no longer posed a threat to Sweden.

In spite of promising results attained during Sweden’s military preparedness campaign, the Army’s pigeon service would not be around for much longer. In 1948, Army officials recommended that the service be disbanded as a cost-cutting measure. Rather than using their own birds, officials proposed that the Army could rely on civilian fanciers to supply pigeons, if the need arose. To support this endeavor, they also suggested that the state issue annual grants of 7,000 krona to the Swedish Carrier Pigeon Association—this amount would support the group’s activities and entice members living near strategic military sites to supply pigeons to the Army as needed. The government adopted the Army’s recommendation and the pigeon service was officially dissolved in 1949.

Sweden’s military pigeon service forms an interesting chapter in the country’s military history. Although the birds were never tested in combat, they improved communications within the Swedish military when reliable radio service was lacking. We at Pigeons of War think that is worthy of praise.

Sources:

- Angående Statsverkets Tillstånd Och Behov Underbudgetåret 1928/1929, available at https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/proposition/angaende-statsverkets-tillstand-och-behov_DP301b1

- Ballonghallen. Fortifikationsverket.. Retrieved September 8, 2022, from https://www.fortifikationsverket.se/fastighetsforvaltning/fastighetsbestand/byggnader/1910-1930-talet/ballonghallen/

- Bengtson, Per Gunnar, Brevduvan i Militär Tjänst, (1984)

- Betänkande och förslag rörande revision av Sveriges försvarsväsende – Del 2 – Sjöförsvaret – Sammanfattning av revisionens förslag – Särskilda yttranden, at 20 (1923).

- Kungl. Maj:ts proposition nr 206, available at https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/proposition/kungl-majts-proposition-nr-206_E930206b1/html

- Rundgren, K. G., Brevduvan. En kulturhistorisk studie, at 123 (1991), available at https://www.postmuseum.se/bocker/1991/1991_9-111-126_Rundgren.pdf

- Högman, H, Animals in War Service. Military. Retrieved September 7, 2022, from http://www.hhogman.se/animals-in-war-service.htm

- Högman, H, Sweden’s Military Preparedness 1939 – 1945. Military. Retrieved September 8, 2022, from http://www.hhogman.se/infantry-swe-1939-1945.htm

-

Pigeons in the Eighty Years’ War: The Siege of Leiden (1574-75 A.D.)

A European city encircled by enemy forces. The inhabitants—cut off from food and communication with the outside world for months—recruit pigeons to fly messages into the city.

Sound familiar? Readers of this blog will undoubtedly be reminded of the 1870-71 Siege of Paris, but this scenario has happened several times in European history. This week, we take a look at how pigeons brought relief to the Dutch city of Leiden in 1574 during the Eighty Years’ War.

In the latter-half of the 16th century, the Dutch populations of the Habsburg Netherlands began rebelling against the reign of King Philip II of Spain, motivated by myriad issues. Led by the charismatic William the Silent, Prince of Orange, many of the cities in Holland and Zeeland revolted, with the city of Leiden joining the fight in 1572. Spanish forces tried to retake these wayward cities via siege warfare, but achieved mixed results. Haarlem fell to the Spanish in July 1573, while Alkmaar repulsed a siege attempt in October. That same month, Spanish General Francisco de Valdés launched a siege against Leiden. The blockade lasted until April 1574, with the Spanish making no progress against the city’s defenses. The siege was halted while de Valdés squared off against invading rebel troops.

On May 26, 1574, de Valdés and his troops returned to Leiden, setting up sixty-two fortified positions blocking every road in and out of the city. The Prince of Orange circulated a letter to the city officials, pleading with them to hold off for at least three months; he needed time to cut the nearby dikes and let the North Sea flood the area, allowing the rebel flotilla to sail in with reinforcements and provisions. Residents buckled down for a tough summer.

Although the siege had been halted for a few weeks, the city had failed to replenish its food stores—there was only enough to last for two months. By August, the bread had run out. Desperation set in—the inhabitants ate anything and everything they could get their hands on, including dogs, cats, and rats. Beer, too, was in short supply, forcing people to drink foul canal water. To make matters worse, plague and dysentery swept across the area. A total of 6,000 citizens died, nearly half of the city’s 15,000 population.

As August gave way to September, the situation seemed utterly hopeless. Beaten down by hunger and disease, many townspeople felt the time had come to surrender to the Spanish, knowing full well there was a chance that the troops might slaughter everyone in the city. On September 8th, a riotous crowd gathered outside of the town hall to demand Leiden’s surrender. In a dramatic gesture, Mayor Pieter Adriaansz van der Werf announced to the group that the city would never surrender and allegedly offered to let the starving population eat his body. Inspired by his noble offer, the crowd dropped their demands and dispersed.

But symbolic acts would only keep Leideners mollified for so long. City officials needed to get in touch with military leaders to find out if aid was forthcoming. Couriers were not an option, as it had grown too dangerous for them to travel back-and-forth through the enemy lines. Officials considered the possibility of using pigeons. During the Siege of Haarlem, the city had used them to communicate with the Prince of Orange. A pigeon post was not without its hazards, however. Indeed, one of the birds sent by the Prince to Haarlem had fallen into the enemy’s hands, revealing his plans to the Spanish. Alerted to this new medium, Spanish soldiers thereafter shot every single bird that flew over their camps. Officials also wondered if there were even any pigeons left in a city wracked by starvation.

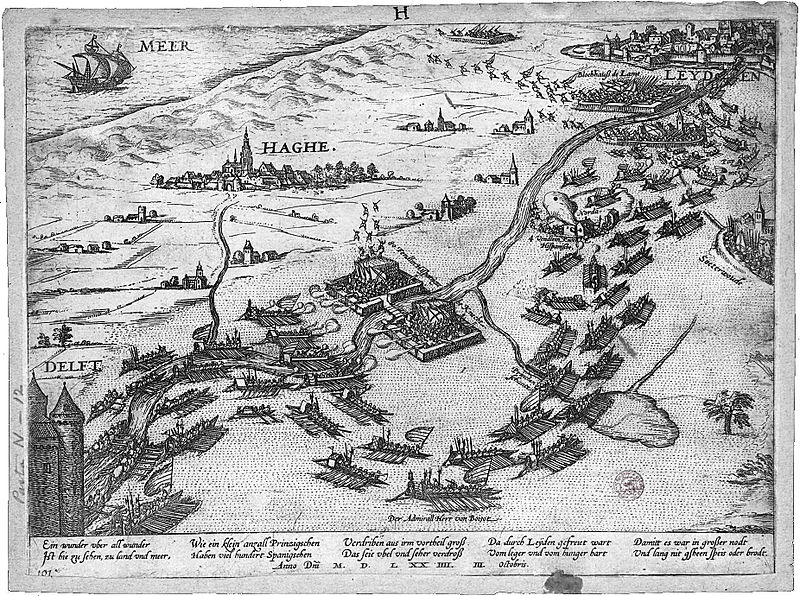

Thankfully, Willem Cornelisz. Speelman, a church organist, stepped up to the plate. Somehow, Speelman and his brothers had kept eight pigeons alive during the famine—a remarkable testament to their willpower. Speelman turned the birds over to city officials, who arranged for them to be smuggled past the Spanish camps. On September 26th, two men from Leiden reached the rebel fleet and told them about their dire circumstances. They handed the pigeons over to Louis de Bosiot, the commander of the fleet, who wrote two letters detailing his progress—he assured city officials that his ships would sail into Leiden as soon as the waters were high enough to pass through the now-broken dikes.

On September 28th and 29th, two of Speelman’s pigeons returned bearing de Boisot’s messages. The letters were read in public and bells were rung. Leideners rejoiced at the news that relief was imminent. They didn’t have to wait much longer. On October 1st, a major storm caused the North Sea to flow through the broken dikes, flooding the land near Leiden. Fearing the incoming floods, de Valdés and his soldiers hurriedly abandoned the siege on October 2nd. The next day, the rebel fleet arrived at Leiden, distributing bread and herring to the city’s population. The city had been saved from the brink of destruction.

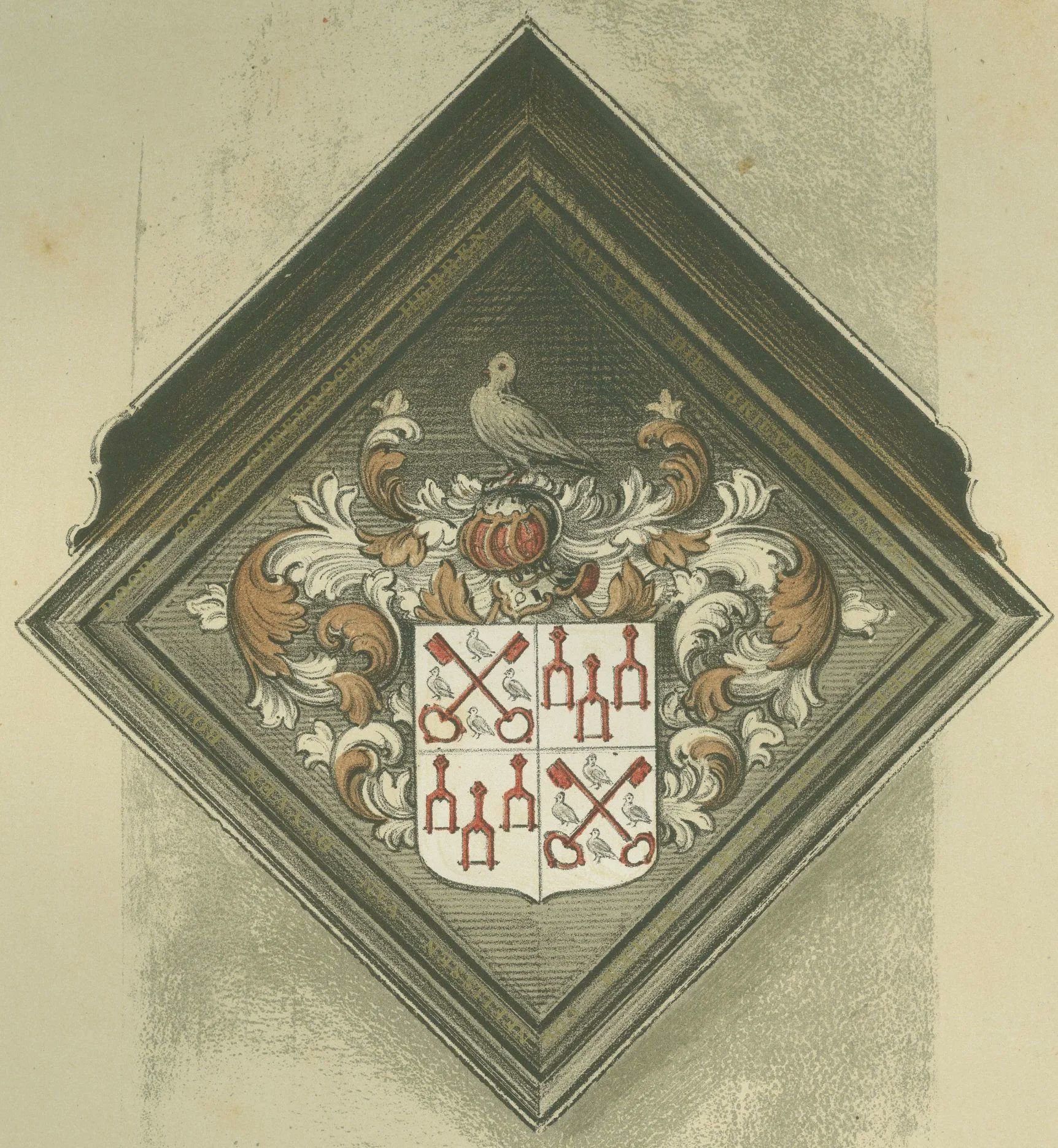

Thanks to his efforts, Speelman became a town hero. His pigeons had brought assurances to Leideners that help was on the way. Had this news not arrived, Leiden might have surrendered, dissuading other cities from revolting. Speelman received a gold medal in 1578 in recognition of his contributions as well as the honorific surname Van Duivenbode (the Pigeon Messenger). His family also received the right to bear a coat of arms featuring two red keys of the city and a blue dove in each of the four quadrants—a privilege rarely accorded to non-nobility.

The pigeons, as the bearers of good tidings, were likewise lauded for their efforts. The city paid for their food for the remainder of their lives. After they died, they were stuffed and mounted for display in Leiden’s town hall. A popular exhibit for several centuries, the pigeons were eventually lost to the ravages of time. The letters they carried from de Boisot have survived—they can be seen at the Museum de Lakenhal.

Each year, Leiden commemorates its salvation with lavish celebrations on October 3rd. Residents eat bread and herring while participating in parades, historical reenactments, and memorial services. We at Pigeons of War plan on raising a glass that day to Speelman and his pigeons, who brought Leideners hope when it was most needed.

Sources:

- Albert, Marvin H., Broadsides & Boarders, at 25 (1957).

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 112 (1888).

- Clarke, Carter W. “Signal Corps Pigeons.” The Military Engineer, vol. 25, no. 140, 1933, pp. 133–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44563742. Accessed 30 Aug. 2022.

- Ekkert, R.E.O, Jaarboekje 1974 voor geschiedenis en oudheidkunde van Leiden en omstreken, at 11, 197-215 (1974).

- Joel, Lucas. “Benchmarks: October 2, 1574: Dutch Unleash the Ocean as a Weapon of War.” Earth: The Science Behind the Headlines, 20 Sept. 2016, https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/benchmarks-october-2-1574-dutch-unleash-ocean-weapon-war/.

- Koppenol, Johan, “Noah’s Ark Disembarked in Holland: Animals in Dutch Poetry, 1500-1700,” Early Modern Zoology, Vol. I, at 478 (2007).

- Mackeson, Charles, “Sketches of Travel in Holland,” The Churchman’s Shilling Magazine and Family Treasury, Vol. XXX, Sept. 1881 – Feb. 1882, at 520.

- “Siege and Relief of Leiden.” Museum De Lakenhal, https://www.lakenhal.nl/en/story/siege-and-relief-of-leiden-oud.

-

Pigeons in the Iraq War: Interview with Stacy Jeambert, former Chief Warrant Officer for the 1st Marine Division

Several weeks ago, we wrote about how the 1st Marine Division used pigeons for chemical detection in the first months of the Iraq War. A rare instance of pigeons being used in modern warfare, the article has become the most popular one featured on this blog. To shed more light on this fascinating story, we reached out to former Chief Warrant Officer Stacy Jeambert for further information. As the 1st Division’s Nuclear, Biological, and Chemical officer, Mr. Jeambert was the lead advocate for using pigeons as a Sentinel Species in the leadup to the invasion of Iraq. Mr. Jeambert graciously agreed to an interview, which is reproduced below—a Pigeons of War exclusive. His responses have been lightly edited for clarity.

Q: How did you decide to select pigeons as a Sentinel Species?

A: Initially, we purchased chickens—I did this previously during Desert Storm; however, the chickens, which had been previously housed in warm chicken houses, died from exposure to the elements. As the team and I discussed what to do next, we settled on the pigeon, as they are very hardy and are used to the weather.

Q: Did you get any pushback from superiors or colleagues?

A: We received tremendous pushback from the Pentagon, specifically from General Reeves’ office. [Editor’s note: Major General (ret.) Stephen V. Reeves was the Joint Program Executive Officer for Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Defense for the Department of Defense during this period.]

When all the chickens died, it was a huge embarrassment for the 1st Marine Division in the press. Colonel John Kelly—when I approached him about buying the pigeons—said no. [Editor’s note: At the time a Colonel serving with the 1st Division as assistant division commander, John Kelly shortly thereafter was promoted to Brigadier General. He most recently served as President Donald Trump’s Chief of Staff from 2017 to 2018]

I persisted and stated that if it was a good idea before, bad press should not make it a bad idea now. He agreed and told me to write a rebuttal for the press that I would give to the Public Affairs Office. I did, he [then] agreed, and we purchased, I believe, 220 pigeons.

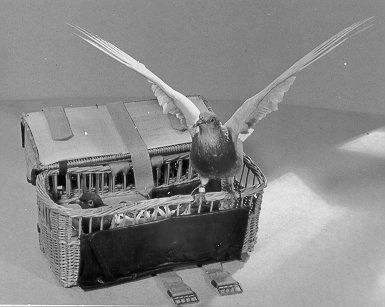

Q: How were the pigeons distributed within the 1st Division?

A: There was no real rhyme or reason as to how the pigeons were distributed—units asked for a certain amount, and we provided. We provided cages that were purpose built to be strapped on top of the Humvees and gave the units plenty of food for the birds.

Q: Were they assigned to specific individuals within the units?

A: Yes, the units did assign a Marine(s) to take care of the birds.

Q: How were the pigeons transported during operations? Did they ride on Humvees or other motorized vehicles? (one article published at the time said that wasn’t a good idea because the vibrations would disturb the birds)

A: I have no idea about the vibrations disturbing the birds, but yes, we did transport them that way—either strapped to the Humvee in the cage or [placed] inside the vehicle. It should be noted that these convoys moved very slowly; the roads into Iraq were packed during the invasion.

Q: Did any of the pigeons appear to suffer from a chemical attack?

A: No—we never lost any, either. Those pigeons were well taken care of by the Marines in charge of them and did very well.

Q: After initial operations ended, what happened to the pigeons? Were they sold off, given away, or simply let go?

A: We let them out of their cages, but they kept coming back. When we had Marines go up to Tikrit, once they were on their way back, they released the birds, but they followed the trucks and would land inside them—all the way down to our staging areas in southern Iraq.

Q: Any funny or interesting stories you care to share about the pigeons?

A: One of the Marines in the 1st Marine Regiment had the cage open and was petting the bird when it just flew off. It perched itself on top of one of the communications antennas close by. I received a call, asking for a replacement—I said sure. Later that same day, when it started getting dark, the pigeon flew back down and got in its cage—we all thought this odd.

A few days later, I was walking to the chow tent, and I see the 1st Marine Division Comptroller coming toward me, yelling my name and waving a piece of paper; it was the invoice for all these pigeons. On the invoice was the description—we had purchased trained homing pigeons. I did not purchase these pigeons, I sent my Staff Sergeant, with a few Special Forces soldiers, into Kuwait City to buy these things—she had no idea, but that’s what she bought ($60 per bird).

-

August De Corte: How Uncle Sam Stiffed An Innovative Pigeoneer During World War One

A declaration of war is often accompanied by economic opportunities. Governments invest heavily in industry to meet demand and fortune often follows those lucky enough to get a contract. But not in every case. Today, we discuss the plight of August De Corte, a pigeon fancier-cum-inventor who advised the United States Army Signal Corps during World War One. Despite supplying the Corps with pigeons and developing wartime equipment, De Corte ultimately was left impoverished after the War.

Born in Belgium in 1862, August De Corte immigrated to the United States in 1897. A interior decorator by trade, De Corte set up shop in Staten Island, New York. Yet his true passion was breeding Belgian homers and Groenendaels, long-haired, black varieties of the Belgian Shepherd breed. Indeed, he’d brought his dogs and pigeons along with him when he immigrated to the US. For over 20 years, he operated a dog and pigeon farm, becoming a pioneer in the breeding of Groenendaels in America. He also was a regular fixture at dog and bird shows during this time.

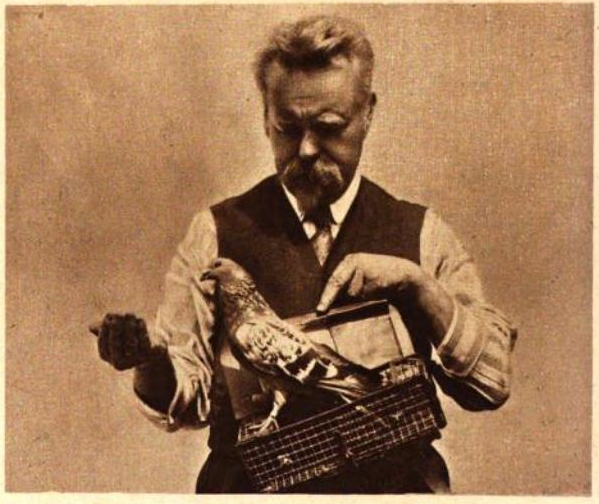

As a native of Belgium, De Corte undoubtedly kept a close eye on the Great War as it raged across Europe. Accounts of pigeons being used for emergency communication services must’ve intrigued him, given his background as a pigeon fancier. When the US seemed poised to join the conflict at the start of 1917, De Corte sprang into action. According to an affidavit he authored in 1920, De Corte met with Signal Corps officials in New York on February 6, 1917 to give them an in-person demonstration involving a mated pair of Belgian homers, Uncle Sam and Victory. “I proved why pigeons were needed at once by the government for communication work,” he testified, “and how by my patents and methods they could be made immediately available.”

Based on this demonstration, De Corte entered into an advisory relationship with the Signal Corps, meeting and consulting with officers and other civilian advisors throughout 1917 and 1918. De Corte would claim in his 1920 affidavit that he tendered 14 of Uncle Sam and Victory’s offspring to the Signal Corps on April 9th, “two weeks before any other pigeons were used by the War Department.” Another 14 were supplied that same month, six of which “were the first pigeons sent to France to be used by the American Expeditionary Forces.”

Aside from supplying pigeons, De Corte worked toward devising better equipment for the Army’s homers. Many of these devices were for use by soldiers out on scouting or reconnaissance missions—an ideal scenario for using carrier pigeons. He claimed no fewer than five inventions during this period, each of which is described below:

Wire Cage

A special, light-weight wire cage was designed for soldiers to carry pigeons while out in the field. It was just large enough to hold one bird securely and comfortably—the bird could stick its head out, but couldn’t fly away. Because the cage was made out of wire, the bird could be fed and a message inserted in its holder without it having to be released.

A leather strap allowed for the cage to be fastened to a button on a soldier’s uniform, permitting it to be worn on the chest or back. A reporter for Scientific American, who personally attached the cage to his vest, noted that it “would offer no appreciable impediment to marching or, within moderation, even to fighting.” The cage could also be strapped to a dog in case human couriers were unavailable—De Corte’s Groenendaels happily served as models in a series of photographs.

A leather cover folded over the top of the cage to protect the pigeon from the elements. The inside of the cover had room for pencils, paper, and grain. The cover also served as a writing table.

Parachute & Balloon

These two inventions—both of which were intended to be attached to the wire cage—were for sending pigeons to soldiers separated from their main units. If their exact positions were unknown, an aviator could use the parachute to airdrop the pigeons over their approximate area. If their positions were known, pigeons could be sent to them via the balloon, assuming a favorable wind was blowing in that direction.

Message Holder

De Corte created a new type of holster for attaching messages to a pigeon’s body. The device consisted of a rubber tube attached to a leather harness. The harness slid over the pigeon’s neck, under its wings, and around its legs, making it nearly impossible to be seen. Meanwhile, the tube hung low near the pigeon’s feet—this was to allow the tail feathers and wings to camouflage the tube when the bird was in flight. In De Corte’s opinion, this message holder would make it difficult for enemy troops to spot Army pigeons.

Portable Loft

De Corte developed a portable pigeon loft for mobile operations on the battlefield. It had four wheels, allowing it to be towed by trucks. The interior could house 75 pigeons along with sufficient quantities of food and water. The loft was configured so that a returning bird’s entry would trigger a bell. Once inside the coop, the pigeon was trapped in an interior compartment until it was retrieved. A photograph taken in late-1918 shows that it could be disguised effectively with camouflage to blend into its surroundings. Evidently proud of this invention, De Corte applied for a patent in May 1918.

With the War over, De Corte presented a claim to the War Department in June 1919 for his services. After all, he’d helped the Pigeon Service immensely by supplying birds and designing wartime equipment. “My birds, at the front in the war, by their efficiency and helpfulness were the means of saving thousands of American lives,” he boasted. Meanwhile, his interior decorating business had suffered, given his sole focus on assisting the Signal Corps. The War Department saw things differently, however. It claimed that De Corte knew from the outset that no civilian would receive any compensation for services rendered. The Army’s Judge Advocate General Office agreed with the agency’s position, holding that “[s]ervices rendered gratuitously and accepted on that premise can not thereafter be made the basis of a legal claim for compensation.”

The War Department’s refusal to pay was a terrible blow for De Corte. With his business in shambles, De Corte was now penniless and nearing sixty. “[B]roken in spirit and disappointed because of lack of recognition by the government,” he prepared to sail to Belgium on January 21st, 1920, to spend the rest of his life there. Before leaving, however, he handed off Uncle Sam and Victory—the parents of the first birds in the Pigeon Service—to his representative for display at the upcoming annual Madison Square Garden exhibition. A set of instructions he left for the representative gives us a glimpse into his generalized depression: “Kill my birds after the show and send the bodies to the Museum of Natural History to be mounted and preserved as historic birds.” A wave of outrage swept the fancier world when this leaked out—this was no way to treat the founding birds of the Pigeon Service. The pair were instead auctioned off, with the proceeds going to De Corte.

De Corte returned to Belgium and was never heard from again. It’s a shame that his story ended so tragically. While the War Department was correct from a legal standpoint, it arguably had a moral obligation to pay the man for his services in light of the sacrifices he’d made. Without his assistance, the Signal Corps’ Pigeon Service might never have gotten off the ground. We at Pigeons of War salute De Corte for his achievements.

Sources:

- De Corte, August, “What I’ve Learned From Dogs About Human Nature,” The American Magazine, Vol. 87, Jan. – Jun. 1919, at 60.

- Lamar, Nelson, “Saving Soldiers With Pigeons,” The Wilmington Morning Star, Feb. 11, 1919, at 10.

- “Splendid Exhibit of Poultry,” The New York Herald, Jan. 19, 1919, at 45.

- “The Pigeon Express,” Scientific American, Vol. 119 No. 14, October 5, 1918, at 271.

- “Two Army Pigeons Insured for $5,000,” New York Daily Herald, Jan. 19, 1920, at 20.

- “Victory Near End, So Is Uncle Sam,” New York Daily Herald, Jan. 23, 1920, at 18.

- War Department, Opinions of the Judge Advocate General of the Army, January 1919, at 911-912 (1919).

Home