-

Columba militaris helvetica: The Swiss Army’s Carrier Pigeons

A lot of ink has been spilled about military pigeons and their heroic actions during wartime. But what about those in peacetime armies? This blog is the first part in an occasional series examining military pigeon services in countries with strong traditions of neutrality.

With a tradition of neutrality dating back to the 1500s, it may come as a shock to some that Switzerland has a proud military heritage. The Swiss Armed Forces boasts over 100,000 servicemembers, most of whom are conscripts. It has an Army and an Air Force. A flotilla of military boats patrols the nation’s many lakes. A fascinating aspect of the country’s military history is its long-time use of homing pigeons. Many countries discarded their pigeon services after World War II—the Swiss Army maintained theirs until the 1990s. Although their pigeons never saw conflict, they provided invaluable services for over 77 years.

The Swiss military first began experimenting with pigeons in 1879. The results were not encouraging—the birds refused to fly over high mountains, elements that cannot be avoided in Switzerland. Over the next few years, trainers developed better birds and training programs, which led to improved results. The Federal Council took notice of these developments and, in 1889, ordered the creation of a nationwide pigeon service. The aim of the service was to ensure communication amongst the country’s forts in the event of an invasion by the German or Austro-Hungarian Empires. Stations were set up at forts in Basel, Zurich, and Weesen, a small village abutting Lake Wallenstadt. These were served by a central station in Thun. Each station had 120 birds, but in the case of a large war, the Swiss military planned to requisition pigeons from local fancier associations. During these early years, officials worried that marauding hawks would prey upon pigeons while they were carrying important messages. The government officially branded birds of prey an enemy of the state. Cantons offered bounties of up to four Swiss francs per bird.

While the Great Powers clashed during WWI, Switzerland rapidly expanded the presence of pigeons in its military. Reports circulated that the German military had developed listening stations that could intercept telephone conversations from up to ten kilometers away. Fearing interception of its military’s confidential messages, on August 27 1917, the Federal Council directed the military to set up a pigeon service. A fully separate unit was created to supply pigeons for the Army, the Swiss Army Carrier Pigeon Service. Officers and soldiers, as well as members of the auxiliary and volunteer forces, cared for the pigeons and provided technical advice. This arrangement lasted until 1951, when the Service was reorganized and placed under a telecommunications unit, where it would remain until its decommissioning. From 1940 onward, women served in the unit, a feature absent from other military pigeon posts.

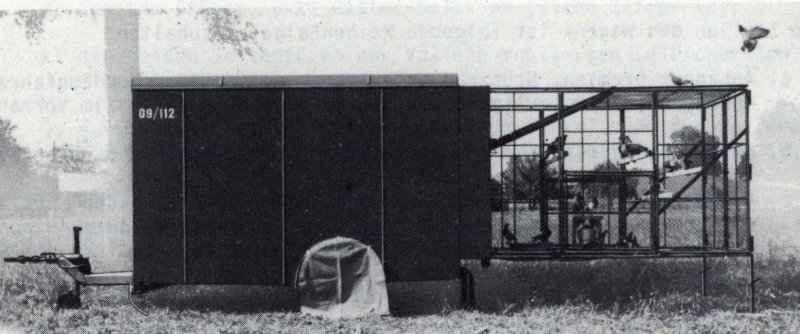

Throughout its existence, the Swiss Carrier Pigeons Service would maintain nearly 3,000 birds in twenty-three lofts scattered across the Alps and Jura regions. Eight mobile lofts were also available for flexible operations. Initially little more than horse-drawn carts, in 1959, a four-wheeled trailer that could house sixty-four birds was adopted by the Service. Aside from the pigeons it owned, the Army had access to nearly 30,000 birds, thanks to the patriotism of private fanciers. Indeed, since 1902, fanciers groups had entered into contracts with the government to turn over their pigeons in case of war or peacetime disasters. In exchange, the Army provided private breeders with free pigeon food and reimbursements for small expenses.

Working together, the Army and private fanciers devised breeding and training programs to develop pigeons acclimated to the country’s diverse landscape. A loft in the Sand-Schönbühl area served as the breeding depot for the Army’s birds. To safeguard breed standards, the military exercised tight control over the types of birds fanciers could raise—no pigeons could be imported into the country, absent express permission from the military. The Army’s training exercises involved regularly flying the birds over river valleys, forests, and mountains. Private fanciers had to ensure that their birds were fit for duty, too. Each year, their pigeons were subjected to a two-week refresher course in which they were transported via train to a border city hundreds of kilometers away and released; as they flew back home, the birds traveled extensively over mountain ranges.

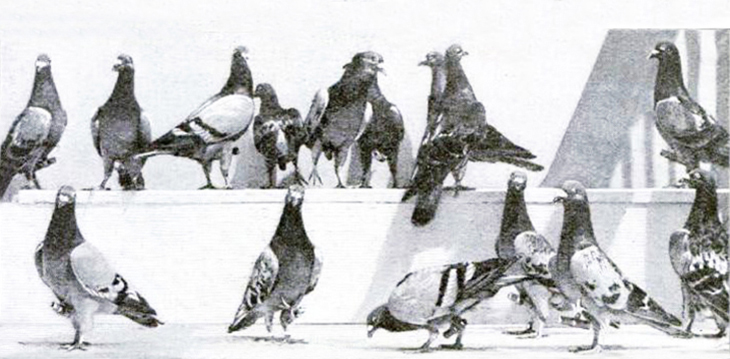

A top-tier bird emerged from these intense breeding and training efforts. Dubbed Columba militaris helvetica, this breed was robust and highly adaptable, ideal traits for flights over mountainous terrain. The achievements of these birds are absolutely staggering. They could travel over 800 kilometers at speeds of 60 to 120 kilometers per hour, with 98% of them returning to their lofts. More than a third of the pigeons at one particular loft learned to fly at night. Some birds successfully made two-way flights and even three-way flights! Bird-for-bird, the Swiss Army had perhaps the most elite pigeon force the world had ever seen.

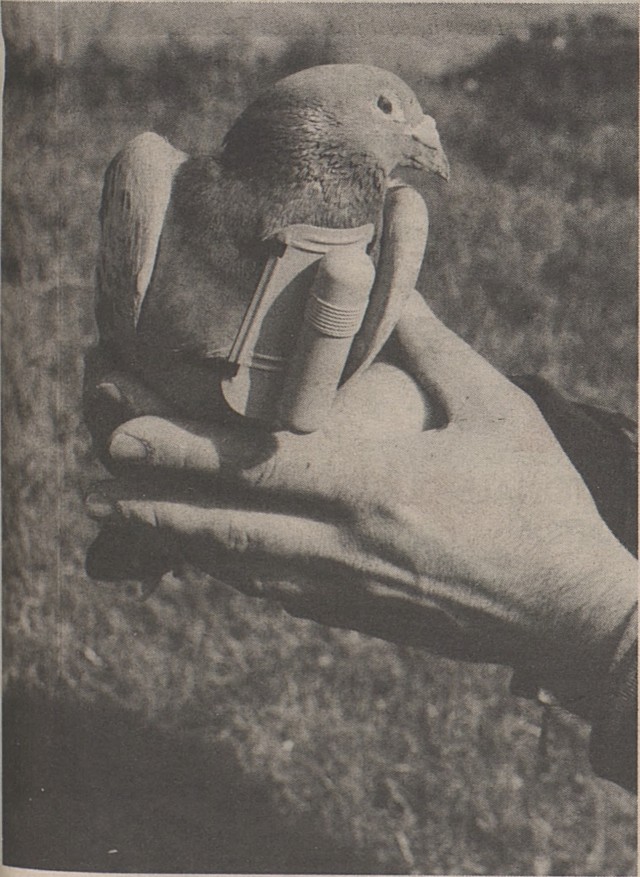

Given Switzerland’s firm commitment to neutrality, the Service’s pigeons largely served the needs of a peacetime Army. The birds guaranteed communication in times of catastrophe and from remote or difficult to access observation posts. They also served as couriers, delivering not only messages, but also sketches, photos, and microfilm to other stations. Because the birds could carry messages hundreds of miles away from their loft, their use as couriers freed up soldiers and vehicles for other work and saved on the cost of gas. But the threat of war could not be totally discounted. As the century progressed, threats of a German attack gave way to fears that the Soviet Union could invade from the northeast. To that end, soldiers, bicycle troops, and cavalry scouts frequently carried pigeons on their backs as they performed reconnaissance exercises.

At the start of the 1990s, Switzerland was the last European country to maintain a military pigeon service. But with the end of the Cold War, officials were eager to slash the Army’s budget. Many questioned why there was even a need for pigeons in a modern military. Servicemembers defended their pigeons, noting that the birds were cheap, not susceptible to electronic tracking or interference, and environmentally friendly—They were ”small, self-replicating biological missiles,” per Army regulations.

In spite of these advantages, the beancounters won out. On September 22, 1994, the Ministry of Defense officially decommissioned the Swiss Army Carrier Pigeon Service. Financial concerns were cited as the primary cause; the Service cost around 600,000 Swiss francs a year to operate. Officers and soldiers—including the head of the Service—received no advance notice whatsoever, hearing of the news once it had reached the media. The public was outraged to learn that the popular Service would be disbanded. To many, it brought back memories from the ‘70s, when officials dissolved the cavalry. Fanciers were especially incensed at this turn of events; after all, they had invested time and energy into training their birds for military service. They tried to collect enough signatures for a federal ballot initiative to preserve the Service, but nothing came of it.

The Service was granted a two-year transitional period to wind down its affairs. Dozens of the birds were auctioned off to breeders in Germany, France, and South Africa. Local fanciers, however, couldn’t bear the thought of losing such a unique breed. They pooled together their resources and set up a charitable foundation for the purpose of preserving Columba militaris helvetica for science and sport. The foundation entered into negotiations with the Army and eventually reached an agreement. Under the terms of the arrangement, the foundation would obtain the remainder of the pigeons and their equipment, and lease the Sand-Schönbühl pigeon station from the Army at a modest rent. On July 2, 1996, the Service officially ceased functioning.

The retired pigeons spent their final years at their old station. True to its mission statement, the foundation made the birds available for scientific study and sporting purposes. Scientists, aware of the pigeons’ unparalleled navigational abilities, recruited them for migration studies. Experiments were designed to track the birds’ flight paths, with the goal of clarifying how orientation cognition relates to the homing instinct. An annual summer racing contest—the Swiss Sand Derby—was launched by the foundation in its first year. Featuring the Army’s old birds as well as civilian pigeons, the races provided much needed funding for the lofts.

The foundation has also endeavored to preserve the breed. As of 2013, fifty descendants of the veteran flyers could be found in the Sand-Schönbühl station’s lofts. It is not an entirely risk-free life—hawks and martens occasionally target the birds. And, yet, this seems somewhat appropriate, considering the pigeons’ military heritage.

Swiss National Day is observed on August 1st each year. Only an official holiday since 1994—the same year the Swiss Army Carrier Pigeon Service was decommissioned—it is a day set aside to celebrate the founding of Switzerland. We here at Pigeons of War will be thinking of Columba militaris helvetica on that day.

Sources:

- A Tough Day for Pigeons. Tampa Bay Times, 23 Sept. 1994, https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1994/09/23/a-tough-day-for-pigeons/

- Auflösung Des Brieftaubendienstes Abgeschlossen, 2 July 1996, https://www.admin.ch/cp/d/1996Jul17.170649.6345@idz.bfi.admin.ch.html

- Bauer, Felix. Schweizer Armee Mustert Ihre Brieftauben Aus . Die Welt, 7 June 1996, https://www.welt.de/print-welt/article650105/Schweizer-Armee-mustert-ihre-Brieftauben-aus.html?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc.

- Bundesamt für Uebermittlungstruppen, Die Brieftaube alsUebermittlungsmittel unserer Armee, https://hamfu.ch/_upload/Brieftauben-Weisung-BAUEM.pdf?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

- Cadetg, Leonhard, Der Brieftaubendienst, Pionier : Zeitschrift für die Übermittlungstruppen, (1988).

- Die Brieftaube im Dienste unserer Armee, Schweizer Soldat : Monatszeitschrift für Armee und Kader mit FHD-Zeitung, (1928-1929).

- Genuth, Iddo. “Computer Controlled Pigeon.” TFOT, 16 Feb. 2007, https://thefutureofthings.com/5459-computer-controlled-pigeon/

- Interessengemeinschaft Übermittlung (IG Uem): Brieftaubendienst der Schweizer Armee

- Kroon, Robert L. “Swiss Budget Cutters Clip Army’s Platoon of Carrier Pigeons.” New York Times, December 23, 1994.

- Leybold-Johnson, Isobel. High-Tech Pigeons Reveal Navigation Secrets. Swissinfo.ch, 25 Sept. 2017, https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/high-tech-pigeons-reveal-navigation-secrets/74794

- Lipp, Hans-Peter, Brieftauben in der Armee – ein Anachronismus? Krieg im Äther. Vorlesungen an der Eidgenössischen Technischen Hochschule in Zürich im Wintersemester (1979/1980).

- Nicolussi, Ronny. Die Nachkommen Der Letzten Armee-Brieftauben . Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 2 Mar. 2013, https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/die-nachkommen-der-letzten-armee-brieftauben-ld.1021393

- “Protection of Military Carrier Pigeons,” The Auk, Vol. 35, 1918, at 253.

- Schmidlin, Rita, Brieftaubendienst: Gestern – heute – morgen, MFD-Zeitung, October 1992, at 50-52.

- “Swiss Army Pigeons Sold to South Africa, UPI, July 25, 1995.

- Tribelhorn, Marc. Schweizer Armee: Brieftauben Vor 25 Jahren Ausgemustert. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/schweizer-armee-brieftauben-vor-25-jahren-ausgemustert-ld.1510477?reduced=true

-

Bird-Dogging: Pigeons & Dogs Working Together in War

To get a message delivered under wartime conditions is no easy feat. As readers of this blog are well aware, this responsibility is often borne entirely on the wings of homing pigeons. But dogs have been used as messengers in combat, too. While soldiers are quite capable of running messages between units, a human runner is often too valuable a resource to spare. Dogs are plentiful, given their fecundity—thus, they are more disposable. They also possess myriad advantages over humans. A dog is much quicker than even the most agile soldier, running as fast as five kilometers in under fifteen minutes. Dogs have a keener sense of hearing and smell than humans and can see better in the dark. One instruction guide for combat dog handlers rhapsodized over their beneficial traits:

He is surer and faster; he can find his way in daylight and darkness, in any kind of weather, over rough or smooth terrain, open or jungle country, at high altitude, and in snow or cold. He can carry a message up to 1 mile at great speed. He is a difficult target, due to size, speed, and natural ability to take advantage of cover.

Dogs aren’t without their limitations. Although good sprinters, dogs don’t fare well at long-distance treks. In the 1890s, the French military compared the speed of bicycles, horses, carrier pigeons, and dogs while on maneuvers. The pigeons arrived first and the dogs were dead last. Excessive familiarity with the animal renders it useless. As dogs are always popular with troops, this requires handlers to exercise constant vigilance.

During the latter-half of the nineteenth century, armies began incorporating dogs into their operations, with Germany leading the pack. Through trial and error, military dog schools developed a set of criteria for selecting the perfect messenger dogs. The ideal candidate needed to possess a high degree of intelligence and energy, stamina and loyalty. Unlike sentry, attack, or scout dogs, aggression was not necessary, though the dog would need to defend itself if captured. Because the dog needed to have a strong bond with only its handlers, it should be aloof toward strangers. As far as size, the dog should be small enough to avoid being a target, yet large enough to traverse difficult terrain. Although a variety of breeds met these standards, Airedale Terriers were valued the most by handlers, followed by German Shepherds.

In training them for message duty, military authorities typically divided the dogs into two sub-categories. Messenger dogs delivered a message from one point to another. They were simpler to train and required only one handler. Liaison dogs could travel back-and-forth between two handlers. As this task was more complex, it took longer to train the dogs. After training, the dogs were ready for combat service. Soldiers heading to the frontline would take a dog from its handler, who remained behind. When it was time to send a message, the soldiers placed a note in a pocket or tube on the dog’s collar and set it free. The dog then would run back to the last place it had been with its handler. If the dog had been trained for liaison service, it could be sent back to the frontline with a reply message for its second handler.

Why did militaries need to rely on dogs to carry messages when homing pigeons were available? After all, nearly every European military had a pigeon service at this point. When it came to long-distance transmission, the pigeon was superior to the dog in every way. However, if a dispatch needed to be transmitted over a short-distance—say a couple of miles—the inverse was true. Unlike pigeons, dogs could travel at night or in inclement weather. Dogs also weren’t rooted to a particular location; they could return to wherever they had last been with their keepers. Pigeons, in contrast, will only fly towards their home loft. This led to the most significant advantage: dogs could be trained to travel to and from a location, thus allowing for two-way communication between handlers.

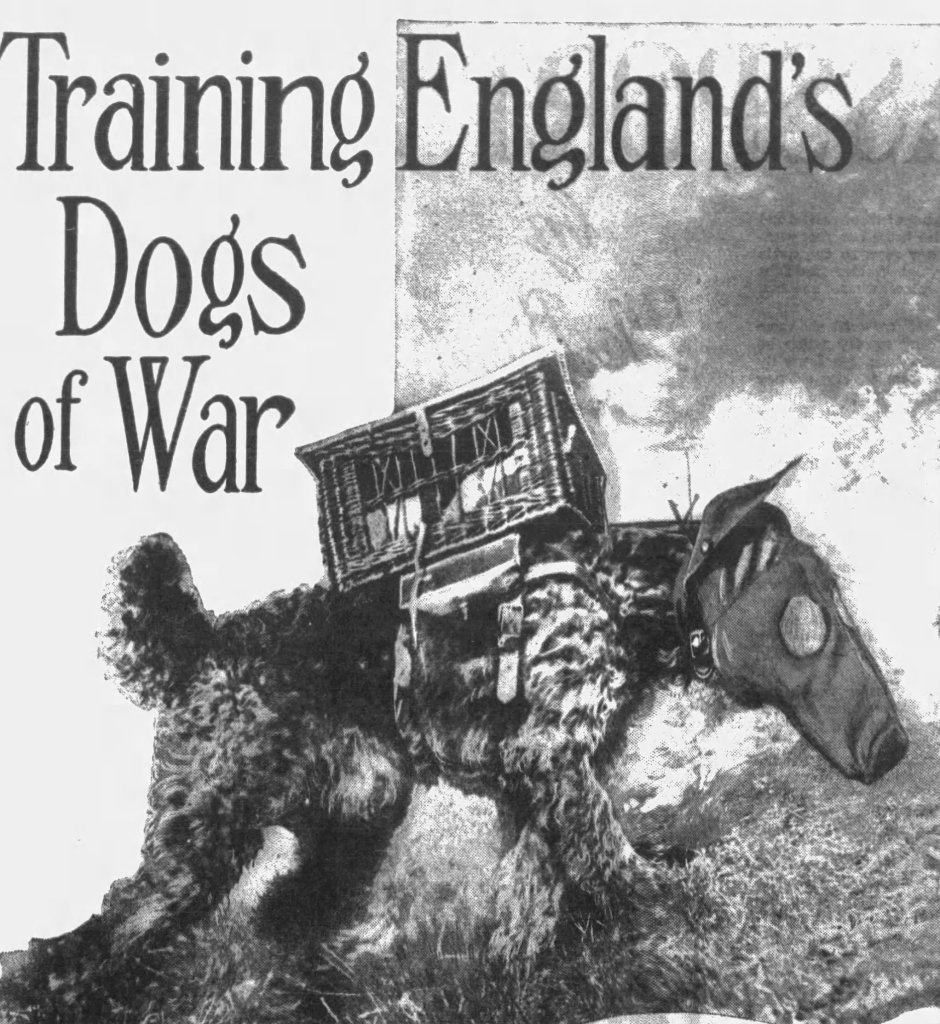

Not every military had the resources for training liaison dogs, however. The British War Dog Service never trained its dogs for liaison work during the First World War—they simply could not spare the extra manpower. Even with liaison dogs, there was always the risk that the dog might get hurt and not return right away (or at all). Handlers, therefore, realized that if they trained their dogs to carry pigeons, the birds would complement the dogs’ messaging abilities. With pigeons, messenger dogs could maintain two-way communication between the frontline and HQ and liaison dogs had a better chance of getting a reply delivered. At a more utilitarian level, a dog trained to transport pigeons freed up soldiers and vehicles for other work.

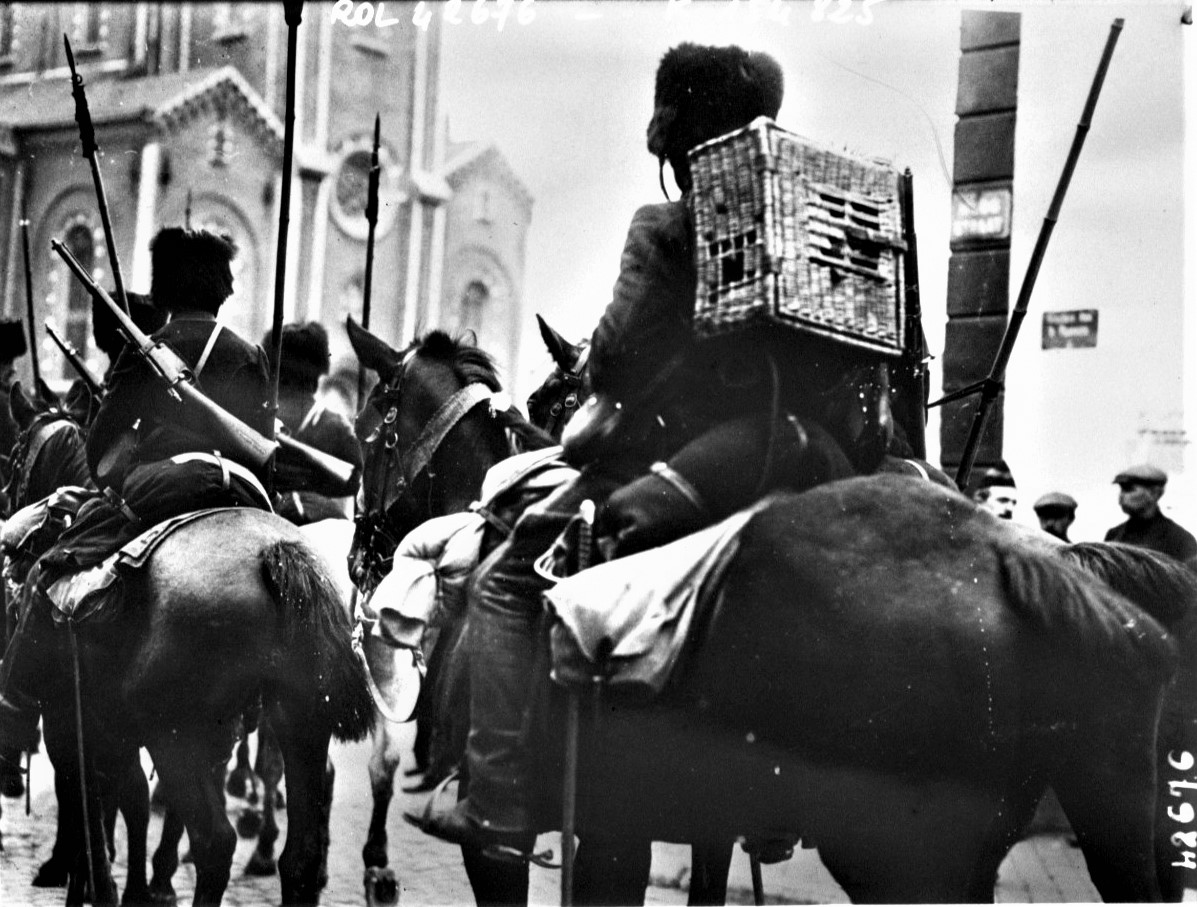

Throughout both World Wars, most of the armies employed messenger dogs. As the frontlines were often only a few miles from HQ, handlers paired their dogs with pigeons. These dogs faithfully carried their birds across trenches, under barbed wire, and through brush amidst constant gunfire, artillery barrages, and gas attacks. The methods by which the dogs transported the pigeons evolved over the years. Initially, dogs carried pigeons in wicker baskets strapped to their backs. A basket held three to six birds, which were fastened to the basket’s sides to provide resistance while the dog ran. Eventually, a harness was developed for securing pigeons around a dog’s mid-section. Some versions of the harness used side pouches, while others incorporated smaller wicker baskets. The US Army Signal Corps abandoned the use of harness baskets in 1944, after discovering that the birds bounced off the sides and damaged their feathers during the dogs’ training exercises. Handlers fashioned a softer medium out of the cardboard canisters of spent artillery shells.

The most celebrated account of a dog and pigeon working together occurred during the Verdun Offensive of 1916. Soldiers at a garrison had been ordered to defend a village at all costs, since it was located in a strategic spot. As the Germans advanced into the area, the garrison started to run out of ammunition. To make matters worse, the Germans organized a battery on a hill overlooking the village. Without reinforcements, the battery soon would wipe out the village and garrison. But communication with HQ was impossible; the garrison’s telegraph and telephone lines had been cut and their last homing pigeon had been shot out of the sky. The situation looked dire. Suddenly, a black dog wearing a gas mask and sporting “wings” on his shoulders came bounding across the village. A handler recognized the dog as one of his own: Satan, a greyhound-collie mix. In spite of his speed, the Germans managed to shoot Satan. The dog carried on, though, limping on three legs toward the soldiers. When they inspected the dog, they found a note from HQ promising that assistance would be sent within a day. They also noticed that Satan’s “wings” were actually pigeon baskets. The commandant rapidly scribbled out messages detailing the location of the German battery. The birds were released with the messages. The Germans shot down one before it had made it a quarter of a mile, but the other flew back to its loft. Within an hour, the garrison’s soldiers knew the village would be spared as they heard the thunder of French guns raining down upon the battery. Satan and the nameless pigeon had saved countless lives that day.

The title of this blog is Bird-Dogging, which means doggedly seeking out someone or something. As message bearers, that is the mission of dogs and pigeons in combat. The dog seeks out its handler, the bird its loft, while facing great peril. We are fortunate that these animals possess such single-minded devotion to the task at hand.

Sources:

- An Experiment with Teaming Pigeons and Dogs, United States Army Communications-Electronics Command, https://cecom.army.mil/PDF/Historian/Feature%202/Blog%20Teaming%20Pigeons%20and%20Dogs.pdf

- Baynes, Ernest Harold, Animal Heroes of the Great War, at 171, 179-182 (1925).

- ———. “Mankind’s Best Friend,” The Book of Dogs, at 17 (1919).

- Bird-dog.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bird-dog

- Brouwer, Sigmund, Innocent Heroes: Stories of Animals in the First World War, 79-80 (2017).

- “Dogs as Soldiers,” The Review of Reviews, Vol. 14, Jul. – Dec. 1896, at 530.

- “Dove of Peace Is Real Eagle of War,” San Francisco Chronicle, Oct. 31, 1920, at 5.

- “Heroic Dash of Dog, After Being Shot, Saves Lives of French Troop,” The Birmingham News, May 23, 1926, at 77.

- Kane, Gillian. “Meet Sergeant Stubby, America’s Original Dog of War.” Slate Magazine, Slate, 8 May 2014, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2014/05/dogs-of-war-sergeant-stubby-the-u-s-armys-original-and-still-most-highly-decorated-canine-soldier.html

- “Pigeons Carried By Dogs to Help in Training,” Popular Mechanics, Vol. 50, No. 5, Nov. 1928, at 800.

- Richardson, E.H., British War Dogs, at 75-75 (1930).

- War Department, “War Dogs,” Technical Manual No. 10-396, Jul 1, 1943, at 121.

-

The Russian Empire’s Pigeon Stations: 1871 – 1916 A.D.

On January 27th, 1871, three homing pigeons floated out of Paris on the manned balloon Le Richard Wallace. These birds had been tasked with the solemn duty of carrying messages from central France into the besieged city. Yet this would be the final mission of the Paris pigeon post; city officials would sign an armistice with the Prussians the very next day. Although it had lasted for only four months, the pigeon service had inspired the world, showing that communication could be maintained in wartime. In the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, the Great Powers of Europe scrambled to stock their militaries with pigeons. Which country would be the first to win this arms race over carrier pigeons?

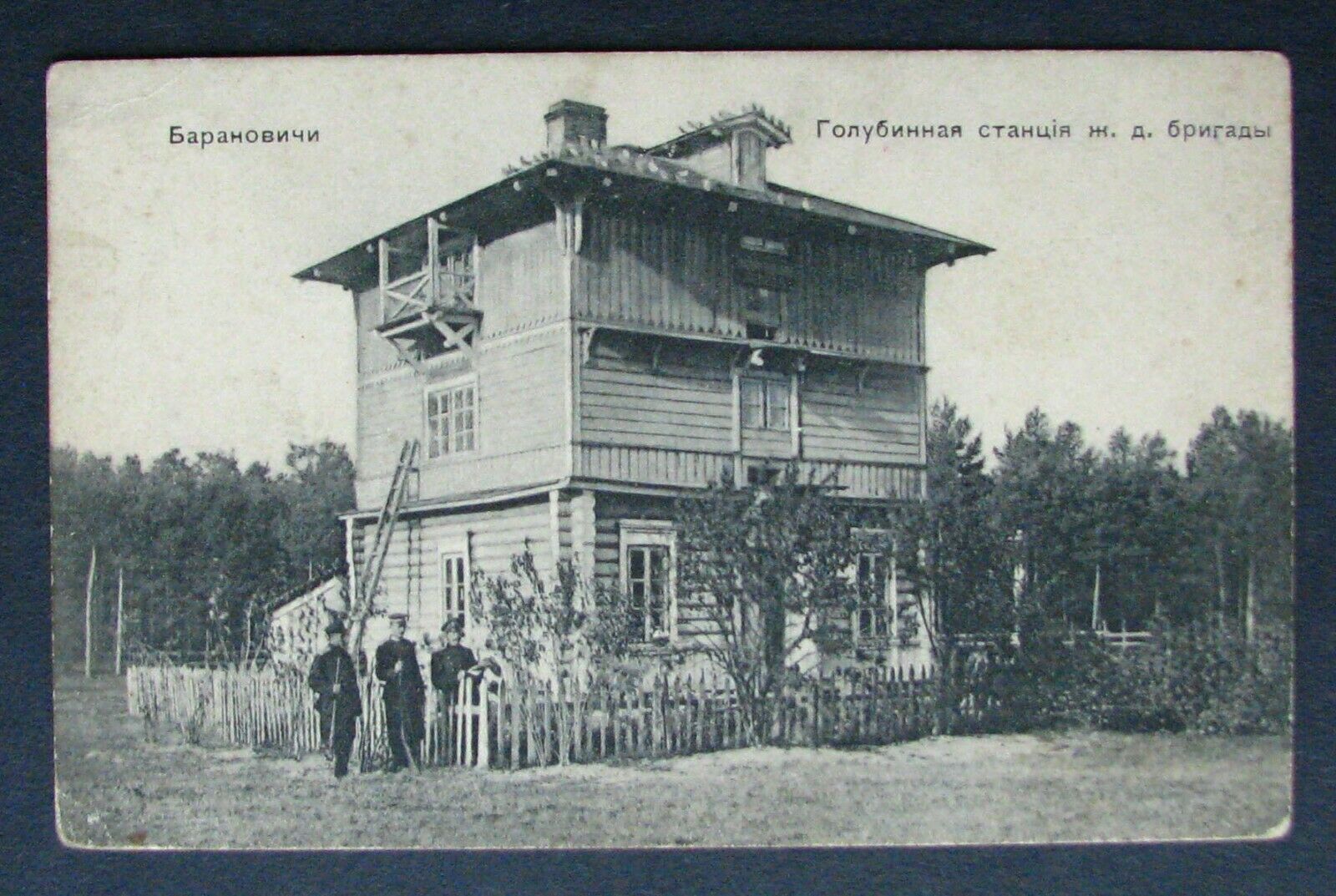

Surprisingly, the Russian Empire—a country viewed by many as being hopelessly stuck in the Middle Ages—beat all of them to the chase. In April 1871, just two months after the Paris pigeon post had ceased functioning, Russian officials approached Victor La Perre de Roo—the French fancier who had convinced the Parisian government to use pigeons—about setting up a military pigeon system in Russian Poland. Roo turned them down, but he did advise the Czar’s ministers on the basics of setting up a pigeon service for the Army. A service soon was established between St. Petersburg, the imperial capital, and Krasnoye Selo, a town that hosted annual military maneuvers. Lofts quickly popped up all across the Empire, with stations in the capitals of modern-day Poland and Ukraine.

These early lofts faced setbacks. In spite of great expense, the pigeons’ performances failed to live up to expectations, leading to the shuttering of some lofts in 1883. Military authorities blamed the pigeons and the Russian landscape. The native stock of birds evidently was ill-suited for long flights, while the imported pigeons could not tolerate the Arctic climate, dying in large numbers. Meanwhile, the countryside was so “uniform and monotonous, that the birds had no landmarks to guide them, and consequently were very often lost.” It was also asserted that the service had been poorly organized and run by amateurs.

To remedy these issues, the service was placed under the aegis of the Army’s Engineering department. Gradually, a cold-hardy bird capable of long-distance flights was developed by selectively breeding for these traits in foreign pigeons. Through trial and error, four strains emerged as the clear winners: the English carrier pigeon and the Brussels, Antwerp, and Liege varieties. Funding for the stations also increased significantly, as thousands of rubles were allocated annually for their maintenance.

Following these improvements, the pigeon stations of the Empire’s western territories flourished. At first, the service was confined to Polish and Belorussian fortresses. A lieutenant-colonel, supported by a staff of officers, trainers, and servants, oversaw operations. Forts at Warsaw, Novogeorgiesvsk (Modlin), Ivangorod (Deblin), Luninets, and Brest-Litovski (Brest) kept lofts, allowing for communication amongst them. The amount of pigeons at each loft depended upon how many forts were within the birds’ flight paths. The Brest-Litovski loft, for instance, needed pigeons trained to fly in four different directions, as it was situated centrally amongst the five forts. The loft accordingly harbored the most birds, serving also as a breeding depot. By 1891, the lofts housed 3000 birds.

The success of these pigeon stations prompted the Czar to issue ukases calling for more lofts. Additional lofts were built in Poland, while forts in present-day Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine adopted their own pigeon services. With this expansion, the military began exploring other ways in which the pigeons could be utilized. The Libau (Liepaja), Sevastopol, and Odessa stations, which were headquartered at naval bases, trained their birds for maritime service. These birds relayed messages from outgoing warships to the forts. Officials also experimented with outfitting cavalry troops with pigeons, which would allow them to send dispatches back to HQ while out in the field. Preliminary trials showed that the birds could deliver messages in one-fifth of the time it took a mounted orderly to do so. Such a service would be especially ideal for scouts exploring terrain unsuited for telegraph service. In Russian Turkestan, an enterprising lieutenant stationed in Tashkent trained pigeons for this express purpose. When his brigade set up camp twenty-one miles away while on maneuvers, their pigeons delivered 228 messages to the base over four months.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the Russian military felt confident to deploy its pigeons in a massive war game planned for September 1902. Designed to be “on a scale of magnificence unequaled in the history of European manoeuvers,” the games would simulate attacks on Moscow and Kursk, pitting two armies of 150,000 soldiers against one another. Each army was directed to equip their cavalry with pigeons and transmit any gathered intelligence to the higher-ups via telegraph. By all accounts, the pigeons’ performances were “satisfactory and useful.”The pigeons had fared well under simulated wartime conditions. But how would they measure up in an actual conflict? An answer would soon be forthcoming in the Russian Far East.

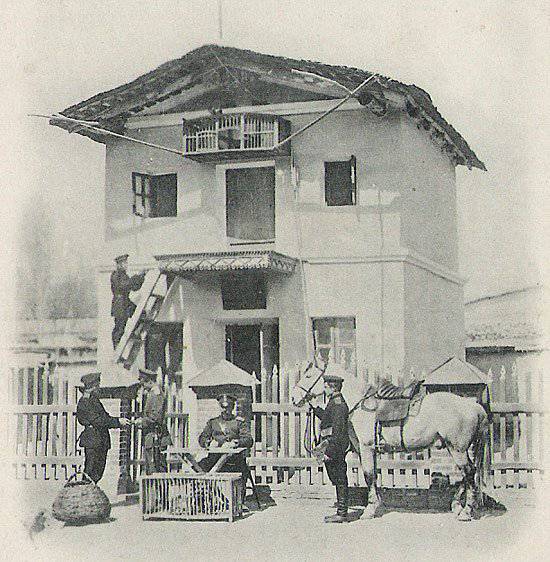

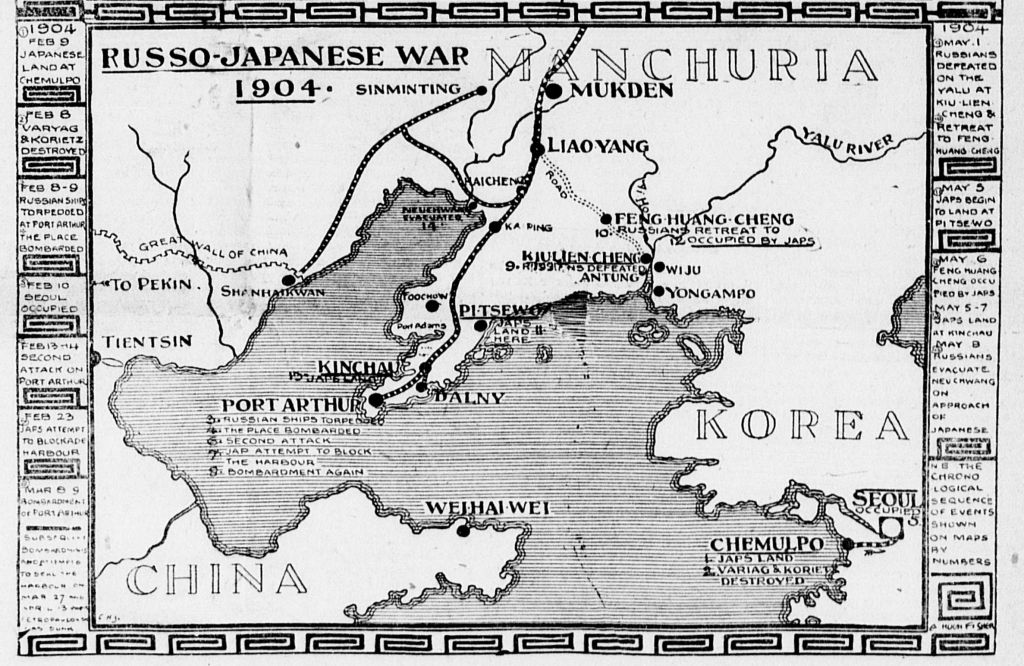

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, the Empire had gained a foothold in Northeastern China, establishing outposts throughout Manchuria. In 1898, Russia obtained a lease of Port Arthur, a natural harbor on the southern tip of the Liaodong Peninsula, from China, intending to use the site as its only warm-water port on the Pacific coast. In fortifying its Manchurian possessions, the Russians made sure that each one contained a military loft. Japan resented Russian encroachment into its sphere of influence. The two countries tried to mediate their issues for several years, but nothing came of it. On February 8, 1904, the Japanese Navy suddenly attacked the Russian fleet at Port Arthur without warning. War was declared shortly afterwards.

The Japanese Army launched an all-out assault against Port Arthur. Telegraph lines and railways were destroyed to isolate the Port. Fortunately, the Port had a fledgling pigeon post in place. Within days of the War’s start, a French colombophile society had approached Port Arthur about setting up a pigeon service for communicating with other districts in Russian-controlled Manchuria. Officials immediately accepted the offer. Pigeons from strategic Manchurian cities were collected and sent to Port Arthur, while the Port’s birds were shipped out to those areas. Such a system, in theory, would allow for two-way communication to be sustained.

For the next several months, Port Arthur relied on its pigeon post for communicating with the outside world. In May, pigeons carried status reports to the Manchurian Army’s headquarters in Liaoyang and delivered positive news to Mukden (Shenyang) that two Japanese battleships had struck mines outside the Port’s harbor. In June, Chefoo (Yantai) and Newchang (Yingkou) received updates from the Port’s commander, General Anatoly Stessel. These seem to be the only substantive messages received from the Port. Attempts at contacting the Port were likewise fraught with difficulty. Russian authorities had arranged for Chinese junk boats to ferry Port Athur’s birds across the Yellow Sea to Chefoo for espionage work. Agents in the employ of Russia were instructed to gather information about the Japanese fleet and send it by pigeon. Only one of these pigeons made it back to Port Arthur. Meanwhile, at Liaoyang, the Manchurian Army had built a special station to house the Port’s pigeons, but only three of them ever returned. The failure of so many pigeons to home successfully may stem from the Japanese Army’s recruitment of hawks to intercept them.

In spite of the difficulties experienced during the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian Empire continued to maintain its pigeon stations, even building a “first-class station with 1000 pigeons” at the naval base in Vladivostok. On the eve of the Great War, Russia boasted ten military pigeon stations stretched across both ends of the Empire. When hostilities commenced in 1914, the Sevastopol station proved its worth when one of its birds alerted the fortress that the Turkish battlecruiser Yavuz had the city within its sights. A Russian destroyer had spotted the enemy vessel and tried warning the fort, but the ship’s radio failed. Thankfully, sailors found one of Sevastopol’s birds on board the ship and released it with news of the threat. Further information on how the pigeon service assisted Russians during the War is scarce, but they undoubtedly facilitated communication between forts and aided reconnaissance activities. The stations would not survive the War, however. As Russian forts along the Eastern Front fell, their pigeons were evacuated along with the troops. On March 23th (April 5th), 1916, the Czar’s government shut down the Empire’s three remaining pigeon stations. The birds were shipped to a newly formed military pigeon depot in an effort to preserve the stock while the War persisted.

After 45 years, the Russian Empire’s pigeon stations were no more. Yet memories of the birds’ unique capabilities persisted within military circles, even after the Soviet Union had risen from the Empire’s ashes. Soviet military brass began incorporating pigeons into aircraft exercises during the mid-’20s. In 1928, the Deputy People’s Commissar of the USSR for Military and Naval Affairs recommended that the armed forces adopt a pigeon service. At the start of the Great Patriotic War, the Red Army boasted over 250 pigeon stations with 30,000 pigeons. These stations would prove their merit in battles against the Germans. But that’s a story for another day.

Sources:

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 123-24, 130-31 (1888).

- “An Unintelligible Message,” Manchester Evening News, May 11, 1904, at 2.

- “Carrier Pigeons for Port Arthur,” The Evening Mail, Feb. 23, 1904 at 10.

- “Carrier Pigeons in Service,” Palladium-Item, June 6, 1904, at 3.

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 240 (1901).

- Department of Marine, “Report on Messenger Pigeons,” Twenty-Third Annual Report of the Department of Marine, for the Fiscal Year Ended 30th June, 1890, at 205.

- Egorov, Boris. “How Pigeons Helped the Red Army to Win in World War II.” Russia Beyond, 8 Dec. 2021, https://www.rbth.com/history/334499-how-pigeons-helped-red-army

- “From the Besieged,” Herald and Review, Jun. 5, 1904, at 1.

- “Meek Spies.” Военное Обозрение, 22 Oct. 2015, https://en.topwar.ru/84473-krotkie-shpiony.html

- “Military Pigeon Post at the Kursk Maneuvers,” Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. 32, 1903, at 277.

- “Pigeons in the War: Japanese and Russian,” Black & White, Vol. 27, June 18, 1904, at 914.

- “Pigeon Post Sea Station in Karosta.” Military Heritage Tourism, Interreg Estonia-Latvia, https://militaryheritagetourism.info/en/military/sites/view/460?0

- “Port Arthur,” Manchester Evening News, May 11, 1904, at 2.

- “Port Arthur and Mukden,” Liverpool Daily Post, May 11, 1904 at 5.

- “Russia – Army Maneuvers,” Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Vol. 6, No. 2, Jul. – Dec. 1902, at 1366.

- “Russia is Rejoicing,” Albine Weekly Reflector, May 26, 1904, at 12.

- Schuyler, Walter, S., Reports of Military Observers to the Armies in Manchuria, Vol. 1, at 154 (1906).

- Sergeev, Evgeny, Russian Military Intelligence in the War with Japan, 1904-05, at 95-96 (2007).

- Toepfer, Capt. “Technics in the Russo-Japanese War,” Professional Memoirs, Corps of Engineers, United States Army, and Engineer Department at Large, Vol. 2, No.6, at 191 (1910).

- “Train Falcons for War Use,” Lancaster Teller, Mar. 2, 1905, at 6.

- “Will Play War in August,” Nashville Banner, Jun. 11, 1902, at 1.

- Историческая Справка По Станциям Военно-Голубиной Почты., http://www.antologifo.narod.ru/pages/list/histore/istPostG.htm

- ВОЙНА И ГОЛУБИ.ВОЕННО , Live Internet, https://www.liveinternet.ru/users/4768613/post351439272/#

-

Happy Presidents’ Day from President Wilson!

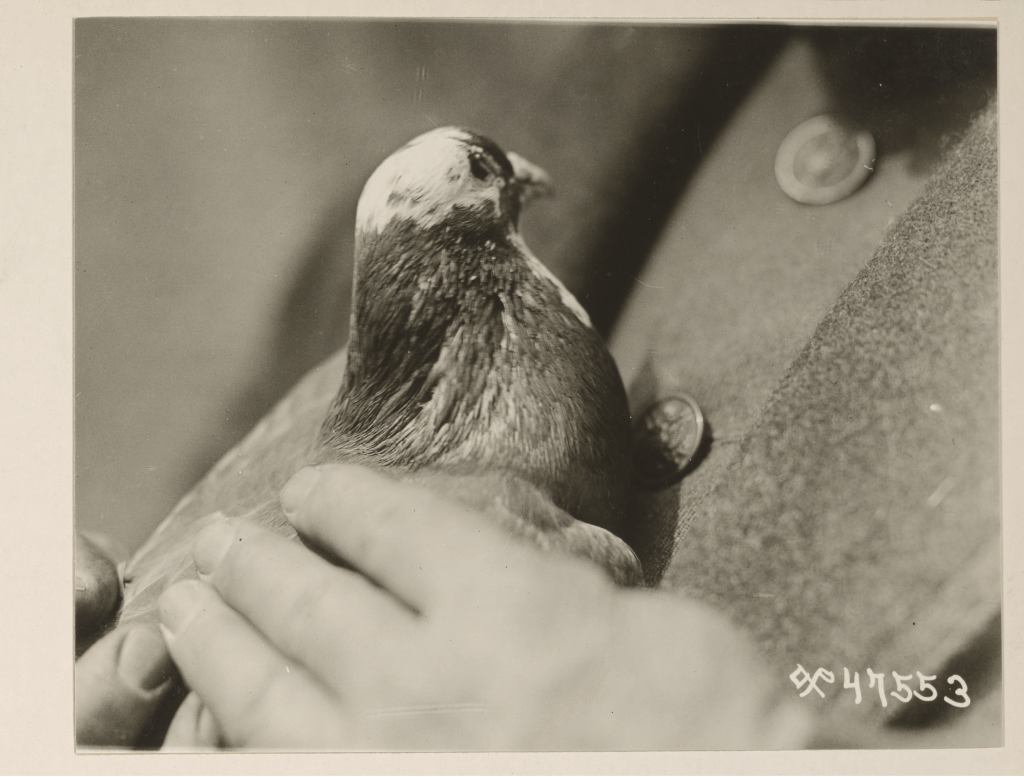

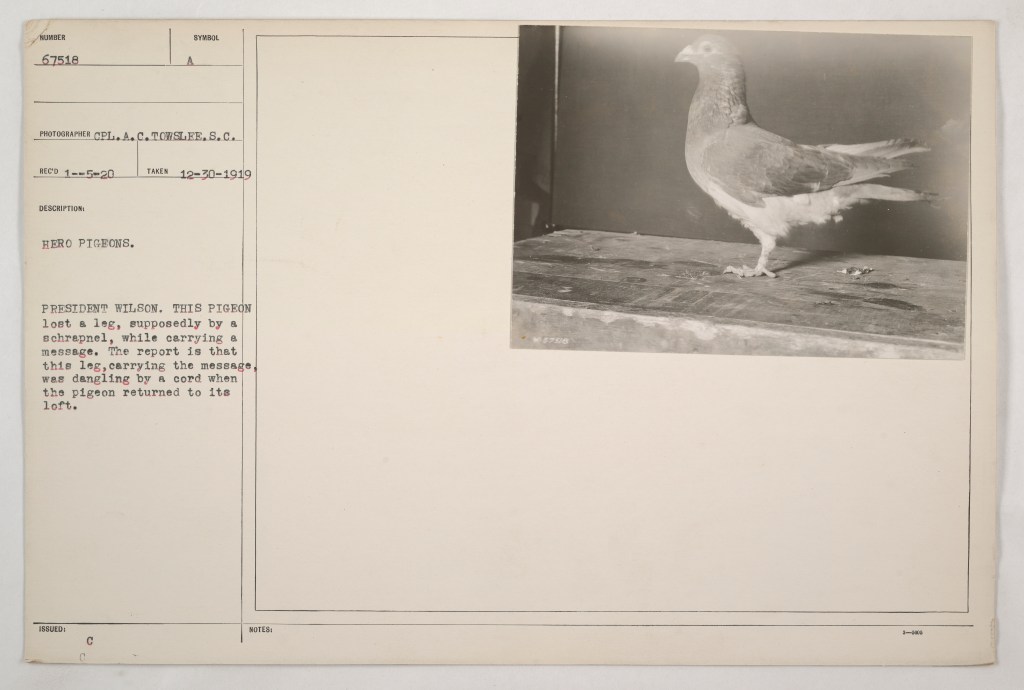

We here at Pigeons of War want to wish you all a very Happy Presidents’ Day! Presidents’ Day is an American holiday observed annually on the third Monday of February. It’s a day set aside to celebrate the achievements of America’s presidents. So it seems appropriate to write about President Wilson’s accomplishments today–the renowned homing pigeon of World War One, that is.

President Wilson was born in France around 1917 or 1918 in a loft under the care of the United States Army Signal Corps. In mid-September 1918, he received his first assignment: accompanying Lieutenant-Colonel George S. Patton’s Tank Battalions as they rode to the Saint-Mihiel salient. Patton had participated in simulated war games involving pigeons and was eager to deploy them in battle. The Tank Battalions carried a total of 202 birds into action, losing 24 of them in the process. President Wilson performed superbly during the Saint-Mihiel Offensive. He carried important messages from the tanks to his loft so rapidly, he received commendations from the Signal Officer of the First Corps.

As the fighting at Saint-Mihiel subsided, President Wilson was transferred to the Meuse-Argonne Offensive and placed with an infantry unit stationed near Grandpre. From September 26th to November 11th, 90 percent of the Signal Corps’ birds served in some of the bloodiest fighting in the War. On the morning of October 5th, President Wilson’s unit encountered enemy fire. He was released with a note requesting artillery support. On his way back to the loft, a piece of shrapnel sailed through the air and tore off his left leg. Nevertheless, President Wilson persisted and managed to return to his loft with the message, traveling over twenty kilometers in twenty-one minutes in spite of heavy fog and rain. What makes this flight all the more incredible was that it was only his second flight over the Meuse-Argonne Front.

While President Wilson was nursed back to health, his commanding officer, Lieutenant John L. Carney, wrote up an official citation memorializing his deeds, which was widely reprinted in American media. Doughboys in Europe and their families back home read about the bird’s courage under fire. His story–along with those of other Army pigeons–captivated the public.

After the War ended, President Wilson immigrated to the U.S. in 1919. He was an instant celebrity. He toured the country, appearing at conventions where he served as a tangible reminder of the sacrifices homing pigeons had made during the Great War. In January 1920, he and some of his Army buddies were the guests of honor at the annual Madison Square Garden Poultry and Pigeon Show. Accompanied by a cadre of body guards–the Chief of the Pigeon Officer of the Army and his staff–President Wilson quickly attracted the crowd’s attention. “All eyes strained to see President Wilson,” declared the American Pigeon Journal. It was noted that he was still in good physical condition, but the gravity of his injury was noticeable to all present:

He does not walk but hops in company with many others that came with him including a Homer with one eye shot out and Fritz, a German Staff bird wearing an Imperial Band, that was captured at St. Mihiel with a German message.

President Wilson eventually retired from the limelight and moved to the U.S. Army Signal Corps Breeding and Training Center at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey. It was a mostly quiet life, although he did take time to star in a film. After nearly a decade, his health began to fail. Reports of his decline were transmitted to the Signal Corps’ headquarters, “as if he were a wounded general,” one local newspaper observed. He died on June 8, 1929.

Officials decided to preserve his body and put it on display. When these plans were reported by the media, a ten-year old schoolgirl wrote to the Secretary of War, imploring him to inter President Wilson at the Arlington National Cemetery. The Secretary wrote back, claiming regulations prevented him from honoring the child’s wish. “I am sure, however, you will agree with me,” he wrote, “that by placing the pigeon in our military museum it will help to keep alive the memory of his historic and heroic deeds.”

Ultimately, President Wilson was stuffed and mounted and kept at Fort Monmouth for nearly a year. On March 22, 1930, his body was shipped to the Smithsonian Institution, escorted by a captain of the Signal Corps. There, he joined his fellow veteran Cher Ami, the hero of the Lost Battalion, and was featured as an exhibit for over seventy years. In 2008, the U.S. Army acquired President Wilson–he is currently on display at the Pentagon, just outside the Army Chief of Staff’s office.

If you find yourself in Washington, D.C. next Presidents’ Day, you should definitely take a trip to the Pentagon and see President Wilson in person. We can’t think of a better way of honoring the legacy of America’s presidents than by paying tribute to one of their most prominent namesakes.

Sources:

- Blazich, Frank A. “Feathers of Honor: U.S. Army Signal Corps Pigeon Service in World War I, 1917–1918.” Army History, No. 117 at 43-44.

- McLaughlin, Elizabeth. “Meet the Hero Carrier Pigeon That Saved US Troops During a WWI Battle 100 Years Ago.” ABC News, 5 Oct. 2018, available at https://abcnews.go.com/International/meet-hero-carrier-pigeon-saved-us-troops-wwi/story?id=58233076.

- “Mounted War Bird Sent to Museum,” The Daily Record, Mar. 22, 1930, at 3.

- “One of Our Bird Veterans of the War,” Popular Science, Vol. 97, No. 6, December 1920, at 68.

- “One of the Trio of Famous War Birds Saved Many Lives,” The Record, July 2, 1929, at 8.

- “Pigeon Heroes of World War Attract Attention of Hundreds at County Fair,” The Bulletin, Oct. 19, 1923, at 7.

- “Pigeons with Records in War Are on Exhibit,” The Indianapolis News, Jan. 5, 1920, at 6.

- President Wilson Attends Madison Square Garden Poultry and Pigeon Show,” American Squab Journal, January 1920, Vol. 9, No. 1, at 163.

- “War Bird Heroes on Visit to City,” The Starry Cross, June 1919, Vol. 28, No. 6, at 92.

- War Birds Filmed for Sound Picture,” The Daily Record, April 13, 1929, at 3.

- “Winged Hero Finds Friend,” The Ridgewood Herald, Jul. 2, 1929, at 1, 6.

-

The Belgian Pigeon Service During World War One

On August 4, 1914, German troops marched across the Belgium border toward the fortified city of Liege. Germany had declared war on Belgium a day before, after the country had refused to grant the German Army safe passage through its territory. The first battle of the Great War began in the early hours of August 6th as the Germans launched an assault against Liege. After nearly three months of intense fighting, Germany occupied most of the country and would hold it for the duration of the War.

Post-War accounts have focused largely on the lurid events that allegedly occurred during the invasion and subsequent occupation, known collectively as the “Rape of Belgium.” One story, however, has not been fully addressed: How did the Belgian Pigeon Service (BPS) fare against the German military?

Belgium is the birthplace of the homing pigeon. Nearly all of the world’s prize-winning homers can trace their pedigrees back to Belgian fanciers. Simply put, Belgians love their pigeons, and, to this day, pigeon racing is considered the national sport.

It’s no great surprise, then, that in the years leading up to 1914, the Belgium Army had created a pigeon service for emergency communications. Indeed, nearly every other Great Power in Europe had done the same after the Franco-Prussian War. That War had shown the world that pigeons could deliver messages reliably when telegraph lines had been cut.

Established in 1896, the BPS was managed by the Army’s engineer corps. A commandant oversaw operations, supported by a staff of non-commissioned officers and privates. The principal loft was housed in the top floor of a stone mansion in Antwerp, right outside the ring of forts encircling the city. Secondary lofts were later built in Namur and Liege, located to the south of Antwerp. Each loft housed hundreds of birds. By 1914, Antwerp’s loft supposedly had ballooned to 2500 birds.

Unlike the majority of pigeon services in Europe, the BPS didn’t provide soldiers or cavalry scouts with birds to use while out in the field. Rather, the service existed solely to ensure communication amongst Belgium’s fortified cities in case telegraphic services were interrupted. Trainers at the Antwerp, Namur, and Liege lofts taught the birds to fly back from each city, which allowed for two-way communication between the three cities. The birds’ flight paths eventually extended to Dendermonde to the east and Diest to the west, linking more forts with the BPS.

The BPS also operated a photographic studio in Antwerp to prepare messages for transmission. The studio utilized a microphotographic process, similar to the one employed by Paris’ pigeon post during the Franco-Prussian War. Messages were written out on a large blackboard, photographed and reduced in size, and printed on small strips of celluloid film. A single, two-inch strip contained several columns of text. A pigeon could easily fly with a dozen or more strips stuffed into its leg holder. The recipient had the choice of either reading the despatches under a microscope or projecting them onto a screen.

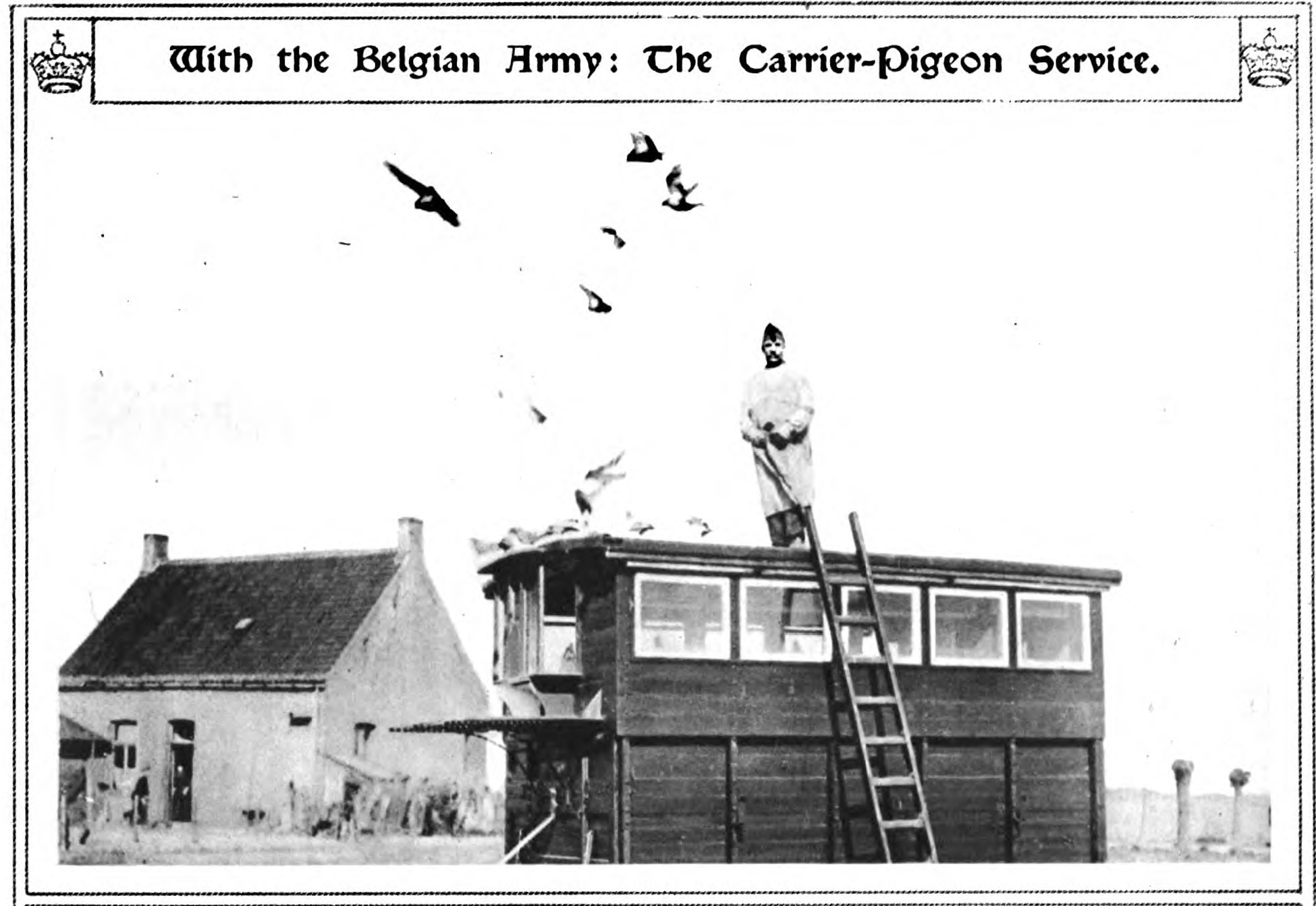

On the eve of World War One, Belgium was considered by some to have “the finest pigeon service in the world.” Led by Commandant G. Genuit, the BPS was ready, willing, and able to provide vital services in the event of conflict.

And, indeed, the pigeons served admirably in the opening weeks of the German invasion. A cipher was developed to conceal the meaning of messages, permitting encrypted reports to be passed between forts. The birds were also recruited for reconnaissance work. Scouts reconnoitering in occupied territory sent the birds back to the military lofts with tiny maps detailing German troop positions. This information helped the Belgian artillery inflict “heavy and unexpected casualties” on the Germans. German commanders were baffled—how had the Belgians discovered their positions so quickly? It took some time for them to realize pigeons were responsible for conveying this intelligence.

But Belgium’s fortresses could not withstand the might of the German artillery. Liege fell on August 16th. Namur surrendered nine days later. The government abandoned Brussels, while the Belgian Army retreated to Antwerp. The Germans occupied Brussels and ordered fanciers to destroy all of their carrier pigeons by September 15th or face a court martial. The Burgomaster of Brussels, however, convinced the German authorities to simply intern the birds in a public forum under German control. Hundreds of crates brimming with pigeons were deposited in one of the halls of the Parc du Cinquantenaire. Fanciers were permitted to feed their birds daily while German soldiers closely monitored their activities.

Antwerp was now in Germany’s cross-hairs. The siege of the city started on September 28th. Fierce fighting lasted for over a week. On October 8th, it was evident that German forces would take Antwerp by the end of the day. The Germans undoubtedly would confiscate the pigeons as spoils of war. Commandant Denuit had to act fast. He was forced to make a heart-wrenching decision. Writing eleven years later, Ernest Harold Baynes, an animal rights activist, described Denuit’s act of desperation:

[T]hat morning, with aching heart but with firm purpose, he took a torch and fired the great colombier, burning alive twenty five hundred of the finest pigeons in all the world, that they might not be forced into the service of the enemy. He was only just in time, for the Germans burst into the town at noon.

The city officially surrendered the following day.

Denuit’s great sacrifice prevented thousands of elite pigeons from falling into German hands. It was a tremendous blow to Denuit. Not only had he spent years of his professional life training the birds, he’d developed an intimate bond with them. Some accounts claim that he sobbed as he set the loft aflame.

During the occupation, the German military imposed strict conditions to prevent Belgians from using pigeons to aid resistance efforts. Pigeon fanciers and their lofts were kept under constant surveillance. Towns were fined thousands of francs whenever an inhabitant let loose a pigeon. Anyone caught using homers to send messages “regarding the movement of troops, troop trains or munitions” faced summary execution.

In spite of these actions, a new iteration of the BPS would soon reemerge in the only unoccupied piece of territory left in Belgium: a 19-mile strip of land near the North Sea coast. Rallied by King Albert, the remnants of the Belgian Army established a presence there and continued to fight against the occupying forces. By 1917, pigeons once again had been integrated into military operations. Mobile pigeon vans, similar to the ones used by the French, transported the birds to the front line, where they kept HQ apprised of developments. The BPS was so highly regarded that a Belgian Army officer—who just so happened to be an American citizen—was dispatched to help the Americans set up their own pigeon service after they’d arrived in Europe.

To answer the question posed earlier in this blog, all facts demonstrate that the BPS performed extraordinarily well in the face of incredible hardships. The pigeons provided crucial communication and surveillance services under wartime conditions, which undeniably aided the Belgian Army. The resiliency of Belgian fanciers and servicemembers must also be recognized. Despite every effort by the German military to dismantle the BPS, courageous Belgians risked life and limb to train pigeons for war service. The Monument au Pigeon-Soldat, a statue in Brussels commemorating the bravery of Belgium’s pigeons and citizens during World War One, serves as a fitting tribute to the BPS.

Sources:

- Baynes, Ernest Harold, Animal Heroes of the Great War, at 226-227 (1925).

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 244 (1901).

- “Fleet Pigeons Used By Warring Forces to Reveal Enemy’s Secrets,” The Buffalo Sunday Morning News, Nov. 8, 1914, at 22.

- Fox, Frank, The Agony of Belgium, at 246 (1915).

- Kistler, John M., Animals in the Military, at 224 (2011).

- Marion, Henri, Report on Homing Pigeon System, at 11-12 (1897).

- Massart, Jean, Belgians Under the German Eagle, at 147 (1916).

- Naether, Carl A., The Book of the Racing Pigeon, at 55-56 (1944).

- Osman, Alfred Henry, Pigeons in the Great War, at 50 (1928).

- “Pershing’s Men Train Pigeons to Carry Notes,” The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer, Oct. 27, 1917, at 5.

- “Resourceful Belgians,” The Age, Aug. 17, 1914, at 7.

- Whitlock, Brand, Belgium Under German Occupation, at 183 (1919).

- “With the Belgian Army: The Carrier Pigeon Service,” The Illustrated War News, May 16, 1917, at 30.

Home