On January 27th, 1871, three homing pigeons floated out of Paris on the manned balloon Le Richard Wallace. These birds had been tasked with the solemn duty of carrying messages from central France into the besieged city. Yet this would be the final mission of the Paris pigeon post; city officials would sign an armistice with the Prussians the very next day. Although it had lasted for only four months, the pigeon service had inspired the world, showing that communication could be maintained in wartime. In the wake of the Franco-Prussian War, the Great Powers of Europe scrambled to stock their militaries with pigeons. Which country would be the first to win this arms race over carrier pigeons?

Surprisingly, the Russian Empire—a country viewed by many as being hopelessly stuck in the Middle Ages—beat all of them to the chase. In April 1871, just two months after the Paris pigeon post had ceased functioning, Russian officials approached Victor La Perre de Roo—the French fancier who had convinced the Parisian government to use pigeons—about setting up a military pigeon system in Russian Poland. Roo turned them down, but he did advise the Czar’s ministers on the basics of setting up a pigeon service for the Army. A service soon was established between St. Petersburg, the imperial capital, and Krasnoye Selo, a town that hosted annual military maneuvers. Lofts quickly popped up all across the Empire, with stations in the capitals of modern-day Poland and Ukraine.

These early lofts faced setbacks. In spite of great expense, the pigeons’ performances failed to live up to expectations, leading to the shuttering of some lofts in 1883. Military authorities blamed the pigeons and the Russian landscape. The native stock of birds evidently was ill-suited for long flights, while the imported pigeons could not tolerate the Arctic climate, dying in large numbers. Meanwhile, the countryside was so “uniform and monotonous, that the birds had no landmarks to guide them, and consequently were very often lost.” It was also asserted that the service had been poorly organized and run by amateurs.

To remedy these issues, the service was placed under the aegis of the Army’s Engineering department. Gradually, a cold-hardy bird capable of long-distance flights was developed by selectively breeding for these traits in foreign pigeons. Through trial and error, four strains emerged as the clear winners: the English carrier pigeon and the Brussels, Antwerp, and Liege varieties. Funding for the stations also increased significantly, as thousands of rubles were allocated annually for their maintenance.

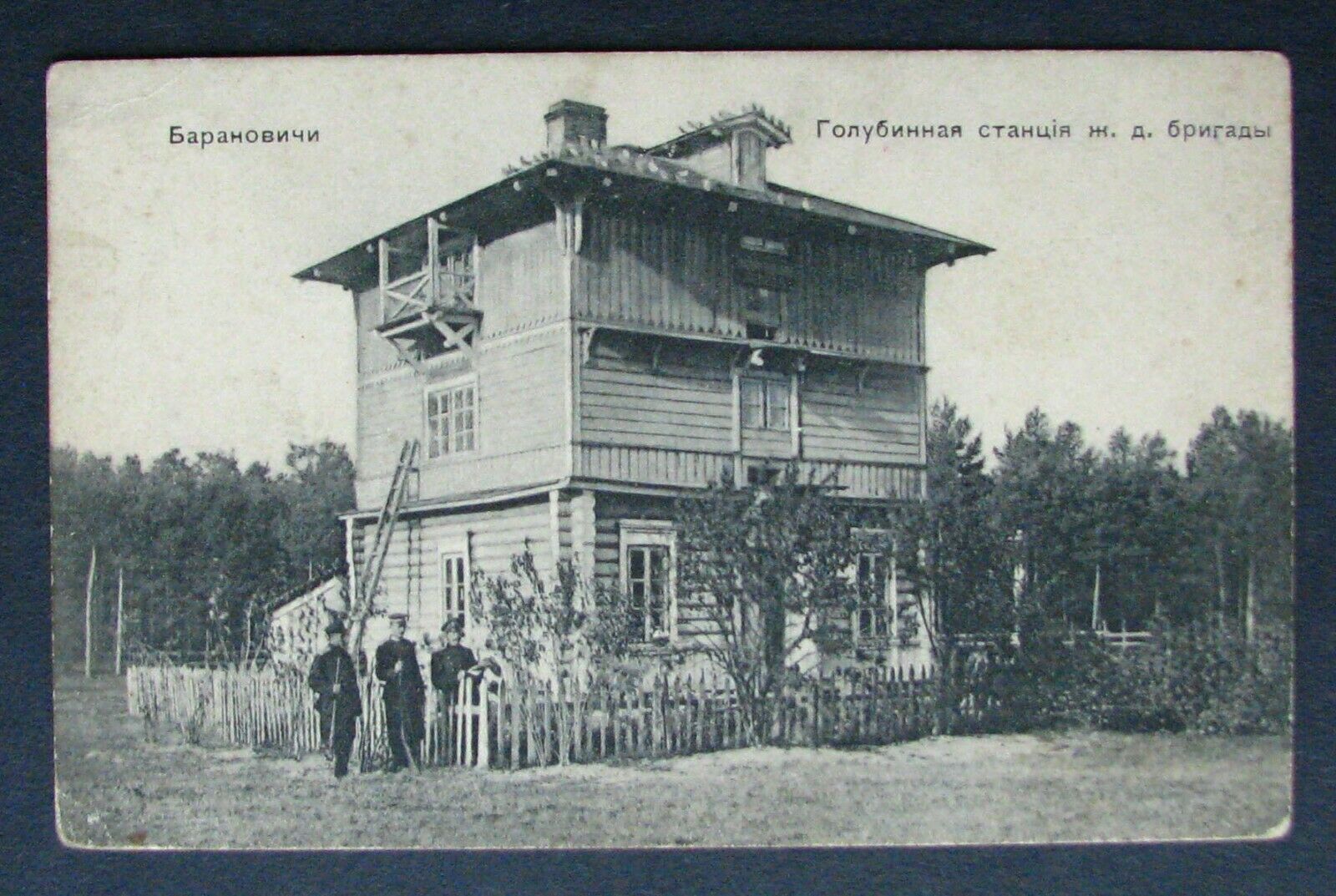

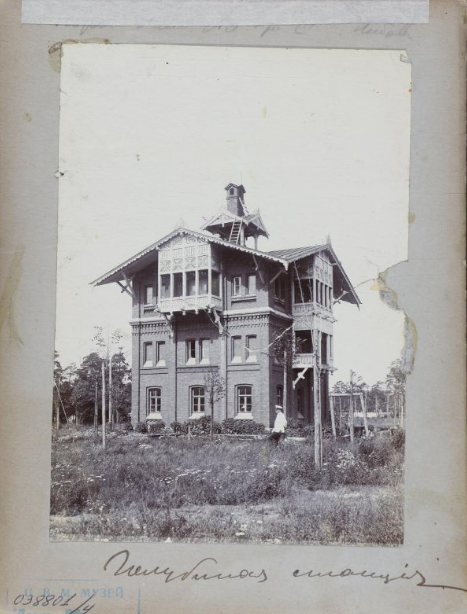

Following these improvements, the pigeon stations of the Empire’s western territories flourished. At first, the service was confined to Polish and Belorussian fortresses. A lieutenant-colonel, supported by a staff of officers, trainers, and servants, oversaw operations. Forts at Warsaw, Novogeorgiesvsk (Modlin), Ivangorod (Deblin), Luninets, and Brest-Litovski (Brest) kept lofts, allowing for communication amongst them. The amount of pigeons at each loft depended upon how many forts were within the birds’ flight paths. The Brest-Litovski loft, for instance, needed pigeons trained to fly in four different directions, as it was situated centrally amongst the five forts. The loft accordingly harbored the most birds, serving also as a breeding depot. By 1891, the lofts housed 3000 birds.

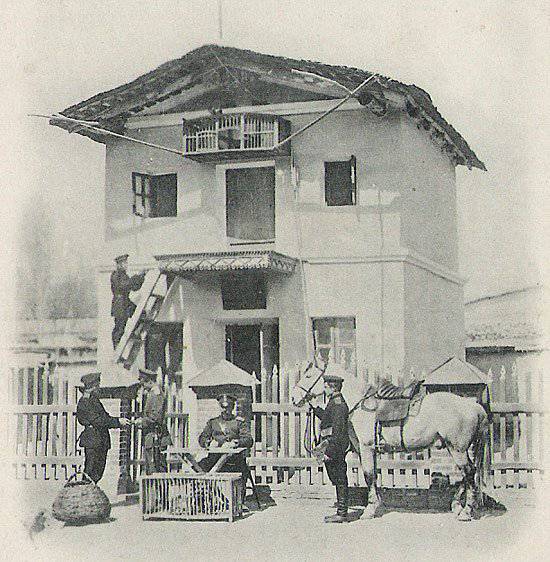

The success of these pigeon stations prompted the Czar to issue ukases calling for more lofts. Additional lofts were built in Poland, while forts in present-day Latvia, Lithuania, and Ukraine adopted their own pigeon services. With this expansion, the military began exploring other ways in which the pigeons could be utilized. The Libau (Liepaja), Sevastopol, and Odessa stations, which were headquartered at naval bases, trained their birds for maritime service. These birds relayed messages from outgoing warships to the forts. Officials also experimented with outfitting cavalry troops with pigeons, which would allow them to send dispatches back to HQ while out in the field. Preliminary trials showed that the birds could deliver messages in one-fifth of the time it took a mounted orderly to do so. Such a service would be especially ideal for scouts exploring terrain unsuited for telegraph service. In Russian Turkestan, an enterprising lieutenant stationed in Tashkent trained pigeons for this express purpose. When his brigade set up camp twenty-one miles away while on maneuvers, their pigeons delivered 228 messages to the base over four months.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, the Russian military felt confident to deploy its pigeons in a massive war game planned for September 1902. Designed to be “on a scale of magnificence unequaled in the history of European manoeuvers,” the games would simulate attacks on Moscow and Kursk, pitting two armies of 150,000 soldiers against one another. Each army was directed to equip their cavalry with pigeons and transmit any gathered intelligence to the higher-ups via telegraph. By all accounts, the pigeons’ performances were “satisfactory and useful.”

The pigeons had fared well under simulated wartime conditions. But how would they measure up in an actual conflict? An answer would soon be forthcoming in the Russian Far East.

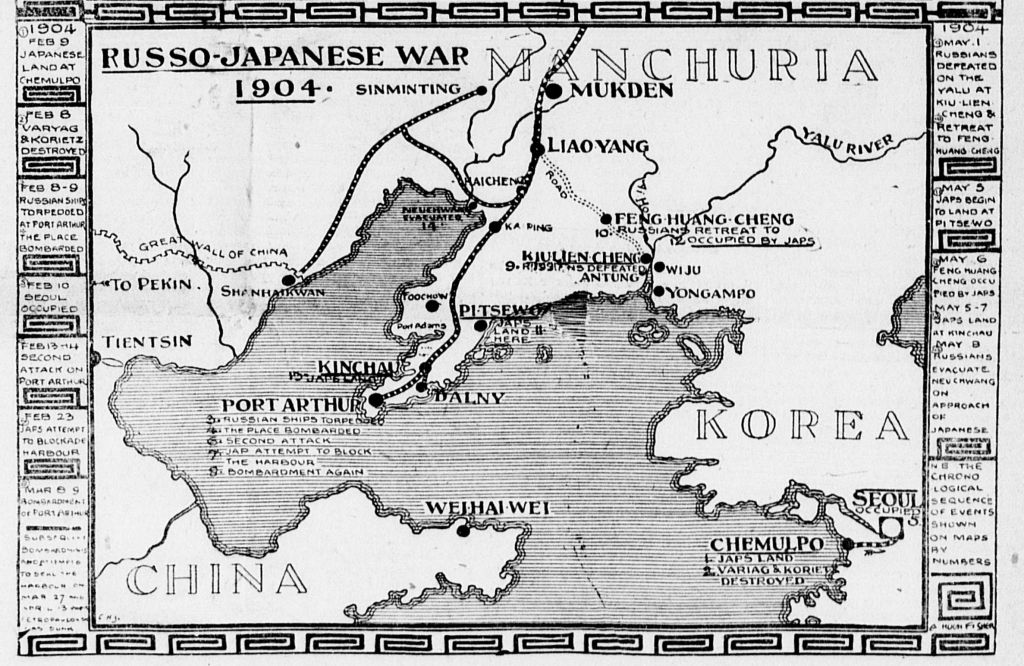

In the closing years of the nineteenth century, the Empire had gained a foothold in Northeastern China, establishing outposts throughout Manchuria. In 1898, Russia obtained a lease of Port Arthur, a natural harbor on the southern tip of the Liaodong Peninsula, from China, intending to use the site as its only warm-water port on the Pacific coast. In fortifying its Manchurian possessions, the Russians made sure that each one contained a military loft. Japan resented Russian encroachment into its sphere of influence. The two countries tried to mediate their issues for several years, but nothing came of it. On February 8, 1904, the Japanese Navy suddenly attacked the Russian fleet at Port Arthur without warning. War was declared shortly afterwards.

The Japanese Army launched an all-out assault against Port Arthur. Telegraph lines and railways were destroyed to isolate the Port. Fortunately, the Port had a fledgling pigeon post in place. Within days of the War’s start, a French colombophile society had approached Port Arthur about setting up a pigeon service for communicating with other districts in Russian-controlled Manchuria. Officials immediately accepted the offer. Pigeons from strategic Manchurian cities were collected and sent to Port Arthur, while the Port’s birds were shipped out to those areas. Such a system, in theory, would allow for two-way communication to be sustained.

For the next several months, Port Arthur relied on its pigeon post for communicating with the outside world. In May, pigeons carried status reports to the Manchurian Army’s headquarters in Liaoyang and delivered positive news to Mukden (Shenyang) that two Japanese battleships had struck mines outside the Port’s harbor. In June, Chefoo (Yantai) and Newchang (Yingkou) received updates from the Port’s commander, General Anatoly Stessel. These seem to be the only substantive messages received from the Port. Attempts at contacting the Port were likewise fraught with difficulty. Russian authorities had arranged for Chinese junk boats to ferry Port Athur’s birds across the Yellow Sea to Chefoo for espionage work. Agents in the employ of Russia were instructed to gather information about the Japanese fleet and send it by pigeon. Only one of these pigeons made it back to Port Arthur. Meanwhile, at Liaoyang, the Manchurian Army had built a special station to house the Port’s pigeons, but only three of them ever returned. The failure of so many pigeons to home successfully may stem from the Japanese Army’s recruitment of hawks to intercept them.

In spite of the difficulties experienced during the Russo-Japanese War, the Russian Empire continued to maintain its pigeon stations, even building a “first-class station with 1000 pigeons” at the naval base in Vladivostok. On the eve of the Great War, Russia boasted ten military pigeon stations stretched across both ends of the Empire. When hostilities commenced in 1914, the Sevastopol station proved its worth when one of its birds alerted the fortress that the Turkish battlecruiser Yavuz had the city within its sights. A Russian destroyer had spotted the enemy vessel and tried warning the fort, but the ship’s radio failed. Thankfully, sailors found one of Sevastopol’s birds on board the ship and released it with news of the threat. Further information on how the pigeon service assisted Russians during the War is scarce, but they undoubtedly facilitated communication between forts and aided reconnaissance activities. The stations would not survive the War, however. As Russian forts along the Eastern Front fell, their pigeons were evacuated along with the troops. On March 23th (April 5th), 1916, the Czar’s government shut down the Empire’s three remaining pigeon stations. The birds were shipped to a newly formed military pigeon depot in an effort to preserve the stock while the War persisted.

After 45 years, the Russian Empire’s pigeon stations were no more. Yet memories of the birds’ unique capabilities persisted within military circles, even after the Soviet Union had risen from the Empire’s ashes. Soviet military brass began incorporating pigeons into aircraft exercises during the mid-’20s. In 1928, the Deputy People’s Commissar of the USSR for Military and Naval Affairs recommended that the armed forces adopt a pigeon service. At the start of the Great Patriotic War, the Red Army boasted over 250 pigeon stations with 30,000 pigeons. These stations would prove their merit in battles against the Germans. But that’s a story for another day.

Sources:

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 123-24, 130-31 (1888).

- “An Unintelligible Message,” Manchester Evening News, May 11, 1904, at 2.

- “Carrier Pigeons for Port Arthur,” The Evening Mail, Feb. 23, 1904 at 10.

- “Carrier Pigeons in Service,” Palladium-Item, June 6, 1904, at 3.

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 240 (1901).

- Department of Marine, “Report on Messenger Pigeons,” Twenty-Third Annual Report of the Department of Marine, for the Fiscal Year Ended 30th June, 1890, at 205.

- Egorov, Boris. “How Pigeons Helped the Red Army to Win in World War II.” Russia Beyond, 8 Dec. 2021, https://www.rbth.com/history/334499-how-pigeons-helped-red-army

- “From the Besieged,” Herald and Review, Jun. 5, 1904, at 1.

- “Meek Spies.” Военное Обозрение, 22 Oct. 2015, https://en.topwar.ru/84473-krotkie-shpiony.html

- “Military Pigeon Post at the Kursk Maneuvers,” Journal of the United Service Institution of India, Vol. 32, 1903, at 277.

- “Pigeons in the War: Japanese and Russian,” Black & White, Vol. 27, June 18, 1904, at 914.

- “Pigeon Post Sea Station in Karosta.” Military Heritage Tourism, Interreg Estonia-Latvia, https://militaryheritagetourism.info/en/military/sites/view/460?0

- “Port Arthur,” Manchester Evening News, May 11, 1904, at 2.

- “Port Arthur and Mukden,” Liverpool Daily Post, May 11, 1904 at 5.

- “Russia – Army Maneuvers,” Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Vol. 6, No. 2, Jul. – Dec. 1902, at 1366.

- “Russia is Rejoicing,” Albine Weekly Reflector, May 26, 1904, at 12.

- Schuyler, Walter, S., Reports of Military Observers to the Armies in Manchuria, Vol. 1, at 154 (1906).

- Sergeev, Evgeny, Russian Military Intelligence in the War with Japan, 1904-05, at 95-96 (2007).

- Toepfer, Capt. “Technics in the Russo-Japanese War,” Professional Memoirs, Corps of Engineers, United States Army, and Engineer Department at Large, Vol. 2, No.6, at 191 (1910).

- “Train Falcons for War Use,” Lancaster Teller, Mar. 2, 1905, at 6.

- “Will Play War in August,” Nashville Banner, Jun. 11, 1902, at 1.

- Историческая Справка По Станциям Военно-Голубиной Почты., http://www.antologifo.narod.ru/pages/list/histore/istPostG.htm

- ВОЙНА И ГОЛУБИ.ВОЕННО , Live Internet, https://www.liveinternet.ru/users/4768613/post351439272/#

One response to “The Russian Empire’s Pigeon Stations: 1871 – 1916 A.D.”

[…] View Source […]

LikeLike