-

Military Pigeons in the 21st Century, Part II: France

Since the end of the Second World War, most of the world’s militaries have decommissioned their pigeon services. A few, however, have held onto their birds. In this ongoing series, we’ll take a closer look at these holdouts.

For nearly 80 years, almost every European military had a pigeon service at one point or another. These birds served bravely in both World Wars and in minor excursions. Yet, by the start of the 21st Century, they were all gone—save for a single dovecote in France.

France’s possession of the last military loft in Europe isn’t surprising. After all, France pioneered the use of pigeons in combat during the Franco-Prussian War. From 1870 to 1871, the Prussian Army tried to cut off Paris from the outside world, but French fanciers smuggled pigeons in hot air balloons to Tours and other cities, informing government officials of their plight. French military officials, seeing the benefits, implemented a pigeon service several years later. By 1901, all of the forts on the eastern and northern frontier had pigeon stations, allowing for contact with Paris. Aside from linking forts with Paris, the French military found other uses for its pigeons. The French cavalry incorporated pigeons into their reconnaissance work, while naval ships used the birds to remain in contact with the coast.

During the Great War, the country put nearly 30,000 pigeons to work. They served courageously during the Battle of Verdun—Le Vaillant, a blue bar hen, flew through shellfire and gas clouds to deliver the last message of Fort Vaux before it fell to the Germans. Barely alive after inhaling poison gas, she pulled through and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Owing to the speed of the blitzkrieg, the French military did not have the opportunity to deploy its pigeons during the Second World War—Members of the Resistance, however, used over 16,000 pigeons in spy networks throughout the war.

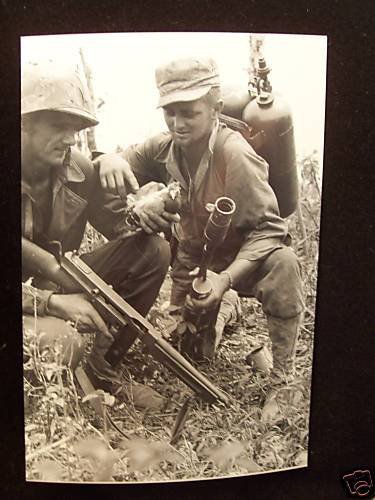

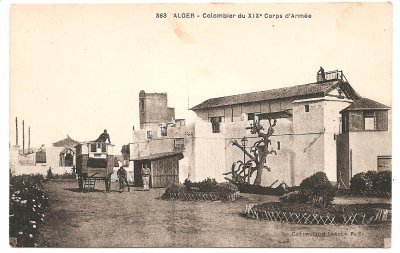

The birds later played roles in France’s subsequent decolonization wars. In the First Indochina War, the pigeons were headquartered at Fort de Cay May in Saigon. Not suited to the tropical climate, it took a year of breeding to develop a pigeon acclimated to the area. These efforts paid off, as pigeons ably assisted French outposts in An Khê and Ayun Pa, De Dak Bot and Nam Định. At Nam Định, for instance, the French troops found themselves encircled by enemy forces. Using their pigeons, they were able to request backup from Saigon. In the Algerian War, a central military loft was installed in the suburbs of Algiers. As in the prior conflict, the pigeons linked isolated outposts with military HQ.

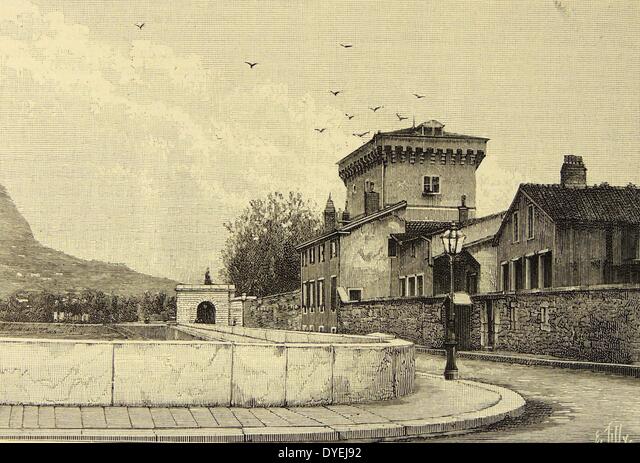

Following the Algerian War, France started decommissioning its military pigeons, seeing little need for them in an age of advanced electronics. However, a group of officers, headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Revon, pleaded with President Charles de Gaulle to spare a single dovecote for tradition’s sake. He agreed, preserving the military loft at Camp des Loges in Saint-Germain-en-Laye and assigning it to the 8th Regiment of Transmission, the unit responsible for the military’s telecommunications and information systems. In 1981, the loft was relocated to Mont Valérien, a fortress in the western suburbs of Paris.

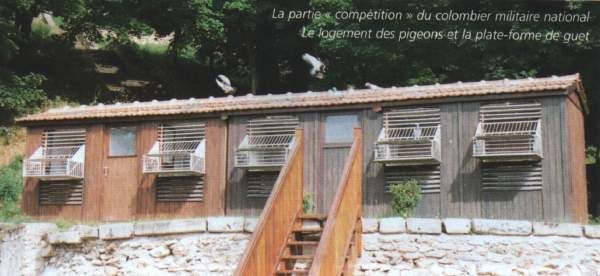

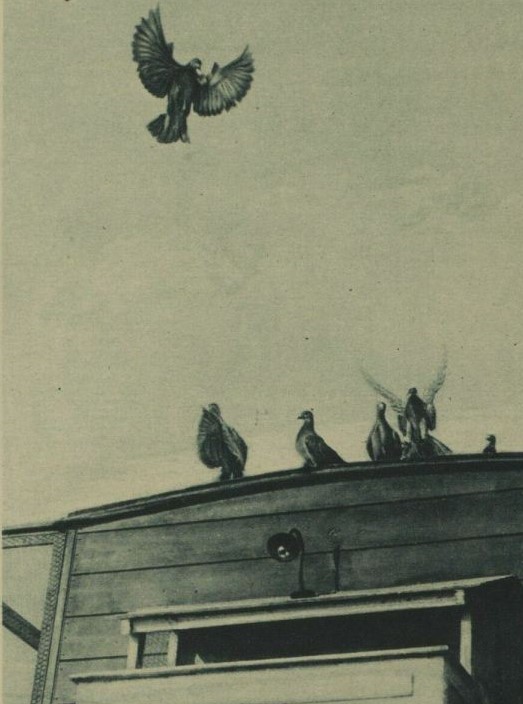

Mont Valérien’s dovecote houses around 200 pigeons, which are overseen by a single maréchal de logis, a type of non-commissioned officer. The maréchal oversees all aspects of the pigeons’ lives from the cradle to the grave: he cleans the dovecote, procures their food, selects the best birds for breeding, and provides basic veterinary care. To keep the pigeons fit for their ceremonial duties, he trains the birds for races that range from 100km to 1,000km. Their speeds vary from 60 kph to 120 kph, depending upon the weather. Tradition dictates that each new maréchal adopt one of the flock as his or her own. The current maréchal has named his protege Vaillant—the name is appropriate, as the pigeon is the champion of the loft.

Like the Uruguayan Army’s pigeons, Mont Valérien’s pigeons are used strictly for ceremonial services, taking part in civilian competitions and official military demonstrations. To educate the public further, a museum has been built near the loft, explaining the birds’ historical role in the French military. Nevertheless, the current maréchal acknowledges that they might be of use in a total blackout brought on by war. “[T]hey would need extra specialised training,” he clarifies, “but they would be fit and healthy for duty if required.” In the event of such a blackout, the maréchal has already chosen Vaillant to deliver the first official message to Paris.

One lawmaker has expressed an interest in revitalizing the Army’s pigeon service. Jean-Pierre Decool, a senator representing the Nord department, argues that the French Army should breed more pigeons. A pigeon fancier himself, in July 2012, he sent a letter to the Defense Minister, asking him to clarify France’s military pigeon strategy. The Minister wrote back, informing Decool that in the event of widespread communications failure, the country’s 20,000 pigeon keepers could be called upon to provide their birds to the military. Acknowledging that little appetite currently exists for increasing the military’s flock, Decool has also advocated for lofts to be erected near nuclear power stations “so they can keep communications going in case of an accident.” The idea came to him in the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear accident. “I said to myself that carrier pigeons could have played a crucial role in communications between the radioactive zones and the outside world, without exposing people.” As Decool envisions it, a mobile loft could be set up inside the security permit around the reactor, while a stationary loft could be established about 30 miles away. By regularly exchanging birds between the lofts, communication could be maintained in the event of an incident. So far, Electricité de France, the utility in charge of the country’s nuclear power plants, has not expressed an interest in Decool’s plan.

We at Pigeons of War applaud the French Army’s decision to keep an active loft. Not only is it a tangible reminder of 150 years of history, the loft could prove to be a valuable resource in a total blackout brought on by war or natural disaster. We encourage other European countries to follow suit and revive a military tradition that has sadly gone dormant.

Sources:

- Army ‘Needs More Carrier Pigeons’. The Connexion, 24 Aug. 2012, https://www.connexionfrance.com/article/Archive/Army-needs-more-carrier-pigeons.

- Bassine, Olivier. Un Colombier Militaire à St-Germain. 78 Actu, 16 Jan. 2016, https://actu.fr/ile-de-france/saint-germain-en-laye_78551/un-colombier-militaire-a-st-germain_12590897.html.

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 249 (1901).

- Florence Calvet, Jean-Paul Demonchaux, Régis Lamand et Gilles Bornert, « Une brève histoire de la colombophilie », Revue historique des armées [En ligne], 248 | 2007, mis en ligne le 16 juillet 2008, consulté le 25 mai 2022. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rha/1403

- Hanks, Jane. “France’s Army Platoon of Carrier Pigeons Is One of Its Kind in Europe.” The Connexion, 17 June 2021, https://www.connexionfrance.com/article/Practical/Work/France-s-army-platoon-of-carrier-pigeons-is-one-of-its-kind-in-Europe.

- Les Derniers Pigeons Soldats D’europe.” Tristan Reynaud Photographe, https://tristanreynaud.com/fr/portfolio-27463-les-derniers-pigeons-soldats-deurope.

- Marie-Pont, Julia. Des Animaux, Des Guerres, Et Des Hommes. 2003, https://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/1972/1/celdran_1972.pdf.

- Parussini, Gabriele. “French Could Return the Military’s Carrier Pigeons to Active Duty.” The Wall Street Journal, 11 Nov. 2012, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324439804578104933926157320#project%3DSLIDESHOW08%26s%3DSB10001424127887324439804578105210570961132%26articleTabs%3Darticle.

- Ulbrich, Jeffrey. Today’s Focus: Hi-Tech French Army Still Has Faithful Pigeons. Associated Press, 13 Dec. 1985, https://apnews.com/article/a20f3c8d434e397c3a3c6ba83470622b.

-

Military Pigeons in the 21st Century, Part I: Uruguay

Since the end of the Second World War, most of the world’s militaries have decommissioned their pigeon services. A few, however, have held onto their birds. In this ongoing series, we’ll take a closer look at these holdouts.

At the dawn of the Twentieth Century, Uruguay’s military joined the worldwide pigeon arms race inaugurated by the Franco-Prussian War and established its own service. A possible source of inspiration was its neighbor to the south, Argentina, which boasted 7 military lofts connecting Buenos Aires with the Andes by 1901. The exact date is unclear, but at some point before 1904, the Uruguayan Army founded a dovecote in Montevideo. Dubbed El Palomar Militar Central, the loft housed 300 birds and was overseen by an engineering battalion responsible for telegraph operations. The service soon expanded to the center of the country, with a loft in the city of Paso de los Toros, then northwards to the border cities of Rivera and Melo. These lofts, which were supplied by the Montevideo dovecote, housed 80 birds a piece. In addition to stationary lofts, the Army also raised pigeons in mobile coops, which were assigned to certain units.

The first director of the military’s Pigeon Service was an Argentinian fancier. Under his watch, he imported birds of Belgian extraction from Buenos Aires and developed training programs to link the central loft with the northern lofts. By linking the lofts, the military ensured that Montevideo would remain in contact with the northern departments in the event of a disaster or warfare.

To send messages, soldiers were provided with blank forms and advised to fill them out with a pen. Despatches were to be written like a telegram, with the author using simple, unambiguous words economically. When finished, soldiers were instructed to insert the message into a rubber or aluminum tube and affix it to the pigeon’s leg. In the event a tube could not be located, soldiers were advised to wrap the despatch in lead paper and tie it directly to the bird’s leg—this would protect the message from the elements.

In these early years, the bird’s abilities were tested during the Revolution of 1904, a brief, yet bloody civil war between the government and a rival political party. The Army’s pigeons showed their merit during this engagement, helping keep units in contact with one another. In a 1906 address before the legislature, President José Batlle y Ordóñez lauded the pigeons’ accomplishments during the insurrection. To date, this has been the only conflict in which the military’s birds have participated.

While the Army developed its Pigeon Service, civilians began forming fancier groups, the first of which appeared in the ‘20s. The military opted to foster a relationship with these groups– they helped transport civilian birds to racing competitions and even returned any lost pigeons recovered by soldiers to their owners. A law formalizing this relationship was enacted in 1943; it placed all pigeon racing activities under the authority of the Ministry of Defense. Fanciers desiring to race their birds were required to register their birds with the Ministry and provide information about the size and pedigree of the flock, with annual updates. The Ministry still regulates pigeon races to this day. “We raise the pigeons, but we are not the owners: the owner is the State because we depend on the Ministry of Defense, which still considers them a strategic resource,” remarked Jorge Risso, president of the Ariel Pigeon Society, in a 2008 interview.

During the latter-half of the century, the focus of the Pigeon Service shifted away from providing emergency communication services to performing ceremonial duties. The northern lofts were shut down in 1958, while soldiers at the Montevideo loft found themselves training their birds for racing competitions organized by fancier groups. Throughout the ‘70s, the Army released the pigeons at public events staged by the military or the state. As the pigeons participated in more races, the facilities at the Montevideo were remodeled in the ‘80s to better prepare the birds for these events. The remodeling must’ve worked, as the Army’s pigeons have won numerous prizes in subsequent years.

These days, the Uruguayan Army currently maintains a flock of 145 pigeons distributed across three coops in the Peñarol neighborhood of Montevideo. Responsibility for the birds’ care lies with the Communications Brigade No. 1, a unit tasked with maintaining the military’s electronic communications system. A non-commissioned officer, Sargento Carlos Benítez, oversees the birds, training them daily with 90-minute flight exercises. This regimen has paid off, as the Army’s pigeons have racked up some impressive records. Benítez asserts that his crew can fly up to 1,000 kilometers in a day at speeds as fast as 120 kph. The birds have made successful flights from the border city Bella Union and Porto Alegre, Brazil, traveling over 600 kilometers within just a few hours. To keep the birds in line, Benítez relies on a type of pigeon known as a pouter. In Uruguay, the bird is called a buchón—a slang term meaning informant—owing to its large crop. These pigeons can’t fly very high, so they sit out Benítez’s flight exercises. Instead, they perch on top of the coop, waiting for their loftmates to return. When the buchón spots a returning bird, it helps escort the pigeon back to its loft.

No longer needed for communication services, the Montevideo lofts now serve as living history, a reminder of how pigeons once formed an integral part of military operations. Educating the public is a primary goal. To that end, the birds have frequently been featured on television, with Army officials giving viewers glimpses of the inner-workings of the lofts in 2017 and 2019. The birds have also been brought to schools for students to witness history in action. On one occasion, children at a rural school wrote messages that were carried by the birds back to Montevideo, where the military faxed back copies. Outside of educational presentations, the Army allows for its pigeons to participate in events hosted by public and private entities. They are frequently released at football matches at the Centennial Stadium or at the celebrations of the cult of San Cono that are held annually in the city of Florida. And, of course, the birds still compete in racing competitions.

Nevertheless, there is always the possibility that Uruguay’s electrical grid could be compromised by a natural disaster or an act of terrorism. If such an event were to happen, the Uruguayan Army’s Pigeon Service would be ready, willing, and able to rise to the call of duty. Montevideo’s birds could bring information into the capital city, while the Ministry of Defense could tap into the nation’s network of fanciers and use their pigeons to restore communication with the nation’s other regions. These outcomes are not only possible, but probable, given that the Army has officers and enlisted personnel experienced in handling and training pigeons. For these reasons, the Uruguayan Army’s decision to maintain a flock of pigeons well into the 21st Century has been a wise one.

Sources:

- Batlle y Ordóñez, José, Mensaje del Presidente de La Republica, at 117 (1906).

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 237 (1901).

- Las Palomas Mensajeras: Un Deporte Que Es Arte y Pasión. LARED21, 16 July 2008, https://www.lr21.com.uy/comunidad/320319-las-palomas-mensajeras-un-deporte-que-es-arte-y-pasion.

- LLoyd, Reginald, Impresiones de la República del Uruguay en el Siglo Veinte, at 178 (1912).

- Melgar, Pablo. “Palomas Que Desafían a Twitter.” Diario EL PAIS Uruguay, El País Uruguay, 9 Mar. 2017, https://www.elpais.com.uy/informacion/palomas-desafian-twitter.html#.

- Ministerio de Guerra y Marina, Reglamento General y Regimen Interno de Los Palomares Militares, at 23-24 (1926).

- “Palomar Militar De Uruguay .” Las Palomas Mensajeras, https://laspalomasmensajeras.tripod.com/id38.html.

-

The Austro-Hungarian Military’s Pigeon Service: 1875 – 1918 A.D.

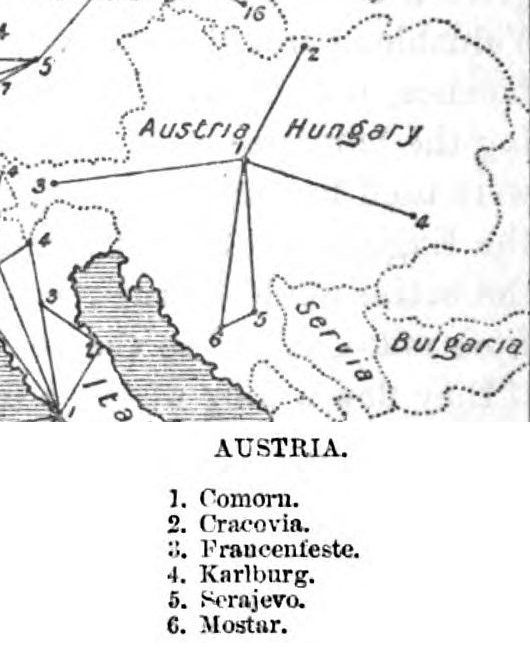

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was founded in 1867, the result of a compromise between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. It entered the world stage as a Great Power, and like all the others, raced to establish a military pigeon service in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War. The first military pigeon station was established at Komorn (Komárom) in 1875. This loft served as the point from which all subsequent stations were linked. By the 1890s, stations had been built along the Empire’s borders—there were military lofts in Cracow (Krakow) in Galicia; Franzenfest in Tyrol; Karlsburg in Transylvania; Sarajevo and Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina; and Trieste in Carniola. Unofficial stations were also privately maintained by some officers. The initial focus was on providing communication services for fortresses in mountainous districts, where telegraphic or visual signaling was impossible. Through diligent training, these birds attained speeds of 1 km over short flights.

Impressed with the pigeons’ abilities to transmit despatches between forts, military officials began training the birds for other military specialties. Attention was paid to the birds’ potential for reconnaissance work. In 1905, the Army planned a series of maneuvers in which these skills would be tested. Several non-commissioned officers were assigned to reconnoitering patrols or scouting units in the Enns–Amstetten–Haag zone and tasked with relaying important information to Linz, where the despatches would be reviewed and telegraphed to the appropriate destination. “Each non-commissioned officer carried four pigeons in a small square cage fixed to the end of a bamboo stick, which was itself placed in a sort of socket fixed to the stirrup,” one military journal recounted. Good results were achieved through these exercises, yet some of the pigeons “suffered from great fatigue caused by the long confinement in such a restricted space.”

The Army’s balloon section also experimented with pigeons, thanks to the generosity of a private breeder who offered his birds to the unit annually. The birds were taken up in the balloons and released whenever the pilot wished to communicate with officials on the ground. In contrast to similar attempts in other countries, the pigeons had a high success rate. Losses weren’t uncommon, however. During a balloon release on June 20, 1899, half of the pigeons failed to return, though three returned after nine months, one of which still bore a despatch.

The Austro-Hungarian Navy had a pigeon loft at Pola (Pula) in modern-day Croatia. Housing 120 birds, the naval station trained them for service along the Adriatic Sea, attaining distances of over 250 miles away from the home loft. In 1889, the Empress took one of these birds on a trip to Pola to Corfu, Greece, releasing it with a message for her daughter, the Archduchess. Unfortunately, a peasant shot the bird. This led to calls for laws to protect the Empire’s homing pigeons from shooting.

As the Service expanded, the military considered reaching out to civilians to bear the cost and time for training pigeons for military service. Pigeon rearing, however, had never really taken off in Austria-Hungary. Only a few associations existed and these groups didn’t possess many birds. The government tried to cultivate an interest by awarding prizes for races in Vienna and other cities, but the prize money was a rather insignificant amount. Free wood for building lofts was also provided by the government to officers and government employees who agreed to raise pigeons for the military’s use. Railroad companies joined in, offering reduced fares for those taking pigeons on long-distance training flights. In spite of these efforts, pigeon fancy remained a rich man’s pastime in the Empire.

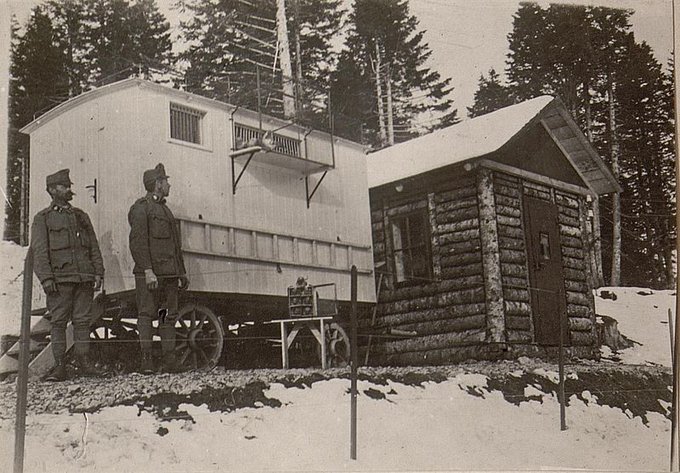

When the Great War broke out, Austro-Hungarian soldiers carried their birds with them into battle. Early on, pigeons came to the aid of soldiers defending the Galician city of Przemysl against the Russians, allowing for contact to be maintained with Vienna throughout the fall of 1914. Aside from conveying despatches, pigeons were also used for espionage. In 1915, the Italian government seized the Albanian ship La Bella Scutarina off the coast of Bari on charges that the crew were involved in a spy ring. Evidently, the Albanian crew, traveling under the cover of a neutral vessel, was collecting intelligence on Italian positions in the Adriatic Sea and sending the info back to Austro-Hungarian officials via pigeons. By the final years of the War, the Austro-Hungarian Pigeon Service had embraced many of the innovations developed during the conflict—pigeons were transported in mobile coops and even had special cages to protect them from gas attacks.

The challenges brought on by the Great War amplified pre-existing tensions within the multi-ethnic Empire. On October 31, 1918, Austria and Hungary dissolved their union. Two weeks later, the War ended. The Dual Monarchy had lasted for 51 years, just eight years longer than its Pigeon Service. All that remains these days is a former station in Trebinje, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Run by the Museum of Herzegovina, it has hosted workshops for local children, teaching them of the role pigeons played in the city’s imperial past.

Sources:

- “Albanians Sentenced for Aiding Austrians,” Asheville Gazette-News, Sept. 3, 1915, at 1.

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 129-130 (1888).

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 237 (1901).

- Department of Marine, “Report on Messenger Pigeons,” Twenty-Third Annual Report of the Department of Marine, for the Fiscal Year Ended 30th June, 1890, at 206.

- “Message from Przemysl by Pigeon Post,” The Charlotte News, Nov. 28, 1914, at 6.

- Niblack, Albert, “Naval Signaling,” The Proceedings of the Naval Institute, Vol. 18/4/64, 1892, at 454.

- “Sundries,” The United Service Magazine, Vol. 32, Oct 1905 – Mar. 1906, at 486.

- “The Sad Fate of an Empress’s Carrier-Pigeon,” The Star, Nov. 16, 1889, at 2.

-

Pigeon POWs of the Great War

To the victor go the spoils. That pithy phrase has justified the wholesale seizure of property during wartime for millennia. Throughout the Great War, both the Allies and the Central Powers confiscated military equipment from one another when the opportunity presented itself. Trucks, ships, airplanes—each captured piece of equipment had the potential to bolster militaries depleted of resources. As emergency communication devices, pigeons were no exception.

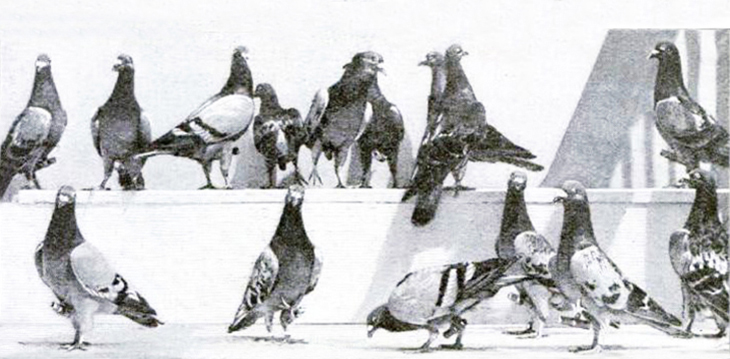

As the War turned decisively in the Allies favor in the latter half of 1918, the Germans often left their pigeons behind as they abandoned their positions. On August 9th, a Canadian regiment captured a mobile loft filled with German pigeons in Folies, France. It was turned over to the London Zoo for public viewing. Six months later, a columnist toured the former Brieftauben Station No. 708, which looked “like an old grey caravan sadly needing a coat of pain.” “Twenty or more pigeons were flying back and forth,” she reported, “excited at the intrusion of a stranger in their camp.” Zoo officials informed her that the young pigeons would soon be flying in a few weeks, while the adults were permanently grounded, since they might fly back to Germany. This fear was realized three years later when two escaped from the Zoo and flew back to Berlin.

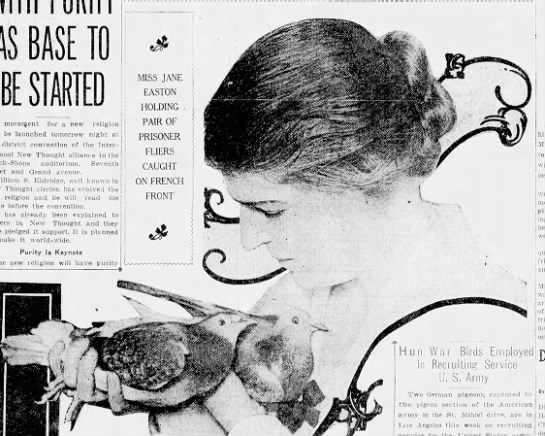

American forces, too, soon found their ranks swelling with enemy pigeons. They came across a tranche of them during the Saint-Mihiel Offensive in September 1918. Eight birds were found in an abandoned loft when the Americans captured Montsec. Two more happened to land on an American loft; they had been searching for their home lofts, which had been set ablaze by fleeing Germans. The Yanks found even more birds during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which lasted from Sept. 26 to the end of the War. While searching through a German trench, the 28th Infantry Division found a basket with 10 pigeons inside. Later on, a group stumbled across an abandoned German loft and seized the birds as they returned. In a moment of serendipity, German aviators dropped a mated pair behind American lines via parachute, hoping that their spies might find them. Instead, doughboys found them and turned them over to the intelligence department.

At least 22 pigeon POWs (if not more) sailed home with the boys in 1919. They were displayed around the country to attract potential recruits to the Army’s Pigeon Section. Afterwards, some went into private lofts, while others were donated to zoos. But the Yanks seemed to have had more pragmatic concerns on their minds than their British peers. Many of the birds were integrated into the breeding program at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, the HQ of the Army’s Pigeon Section. A POW known as the “Blue Check Frill” produced some of the Army’s best flyers—one of his sons won first place in a prominent pigeon race. At some point, unfortunately, an overly-patriotic sergeant at Fort Monmouth determined that the German birds were unfit to associate with their American peers and released a flock of them over Philadelphia. Following this debacle, in 1922, Captain Ray Delhauer—a former officer in the Section who was now employed as its Pigeon Expert—transferred several of the German pigeons to Ross Field in Arcadia, California, the Army’s breeding station for the west coast. These birds were bred to supply pigeons to the Pacific Coast and the Hawaiian and Philippine territories. Three years later, the Army closed down the Ross Field lofts, opting to use birds from civilian fanciers. Most of the remaining German birds were sent back east to Fort Monmouth.

By 1930, only a few of the German prisoners were still living in America. One passed away that year, a spoil of the Meuse-Argonne. Unlike his colleagues, this bird had not spent his years in America as a guest of the government—Frank H. Hollmann, editor of the American Pigeon Journal, had cared for him in his private loft, taking him on lecture circuits. In spite of a shrapnel wound to his eye, the bird lived for 13 years. Upon his death, he was stuffed and presented to the Missouri State Museum at the Capitol building in Jefferson City. With his death, newspapers declared that only two German birds were left in the US, both of whom were in the possession of the Army.

The newspapers were a bit off, but still close. It appears that the Army had only one German bird while two were in private custody. Captain Delhauer still had the mated pair that the Germans had kindly dropped over American lines. Given the monikers Kaiser and Fraulein, the birds were living with Delhauer at his ranch in Ontario, California. Fraulein lived until 1934, while Kaiser passed in 1937. They contributed to Delhauer’s prized Chaffey strain—a naturally camouflaged bird that was later used in World War II.

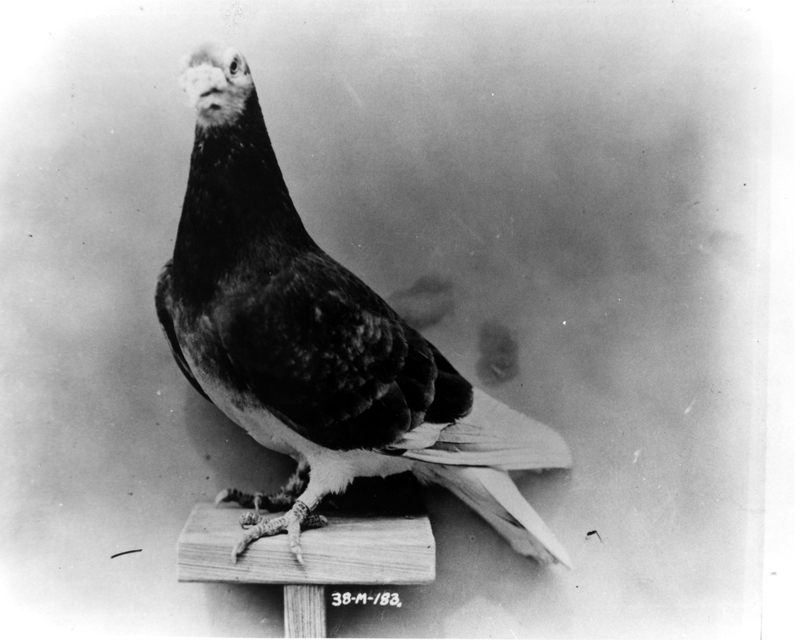

The Army’s last surviving POW pigeon—and perhaps the best known—was Kaiser. Captured by American troops in the Argonne, the bird was initially known as Rheingold, then was re-christened Wilhelm, which seems to have evolved into Kaiser by the ‘40s. Sporting a red-check coat, Kaiser was allegedly the only captured bird to come from a royal loft—in this case, the Royal Bavarian Lofts. Modern research, however, suggests that he was actually born in a private loft in Koblenz, which is in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate.

At the age of 20, Kaiser had outlived all of his fellow POWs. Given that the average life expectancy of a pigeon is 8 years, it was speculated that Kaiser would soon join his colleagues. But Kaiser showed no signs of slowing down. He continued producing champion heirs for the Army, many of whom served in World War II. In 1949, at 32 years old, he and a few veteran birds of the Second World War traveled to Washington, D.C. to witness the inauguration of President Harry Truman. On Halloween night that year, Kaiser finally died, having lived four times the normal lifespan of a pigeon. His body was stuffed and placed on display at the Smithsonian.

Although they were born in the enemy’s lofts, the pigeons captured by the Allies quickly adapted to their new homelands. They amused zoo goers, lounged around in private lofts, and even improved their host country’s military pigeon services. This resiliency is just further proof of the value pigeons add to militaries.

Sources:

- “A Canadian Woman in England,” Calgary Herald, Jan. 29, 1919, at 10.

- “Army Fosters Homing Birds,” The Los Angeles Times, Aug. 13, 1922, at 18.

- Blazich, Frank. “America’s Kaiser: How a Pigeon Served in Two World Wars.” National Museum of American History, 12 Feb. 2019, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/kaiser.

- “Famous War Pigeons to Be Taken to New Jersey,” The Pomona Progress Bulletin, Jan. 22, 1925, at 6.

- “German Pigeons Have New Home,” Altoona Tribute, Aug. 28, 1920, at 3.

- “German Pigeon, War Captive, Is Enjoying Life,” Mason Valley News, Nov. 23, 1934, at 7.

- “Hold a War Bird Exhibit,” Kansas City Star, Aug. 15, 1919, at 4.

- “Lost War Pigeons Return,” El Paso Herald, Feb. 14, 1922, at 2.

- “Only Living Captive of Germans’ Pigeons Forgets War Days,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan. 15, 1933, at 12.

- “Racing Pigeon from World War Is Dead,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Sept. 16, 1932, at 14.

- “Three Pigeons Among Great War Heroes,” The Independent-Record, Jan. 27, 1929 at 15.

- “Two Captured German Pigeons Shown in L.A.” Los Angeles Evening Express, Jun 6, 1919, at 17.

- “Warrior-Pigeon Dies,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Dec. 5, 1937, at 14.

-

Flying Incognito: Pigeons in Camouflage

One of the many innovations to come out of the Great War was camouflage. Concealment has been a wartime tactic since time immemorial, but the concept of using stylized patterns to disguise military equipment emerged in the first month of the War. Two French painters who had been mobilized into an artillery regiment hid their guns under branches and canvases painted in colors mimicking the terrain. Impressed with these and other similar efforts, the French Army established a Camouflage Section in August 1915. The Section employed painters and sculptors in workshops throughout the country to develop camouflage techniques. Teams of artists—many of whom came from the cubist tradition—created irregular patterns that could be painted onto artillery pieces, railroad equipment, trucks, and other equipment. These ideas spread and quickly became a fundamental part of modern warfare.

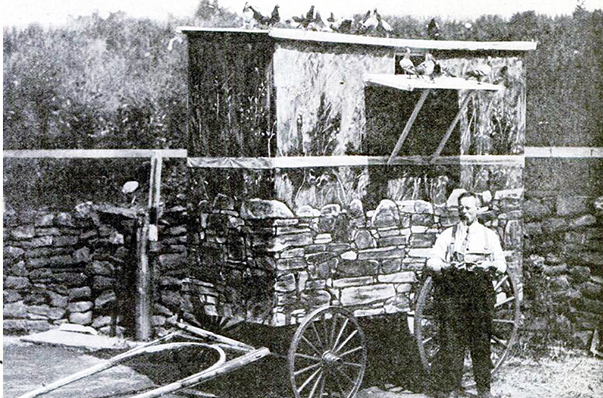

Camouflage methods were eagerly adopted by military pigeon services in both World Wars. The primary focus was hiding the pigeons’ lofts. Large and conspicuous, mobile lofts near the front line were susceptible to attacks by enemy aircraft. Stationing them near a building or under a tree helped, but that wasn’t always an option if the units were in an open field. A simple way to conceal a coop was to paint it entirely olive-drab green. For more advanced techniques, a painter could cover the coop in a melange of brown and green hues, or try to accurately reflect the natural surroundings. In one widely-circulated photograph, a mobile loft has been painstakingly painted to match a stone fence and vegetation in the background. But those tasked with concealing lofts had to be careful that their efforts didn’t confuse the birds. During preparations for the Battle of the Somme, for instance, an army of artists worked feverishly to camouflage the British Army’s equipment. Apparently, they were too good—the concealed coop was so convincing, the pigeons failed to return to their loft.

Officials also experimented with camouflaging pigeons themselves, as their bright patches of white or colored feathers and distinctive outlines made them an easy target for sharpshooters. The first recorded instance of pigeon camouflage occurred during the Battle of Verdun. As the fighting stretched on, the German Crown Prince Wilhelm grew frustrated as the French kept sending for backup with their pigeons. Tired of standing by helplessly while French pigeons flew overhead, he formed a crack battalion to put a stop to this. He recruited experienced trapshooters and equipped them with shotguns. Their task was to shoot down any pigeons spotted flying towards French HQ. As the soldiers shot down bird after the bird, the French had no choice but to camouflage their messengers. Pigeons were dyed completely black so they resembled crows. The subterfuge paid off. One of these mock crows—formerly a milky-white pullet by the name of Babette—was released from behind German lines. The bird carried a message that detailed a planned attack on the Meuse. Thanks to this despatch, Allied forces thwarted the offensive.

Subsequent attempts at camouflaging pigeons utilized the standard swatches of greenish hues. The methods of application varied by country. The British used paint, which worked out in their favor when a painted pigeon saved a regiment during the Battle of the Somme. The Americans apparently used a concoction of chemicals similar to “the drugstore ingredients which brunettes often use to make themselves blonde overnight.” The Germans tried dusting their pigeons with a green powder, but the powder broke down in light rain and caused the feathers to absorb water rapidly. Weighed down, the birds were incapable of flying.

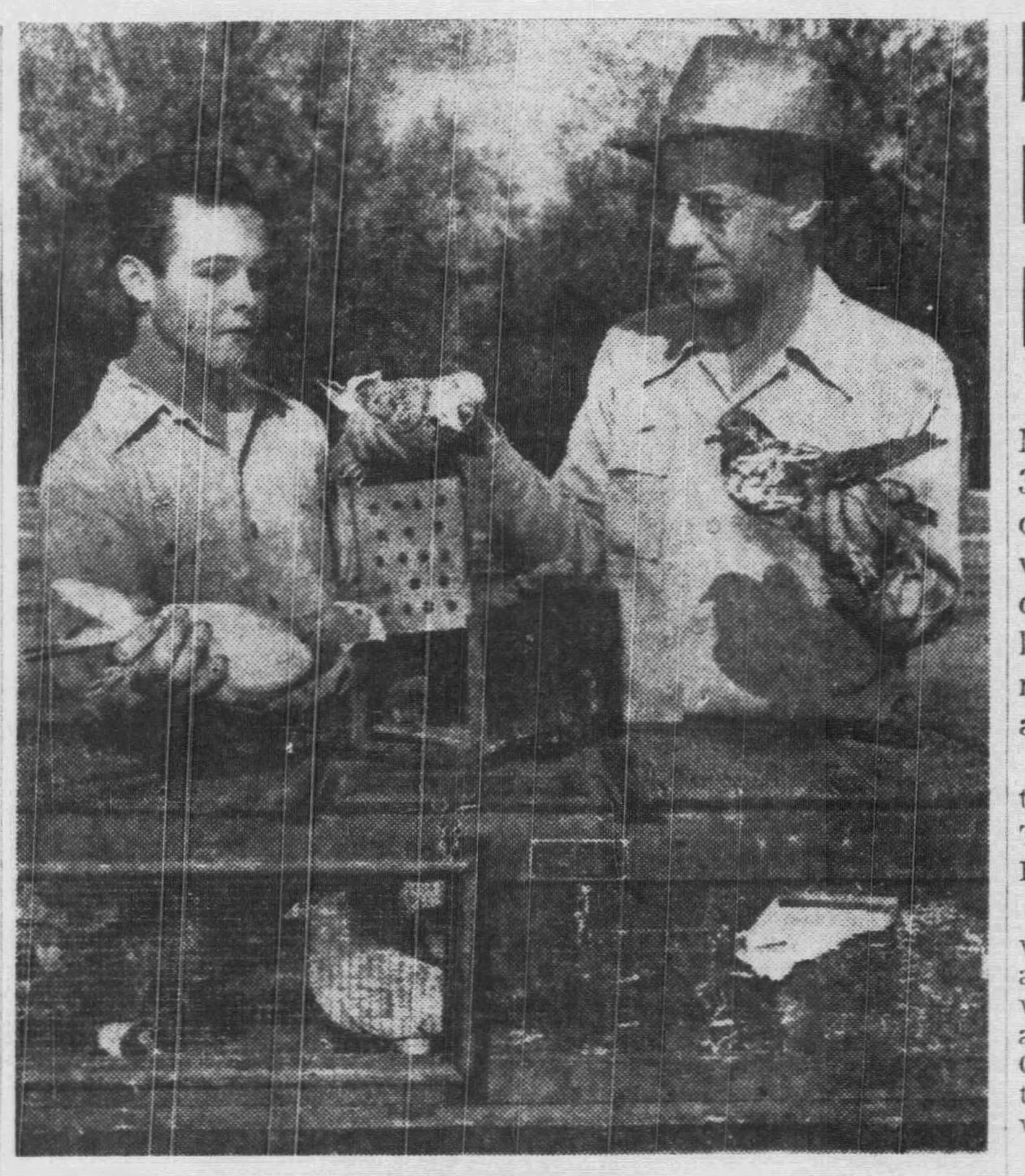

In the years leading up to America’s entry into World War II, Ray Delhauer—a former captain of the US Army Signal Corps’ Pigeon Service—took it upon himself to breed a stealthier bird. Delhauer had served in World War I, training many of the Pigeon Service’s officers and birds. By 1940, he had retired from the Army and was teaching at a high school in Ontario, California. Delhauer still had one foot in the pigeon world, though. He had formed a club for his students to breed and raise pigeons. Together, they worked to develop an elite bird that might be useful for the Army, mixing Black Bovyns—a breed suited for flights over the Swiss Alps—with grizzled veterans of the First World War. Included amongst their ancestors were Allied superstars Mocker and Spike and Germany’s Kaiser and Fraulein.

Satisfied with the birds’ performances, Delhauer and his students then shifted focus. The new goal was to make the pigeons’ coloration less perceptible. Through intense breeding and crossbreeding, Delahauer developed a half-dozen color mixtures for use in specific environments. A blue-rust variety was reportedly nearly invisible over one type of terrain, while a mottled gray-and-white strain blended in with urban skies. After the US entered World War II, the Army took an interest in Delhauer’s birds. In 1943, he shipped batches of them to Army sites in South Carolina, New Jersey, and Missouri, where they were incorporated into military breeding programs. By the end of the War, Delhauer had donated over 400 camouflaged pigeons to the Army.

Camouflage forever altered approaches to concealing military equipment. By disguising pigeons and their coops, militaries ensured that emergency communication services were readily available. Undoubtedly, many more lives were saved, thanks to the ingenuity of artists.

Sources:

- “Camouflage.” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/camouflage.

- “Camouflaged Carrier Pigeons Developed for Army Use with Aid of School Boys,” The Paterson Morning Call, Oct. 11, 1941, at 12.

- “Camouflaged Pigeons Displayed at Ontario,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Apr. 11, 1943, at 13.

- “Death Claims Pigeon,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Aug. 8, 1948, at 19.

- March, Eva, The Little Book of the War, at 76 (1918).

- Naether, Carl, The Book of the Racing Pigeon, at 58 (1950).

- “Pigeons Are Bred with Camouflage for War Service,” Popular Mechanics, Vol. 138, No. 1, January 1941, at 81.

- “Pigeons Camouflaged to Escape Teuton Snipers,” Lansing State Journal, May 6, 1918, at 10.

- “Pigeons Prepared for Easter Sunrise,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Apr. 5, 1939, at 14.

- “Saves Regiment,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, Nov. 19, 1917, at 3.

- “School Gives 200 Birds to Army Pigeon Center,” The Los Angeles Times, Nov. 29, 1943, at 10.

- The United States Army, The Pigeoneer, at 86 (1924).

- “They Winged Their Way Through Skies of Steel,” The American Legion Weekly, Vol. 1, No. 9, Aug. 29, 1919, at 16-18.

- “Train in France,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, Nov. 19, 1917, at 3.

-

War Birds on Stage

Military pigeons have frequently inspired creators. That’s not surprising—their heroic deliveries of important battlefield dispatches amidst torrents of gunfire are ripe for artistic endeavors. Cher Ami’s transmission of the message that saved hundreds of American soldiers is portrayed in the 2001 film The Lost Battalion. The BBC sitcom Blackadder humously depicted the consequences of shooting a military pigeon. The video game Battlefield 1 allows the player to control a pigeon as it carries a message from a tank crew in distress.

But what about theater? Has anyone ever mounted a production featuring war birds?

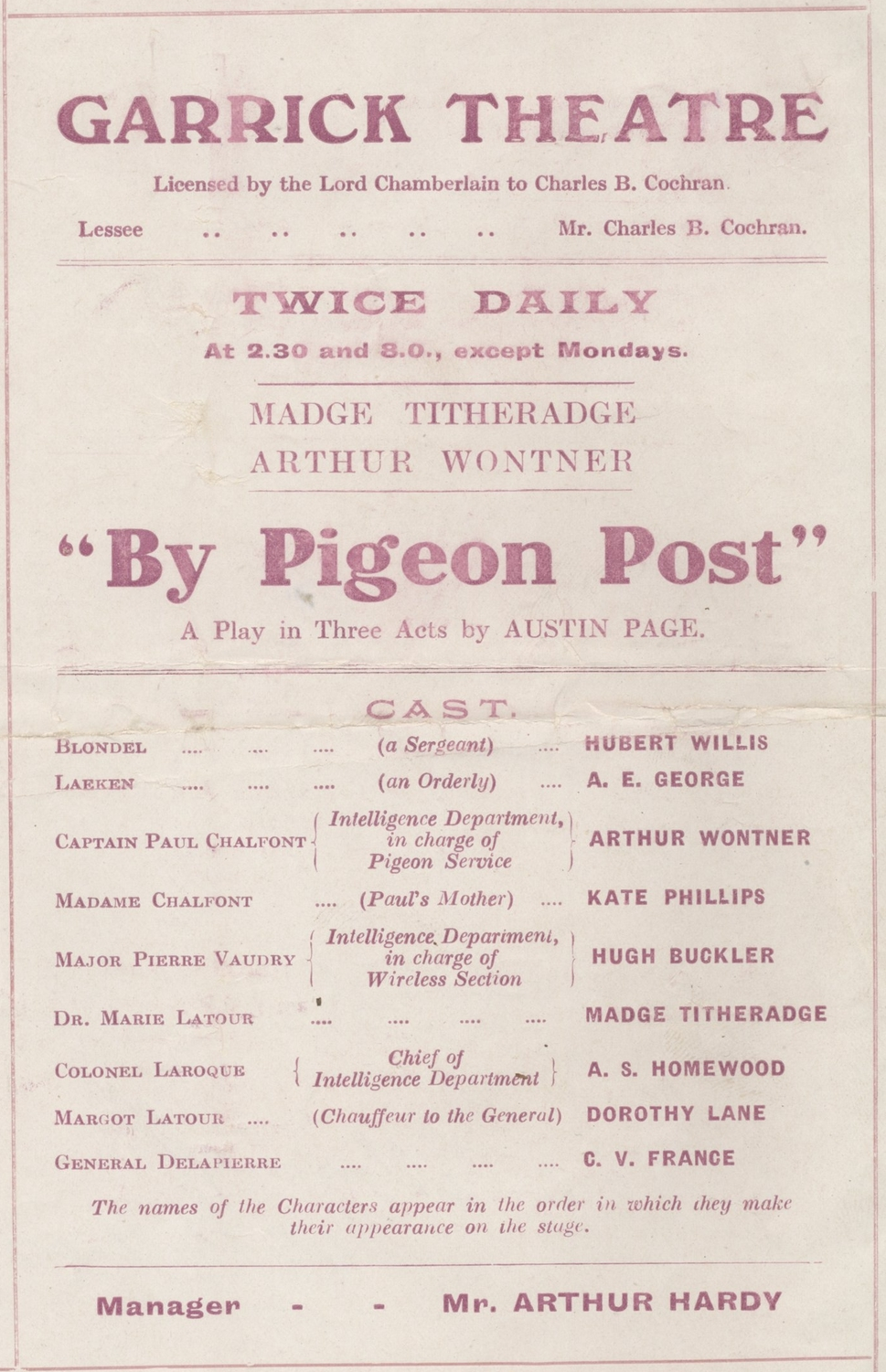

In the final year of the Great War, playwright Seymour Obermer completed By Pigeon Post, a play revolving around military pigeons. Born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1867, he moved to the United Kingdom as a young man and became an importer of American automobiles. At some point in the 1900s, the theater bug bit Oberme and he began writing plays. He wrote two under his own name before adopting the nom de plume Austin Page for his subsequent works.

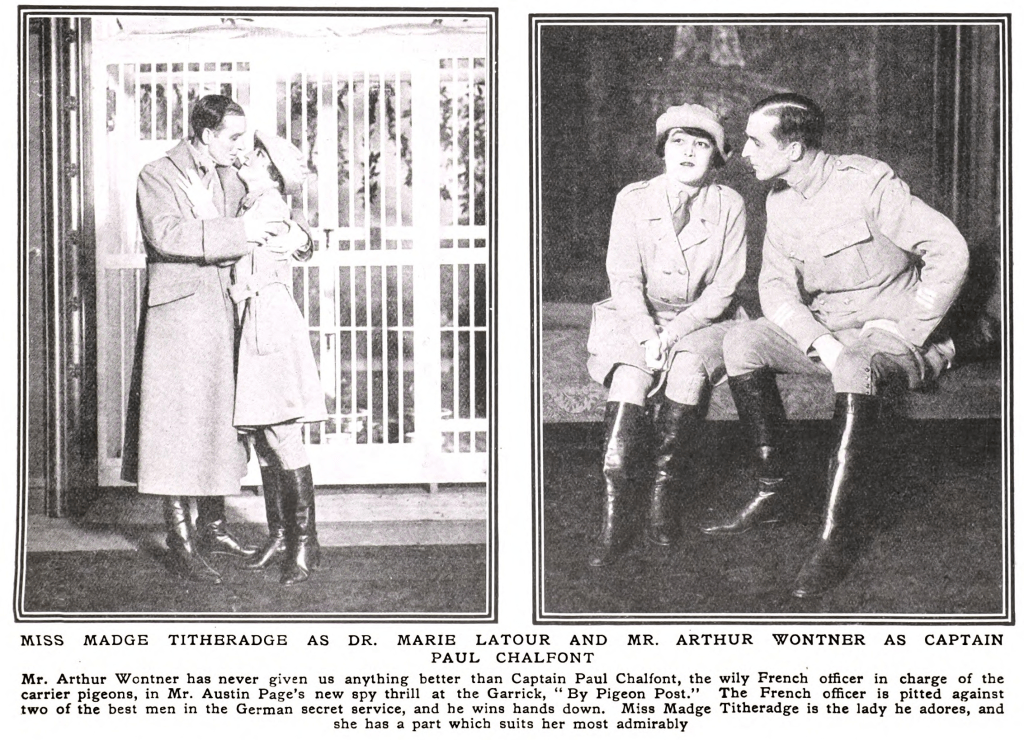

Oberme’s play was the latest in a series of melodramatic spy plays that emerged during the Great War. We have not been able to find an actual copy of the script. Still, a summary of the play can be reconstructed from various sources. The setting is French Lorraine, around 20 miles away from the front. The scenes take place in the library of a chateau that has been converted into an intelligence office; it includes both a pigeon loft and wireless station. The characters are all members of the French Army. Captain Paul Chalfont, the play’s protagonist, is the head of the French Army’s Pigeon Service. He is anxiously awaiting the arrival of a pigeon sent from behind German lines with information about a forthcoming plan of attack. Major Pierre Vaudry, the cantankerous head of the Wireless Section, is the play’s villain; he is actually a German spy working with his orderly Laeken, a secret German citizen posing as a Fleming. Marie Latour, an Army doctor, is the heroine of the play—both Paul and Pierre are in love with her.

In Act I, Pierre and Laeken interfere with Paul’s pigeons, making the Service look ineffective to his superiors. Paul, distressed that his bird has yet to arrive, volunteers to cross the German lines in disguise and search for the pigeon. Laeken eagerly agrees to accompany Paul on his quest. Act II commences with Laeken and Paul’s return, where it appears that Paul is suffering memory loss from shell shock. It is revealed that Laeken actually struck Paul on the head with the butt of his rifle to steal secret plans the Captain was carrying. Laeken discovered the plans were fake, so he brought the Captain back to the chateau, attributing his memory loss to shell shock. Paul is faking his symptoms, however, and with the help of Marie, has Laeken and Pierre charged with spying. In Act III, Paul’s pigeon returns to the chateau with the needed information, redeeming the Service. The spies are tried for treason and convicted—Pierre commits suicide by jumping off a high tower, while Laeken is shot. Amidst the drama, a comedic subplot is present involving a French General’s love for his driver, who happens to be Marie’s sister.

To add a touch of realism, the script called for 20 live homing pigeons to be featured in the chateau’s aviary. The idea was to give people a glimpse of a functioning pigeon service. Over the course of the play, audiences would see several pigeons arrive on stage with messages and others being fitted with dispatches for delivery.

Like all productions of the wartime period, the script had to be submitted to the British authorities for review. The censors left most of the play intact, but struck the script’s direction to include the sound of gunfire at the end of Act II. “This is quite unnecessary to the play and on an air raid night might quite possibly be alarming,” one censor chided.

By Pigeon Post debuted at the Garrick Theatre in London on March 30, 1918. Among the actors starring in it was Arthur Wontner, who would go on to play Sherlock Holmes in a series of films in the ‘30s. It was a smash hit with audiences throughout the United Kingdom. Queen Mary viewed it and said it was the best play she’d seen in years. By the time the show ended in 1920, nearly 400 productions had been staged.

While it was running in London, Oberme traveled to America to shop around his play. Several producers were interested in the script, but balked at the price. The Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld, however, liked the play and paid the asking price of $7,000; “A few thousand dollars more or less mean little in this manager’s life,” a theater magazine remarked wryly. Long known for his light-hearted Ziegfeld Follies, this would be his first drama.

Ziegfeld’s production of the play debuted on Broadway exactly two weeks after the War had ended. American audiences were less than enthralled with the show. Critics felt that the story had lost much of its emotional force now that troops would soon be returning home. Indeed, for many playgoers, the pigeons on stage were the best part: “The pigeons themselves are very good and sympathetic. Their cooing and fluttering in a cage give the production its chief interest,” declared a critic. The show ended after a nearly three week run.

In the years since, the play has been entirely forgotten. The last production was in 1940 at the Garrick, when Britain found itself once again at War with Germany. Modern audiences would likely find it to be hopelessly dated, as tastes have soured on melodramas. Nonetheless, a timely theme is present throughout—the clash between technology and nature. It’s significant that the villain of the play is in charge of the military’s wireless service. His way represents the modern method of sending messages, using machinery to communicate through the airwaves. Relying solely on animal power, Paul’s pigeon post is a relic of a bygone era. Yet, it is only through sabotage that Paul’s pigeons fail, and, in the end, they prove triumphant. This has remained a powerful theme in film and television to this day.

We at Pigeons of War would love to see a modern performance. Any readers interested in mounting a production?

Sources:

- “A New and Thrilling Spy Play,” The Tatler, Vol. 68, No. 877, April 1918, at 61.

- “By Pigeon Post.” Great War Theatre,https://www.greatwartheatre.org.uk/db/script/2465/.

- “‘By Pigeon Post,’” The Looker-on, Feb. 22, 1919, at 15.

- “‘By Pigeon Post’ at Cohan Theater,” The Standard Union, Nov. 26, 1918, at 5.

- “‘By Pigeon Post,’ at the Garrick Theatre,” The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, Vol. 89, Apr. 27, 1918, at 234.

- Darnton, Charles, “‘‘By Pigeon Post’ Fails to Carry,” The Evening World, Dec. 5, 1918, at 5.

- Maunder, Andrew, British Literature of World War I, Vol. 5, at xciv (2011).

- “Next Week — ‘By Pigeon Post,’” Folkestone, Hythe, Sandgate and Cheriton Herald, Aug. 31, 1918, at 16.

- “What’s What in the Theater,” The Green Book, Vol. 21, No. 1, Jan. 1919, at 30.

-

Old Satchelback: The Loveable Loser

They got a name for the winners in the world

And I want a name when I lose

They call Alabama the Crimson Tide

Call me Deacon Blues

The jazz-rock group Steely Dan celebrated dignified loserdom in their 1977 song “Deacon Blues.” As the above passage suggests, the song’s protagonist—a hapless daydreamer—wants to be remembered in spite of his failures. In the annals of military pigeon history, only the winners are remembered. Subjects of books, poems and even film, these pigeons achieved fame by delivering messages at great peril to themselves. They are often bestowed with grandiose names in recognition of their valor—Cheri Ami, President Wilson, Lord Adelaide, Lady Ethel, to name a few.

For every war pigeon that enters the history books, there are hundreds of thousands—if not millions— that are unknown to the public. Some of these pigeons were merely adequate at their jobs or never had the opportunity to deliver a message of real significance. Many, however, were simply lousy homing pigeons. You won’t find any poems written about them. Why would anyone want to commemorate a bird that couldn’t even do its job?

Arguably, at least some of these so-called losers have been unfairly consigned to the dustbin of history. Even though they lacked the chops for wartime service, maybe these birds had other talents that’ve been overlooked. Take Old Satchelback, for example.

Old Satchelback served in the US Army Signal Corps during the final months of the Great War. Early on, his trainers realized that the pigeon was not a top-tier athlete. “He isn’t what may be called a good bird,” declared one newspaper article. Nor was he “as fast on the wing” as the other birds in his loft. In fact, Old Satchelback was regarded as “one of the laziest birds in the A.E.F.” because of his failure to take flying seriously. Entrusted with the transmission of vital information, Old Satchelback didn’t see the need for a rapid delivery. Flying for long stretches tired him out, so he frequently cut flights short and walked the rest of the way back. Given that pigeons are incapable of walking more than 2 miles an hour, Old Satchelback’s leisurely strolls were a very inefficient way of delivering urgent messages from the front.

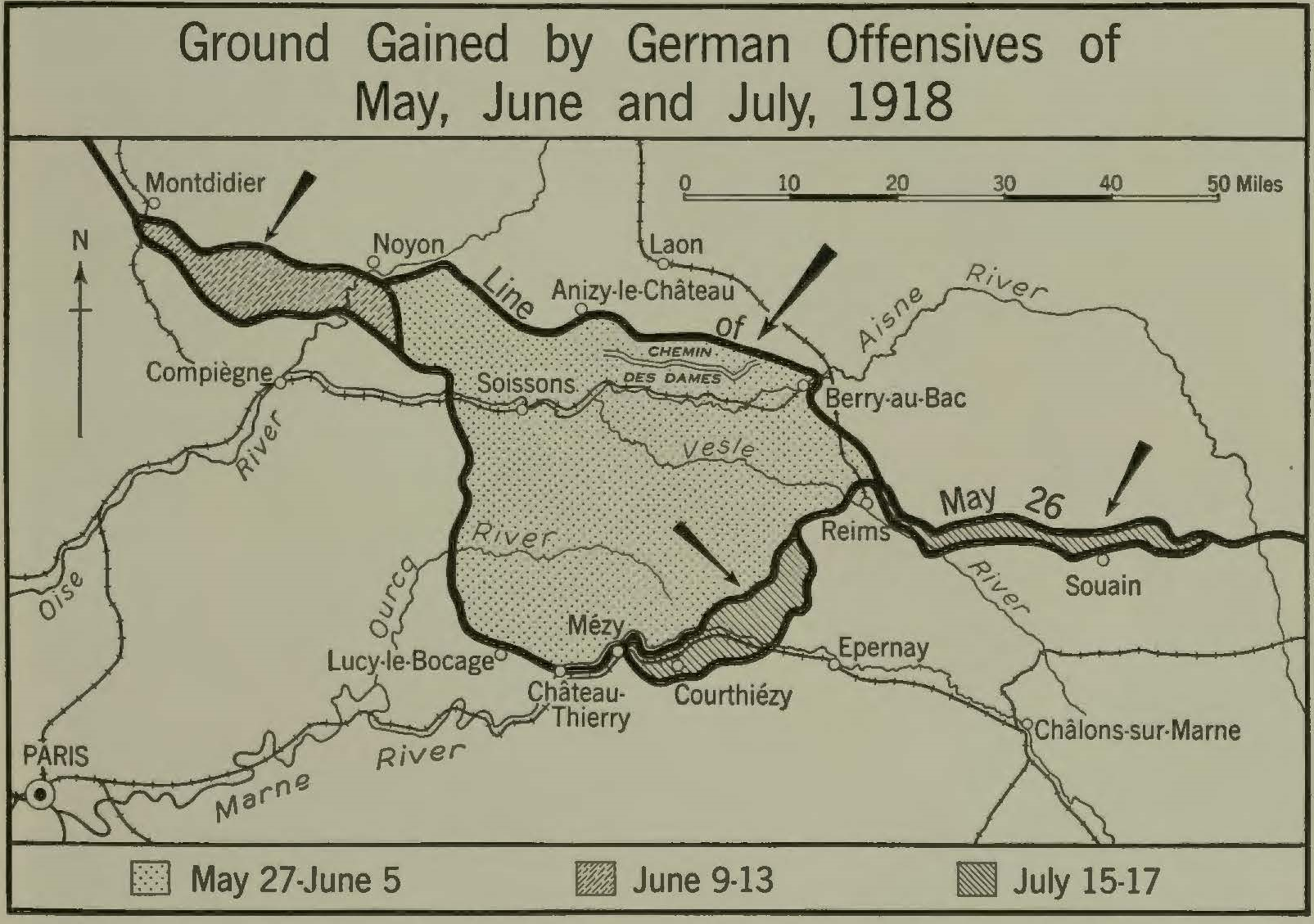

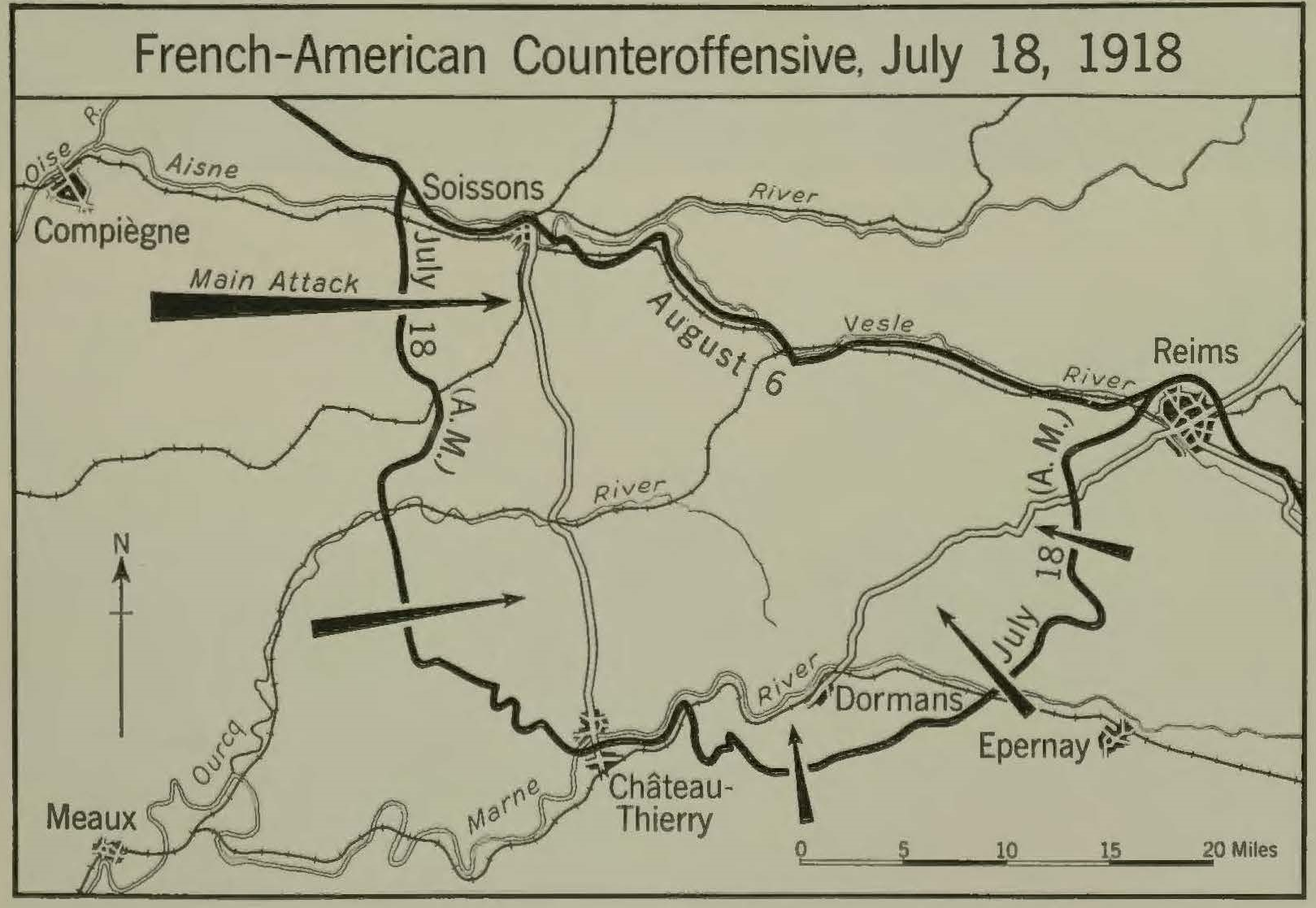

Old Satchelback’s laziness reached epic proportions at the Vesle Front in northeastern France. Throughout July and August 1918, Allied forces pushed German troops out of the Marne Salient and back past the Vesle River. In early August, three American divisions were stationed along the Vesle, tasked with keeping the Germans from crossing the River. The Vesle Front was the site of fierce fighting for nearly a month—the Battle of Fismes and Fismette, for instance, involved street fighting and flamethrower attacks.

Amidst this maelstrom of violence, Old Satchelback was taken to the Front for some unknown reason and released with a message for HQ. True to his nature, the bird soon tired of flying and sought out a road. He spotted one and landed. As he scampered down the path, he stumbled across a section that was pockmarked with shell craters. A normal pigeon encountering such an obstacle probably would’ve taken flight. But Old Satchelback was no ordinary pigeon. Observing that engineers were busily filling in the holes, he hunkered down and patiently waited for the crew to finish the job. “Then he strutted majestically over the new made highway,” the awestruck engineers reported to their colleagues. The audacity of this bird must be admired

After his jaunty saunter along the Vesle, Old Satchelback’s superiors grounded all future flights and confined him to the coop permanently. Such a lackadaisical attitude toward flying typically would be grounds for culling. Yet something about Old Satchelback delighted his superiors. He was “a constant source of amusement” to them, possessing a “genial” temperament. His loft mates were likewise captivated by his attitude toward life. Recognizing the bird’s influence amongst his peers, Old Satchelback’s trainers recruited him for a special task: escorting shell-shocked pigeons back to the coop. The constant barrage of shellfire often upset the birds as they flew back to HQ. Whenever one arrived at the coop, it was common for the pigeon to circle nervously over it repeatedly without entering. This delayed officials from reading important battlefield dispatches, putting hundreds of soldiers’ lives at risk. Old Satchelback would be released at this point and join his companion in the air. Circling around the bird, he would then lead it back to the loft. If the pigeon failed to follow, Old Satchelback would try again repeatedly until it returned home. By the second or third attempt, the pigeon almost always tagged along.

Old Satchelback didn’t save hundreds of lives like Cher Ami. Unlike Lady Ethel, he was neither exceptionally fast nor dependable. He could barely do his job. Nevertheless, he brought joy to his commanders and comfort to traumatized pigeons. We at Pigeons of War believe this qualifies him for inclusion in the history books.

Sources:

- “France Gives Birds Pension,” The Bend Bulletin, Oct. 22, 1918, at 4.

- “They Winged Their Way Through Skies of Steel,” The American Legion Weekly, Vol. 1, No. 9, Aug. 29, 1919, at 30.

-

The Imperial German Navy’s Pigeon Service: 1876 – 1918 A.D.

We here at Pigeon of War often mention the Franco-Prussian War in our posts. It’s an important moment in military pigeon history. By showing the world that homing pigeons could deliver messages in wartime, it led to a pigeon arms race all across Europe. However, another significant event occurred during that War—the birth of the German Empire. On January 18, 1871, German princes and military officials gathered in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles and proclaimed Prussian King Wilhelm I the Emperor of the German Empire. For the first time since the Congress of Vienna, the balance of power in Europe had shifted.

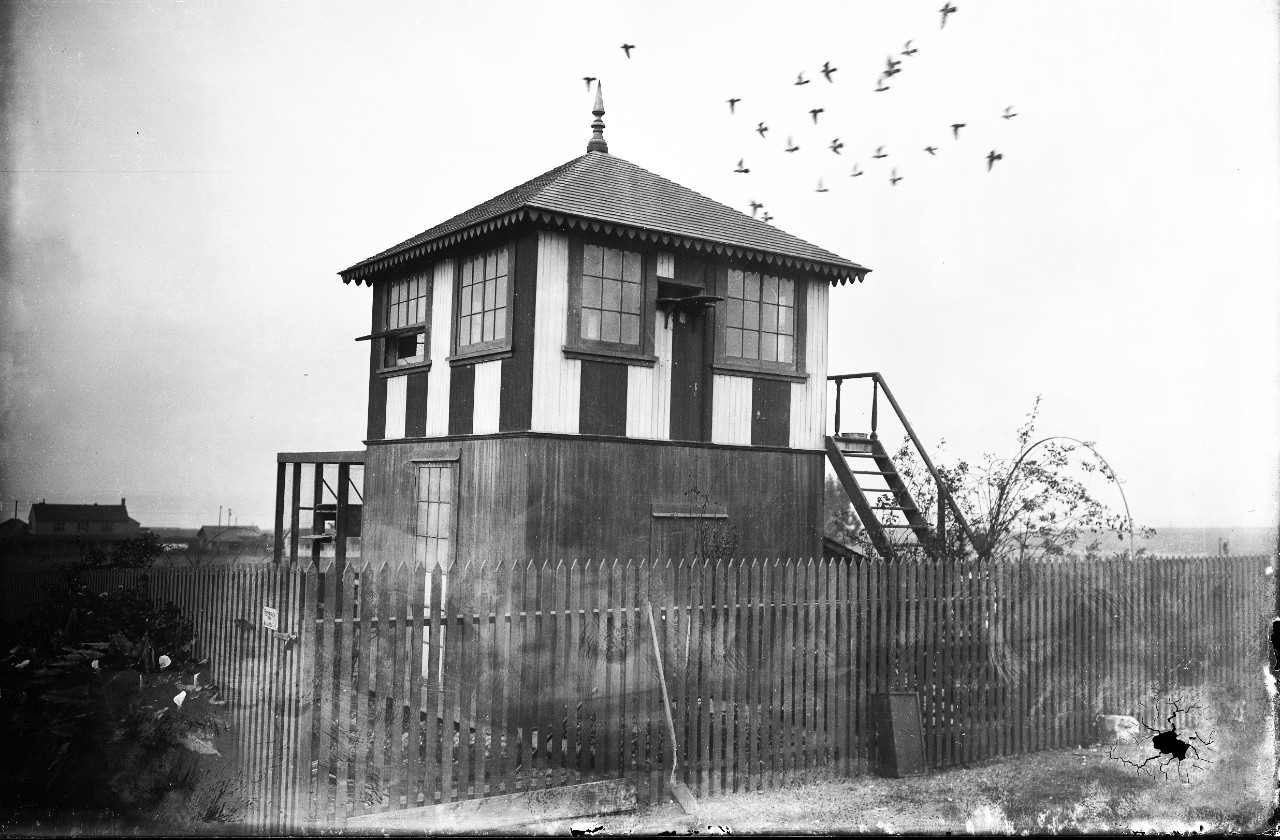

With its Northern coast encompassing the North and Baltic seas, the newly founded Empire set to work improving the tiny navy it had inherited from its predecessor. An immediate concern was communication between ships at sea and the shore. Inspired by the success of Paris’ pigeon post, naval officials began experimenting with pigeons in 1876. This initial foray sought to establish communication with light-ships stationed off the coast of the North Sea. The port city of Tönning, located on the mouth of the Eider River, contributed a flock of birds to the light-ships Eidergaliote and Außeneider. The birds proved to be effective communicators, delivering news to port authorities of incoming ships, requests from captains, and emergency situations. These deliveries are all the more impressive considering the birds regularly confronted severe gales blowing off the Eider River.

Impressed with these results, in 1882, the Imperial Admiralty decided to establish a naval pigeon service. To ensure a constant flow of communication across two seas, naval officials organized the coast into several carrier pigeon districts. Each district was 190 miles (305 kilometers) long, the maximum distance a pigeon could fly. The Baltic Sea had two districts, with pigeon stations in Danzig (Gdansk) and Friedrichsort. The North Sea had five districts, with pigeon stations in Cuxhaven, Heligoland, and Wilhelmshaven. After considerable training, the birds attained speeds of 62.5 miles per hour (100.5 kph). Although mostly used for ship-to-shore communication, some pigeons were trained for shore-to-ship communication.

Kaiser Wilhelm II took a personal interest in all things Navy-related, and pigeons were no exception. While vacationing on his yacht the Hohenzollern, he sent messages to the mainland via pigeons. To promote pigeon rearing in Germany, he sponsored fancier groups. Approximately 61 of these groups agreed to provide their birds to the Navy. They set up their own stations at Kiel, Lubeck, Rendsburg, Nortorf, Hamburg, Bremen, and near Dusseldorf and Crefeld. The Navy paid fanciers the costs of transporting the birds to the place of embarkment and for care while aboard ships. This freed the Navy from having to care for thousands of pigeons. The Kaiser recognized the sacrifices made by these fanciers by awarding them medals throughout the years.

A set of standardized procedures was developed to ensure successful transmission. Duplicates of each message were required to be sent. For distances up to 50 miles, a pair of pigeons were released, while 3 to 5 traveled together at distances of 50 to 190 miles. The ship retained a copy of each message sent as well. Messages were written onto gelatin paper and inserted into an india rubber case and glued shut. The case was then secured to a pigeon’s foot with a rubber ring. The manner in which messages were processed depended upon who owned the bird. Messages carried by the Navy’s birds were turned over to the central information bureau of the station in question. Messages carried by private birds were sent to the proper commandant, who would forward them via mail or telegraph.

All warships—with the exception of torpedo boats—were required to travel with pigeons when embarking from Kiel or Wilhelmshaven. This was to ensure that naval personnel had experience handling the birds. The fleet also deployed thousands of birds each year during its annual maneuvers. Sailors were allowed to use the birds to send private letters to the mainland, provided that the message included stamps for delivery by mail.

The advent of wireless telegraphy, however, threatened the Navy’s pigeon post, as officials eagerly embraced the new technology. In 1909, the German Colombophile Societies held a meeting in Frankfurt, inviting naval representatives to attend. The fanciers tried to convince them that pigeons still had a lot to offer the Navy, regardless of technological advances. The meeting had little impact on them—The pigeon service was officially dissolved that year.

Yet, the Great War showed that wireless wasn’t always reliable or even feasible. In recognition of this, the Navy revived its pigeon program to supply submarines and seaplanes with birds. In the event radio communications failed, the pigeons allowed for contact to be maintained with naval bases.

With the end of the War, the German Empire crumbled. The Navy and its pigeon post likewise folded. This was the end of Germany’s naval pigeon service; neither the Reichsmarine nor the Kriegsmarine implemented one in subsequent years. It’s a shame the Navy’s pigeons don’t receive much acclaim. For nearly 40 years, they greatly enhanced maritime communication throughout the Empire, no easy feat in an era before electronic communication. That is an achievement worth celebrating.Sources:

- Brieftaubenstation Tönning – Eiderstedter Kultursaison, https://eiderstedter–kultursaison-de.translate.goog/ueberblick/toenning/brieftaubenstation-tonning?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc.

- Carrier Pigeons,” The Journal of the Royal Defence Institute, Vol. No. 53, January to June 1909, at 240.

- “Carrier Pigeon Stations of the German Navy,” The Baltimore Sun, May 11, 1903, at 10.

- “Carrier Pigeons in Warfare,” The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art, Vol. 36, No. 2, Aug. 1882, at 289.

- Marion, Henri, “Homing Pigeons for Sea Service,” The Proceedings of the Naval Institute, Vo. 19, Jul 1896, at 649-650.

- “Medaillen Für Brieftauben.” Geschichte Der Brieftaube – Historie Der Brieftaube, https://www-brieftauben–historiker-de.translate.goog/brieftaube/medaillen/?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp.

- Wainwright, Richard, “Naval Coast Signals,” The Proceedings of the Naval Institute, Vol. 15/1/48, Jan. 1889, at 71-72.

- War Department, “The Carrier Pigeon Service on the Coasts of Germany,” Bulletin of Military Notes No. 1, Dec. 31, 1903.

-

Happy Jack: The Pigeon of Mons?

Cher Ami. GI Joe. President Wilson. These are among the most celebrated homing pigeons of the more than one million that served in both World Wars. But what about all the others? This is the first part in an occasional series that examines lesser-known war pigeons.

On August 23rd, 1914, the British Expeditionary Force and the German Army squared off at the Belgian city of Mons. It was their first engagement in the Great War. French authorities had tasked the BEF with guarding the left flank of the Fifth French Army from advancing German forces. Although outnumbered by about 2:1, the BEF dug into the Mons-Condé Canal and attempted to halt the German 1st Army. Britain’s experienced, professional soldiers inflicted disproportionate losses on the German, but after 48 hours, the British were forced to retreat.

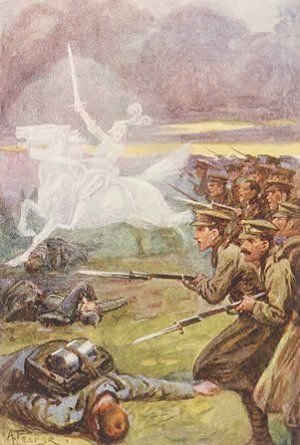

Technically a loss for the BEF, the Battle of Mons nonetheless boosted the spirits of the British public. It also stimulated their imaginations—within weeks, an elaborate mythology had begun to take shape. On September 29th, Welsh author Arthur Machen published a short story in which ghostly bowmen from the Battle of Agincourt, having been summoned by British soldiers retreating from Mons, come to the aid of their countrymen. Some readers thought Machen’s story was factual, as it was written like an eyewitness account. Variations of the tale started appearing in magazines, newspapers, and pamphlets around the country. By mid-1915, these retellings featured angelic warriors, strange, luminous clouds, and all sorts of other supernatural manifestations. Known collectively as the Angels of Mons, the stories comforted British society—they were proof that God was on the side of the Allied cause.

An equally legendary, yet more mundane account from the Battle of Mons credits a Belgian Homer named Happy Jack with saving dozens of lives. As the story goes, a detachment of 70 troops found themselves cut off from the main body by the Germans. The soldiers attached a message to Happy Jack and released him. The message was delivered, bringing relief to the soldiers. Happy Jack was declared a hero by the 70 men he saved. He served with the BEF throughout the rest of the War “and escaped without a scratch.”

It’s a great story and much more believable than angelic warriors descending from the Heavens to vanquish the Hun. But was Happy Jack—the Pigeon of Mons—actually at Mons? It’s hard to say conclusively, but the narrative seemingly crumples under scrutiny. The BEF didn’t have a pigeon service when it landed on the continent, for instance. French authorities sent a batch of birds to the British HQ nearly three weeks after the battle on September 11th, but the British Pigeon Service wouldn’t exist until 1915. If the British had pigeons at the Battle of Mons, they would’ve had to have been donated by Belgian fanciers.

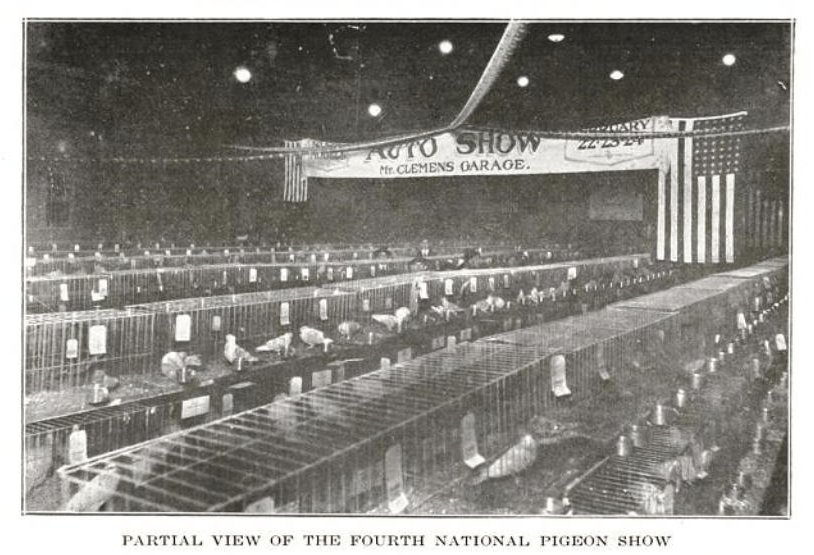

More significantly, no accounts of the pigeon’s heroic deed ever appeared in British media during the War. In fact, Happy Jack’s story doesn’t appear in print at all until nearly a decade later. In January 1923, multiple American newspapers reported that the bird had saved 70 lives during the World War. Some of the accounts mention his presence at the Battle of Mons, others don’t. They all, however, note that he had just been sold to an American fancier and would be the chief attraction at the upcoming National Pigeon Association’s show in Michigan. One can’t help but suspect that the show’s organizers were trying to gin up some good PR for the event by trumping up the wartime credentials of a pigeon that may or may not have served in the Great War. Evidently, it worked, as the American Pigeon Journal observed that “he was quite an attraction at the show.”

Alas, Happy Jack probably didn’t serve at Mons. His story, like those of the phantasmic fighters, forms a part of the mythos surrounding the battle. If anything, it adds a touch of realism—there are many examples of pigeons saving units from destruction later on in the War. At the same time, it plays off the narrative that miraculous forces intervened to save the British Army from utter annihilation. Regardless of whether it happened or not, the story of the Pigeon of Mons is a fascinating glimpse into how folklore evolves to meet the needs of its audiences.

Sources:

- “Happy Jack,” Mon’s Hero, Sold,” The Lansing State Journal, Jan. 18, 1923, at 1.

- Holleman, Frank, “Fourth National Pigeon Show and Convention,” American Pigeon Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, Feb. 1923, at 52.

- “70 Soldiers Owe Lives to ‘Happy Jack’ a Pigeon,” The Tribune, Jan. 19, 1923, at 1.

-

Pigeons vs. Radio

Pigeons and radio—their relationship is complicated, to say the least. Before radio—or wireless telegraphy, as it was initially known—first burst onto the scene, few methods of reliable, long-distance communication were available in areas unsuited for telegraph cables, such as the sea or mountainous terrain. Outside of sending a mounted rider or dispatch vessel, those wanting to send a message had to make due with flags or loud noises, balloons or pigeons. The first three had visibility limits of 10 miles (16 kilometers), while pigeons could deliver a message from 150 miles (241 kilometers) away at 25 to 40 mph. Clearly, a pigeon service was the superior medium for communicating with remote or inhospitable locations.

That all changed in the summer of 1898. On July 21-22, Guglielmo Marconi set up his wireless telegraph system aboard a steamer and broadcasted in real-time the results of the annual Kingstown Regatta yacht races. It didn’t take long for prognosticators to declare the imminent death of the pigeon post. The benefits were obvious. Wireless offered two-way communication. Wireless didn’t need to be fed or watered. It could be used at night. It didn’t have any natural predators.

Navies quickly gravitated toward wireless telegraphy. With wireless systems, ships could communicate with the shore or ships at sea. As a consequence, naval officials rushed to disband their pigeon services. In 1901, the US Navy shut down its pigeon service in favor of wireless. The old pigeon coop at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Northern California was converted to a radio shack by 1904. The British and German navies would follow suit in 1908 and 1909.

Armies weren’t so quick to jettison their pigeons. At the outset of the Great War, the majority of the belligerents maintained pigeon services and would continue to do so throughout the conflict. That’s not to say they weren’t eager to deploy their new wireless units in battle. Indeed, the German Army invested heavily in the new technology, supplying every Army HQ and cavalry division with sets. But issues they encountered prompted them to keep pigeons available for backup.

An initial concern was the general scarcity of wireless sets. As it was a relatively new technology, most armies possessed only a handful. When the British Expeditionary Force landed in France in August 1914, for instance, it had only one portable set crammed into the back of a truck. A month later, the BEF had just ten units. Even as armies purchased more sets, it still was a very specialized piece of equipment that could be assembled by only just a few companies in the world. Pigeons, in contrast, were plentiful and readily available from fancier groups all across Europe. Their ability to reproduce was also an asset.

Large and unwieldy, wireless sets also presented portability issues, a major obstacle for armies on the move. Two or three men were required to move a single set. Horses and mules likewise had a difficult time transporting the machines, and tanks and airplanes didn’t have enough room for a set weighing over 100 pounds. Pigeons were small and weighed just a few pounds, however. A single soldier could carry several in a knapsack or box on his back. Dozens more could be moved all at once with a mobile loft. Tanks and airplanes could easily accommodate a crate of pigeons.

Wireless stations brought unwanted attention to trenches as well. To receive and transmit messages, a basic trench wireless station required a thirty-feet high mast with aerials. For enemy aircraft flying over trenches in search of targets, this was a godsend. Pigeon lofts were much more conspicuous; they could be concealed in out-of-the-way corners and easily camouflaged.

Finally, there were issues with the medium itself. Wireless transmissions often were unreliable and range was impacted by atmospheric conditions. They could be jammed or intercepted by the enemy, too. Users also had to know how to use Morse Code to send or receive messages. Pigeons had a success rate of 97% when flown during optimal conditions. Electronic devices could not be used to interfere with the birds or track their flights—“A pigeon silently flies through the air, there is no wave that indicates its use, nothing that indicates its point of departure or destination,” Lieutenant Colonel A.H. Osman, the head of the British Pigeon Service, reflected in his post-War memoir. No foreknowledge of a special cipher was required to handle pigeons, though it was well advised to use one in case a bird fell into enemy hands.

As the War drew to a close, radio finally overcame many of these early challenges, becoming an integral part of military operations. Yet pigeons had shown that they still had merit in the electronic age. Militaries, therefore, opted to keep their pigeon services after the War’s conclusion, retaining them through the Interwar Period and World War II. By the end of the ‘50s, radio communications had advanced to the point where pigeons seemed truly obsolete. Many militaries shuttered their pigeon services at this point. Radio had finally won the day.

Or so it would appear. Even in the twenty-first century—where radio waves sustain internet connections and communications satellites—pigeons can still rise to the occasion, should the opportunity arise. In rural areas, radio and internet are often unreliable at best and non-existent at worst. Natural disasters can also interrupt these services. For these reasons, the Odisha Police regularly used pigeons to carry dispatches between stations in East India into the 2000s. Military applications also continue to exist. Future conflicts will inevitably involve electronic warfare tactics, not unlike those encountered in the First World War. Keen to these threats, the French and Chinese armies each maintain a reserve of pigeons to be deployed in the event of war.

Perhaps pigeons and radio can coexist peacefully. One might even say they have a complementary relationship—Pigeons fill in the gaps when radio signals break down or can’t reach their intended destination. But, what if this relationship isn’t entirely benign? Is it possible that radio waves actually harm pigeons?

For over a century, fanciers living near radio stations have seen a diminishment in their homers’ navigational skills. In 1910, a prominent British fancier reported that his flock had been experiencing increasing losses ever since the advent of wireless telegraphy. He argued that it interfered with their homing instinct and even speculated that the waves themselves were killing his birds. An article from 1913 noted that whenever a pigeon race occurred near a wireless station, an unusual number of birds failed to find their way home. A raft of similar reports surfaced throughout the ‘20s and ‘30s, as radio stations popped up all over the country. These observations described a disturbing trend. As homing pigeons flew over a radio transmitter, they became disoriented, not knowing in which direction to fly. Once the birds passed over the antenna, the confusion dissipated. Shortwave radio signals—transmissions on frequencies between 3 to 30 MHz—intensified the symptoms, while broadcasts below 100 watts lessened them.

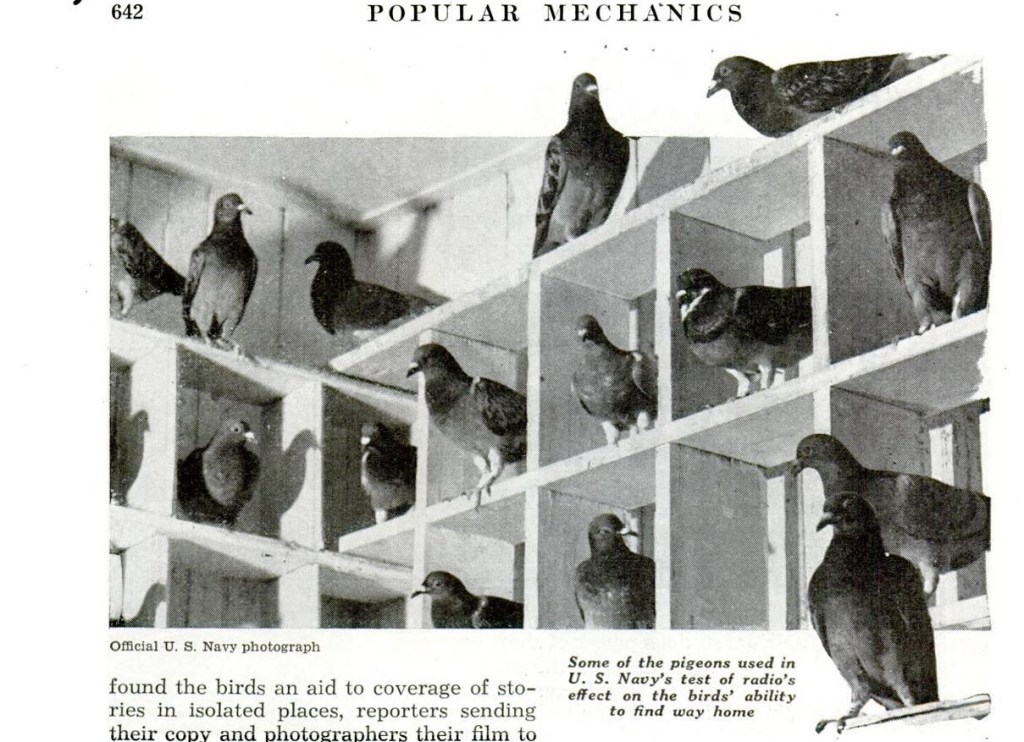

In 1937, the US Navy weighed in on the phenomena. Lieutenant George F. Watson, the officer in charge of the Navy’s loft at Lakehurst, New Jersey, investigated the effects of shortwave on the Navy’s birds. He released one set of birds near a shortwave radio station while it was transmitting, and another set fifteen minutes later after the station had stopped operating. Birds in the former group fluttered around the station in confusion for nearly twenty minutes, then made the ten-mile trip in forty-nine minutes, while the latter group made it in nineteen minutes. Two more trials achieved similar results. This gave naval officials heartburn, as it hinted at “the possibility that usefulness of the birds may be curtailed sharply.”

What was it about radio waves that caused them to harm pigeons? An early explanation invoked the concept of luminiferous ether, a hypothetical medium for the propagation of light. It was speculated that pigeons had a “sixth, or electric sense,” that was “in touch with the ether, that mysterious fluid which scientists declare to pervade everything in the universe on earth and in the air.” Per the thinking at the time, whenever radio waves traveled through the ether and interfered with “the ordinary waves of the ether,” such as light, it affected the birds’ sense of direction. After the ether theory had been consigned to the dustbin of history, later studies focused on magnetoreception. Pigeons, like all other migratory birds, have a magnetic compass hardwired into their brains that taps into the earth’s magnetic field, helping them find their way home. A study published in 2014 concluded that exposure to frequencies of up to 5 MHz—a chunk of the spectrum that encompasses AM radio and some shortwave bands—could interfere with this internal compass. The amount of exposure necessary to trigger this was “equivalent to what a bird in flight might experience five kilometers away from a 50-kilowatt AM radio station.” One scientist has called for society to gradually abandon its use of the AM bands.

As we said at the beginning of this blog, pigeons and radio have a complicated relationship. It ranges from adversarial to complementary to harmful. In spite of all predictions to the contrary, though, radio has yet to best pigeons.

Sources:

- Barik, Satyasundar. “Delivered by Pigeon Post in Cuttack.” Return to Frontpage, The Hindu, 5 May 2018, https://www.thehindu.com/society/delivered-by-pigeon-post-in-cuttack/article23784652.ece.

- Blazich, Frank. “In the Era of Electronic Warfare, Bring Back Pigeons.” War on the Rocks, 26 Feb. 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/01/in-the-era-of-electronic-warfare-bring-back-pigeons/.

- Dubenskij, Charlotte. “World War One: How Radio Crackled into Life in Conflict.” BBC News, 18 June 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-27894944.

- “Golden Age of Radio in the US.” Radio on the Frontlines: WWI and WWII | DPLA, https://dp.la/exhibitions/radio-golden-age/radio-frontlines/?item=671.

- Hartley-Smith, Alan. Marconi Heritage, http://marconiheritage.org/ww1-land.html.

- LeRoc, Norman, “Ancient Air Messengers for Modern War,” American Squab Journal, Vol. 7, No. 6, June 1918, at 173.

- Kirschvink, Joseph, “Radio Waves Zap the Biomagnetic Compass,” Nature, Vol. 509, May 15, 2014, at 296-297.

- “Mare Island Naval Radio Station.” Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/technology/communications/radio/ug-21–us-naval-california-radio-station-collection/mare-island-naval-radio-station.html.

- Morelle, Rebecca. “Electrical Devices ‘Disrupt Bird Navigation’.” BBC News, 7 May 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-27313355.

- Osman, A.H., Pigeons in the Great War, at 17 (1928).

- “Pigeons Delayed by Radio Waves,” Popular Mechanics, Vol. 68, No. 5, November 1937, at 642.

- “Radio Affects Pigeon Flight,” The Santa Fe New Mexican, Oct. 10, 1924, at 4.

- “Radio Waves Said to Affect Pigeons of Homing Variety,” Belleville Daily Advocate, Aug. 17, 1937, at 2.

- “Wireless Waves Kill Birds,” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Sept. 4, 1910, at 7.

- “Wireless Telegraphy.” New Articles RSS, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/wireless_telegraphy.

- “Wireless Worries Birds,” The Birmingham News, Dec. 7, 1913, at 41.

Home