-

Old Anchor: A Naval Pigeon That Jumped Ship During World War One

In the final months of the Great War, the German Army frequently left behind their pigeons as they beat a hasty retreat from encroaching Allied forces. Many of these abandoned birds, as we’ve previously written about, were eagerly adopted by the Americans, who incorporated them into breeding programs back stateside. But Germany’s Army was not the only branch to have its own pigeons. Indeed, the German Navy’s pigeon program dated back to the 1880s. Did any of its birds become POWs? This week, we’ll take a look at a German naval pigeon that jumped ship while American vessels were laying down mines in the North Sea.

On April 6th 1917, the United States officially declared war on Germany. The US entered the fray at a crucial juncture—German U-boats were attacking merchant ships at a merciless rate. That month alone, submarines sank approximately 800,000 tons worth of ships bound for French and British ports. If this rate continued unabated, Allied officials feared that the Central Powers would attain victory within a year, as the diminished Allied merchant fleet would not be able to supply the necessary materiel needed to win the War.

The US Navy realized that these increasing submarine attacks meant that troop transport ships carrying American soldiers and supplies to the Western Front were liable to be sunk. As early as April 15th, naval planners circulated a memorandum exploring the possibility of installing mines in the North Sea. The British Navy had previously placed mines in the English Channel, which had caused the U-boats to head north around Scotland. A barrage placed across the North Sea ideally would close this alternative route, thereby preventing U-boats from traveling to Atlantic shipping lanes. After some internal debate, US naval officials discussed the proposal at the Allied Naval Conference in September 1917, where the British Admiralty expressed support. By November 1917, both country’s governments had signed off on what became known as the North Sea Mine Barrage.

As envisioned, the plan called for the following objective:

A barrier of high explosives across the North Sea – 10,000 tons of TNT -, 150 shiploads of it, spread across an area 230 miles long by 25 miles wide and reaching from near the surface to 240 feet below – 70,000 anchored mines each containing 300 pounds of explosive, sensitive to a touch, barring the passage of German submarines between the Orkneys and Norway.

The first US naval ships arrived off the coast of Scotland in May 1918. In June, the British and American navies set to work laying mines in agreed upon zones. The American minelaying fleet consisted of aging protected cruisers and former commercial steamships. British destroyers accompanied them as they worked, providing cover via smokescreen to conceal the ships’ activities.

The fleet labored all summer, laying dozens of miles of mines at a time. One day, amidst a fierce gale, the sailors spotted a red-checkered pigeon fluttering wearily up in the sky. It landed on the deck of one of the ships, exhausted and beaten down from the wind and rain. Crew members noticed that the pigeon’s leg band bore a code indicating it belonged to the Germany Navy, which had several pigeon stations along the North Sea. It was a young bird, having hatched earlier that year. At under a year old, the pigeon likely was lost in a training exercise, but maybe it had intentionally defected, fed up with life at sea. Regardless of its motivation, the pigeon was now a POW—when the ship returned to port, the pigeon was promptly handed over to the US Army Signal Corps.

After five months of work, the American and British minelayers finished the barrage at the end of October 1918. The War ended a few weeks later. A total of around eight U-boats sank thanks to the North Sea Mine Barrage. Attention now shifted to minesweeping, which took most of 1919.

Meanwhile, the Signal Corps decided that the pigeon—now christened Old Anchor—would be used in an experimental breeding program at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. Old Anchor headed to his new home in 1919, placed under the care of Thomas Ross, the Fort’s pigeon expert. As he took to his surroundings, Old Anchor proved to be quite the lothario. He fathered many of the Fort’s best-performing pigeons over the years. From 1928 through 1933, many of his sons and daughters regularly won 600- and 700-mile races. One descendant—named General George S. Gibbs, in honor of the Signal Corps’ then-commander—won the gold cup for best bird in America at a pigeon show held in New York City in 1929. At another New York show in January 1934, 20 of Old Anchor’s descendants won a total of fourteen first prizes, four seconds, and two thirds in addition to five trophy cups.

Old Anchor became a long-term resident at Fort Monmouth, seeing his 21st birthday in 1939. But that same year, various old age ailments started catching up with him. He lingered for a few months, then passed away on April 5th, 1939. A beloved figure at this point, no excess was spared for his interment. Personnel at the Fort constructed a special wooden casket and a military funeral with full honors was held for him, including a 21-gun salute. It was a fitting tribute to a pigeon who had greatly improved the quality of the Army’s birds.

Sources:

- Belknap, Reginald, The Yankee Mining Squadron, at 17 (1920).

- “German Pigeon Dies at Fort Monmouth,” The Daily Record, Apr. 6, 1939, at 1.

- The US Navy Department, The Northern Barrage and Other Mining Activities, (1920).

- “Two Veterans Pass,” United States Army Recruiting News, August 1939, Vol. XXI, No. 8, at 7.

-

Braddock: The Newspaper Pigeon Who Joined The Army

At Pigeons of War, we’ve devoted several articles to famous war pigeons. We’ve written about Gustav and President Wilson, for instance, both of whom spent their formative years in the military. However, thousands of pigeons from all walks of life were donated to the military during both World Wars. This week, we take a look at a newspaper pigeon’s accomplishments before he was drafted for service in World War II.

In the 1930s, photojournalism—the process of telling news stories through images—emerged as a popular trend in the print media world. Eager to meet their audiences’ appetites, newspapers looked for ways to get pictures from their photographers as quickly as possible for immediate circulation. Portable wirephoto equipment, which would allow for the instantaneous transmission of pictures over phone lines, was bulky and impracticable at this point. Meanwhile, in highly urbanized metro areas, cars, bicycles, and human couriers faced the obstacle of traffic congestion. A delay of even just a few minutes might result in a rival paper printing photos from the same news story.

For these reasons, several New York-based newspapers and photographic agencies actively maintained flocks of pigeons throughout the decade. These birds—cross-breeds of Army pigeons from Fort Monmouth, New Jersey (NJ) and prize-winning racing homers—transported photographic negatives from photojournalists out in the field to the newspapers’ offices. The pigeons regularly accompanied reporters assigned to ship arrivals, murder cases, sports games, natural disasters, and run-of-the-mill news stories. Most of these assignments were within 30 or 40 miles of the newspapers’ lofts, but could extend to over 100 miles away, depending upon the needs of the story.

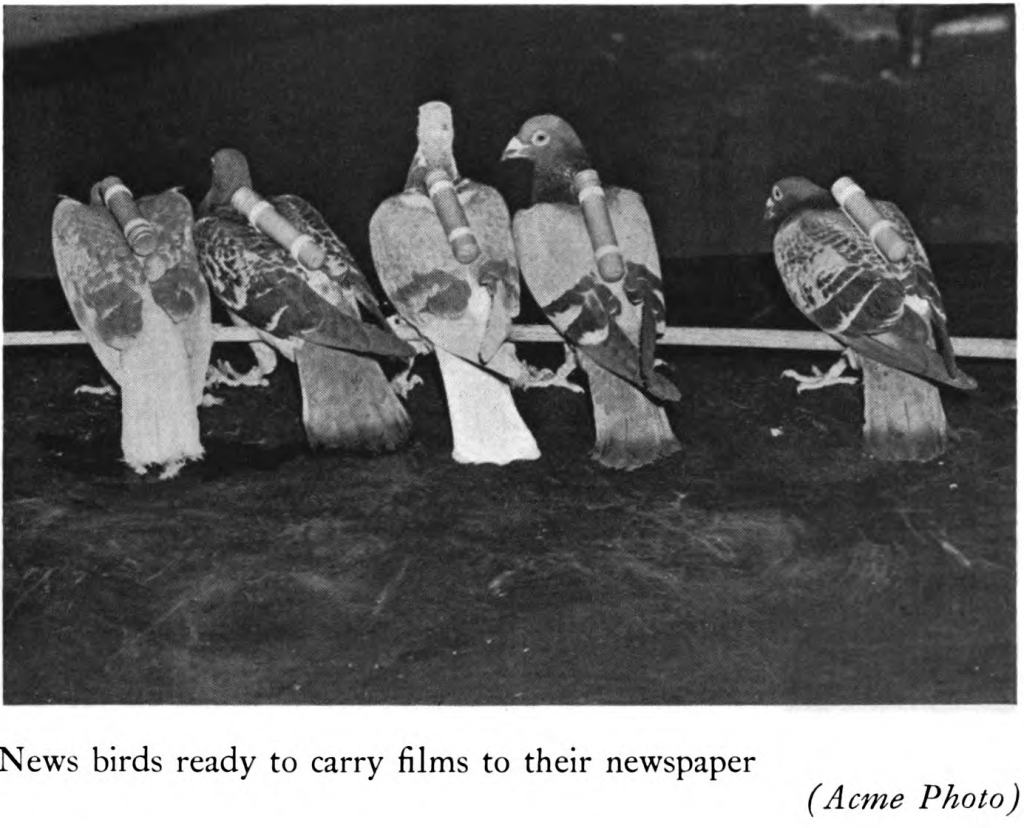

A standard operating procedure existed for ensuring proper transmission of the negatives to the newsroom. After taking a picture, the photojournalist would put their camera in a black bag and remove the film so it wouldn’t be damaged by the light. Next, the negative and a caption for the picture, written on thin onion skin paper, would be inserted into a capsule and fastened either to the pigeon’s leg or its back via a chest harness. The pigeon then would be released, flying back to the roof of the newspaper’s offices within a few minutes. The negative would be rushed to a darkroom, where it would be developed into a photographic print fit for circulation.

In a remarkable illustration of the efficiency of this process, a newspaper pigeon flew from an ocean liner bearing a negative of the ex-mayor of New York City, Jimmy Walker, who had been hiding out in Europe since he resigned in disgrace several years earlier. By the time Walker departed the ship, the photo had been developed and printed in the paper’s latest edition. Much to the delight of the paper’s pigeon manager, a photographer snapped a picture of Walker buying a copy.

Into this milieu was born Braddock, a grey-checkered cock. He was likely named for the then-reigning heavyweight champion James J. Braddock rather than the ill-fated general of the French-and-Indian War. Braddock worked for the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) Service, Inc., a newspaper syndication service that supplied photographs to its client papers. In 1935, Robert J. Ronchon, the commercial manager for the syndicate, had installed a massive pigeon loft on top of the 363-foot skyscraper where NEA’s New York office was located. Weighing 10,000 pounds and measuring 27 feet long by 6 feet wide, the loft was declared by Sergeant Clifford Poutre of the US Army Signal Corps to be “the most scientifically built house for racing pigeons” in existence. It was subdivided into 4 coops, each of which was capable of housing 75 birds, and a small office for an attendant to lounge in while awaiting incoming despatches.

After several years of carrying photos to NEA’s rooftop loft, Braddock was recruited for a special mission in the spring of 1939. A 10-year-old girl named Margaret Gillen had recently been admitted to a New York hospital for several operations. While she recuperated, a sheet of goldfinch stamps issued by the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) caught her fancy. Margaret decided right then and there that she wanted a pet goldfinch of her own—it could sing to her while she was in the hospital. She wrote to the president of the NWF, who happened to be famed cartoonist J. N. “Ding” Darling, asking if he could get her one. Darling saw an opportunity to make a little girl happy and promote the upcoming National Wildlife Week. He wrote back to Margaret, telling her that he couldn’t get her a wild songbird, but would do the next best thing.

Darling bought a white, roller canary from a petshop in Union City, New Jersey. To get it to Margaret, he reached out to Ronchon, inquiring whether it was possible for one of NEA’s pigeons to deliver the canary to New York. Ronchon, accepting the challenge, selected Braddock for the task. A special, 5-inch aluminum tube was designed by Ronchon for the canary—it featured four tiny stabilizers, rounded ends, and a spinning nose that could draw in cool air for the passenger’s comfort. When loaded up with a canary, the tube weighed the same as a 3-cent letter.

The tube was secured to Braddock’s back through a chest harness. A few test flights occurred involving a different canary named “Tessie Testpilot.” These proved to be a success. “On several flights,” reported an NEA correspondent, “Miss Testpilot came through without a single ruffled feather and feeling chipper enough on ‘stepping down the gangplank’ to chirp a bit.”

Finally, it was time for Braddock to deliver Margaret’s canary. He was released from Elizabeth, NJ and flew towards New York City. A stiff wind impeded his progress, but after 42 minutes, he landed on NEA’s rooftop with the canary in tip-top shape. A team of journalists escorted the canary to Margaret. A flurry of photographs taken that day show Margaret’s genuine joy in receiving her new pet. In a token of her appreciation, she named the bird Darling.

Braddock’s canary caper was the biggest moment of his career with NEA. He soon returned to the daily grind of news reporting. With the US’s entry into World War II, however, Army officials fretted that the Signal Corps’ peacetime supply of pigeons would not be enough for wartime. They appealed to fanciers to donate their bids. Evidently, NEA felt the call of duty—at some point in 1942 or 1943 (the date is not certain), Braddock and 99 of his peers were shipped to Fort Monmouth. No further information can be found about his wartime service. Given his advanced age, Braddock was probably used for breeding purposes. Thanks to the work of pigeons like Braddock, the Signal Corps had more than enough birds by early 1944.

Even though Braddock may not have had an illustrious military record like Cher Ami or the Mocker, he gave up his career when his country came calling. For that, we salute him.

Sources:

- Brown, Wilfred, “Trained Birds Deliver Messages Faithfully in War and Peace,” The Daily Advertiser, Jan. 20, 1940, at 5.

- Cothren, Marion, Pigeon Heroes: Birds of War and Messengers of Peace, 36-39, (1944).

- Lower, Elmer, “Pigeon Carries Canary on First ‘Piggy-Back’ Flight,” The Chickasha Daily, Mar. 23, 1939, at 4.

- Misurell, Edwin, “The Army Hatches a New Class of Recruits,” The Salt Lake Tribune, Nov. 27, 1938, at 73.

- Jones, Robert W., Journalism in the United States, at 554 (1947).

- Ross, Paul, “Swift, Feathered Couriers Start NEA Newspictures on Way to Olympian,” The Olympian, Oct. 30, 1938, at 11.

-

Birds of Prey vs. Pigeons of War

Pigeons and birds of prey have had a troubled relationship since the beginning. As nations rushed to set up military pigeon services in the 19th century, officials devoted ample resources to preventing bird-on-bird attacks. This was a serious concern for militaries. Hawks, falcons, and even owls could quickly annihilate an entire flock of pigeons during a training flight. In wartime, an enemy force could train falcons to intercept military pigeons. Aware of these issues, the United States Army waged war against raptors for decades.

The US Army’s initial efforts at keeping pigeons were sabotaged by a marauding hawk. In 1878-79, Colonel Nelson Miles requested a dozen homing pigeons from the Signal Corps for use on the Great Plains. As commander of the 5th Infantry, Col. Miles possessed a keen interest in maintaining communications amongst his troops while they were out in the field. Having achieved success with the heliograph—a semaphore system that signals by flashes of sunlight reflected by a mirror—he tried his hand at setting up a pigeon service. While some encouraging results were obtained, Miles reported that he was “troubled by a small hawk, which greatly disturbed the birds in their flight, occasionally destroying them.”

After a long dormancy, the US Army established a fully-fledged pigeon service upon the country’s entry into World War One. Impressed with the birds’ abilities during the War, Army officials decided to keep its pigeons afterwards, setting up a central station at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey and multiple lofts across the country and its territories. Before too long, Signal Corps pigeoneers assigned to care for the birds observed that hawks and falcons were plaguing their flocks, especially at the Panama Canal Zone lofts. There, one sergeant complained that his birds “are nearly always chased by hawks.” “Only recently . . . one of those big fellows dropped into the flock taking a very promising youngster and crippling [another],” he lamented in a letter to a fancier magazine.

To address this issue, officials at Fort Monmouth investigated a time-honored technique developed in China—pigeon whistles. As their name suggests, pigeon whistles are whistles that are attached to the birds before a flight. As the pigeons fly, air passes through the whistle, emitting a unique sound, not unlike the mechanical hum of a drone. Dating back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279 C.E.), they originated as a way for the military to send signals during war, but pigeon fanciers soon discovered they repelled birds of prey. Two types of whistles had been developed over the years. The former resembles a sort of panflute, with up to five bamboo tubes placed side-by-side, while the latter is made from a gourd, bearing a mouthpiece and around ten to twelve holes.

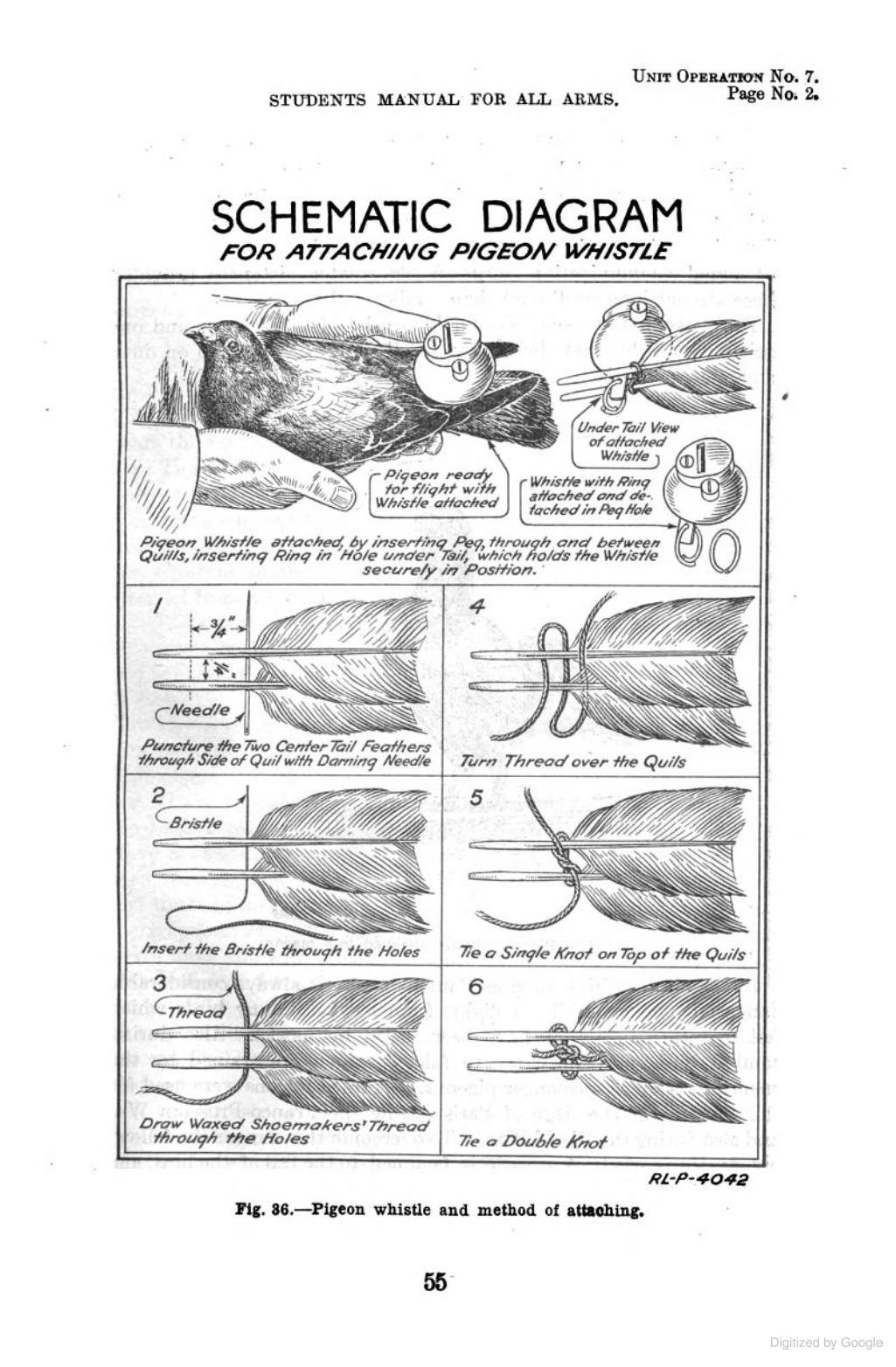

The Signal Corps imported a number of the whistles from China for use at Fort Monmouth. Throughout the ‘20s, pigeoneers experimented with the whistles. In the 1924 edition of the Army’s pigeoneer manual, soldiers were instructed to use pigeon whistles to ward off hawks. A detailed schematic explained how to install the device: a pigeoneer would need to pierce the bird’s two center tail feathers through the side with a needle, thread a piece of string through the holes, and tie a double knot on top of the quills. From this base, a whistle could be secured to the pigeon for as long as the pigeoneer desired. The manual, nevertheless, noted that the whistle was still a work in process—”Experiments are being carried on to determine the actual value of the whistle.”

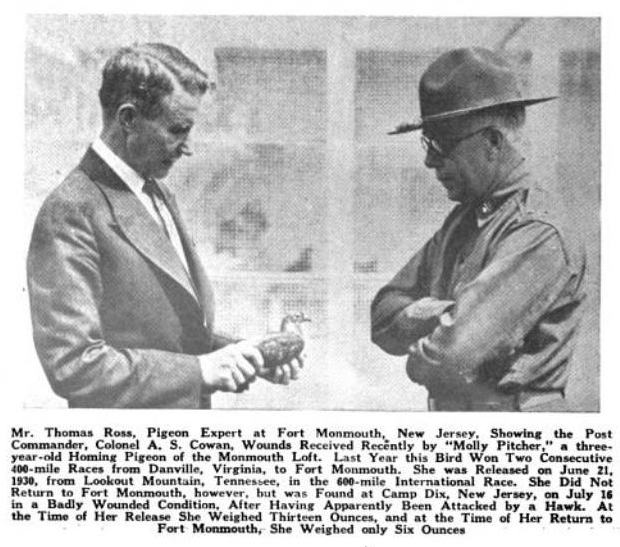

In spite of these efforts, officers at Fort Monmouth reported in August 1930 that the experiments had not proved successful. They undoubtedly had a fresh incident in mind. Just two months earlier, a hawk had brutally attacked one of the Signal Corps’ finest pigeons, Molly Pitcher, a three-year-old pigeon that had beaten over 3,000 birds in competition races. Molly had been released in a 600-mile International Race near Chattanooga, Tennessee on June 21st, but failed to show at her loft. On July 16th, she was spotted at nearby Camp Dix in New Jersey, walking between tents and unable to fly. Her trainer picked Molly up in person, noting that she had been severely wounded by a hawk. Although she recovered, Molly’s left wing remained permanently limp, ending her days as a flyer for Uncle Sam.

This seemed to inaugurate an unfortunate trend, with two unprecedented raids occurring within weeks of each other in 1932. In February, a hawk spotted a flock of Signal Corps pigeons out on an exercise flight. It followed them back and flew through the entrance trap into the loft—a feat never before accomplished by a raptor. Suddenly, over 100 birds were in extreme danger, including war heroes Mocker and Spike. The hawk instantly seized the Pride of Monmouth—a prize-winning homer who was being used in experimental flights along the earth’s magnetic meridian—and tore off his head. Before the hawk could do further damage, a sergeant who happened to be in the loft bashed it over the head with a stick. Dazed momentarily, the hawk then attacked the sergeant, scratching his arms and hands until he knocked the bird out. One the largest hawks ever to be seen at the Fort, it was put on display in a cage.

Just weeks later, in April, a group of night-flying pigeons were about to enter their loft when a large owl swooped down and grabbed Evening Star, one of the younger night-flyers. The owl tore up the pigeon’s back so badly that it died a few moments later. A private dashed off into the barracks to grab a shotgun and shot the owl after it had landed in a tree. Never before had an owl terrorized the Fort’s pigeons. As experiments with night-flying were a priority, this was a new risk for which the Signal Corps was ill-prepared.

Fed up with these ambushes, Colonel Arthur S. Cowan, the commanding officer of the Fort, immediately ordered that an armed guard be posted outside the pigeon lofts whenever the pigeons were in flight, day or night. Wielding a shotgun, the guard would patrol the areas around lofts on the lookout for hawks during the day and owls at night. In spite of this new measure, it appears that experiments with pigeon whistles continued unabated—in 1938, the Signal Corps announced that it would add them to the Pigeon Service’s wartime equipment.

During World War II, the US Army worried that birds of prey, whether wild or in the employ of the enemy, would be a greater danger than bullets or shrapnel. “So far in the Philippines,” reported one soldier, “hawks have proved to be a greater enemy of the pigeons” than the Japanese. Each Army loft was provided with a 12-gauge shotgun. Breeding efforts focused on producing dark-feathered birds, as those with lighter plumage were deemed “hawk-bait.” It’s unclear if pigeon whistles were still being used—a Signal Corps field manual from 1944 does not mention them.

Hawks continued to menace the Signal Corps’ pigeons until the unit was disbanded in 1957. Experiments testing the pigeons’ abilities to function in extreme cold during the winter of 1949-50 were derailed when Arctic falcons decimated their ranks. In spring 1952, a Signal Corps general gave a press conference about the pigeons’ activities in the Korean War. Once again, they had encountered their old enemy. “Hawks seem to find out where pigeons are stationed and hang around. . . . Our soldiers have to get out with shotguns,” he reported.

In spite of these repeated assaults, the Pigeon Service performed admirably in three major conflicts. It’s a testament to the resilience of the pigeons and pigeoneers that these calamities did not render the Service ineffective.

Sources:

- “Army Signal Corps Maintains School for Carrier Pigeons,” The Transcript-Telegram, Aug. 18, 1930, at 8.

- Bergne, Thomas, “Results of Night Flying in the Canal Zone,” The American Pigeon Journal, Vol. XII, No. 2, February 1923, at 91.

- Burkhimer, William, Memoir on The Use of Homing Pigeons for Military Purposes, at 8, 10 (1882).

- Eubanks, L.L. “Pigeon Whistles,” The Calgary Herald, Dec. 28, 1929, at 29.

- Farneti, Milo, “Army Still Makes Use of Pigeons,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Mar. 4, 1952, at 6.

- Hunter, Rex, “On Wings and a Prayer,” The Nebraska State Journal, Jul. 7, 1944, at 8.

- “Molly Pitcher, US Army Pigeon, Gets Radio Publicity,” The Bangor Maine, Jul. 29, 1930, at 20.

- “Owl Slashes Prized Pigeon; Fort Monmouth Posts Guard,” Asbury Park Press, Apr. 9, 1932, at 1-2.

- “Pigeon Hawk Slaughters Pride of Monmouth After Pursuing Birds Into Loft,” The Daily Record, Feb. 3, 1932, at 1.

- “Pigeons Save Lives in War Against Japan,” The Indianapolis News, Aug. 16, 1945, at 34.

- Sperry, James, “The Homing Pigeon,” Veterinary Bulletin for the Veterinary Corps, Vol. XI, No. 4, Apr. 11, 1923, at 251.

- “The Army’s Winged Messenger,” U.S. Army Recruiting News, Vol. XII, No. 23, Dec. 1, 1930, at 7.

- “Through the Telescope,” U.S. Army Recruiting News, Vol. XII, No. 16, Aug. 15, 1930, at 12.

- United States Army, The Pigeoneer, at 55-56 (1924).

- “Vivid Tale of New Aerial Foe Combat Told by Army Man,” The News, Feb. 4, 1932, at 10.

- “War Hero Pigeons No Longer Active,” The Evening Star, Sep. 28, 1930, at 10.

- “Whistles Added to Army Pigeon War Equipment,” The Springfield News-Leader, Sep. 16, 1938, at 14.

-

Pigeons in the Iraq War

When people think of military pigeons, they usually associate them with a bygone era. It may come as a shock to many to learn that pigeons were actually used by the United States military in the 21st Century. This week, we take a look at an interesting chapter of the Iraq War involving pigeons and chemical detection.

Throughout February 2003, the 1st Marine Division was stationed at Camp Matilda in Kuwait, waiting for the command to march toward Baghdad. As they prepared for the invasion, military planners feared a chemical attack might be launched by Saddam Hussein’s forces. Marines were given smallpox and anthrax vaccines and outfitted with gas masks, rubber boots and gloves, and charcoal-lined camouflage suits. Yet the Division’s chemical detection systems often gave false positive readings when in contact with petroleum-based vapors—an element that could not be avoided in oil-rich Iraq. A false reading would require troops to put on their protective gear, impacting their performance and wasting precious time.

To remedy this issue, Chief Warrant Officer Stacy Jeambert advocated for the use of a Sentinel Species, an organism that could be used to detect early indications of chemical agents in the air—a canary in a coal mine is a classic example. If the bird drops dead, it’s a sign that folks need to immediately evacuate the area. The Marines even had a history of using birds as Sentinel Species. During the Gulf War, a “sizeable number of parakeets” were provided to the 2nd Marine Division for chemical detection. Chickens were also used for this purpose—Jeambert had kept five of them nearby when he served in that conflict.

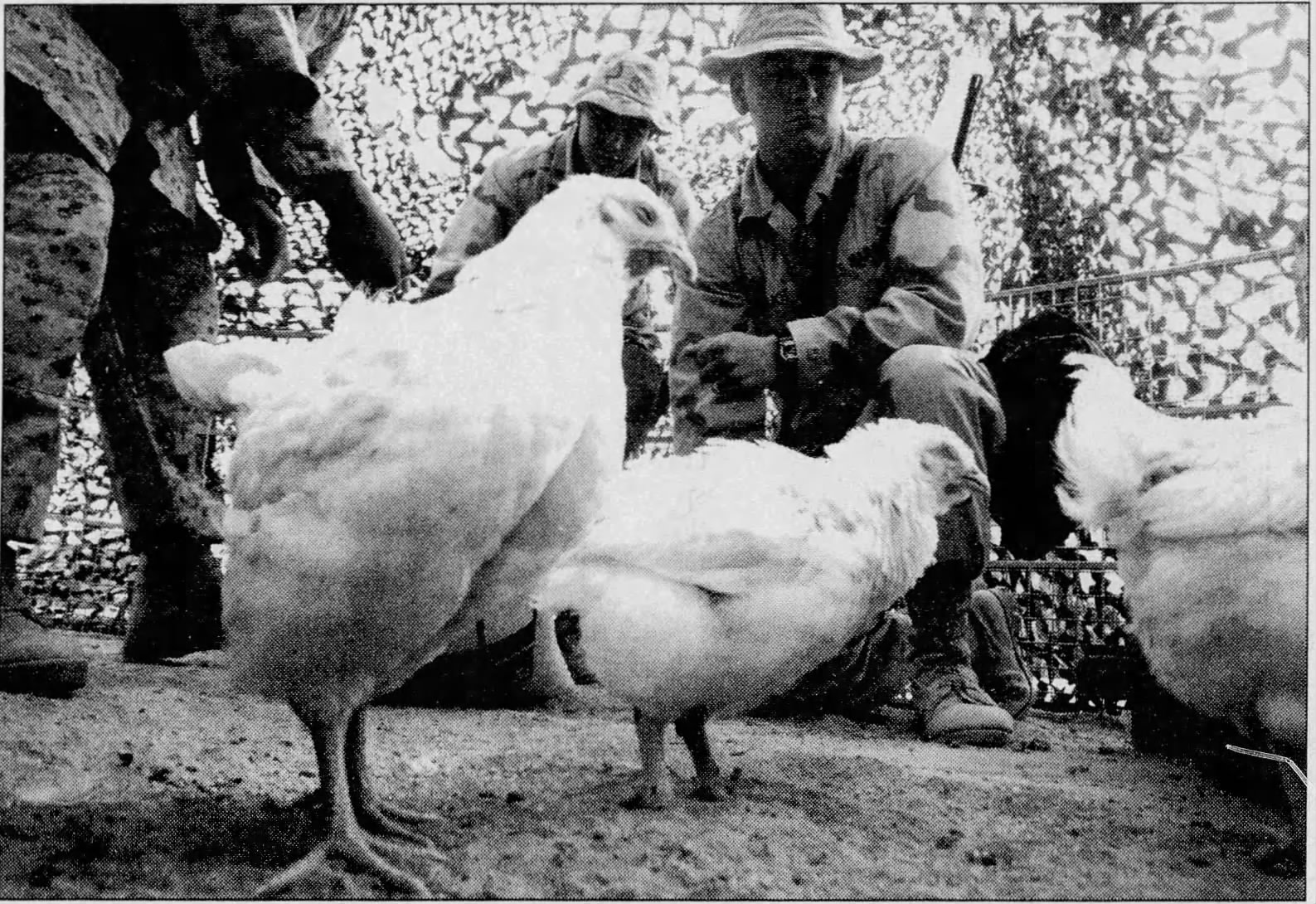

Drawing on his past experiences, Jeambert arranged for the Division to purchase 200 chickens from a young Kuwaiti entrepreneur. A chicken coop was built for the birds and plans were made to “fatten them up” before using them for detection work. Afterwards, the chickens were to be caged and placed in a truck near the front of base, where their constant clucking would indicate that all was well.

Within days, however, problems quickly surfaced. Several of the chickens wandered off into the desert, while others possibly were eaten. One week in, most had died from the arid desert climate—it was claimed that as laying hens, they simply were not suited to the desert’s cold nights and sandstorms.

The Division turned next to pigeons, a much hardier bird. On March 14th, the Division procured 175 from a local bird dealer for about $55 a piece The birds were handed out to regimental combat teams and battalions, placed under the charge of lance corporals. Officials took deliberate efforts to ensure the pigeons would thrive. The commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion, for instance, instructed his Marines to give the birds bottled water and find “pigeon-qualified personnel” to care for them.

On March 19th, the US military commenced its invasion of Iraq. The 1st Division’s Marines loaded their pigeons into the back of Humvees and armored vehicles before speeding out of Kuwait. During their 28-day trek toward Baghdad, the Marines kept a close eye on the birds for signs of a chemical attack. Unlike the chickens, the pigeons quickly adapted to desert life—few, if any, died. Thankfully, by mid-April, the troops had taken Baghdad without a single instance of chemical weapons being deployed. At this point, the Marines freed their pigeons from their military obligations, turning them loose into the wild.

During their time together, many of the Marines bonded with the pigeons, even giving them colorful nicknames such as Boudreaux, Outlaw, Trigger, Sarsaparilla, Jackball, and Doc. One pigeon, Pidgeodo, got to visit Saddam’s palace in Tikrit before being relieved of duty. Another bird, Petey, established a tight rapport with his unit. In their off time, the Marines fed him crackers and cooed to him. They also looked after his morale. When they set up camp in Baghdad, some Iraqi pigeons started taunting Petey with mating calls. To boost his spirits, his comrades placed a pin-up photo in his cage. In recognition of his service, his caretakers opted to take him back to Kuwait in person.

In spite of this affection, the Marines also were very much aware that, at the end of the day, their pigeons were just “another item to lug across the desert.” “It was a pet and cargo,” a Lance Corporal remarked. Moreover, not everyone was a fan of the birds—one Gunnery Sergeant grumbled that his unit’s pigeon “just sits there. And it drinks our water too.”

A 2006 history of the 1st Division’s time in Iraq provides an apt summary of the benefits the pigeons brought to the Corps:

The Sentinel Species concept was validated, and instilled additional confidence in the Marines’ ability to operate in a contaminated environment. The skepticism and humor with which this employment was met also provided valuable comic relief at a time of heightened tension. A sense of humor was a critical aspect of courage as the Marines prepared to attack into the unknown.

Sources:

- Clay, Diane, “U.S. Military Enlists Animal Aides Dogs, Sea Lions, Even Chickens Used in Iraqi Operations,” The Oklahoman, Mar. 25, 2003, available at https://www.oklahoman.com/story/news/2003/03/25/us-military-enlists-animal-aidesbrdogs-sea-lions-even-chickens-used-in-iraqi-operations/62051684007/

- Gerlin, Andrea, “Chickens Out, Pigeons In,” The Post-Star, Mar. 15, 2003, at 3.

- Groen, Michael, With the 1st Marine Division in Iraq, 2003: No Greater Friend, No Worse Enemy, at 112-113 (2006).

- “If the Parakeets Keel Over, Put on Your Mask,” Longview Daily News, Feb. 23, 1991, at 16.

- “Marines Have Pigeons Waiting in Wings to Detect Chemical Attack,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Mar. 16, 2003, at 7.

- Osnos, Evan, “With the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force,” The Chicago Tribune, Mar. 30, 2003, at 1-6.

- Peterson, Patrick, “Duty Done, Pigeon Will Fly the Coop,” The Sun Herald, Apr. 17, 2003, at 4.

- “Pigeons Are Marines’ Sitting Ducks,” Pocono Record, Mar. 14, 2003, available at https://www.poconorecord.com/story/news/2003/03/15/pigeons-are-marines-sitting-ducks/50978461007/

- Robinson, Simon, “The Chicken Defense, Time Magazine, Feb. 18, 2003, available at https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,423690,00.html

-

Saint Olga of Kyiv: A Pioneer of Pigeon Warfare

This Monday is July 11th, a date on which a number of important events have occurred. In 1804, Aaron Burr fatally shot Alexander Hamilton in a duel. 110 years later, Babe Ruth made his debut in Major League Baseball. We at Pigeons of War, however, will be commemorating the death of Saint Olga of Kyiv. A 10th-century medieval princess, Olga was an early pioneer of pigeon warfare.

Olga was born in Plesokov at some time between 890 C.E. to 925 C.E—historians aren’t exactly sure when. Of Varangian descent, at 15 years old she was married off to Igor, the Prince of Kyiv and member of the Rurikid dynasty. A relatively new realm, Kyivan Rus encompassed much of the territory that gave rise to modern-day Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. Surrounding tribes resented the principality’s ascent in stature, looking for ways to undermine it. The Drevlians—a forest-dwelling, eastern Slavic group—had paid tribute to Igor’s father Oleg for years, but stopped upon Oleg’s death. In 945 C.E., Igor traveled to the Drevlians’ capital city and demanded payment. Their response was brutal—Igor was allegedly tied to two bent tree trunks and torn in half when the trees were released.

In the wake of her husband’s murder, Olga ruled as regent for her three-year-old son, becoming the first woman to rule over Kyivan Rus. During her reign, she waged war against the Drevlians to avenge the slaughter of Igor. Achieving great success, she turned her sights toward the city where her husband had been killed. A yearlong siege of the capital bore little fruit, so the princess plotted a bold scheme. Olga informed the inhabitants that she would end the siege for a small price:

Give me three pigeons and three sparrows from each house. I do not desire to impose a heavy tribute, like my husband, but I require only this small gift from you, for you are impoverished by the siege.

Stunned by this meager demand, the Drevlians all too happily complied. An account of what happened next paints an apocalyptic scene:

Now Olga gave to each soldier in her army a pigeon or a sparrow, and ordered them to attach by a thread to each pigeon and sparrow a piece of sulphur bound with small pieces of cloth. When night fell, Olga bade her soldiers release the pigeons and the sparrows. So the birds flew to their nests, the pigeons to the cotes, and the sparrows under the eaves. Thus the dove-cotes, the coops, the porches, and the haymows were set on fire. There was not a house that was not consumed, and it was impossible to extinguish the flames, because all the houses caught fire at once.

As the townspeople fled the inferno, Olga ordered her soldiers to capture them—some were slain on the spot, others enslaved. A few were spared, commanded to pay a heavy tribute to Kyiv. The Drevlians troubled the princess no more during the rest of her reign.

Olga reigned until her son came of age. Not much information is available about her years as regent, aside from her conversion to Christianty in the 950s. For her efforts to Christianize Kyivan Rus, Olga has been canonized in both the Russian Orthdox and Roman Catholic churches. Her feast day is July 11th, the traditional date of her death. She is considered the patron saint of widows and orphans.

Olga really should be considered the patron saint of pigeon warfare. Indeed, her use of pigeons as actual weapons presaged concepts envisioned in the Twentieth Century. In 1943, American psychologist B. F. Skinner approached military officials with a plan that would use pigeons to guide bombs. The military was skeptical, but given that there was no way to guide missiles at the time, it agreed to finance “Project Pigeon.” Granted $25,000 to investigate this concept, Skinner developed a nose cone for a missile that had three electronic screens and three spots for pigeons. The pigeons would be trained beforehand to recognize a target and to peck at it when it moved away from the center of the screen. Theoretically, when the missile was launched, the birds would see an image of the target on the electronic screen and start pecking if the image moved. Their pecking would activate cable harnesses attached to the birds’ heads, steering the missile towards its intended destination. The missiles would not have an escape hatch, so the pigeons would be sacrificed upon impact. Fortunately for the pigeons, the military canceled the project before it could be realized.

Similarly, after the Second World War, the British military considered using pigeons as biological warfare bombs. Noting that pigeons were undetectable on radar and could be trained to home to any particular object, the head of the Air Ministry Pigeon Section proposed airdropping pigeons armed with explosive bacteria capsules over enemy targets. “A thousand pigeons, each with a two ounce explosive capsule, landed at intervals on a specific target might be a seriously inconvenient surprise,” the head of the Air Ministry Pigeon Section enthused in a 1945 report. British intelligence also investigated the possibility of “training pigeons to fly into searchlights armed with an explosive charge.” Neither recommendation was pursued.

We certainly don’t endorse using pigeons as weapons. Their amazing homing abilities vastly outweigh any potential they may have as incendiary devices. It’s best to keep in mind, though, that the medieval era was harsh and unforgiving, especially for a recently widowed princess. Olga used her brains to triumph over the enemy, saving her young son and kingdom, and we think that is worthy of celebration.

Sources

- Bowcott, Owen. “RAF Planned Kamikaze Anthrax Pigeon Squadron.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 21 May 2004, https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2004/may/21/artsandhumanities.military

- Cross, Samuel and Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd, The Russian Primary Chronicle, Laurentian Text, at 81 (1953).

- “Pigeon Terrorists Were to Drop Bombs.” Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 21 May 2004, https://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2004/05/21/1113180.htm.

- Stromberg, Joseph. B.F. Skinner’s Pigeon-Guided Rocket. Smithsonian Institution, 18 Aug. 2011, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/bf-skinners-pigeon-guided-rocket-53443995/.

-

Pigeons in the Arctic, Part II: Cold Weather Training

With origins in Northern Africa and the Middle East, homing pigeons clearly aren’t meant to be in the Arctic. Yet, these birds have repeatedly found themselves recruited for service in one of the coldest, most inhospitable regions on the planet. This week, we’ll take a look at the US Army’s attempts to prepare its Pigeon Service for Arctic operations.

Throughout its history, the abilities of the United States Army’s Pigeon Service would be tested in a variety of climes. The Great War saw the birds serve mainly in the temperate climate of continental Europe, while in the Inter-War Period, the Army erected lofts in the Panama Canal Zone, Hawaii, and the Philippine Islands, where hot weather was the norm. But how would the Army’s birds perform in places where cold weather was the default? This was an important concern, as the United States shares a border with an Arctic nation (Canada) and possesses its own Arctic territory (Alaska). Bearing this in mind, Army officials embarked on a multi-year process to gauge how its pigeons would function in the Arctic.

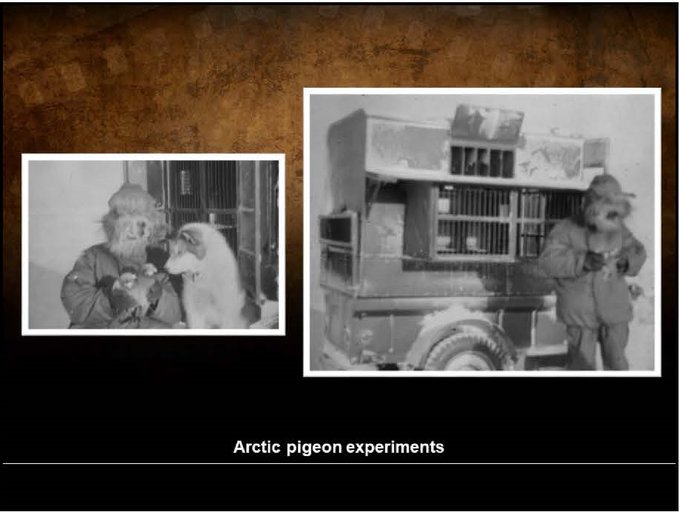

An opportunity to expose the Army’s Pigeon Service to extreme cold arose in Alaska in the early ‘40s. The US military had begun fortifying the region a decade earlier, after years of neglect. The Army Air Corps received authorization from Congress to construct a research airfield for cold weather testing near Fairbanks, Alaska. Built in 1940, the Ladd Army Airfield focused largely on testing aircraft performance and maintenance in freezing temperatures. Researchers also explored other aspects of Arctic operations, including communications. As pigeons were still being used by pilots for emergency communication, this meant they were a natural subject for experimentation.

To that end, a shipment of homing pigeons from Fort Monmouth, New Jersey arrived in December 1941 for cold weather training. A newspaper article published at that time mentioned that the pigeons would be trained to return to mobile lofts under frigid conditions. A portion of the birds’ training would also involve being released from Army bomber planes. Signal Corps Pigeoneers traveling with the pigeons claimed the birds would perform well in cold weather given that “their body temperature is as high as 107 degrees.” Nevertheless, to ensure the pigeons’ wellbeing, the mobile lofts would be heated and the birds allowed to hang out in a stationary loft that had been erected near the base’s radio transmitter. An assessment of how the birds performed in the cold weather is not readily available, but evidently, the experiment ran for some time—from November 1941 through October 1943, approximately 275 pigeons passed through Ladd Field and other military installations in Alaska.

Following a brief pause during the Second World War, the US Army re-examined the need for Arctic operations, now that the Soviet Union had become the enemy. During the early years of the Cold War, the US would focus on training its troops in the Canadian Arctic. An ideal site was Fort Churchill, an American military facility situated on the Hudson Bay in the northeastern corner of Manitoba. Temperatures in that area had been known to drop to 67 degrees below zero.

In the winter of 1948, a consignment of Signal Corps pigeons found themselves bound for the Great White North. Army officials took them on flights for several weeks in subzero temperatures. Initial results were not promising. In spite of weeks of training, the Army’s birds managed to fly no more than 25 miles in a day—far below the 500 miles a day the birds flew when south of the border. Major Otto Meyer, the Chief of the Army’s Pigeon Service, summarized the results. “They fly at greatly reduced speeds in the northland and navigate smaller distances,” Meyer stated to a Canadian newspaper. He speculated that sunspots—rather than cold weather—might be behind these issues. “We have found that the magnetic force of the earth is one of the most important factors in giving the pigeon its uncanny ability to return to its starting point,” Meyer explained, “but the sunspots up north tend to disrupt the pigeon’s flight and lessen its speed.”

To determine why the Army’s pigeons were having such trouble performing in cold weather, 70 pigeons and eight Pigeoneers traveled to Fort Churchill in November 1949 for additional testing. Army researchers also wanted to crack the mystery behind the pigeons’ homing abilities, seeking to use this understanding to develop pilotless ships and airplanes. Over 7 weeks, the pigeons were tested on flights that ranged from a quarter of a mile to 10 miles. Each bird had been trained to make flights up to 200 miles back in the States. Unfortunately, the group experienced high mortality rates. Of the 70, 51 had died by the middle of January. Meyer blamed over half the deaths on hawks. “Hawks are the greatest enemy of the pigeon in the north.” Foxes, cold weather, and training accidents were responsible for the rest. For those that survived, the intense cold hampered the pigeons’ flying abilities. “Taken out several miles and released,” reported the Calgary Herald, “they would simply scoot back into the loft instead of heading for home.”

Despite two years of bad results, Meyer remained undaunted. He planned to return to Fort Churchill with more Signal Corps pigeons the following year. As a baseline against which to compare their performances, Meyer sought pigeons born and bred in Western Canada, believing that these birds would be more accustomed to the severe climate. By spring 1950, he’d reached an agreement with pigeon fanciers in Edmonton for them to supply the Army with their birds. One fancier expressed doubt that his birds would fare any differently. “When the temperature drops below zero, human beings are happy to stay at home. Pigeons are no different.” In November, 70 more Army birds trekked northward for a third round of experiments, accompanied by specialized Arctic equipment such as hot water feeders, newly designed lofts, and training baskets. Frustratingly, the results of this round of testing cannot be found online, but suffice it to say, they must have been disappointing, as the Signal Corps never again sent its pigeons north.

In retrospect, it seems quite obvious that pigeons are not cut out for Arctic service. Still, one can’t blame the Army for trying to see if it was possible. After all, pigeons have proven their merit in North African deserts and Southeast Asian jungles. Although the pigeons’ flying capabilities were greatly reduced in the bitter cold, the birds gave all they could for the cause. For this reason, we at Pigeons of War feel this chapter in the US Army’s Pigeon Service is worthy of commemoration.

Sources:

- “Aeronautics Experts Test Homing Pigeons,” Nanaimo Daily News, Dec. 6, 1949, at 1

- Coates, John B.,The United States Army Veterinary Service in World War II, at 233 (1961).

- “Hawks Kill Many U.S. Army Carrier Pigeons,” Calgary Herald, Jan. 11, 1950, at 28.

- Matthew S. Wiseman “The Development of Cold War Soldiery: Acclimatisation Research and Military Indoctrination in the Canadian Arctic, 1947-1953.” Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015).

- “Pigeons Sent to Arctic Post,” Asbury Park Press, Nov. 21, 1950, at 2.

- Price, Kathy, The World War II Heritage of Ladd Field, Fairbanks, Alaska, at 5 – 7 (2004).

- Shiels, Bob, “Homing Pigeons Here Trained for Defences,” Edmonton Journal, May 31, 1950, at 3.

- “Study Flight Habits of Homing Pigeons,” The Ottawa Journal, Jan. 21, 1950, at 29.

- “Winged Squadron Prepares for Takeoff at Ladd Field,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, Dec. 20, 1941, at 1.

-

Pigeons in the Arctic, Part I: Polar Expeditions

With origins in Northern Africa and the Middle East, homing pigeons clearly aren’t meant to be in the Arctic. Yet, these birds have repeatedly found themselves recruited for service in one of the coldest, most inhospitable regions on the planet. This week, we’ll take a look at two polar expeditions—one civilian, one military—involving flights near the North Pole. In both these missions, explorers brought pigeons along with them to keep the world informed of their progress.

Throughout the nineteenth century, explorers angled to be the first to “discover” the North Pole. Nearly all of these trips involved traveling toward the Pole via ship or dogsled. However, in 1895, Swedish balloonist Salomon August Andrée announced to a packed lecture hall a new strategy—he intended to fly over the North Pole in a hydrogen balloon. As Andrée envisioned it, he and his crew would lift off from an island within the Svalbard archipelago, and steer the balloon over the Bering Strait toward either Russia, Canada, or Alaska, passing over the North Pole in the process. His scheme attracted attention from the Royal Swedish Academy, which agreed to fund the expedition. Andrée also received monetary contributions from King Oskar II and Alfred Nobel, both of whom were eager to see Sweden best its Arctic peers by being the first nation to reach the North Pole.

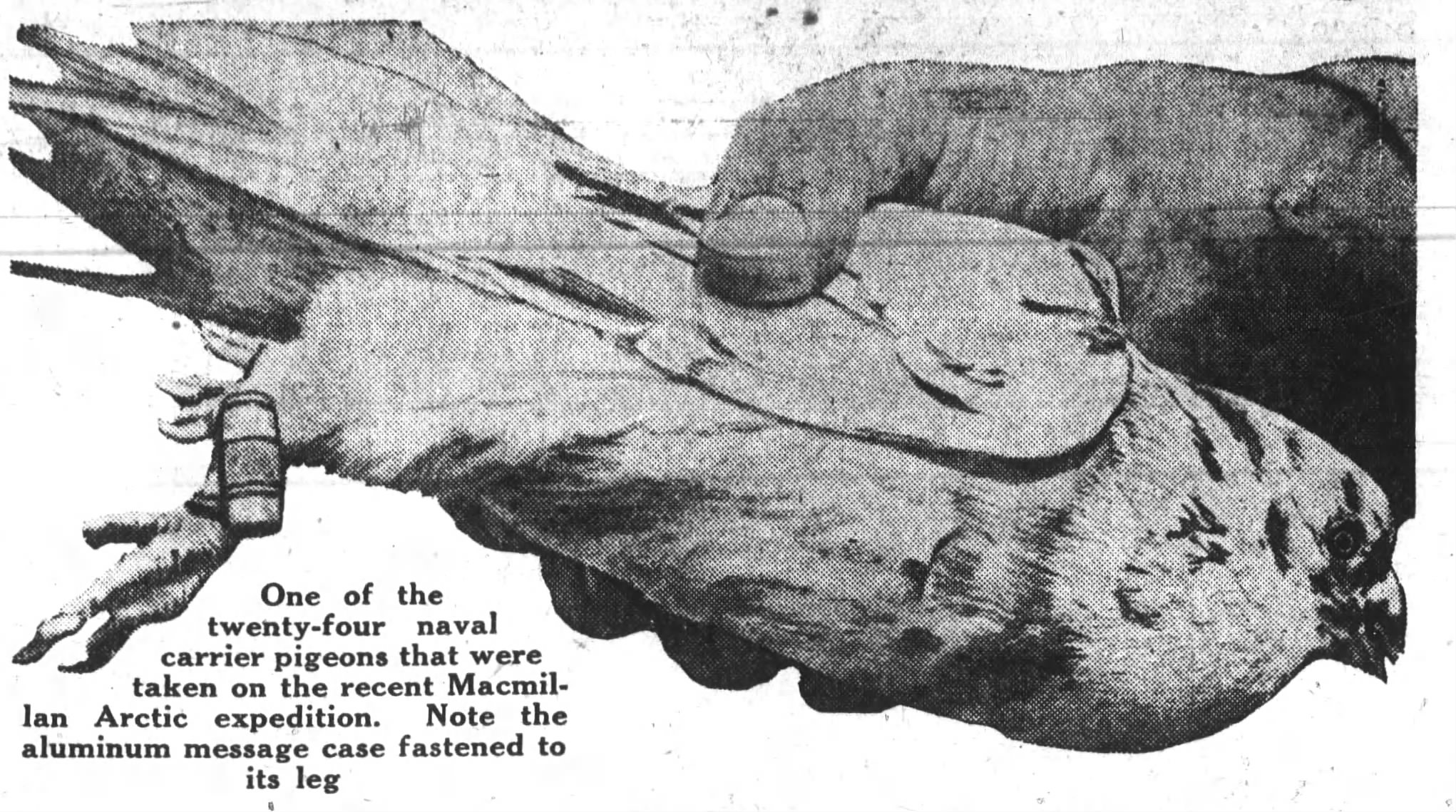

Over the next two years, Andrée diligently prepared for the voyage. He developed a dirigible balloon capable of holding a crew of three men plus provisions while staying aloft for 30 days. To communicate with the outside world, Andrée would carry with him 36 homing pigeons in wicker baskets. Donated by the Norwegian newspaper Aftonbladet, the birds had been raised in lofts in northern Norway. It was hoped that they would return to this area, bearing despatches and photographic negatives of Andrée’s progress. Printed instructions accompanying the messages would inform recipients to turn them over to the paper’s Stockholm officer.

On July 11th, Andrée launched the balloon from Danes Island, while the world waited with bated breath. On July 15th, one of the expedition’s pigeons alighted on the masthead of a Norwegian sealer vessel. The bird was shot and its message examined. It read:

“The Andrée Polar Expedition to the ‘Aftonbladet’, Stockholm. 13 July, 12.30 p.m., 82 deg. north latitude, 15 deg. 5 min. east longitude. Good journey eastwards, 10 deg. south. All goes well on board. This is the third message sent by pigeon. Andrée.”

This despatch was the last the world heard from Andrée for over 30 years. Although the message indicated that two other messages had been sent via pigeon, no other birds were ever found. In 1930, a Norwegian scientific mission discovered the remains of the expedition on Kvitøya. From reading Andrée’s diary, they learned that the balloon had crashed on pack ice after two days of heavy winds. From there, the crew slowly headed south across the drifting icescape as the Arctic winter closed in on them. By October 1897, all three men had perished.

In April 1909, United States naval officer Lieutenant Robert Peary allegedly reached the North Pole. Even though the Pole had been found, however, the United States Navy still expressed an interest in aerially surveying the area, given that military and commercial flights would inevitably cross the Pole. In 1925, the Navy agreed to provide planes and officers to the MacMillian Arctic Expedition, a joint civilian-military excursion headed by renowned polar explorer Donald MacMillan. The civilian scientists, affiliated with the National Geographic Society, planned to study the natural phenomenon of the area, while naval aviators would survey the uncharted ice lying between Alaska and the North Pole, seeking to verify land claims made by prior polar explorers. The plan was for the explorers to make base at the port of Etah—a small village on Greenland’s northwestern coast about 700 miles south of the Pole—during the Arctic summer season. From there, the naval aviators would make flights over the uncharted areas.

In preparing for the polar flights, the Navy, like Andrée, opted to bring along homing pigeons. The time, though, the birds would serve as backup communication, allowing pilots to contact officials on the ground in the event the plane’s radio failed or the plane crashed. In advance of the trip, 24 pigeons at the Naval Air Station Anacostia in Washington, D.C. were selected for polar training. The birds were put on a special diet of dried peas and vetch that was designed “to strengthen their muscles and put fat on their bodies to withstand the cold.” Trainers designed a 700-mile training course stretching from Washington to Chicago, Illinois, over which the birds were trained in 100-mile stretches at a time. The pigeons maintained an impressive flight speed averaging 50 mph over 500 miles. Naval officials weren’t too worried about the severe Arctic climate’s effects on the birds—”[Pigeons] have been flown successfully in Winter in northern Minnesota and Canada,” they remarked to the press, “when the mercury was lower than it probably will be in the Arctic regions this Summer.”

Ultimately, the group of 24 pigeons was winnowed down to the 10 best performing birds. These elite birds had the requisite pedigrees and experience for surviving in the Arctic’s severe climate. All of them had won prizes for flights, and several had experience flying from New Orleans to D.C, a distance of over 1000 miles. Their stamina was impressive as well. Each of these birds had flown 500 miles in a single day. Two of them—dubbed “Lightening” and “Admiral” in the press—had flown 1000 miles in a day. “[I]f history is to be made by pigeons in the Polar regions, ” Chief Quartermaster Henry Kubec asserted to the media,” these two will play an important part in it.”

The pigeons were loaded up in a crate and sent by express from D.C. to the naval yard in Boston. Accompanying the birds were 1400 pounds of pigeon feed and an assortment of baskets, bathtubs, drinking fountains, message books, and flying instructions. Curiously, several pounds of tobacco had been set aside for each pigeon—newspapers reported jocularly that it would “provide an ample chewing ration for the birds,” but in reality, tobacco stems make for excellent nesting material, as the stems repel vermin and keep eggs and squabs from falling out of the nest. The supplies were enough to last a year, so that in case “the steamer becomes frozen in the grip of the Arctic the birds will not suffer while waiting for the ice to break up.”

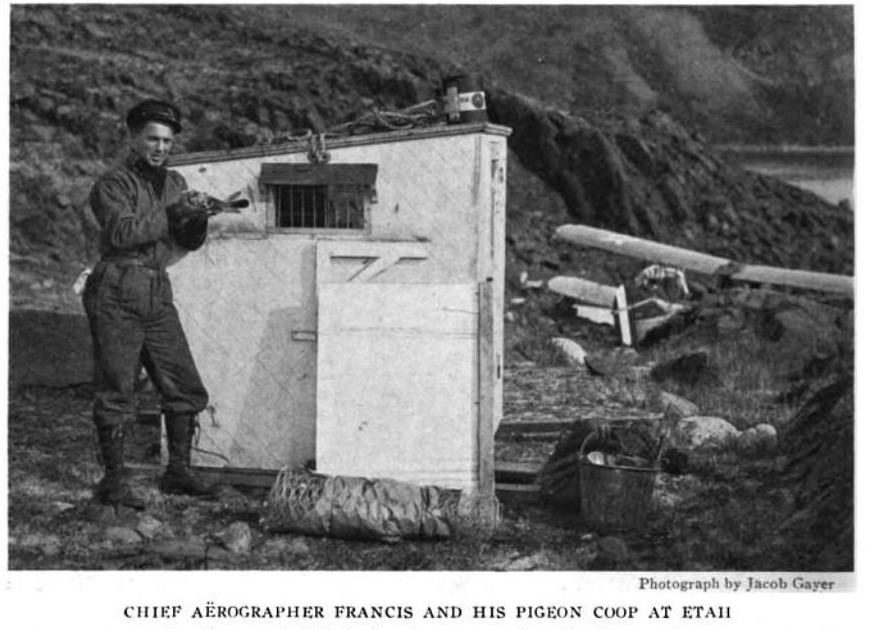

When the bird arrived at the Boston Navy Yard, a pigeon trainer introduced them to the naval aviators. The trainer explained in detail how to feed the birds and the proper temperature for their baths. The birds and their supplies were eventually loaded up with the Navy’s planes on board the SS Peary, a former Canadian minesweeper. The expedition began in earnest on June 20th when the Peary and the scientists’ ship the Bowdoin departed Maine. At a brief stop in Sydney, Nova Scotia, a pigeon trivia contest was held for the benefit of the local children. Officers aboard the Peary awarded the winner three eggs recently laid by the ship’s birds. The birds’ caretaker, Chief Aerographer Albert Francis, thought this would be a good diversion, given that the city was in the throes of a local mine strike—he had planned to eat the eggs for breakfast, anyway.

After weeks battling icefields, the explorers made it to Etah on August 1st. A pigeon coop was quickly set up on a hill overlooking a beach. On August 3rd, Commander Richard Byrd, the officer in charge of the aviators, informed the media via radio dispatch of the pigeons’ wellbeing. “Pigeons are in good shape. Will take them ashore tomorrow to orientate them.” The birds had also continued laying eggs unabated. “Two pairs of pigeons are nesting,” Byrd reported.

On August 4th, the birds were shut up inside the Etah coop for a few days so they would grow familiar with their environment. Byrd also claimed, rather condescendly, that the pigeons had been frightened by the Inuit crew’s sealskin clothing and needed this time to recuperate. For their training regimen, Francis intended to take the birds to points in the surrounding country and sea and release them on short flights back to the base. As the explorers wanted to set up a sub-base 250 miles away from Etah, it was hoped that the pigeons eventually would make regular flights between the facilities, serving as backup communication should the radio equipment break down.

Late in the afternoon of August 10th, Francis released the pigeons on their first flight from the base. Two hens immediately returned, seeking to care for their eggs. Two more had come back by morning, for a total of 4 returnees. Byrd speculated more might fly back as they grew hungry, but none ever did. After several days, Francis determined that Arctic falcons had eaten all the other birds. The likely culprit was the gyrfalcon, an extremely large falcon that thrives in the High Arctic. In spite of all their training, the Navy’s pigeons could not escape their perennial foe. “[P]igeons are not practicable for communication purposes in that part of the Arctic,” Byrd concluded in a post-expedition account.

For the remainder of the expedition, the aviators had mixed success in flying over the Arctic. The expedition headed back home in October to great acclaim. Although the pigeons didn’t live up to the Navy’s expectations, readers back in the US were nonetheless inspired by them. Around the end of August, a 12-year-old boy wrote to the National Geographic Society to see if he could get “one of the pigeons our dear Mr. MacMillan took up north with him.” A budding pigeon fancier, he desired a bird “who has succeeded in flight for I want my pet to have a name for himself.” Even well into 1926, newspapers were still publishing pictures of the birds.

In each of the above Arctic excursions, the pigeons that tagged along all had something in common—they were not the focus of the missions. As the US military gained a foothold in the Arctic, though, pigeons would receive special attention. Next week, we’ll examine the US Army’s efforts to acclimate its pigeon service to the Arctic.

Sources:

- “Andrée’s Arctic Balloon Expedition.” Wikipedia, 15 June 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9e%27s_Arctic_balloon_expedition

- Byrd, Richard, “Flying Over the Arctic,” The National Geographic Magazine, July to December 1925 Vol. XLVIII, at 519-20, at 524.

- Byrd, Richard, “Headed for the North Pole,” US Air Services, Sept. 1925, Vol. 10, No. 9, at 42.

- “Chewing Tobacco on Pigeons’ Menu While in Arctic,” Evening Star, May 16, 1925, at 16.

- “Conditions at Etah Are Told,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Aug. 3, 1925, at 1.

- Hiam, C. Michael. “Flight of the Polar Eagle: Journey to the North Pole.” HistoryNet, 11 July 2019, https://www.historynet.com/flight-polar-eagle-journey-north-pole/

- “Homing Pigeons for the Peary on Its Expedition North,” The Boston Globe, Jun. 16, 1925, at 11.

- “Inside the Macmillan Arctic Expedition of 1925.” Navy Times, 8 May 2019, https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/05/08/inside-the-macmillan-arctic-expedition-of-1925/#:~:text=In%201925%20an%20unusual%20first,young%20American%20adventurer%2C%20Lincoln%20Ellsworth.

- “Little Boy Wants MacMillan Pigeon,” The Buffalo Evening News, Aug. 31, 1925, at 20.

- “MacMillan Could Not Select Base,” The Montreal Star, Aug. 10, 1925, at 1.

- “Peary Arrived at Sydney, N.S.,” The Gazette, Jun. 24, 1925, at 8.

- “Pigeons Training for Arctic Flight,” The Evening Star, May 29, 1925, at 27.

- “Planes Visit Camp Where 18 of Greely’s Men Died,” The Boston Globe, Aug. 10, 1925, at 2.

- “The Peary Drops Anchor in Sidney, N. B. Harbor,” The Sun-Journal, Jun. 24, 1925, at 1.

-

“You’re in the Army Now!”: When Pigeons Get Drafted

In discussions about military pigeons, little attention has been paid to how the birds even entered the armed forces. Typically, there were two routes. Some pigeons were like professional servicemembers—born and raised in government lofts, all they knew was a life of military camps and discipline. Others were like draftees—prize-winning racing birds in civilian life, they suddenly found themselves thrust into an active warzone.

This latter group of pigeons provided crucial services during both World Wars. But how did governments get folks to hand over their pigeons to the military? From the 1870s through the 1940s—the golden age of war pigeons—this was an issue of concern. In the event war broke out, a country’s reserve of military pigeons would quickly be depleted. Fresh recruits would have to be drawn from the nation’s fanciers, some of whom might be unwilling to part with them.

France and Germany explored different ways in which civilian fanciers could be compelled to turn over their birds to military authorities. Influenced by recent memories of the Franco-Prussian War, the French legislature passed a law in 1877 granting the military the right to requisition pigeons from fanciers during wartime. To effectuate this law, President Jules Grévy promulgated regulations in 1885 requiring all individual homing pigeon owners and fancier societies to provide annual declarations to their local mayors detailing the number of lofts and pigeons in their possession. The mayors were responsible for compiling this information into a census and forwarding it to the officials in charge of their respective military districts.

Meanwhile, in Germany, fanciers took the lead in building closer ties with the country’s Ministry of War. A supra organization of fancier clubs was formed in 1884 with the ultimate goal of training their pigeons “to become something useful for the Fatherland in the event of war.” The association required its club members to make their pigeons available to the military if war occurred. In recognition of this sacrifice, the German government enacted a law in 1894 extending federal protection over club members’ pigeons. To avail themselves of this benefit, club members had to stamp the imperial seal on their birds’ wings.

Lagging behind its peers, the United States finally had its own military pigeon service when the Navy adopted one in 1896. Fearing that the Navy would not have enough birds in a time of crisis, several fanciers worked with members of Congress to develop legislation that would bring civilian birds into the Navy. On the eve of the Spanish-American War, the legislation was introduced into the House of Representatives and the Senate. Under the proposed law, the National Federation of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers would be required to file annually with the Secretary of State of New Jersey—the state in which the group was headquartered—information about the pigeons owned by its members and the location of their lofts. In the event that war or a civil disaster occurred, the Federation would have to turn all of its birds over to the Secretary of Navy. In exchange, homing pigeons bearing Federation leg bands would receive federal protection, with it being a crime to kill, injure, or trap them.

Critics, however, argued that the bill only protected the pigeons of only one fancier group: the National Federation of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers. While this had been the predominant homing pigeon enthusiast group in America, a faction dissatisfied with the Federation’s internal politics split off and formed their own group in December 1897. This new group, National Association of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers, had quickly become “a far larger, more powerful, progressive and representative body,” much to the Federation’s chagrin. The fanciers who had spearheaded the bill were Federation members, and thus, had carefully drafted it so as to discourage pigeon owners from joining the Association. Put off by this partisan display, legislators referred the bill to the Committee on Naval Affairs, where it ultimately died.

Thankfully, both the Federation and the Association offered up their birds to the Navy when war broke out. It was thought the pigeons could be of service for ships patrolling the coast in search of the dreaded Spanish fleet. To that end, group members in Maryland and Pennsylvania trained their birds to make flights from the coast. Once the birds graduated from training, they were handed over to naval ships stationed nearby. The Spanish fleet, however, never materialized. Instead of relaying enemy intelligence collected by scouting vessels out at sea, the pigeons were used to deliver messages from sailors to friends and family back in the city.

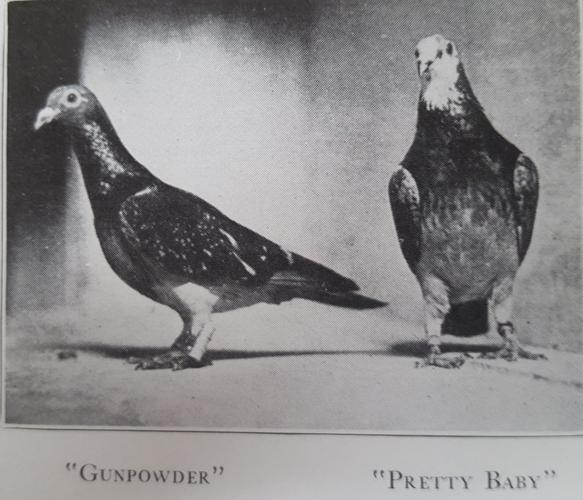

When the US Army entered World War One, it did not have a pigeon service in place. Seeing the success brought to their Allied counterparts, officials decided to set one up. Tasked with this responsibility, the Signal Corps relied on the generosity and patriotism of dozens of fanciers in getting the service up and running. The majority of these birds were used for breeding, providing the Army with its own pigeons. However, a bird donated by an American fancier, Gunpowder, delivered the Army’s first message on March 17th, 1918, carrying the message from the trenches to HQ. As the War entered its final months, the Army’s Pigeon Service found itself in dire need of 1,900 breeding pairs of “specially selected homing pigeons” for use in the American Expeditionary Force. Fearing that not all fanciers would be so kind as to donate their birds, officials sought counsel for the Army’s Judge Advocate General (JAG).

Interpreting the issue under the Fuel and Food Act of 1917, the JAG Office found that homing pigeons were “supplies necessarily required by the Government for in the prosecution of the war and are necessary for public use connected with the common defense.” In the event that a homing pigeon owner refused to turn over their birds to the War Department, the agency had the right to requisition pigeons from that owner. Officials had to issue an order to the owner describing the type and amount of birds needed and informing the individual of the provisions for compensation in the applicable statute. If the owner refused to allow officials to examine the requested birds, then they had the right to seize all the birds it wished and auction off any that weren’t needed. Because the opinion was issued just two weeks before the Armistice, the Pigeon Service never had the opportunity to exercise its newly granted requisition powers. The relevant statute was repealed in 1921, nullifying the JAG Office’s opinion.

Twenty-three years later, the US found itself at war yet again. This time, the US Army had a pigeon service in place. But military officials knew that the Army’s peacetime supply of birds would not be enough to meet the country’s mobilization needs. The vast majority of war pigeons would have to come from civilian fanciers, of which there were 12,500. While many of these fanciers had already registered their birds under a plan put into effect by the Army’s Chief Signal Officer, the Army desired more control over this vast pool of potential recruits.

In consultations with Attorney General Francis Biddle, the War Department developed a bill that would’ve enlarged the President’s authority over pigeons not owned by the United States. The bill, as introduced into Congress in April 1943, would’ve allowed the President to issue regulations governing the possession, control, maintenance, and use of all homing pigeons and their respective lofts. Violators would’ve been fined $100 or faced imprisonment of not more than 6 months, or subject to both fines and imprisonment.

The bill passed through the House, but had a frosty reception in the Senate. Senators saw the bill as an unnecessary power grab by the President’s administration. Although a sub-committee was appointed to investigate the bill, it ultimately failed to become law. Despite the Army’s fears, the nation’s fanciers rose to the call of duty. Of the 54,000 pigeons that served in the Signal Corps during World War II, approximately 40,000 were donated by fanciers. Some of these birds went to breeding centers, while others were sent to North Africa and the Southwestern Pacific. By early 1944, Signal Corps officials began informing fanciers that their pigeons were no longer needed, as the government had bred thousands of its own birds

So, unlike France or Germany, the United States never managed to implement a pigeon draft, but its fanciers were more than willing to part with their beloved birds. It’s a tribute to their character that these individuals gave away champion pigeons for free when their nation came calling. We at Pigeons of War consider these folks heroes, worthy of praise. Without them, the US military’s pigeon programs would have been doomed from the start.

Sources:

- A History of Army Communications and Electronics at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, 1917-2007 at 25, (2008).

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 126 (1888).

- “Biddle Asks Law to Regulate All Carrier Pigeons,” The Miami News, April 18, 1943, at 4.

- Blazich, Frank, “Feathers,” Army History, Fall 2020, No. 117, at 34-37, 42.

- Bulletin des lois de la République franc̜aise, Volume 12, at 796-797 (1886).

- “Carrier Pigeons for Service in War,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Mar. 2, 1898.

- “Chaffey Sending Army Gift of 34 Homing Pigeons,” The Pomona Progress Bulletin, Jan. 21, 1944, at 5.

- Der Brieftaubensport, Jean Bungartz, at 240, (1889).

- “Flock of Homers From the Dixie,” The Baltimore Sun, June 4, 1898, at 8.

- House Reports, 78th Congress, 1st Session: Miscellaneous, Vol. III, at 967-968 (1943).

- Hudson, Billy, “Pigeon Racing Local Hobby,” The Lexington Herald, June 20, 1944.

- Kidney, Daniel, “Well, Pigeons At Least, Escape Dictatorship,” The Akron Beacon Journal, Nov. 2, 1943.

- Königliche Ministerium Der Öffentlichen Arbeiten, Eisenbahn-Verordnungs-Blatt, at 259 (1894).

- “Pigeon Draft Suspended,” The Billings Gazette, Jan. 10, 1944, at 8.

- “Pigeons for the Navy,” The Baltimore Sun, May 5, 1898, at 12.

- “To Protect Homers By National Laws,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Mar. 7, 1898, at 4.

- War Department, Opinions of the Judge Advocate General of the Army: 1918, Vol. 2, at 927-928 (191).

- “War Pigeons Training,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 4, 1898, at 4.

-

Gustav: D-Day’s Finest Pigeon

This past Monday was the 78th anniversary of the Allied invasion of Normandy, popularly known as D-Day. A monumental achievement, the invasion changed the course of World War II, laying the groundwork for the liberation of France. An often ignored aspect of that day is the role pigeons played in the landings. Today, we look at one of those birds, Gustav

Gustav, a grizzle-colored male, was born in Cosham, Hampshire, England in 1942. His keeper, Frederick Jackson, was a member of the National Pigeon Service, a civilian group of fanciers who raised pigeons for war effort. When he was a few months old, the Royal Air Force (RAF)—which supplied pilots with birds to use in emergency situations— requisitioned Gustav for military service. He moved into the loft at the RAF’s base on Thorney Island, near Portsmouth and found himself under the charge of Sergeant Harry Halsey.

Officially known as NPS.42.31066, Gustav soon earned a reputation as a reliable flyer. Impressed with his skill, Gustav’s superiors recruited him for a series of special missions. In 1941, British military intelligence had developed a top-secret program for making contact with members of the resistance across Nazi-occupied Europe. Because a pigeon raised in Southern England can fly back from Northern France, Belgium. the Netherlands, and Denmark, intelligence officials determined that it would be beneficial to provide citizens of these countries with British pigeons. Between 1941 and 1945, RAF pilots dropped approximately 16,000 boxes of pigeons in these areas. Each box contained sheets of thin paper, a special pencil, a tube for storing the message, and instructions on how to write a message. The gambit paid off—over 50 percent of the received messages provided British intelligence with useful information about the enemy.

For two years, Gustav was repeatedly dropped off in Belgium. Each time, he flew back to his loft bearing important messages from the Belgian resistance. The details of these missions aren’t well known, which isn’t surprising, given the sensitivity of the information. Gustav’s courage prompted RAF officials to select him for another mission: Operation Overlord, the planned invasion of German-occupied France. Officials had selected hundreds of elite birds for use during the invasion. The birds would be presented to the troops in wicker baskets and used for carrying ammunition status reports and undeveloped film negatives as well as delivering messages when radio silence prevailed or other means of communication failed.

Instead of being loaned out to soldiers, however, Gustav would be paired up with a journalist—perhaps he was too valuable to be taken out onto the battlefield. On the morning of June 6th, 1944, an RAF commander approached Reuters correspondent Montague Taylor and gave him “a basket of four pigeons, complete with food and message carrying equipment.” The team clambered on board an Allied Land Ship Tank and settled in 20 miles away from the Normandy coast. As he watched the troops land on the beaches, Taylor hurriedly scribbled down a despatch and stuffed it into Gustav’s leg holder. At 8:30 am, he released the bird from the ship

The challenges Gustav encountered during his journey were real and substantial. The climate that day was unfavorable for flying. A fierce headwind was blowing at 30 to 50 mph, making for stiff resistance. The sun was shrouded by clouds, a major issue for homing pigeons, as they use the sun to help find their way. German-trained hawks and sharpshooters were also in the area, searching for pigeons flying overhead. But Gustav rose to the occasion. Flying non-stop over 150 miles for 5 hours and 16 minutes, Gustav entered his loft on Thorney Island at 1:46 pm. His message read:

“We are just 20 miles or so off the beaches. First assault troops landed 0750. Signal says no interference from enemy gunfire on beach. Passage uneventful. Steaming steadily in formation. Lightnings, Typhoons, Fortresses crossing since 0545. No enemy aircraft seen.”

Officials immediately telephoned London with the news. This despatch was the first report received in Britain of the Normandy landings. It was appropriate that Reuters had used a pigeon to obtain its exclusive. Nearly 100 years earlier, the news agency’s founder, Paul Reuter, had trained a flock of 45 pigeons to deliver news and stock prices between Brussels and Aachen, beating the railroad by six hours. The success of this venture prompted Reuter to open the first Reuters news room in London a year later.

For his actions, Gustav was awarded the Dickin medal, the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross. The ceremony took place a few months later, November 18th. The wife of the First Lord of the Admiralty hung the ribbon around Gustav’s neck and gave him a peck on the cheek. Another veteran of D-Day was also present at this ceremony—Paddy. Described by the press as “[a]n Irish pigeon trained in England by a Scotsman with a Welsh assistant,” Paddy held the record for the fastest flight back to Britain that day. Flying back to his loft at the RAF Base in Hurn, he traveled 230 miles in 4 hours, 50 minutes, a speed of 46 mph. A few years later in 1947, one more pigeon would receive a Dickin Medal for displaying mettle during Operation Overlord. The pigeon, fittingly named the Duke of Normandy, had delivered a critical despatch from the paratroopers of the 21st Army Group, who had landed behind enemy lines a few days earlier.

Gustav’s heroism earned him a soft berth for the remainder of the War. After the cessation of hostilities, he was returned to his original keeper, Frederick Jackson. Reports are mixed as to his fate afterwards. One story has him living in Jackson’s loft for many years, ultimately dying of old age. The other presents a much more tragic ending: while cleaning out his loft, Jackson accidentally stepped on him.

Gustav’s luster has only grown in the years since his achievements. His story partially inspired the computer-animated film Valiant, released in 2005—the same year Gustav’s Dickin Medal was publicly displayed at the D-Day Museum in Portsmouth. In 2013, a short film recreating Gustav’s actions on D-Day debuted at the Cannes Film Festival. The Imperial War Museum recently recognized Gustav as the greatest pigeon to have served the United Kingdom. We at Pigeons of War cannot disagree with that assessment.

Sources:

- Fletcher, Zita Ballinger. “How Gustav the Pigeon Broke the First News of the D-Day Landings.” HistoryNet, 7 Apr. 2022, https://www.historynet.com/how-gustav-the-pigeon-broke-the-first-news-of-the-d-day-landings/

- “Hero Pigeon’s WWII Medal on Show.” BBC News, 1 June 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/hampshire/4600865.stm

- Hutton, Robin, War Animals: The Unsung Heroes of World War II, at 292

- “Liberation of Europe: Pigeon Brings.” Imperial War Museums, https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections.

- Use of Pigeons in the Invasion of France, July 27, 1944.

- “Vital Role of Gustav the Pigeon.” The Northern Echo, 2 June 2004, https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/6989082.vital-role-gustav-pigeon/.

-

Military Pigeons in the 21st Century, Part III: China

Since the end of the Second World War, most of the world’s militaries have decommissioned their pigeon services. A few, however, have held onto their birds. In this ongoing series, we’ll take a closer look at these holdouts.

For the past two weeks, we’ve explored the world’s last military pigeon services. So far, we’ve learned that the Uruguayan and French armies still boast active lofts. Unlike their renowned ancestors, these army birds have no military obligations. The birds are frequently released at military demonstrations and public events, serving as living reminders of their countries’ past military practices. In reading about these lofts, one might be tempted to think that pigeons have no real place in a modern military.

This week, we look at a country that defies this assumption: China. Rather than downsize its pigeon service, China’s military has gone the opposite route, adding thousands of birds throughout the 2010s.

China’s use of pigeons in its militaries dates back to at least the Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644 C.E.). During that era, the nation’s armies used pigeons as couriers. The seeds of the modern pigeon service, however, were sown in the mid-20th Century. In 1937, an American officer, Lieutenant Claire Lee Chennault, traveled to China to set up the Flying Tigers, an aerial defense unit operated by American pilots to deter Japan’s invasion of the country. In setting up this program, he imported hundreds of pigeons from the US for use in communicating with forces on the ground, given that radio communication was often not possible. Following numerous trips over the Burma Road and across the Hump, the Flying Tigers disbanded at the end of the Second World War, leaving their birds behind in China.

Meanwhile, on October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) set up its own pigeon service a year later. Realizing the value of the Flying Tigers’ pigeons, officials secured these battle-hardened veterans for their nascent loft. In 1957, a series of pigeon units were set up on military bases around the country to serve as backup in case communications were disrupted. At its peak, 11 such units existed, one for each of the then-existing 11 military regions. Over the subsequent years, trainers developed an intense program for the PLA’s birds. A record was set in 1982, when a pigeon flew from Shanghai to Kunming, a distance of 1,336 miles, over 9 days. Impressed with his service, officials embalmed his body after he passed away—it is still on display.

By 2000, most of the country’s pigeon units had been shut down. Only a single military loft was left at a PLA communications garrison in Kunming in the southern Yunnan Province. Numbering a few hundred, these birds were trained to carry despatches into mountainous regions and islands in the South China Sea.

In 2010, military officials decided to reinvigorate the PLA’s pigeon service. 10,000 pigeons were to be added to the service over time, forming a “reserve pigeon army” capable of providing support to the military’s communication network in the event of a total blackout brought on by war. The pigeons would be assigned to communications bases across China’s remote and mountainous southwestern region, near the Himalayan mountains. Training exercises would focus on increasing the birds flying speed to 75 miles an hour and getting them to carry loads weighing up to 3.5 ounces.

To promote the new program, Chinese military officials embarked on a media blitz. Stories appeared in Chinese and Western media throughout 2011, featuring input from officers. “These military pigeons will be primarily called upon to conduct special military missions between troops stationed at our land borders or ocean borders,” air force military expert Chen Hong informed viewers of China Central Television. Chen Chuntao, the officer in charge of the PLA’s pigeons, explained the rationale for the expansion. “[Pigeons are the] most practical and effective short and medium distance tool for communications if there is electromagnetic interference or a collapse in our signals.”

Most media articles in the West reporting on these developments treated the subject jocularly. However, the news greatly alarmed French pigeon fancier and lawmaker Jean-Pierre Decool. Fearing that France would be left in the dust, he contacted the Ministry of Defense, stressing the need for the Army to increase its pigeon stocks. The Maréchal des Logis in charge of the French Army’s dovecote doubted the veracity of the reports. “It is true Chinese pigeon fanciers are paying a lot of money to buy pigeons, but no one knows if this is for the army.”

Tracking the pigeon program’s progress over the past decade is difficult—few stories have surfaced since the initial flurry of reports. Nevertheless, in recent years, some have argued that the pigeons aren’t being trained merely for emergency communication services. Instead, several incidents near the Indo-China border—an area in which China maintains several territorial claims—point to their involvement in a possible spy network.