Many of the famed war pigeons we’ve discussed at Pigeons of War were maimed in battle. This is not surprising, given that the birds served in active war zones. As visible targets flying over enemy lines, pigeons frequently lost legs, eyes, and wings. But some pigeons manage to remain injury-free in war. This week, we look at one such pigeon—Spike. Despite serving in dozens of missions during World War One, he allegedly was never injured.

Spike was born in France around 1917 or 1918 in a loft under the care of the United States Army Signal Corps. Of uncertain parentage, he possessed a grey “grizzle” coat and wasn’t much of a looker. But his trainers soon realized that this unattractive bird possessed myriad talents. “[H]e was a strong, aggressive, fast-flying bird with considerable vitality and unusual endurance,” an observer reflected after the War.

Having passed his training regimen with flying colors, Spike was assigned to service in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive in the fall of 1918. He wasn’t the only pigeon there—90 percent of the Signal Corps’ birds served in this campaign, which featured some of the bloodiest fighting in the War. Spike rode along in the Army’s tanks, flying important messages to the American HQ. He quickly set a record flight time of traveling 20 kilometers in 21 minutes. His speed, however, was the least of his abilities. In completing over 52 missions during the Meuse-Argonne campaign, Spike remained injury-free, despite flying through torrents of gunfire and artillery shells. Or at least that’s what the legend says. A newspaper account of Spike’s deeds published in the summer of 1919 claimed that he was gassed near Sedan, France on the day before the War ended.

Whether Spike was injured or not, Army officials nonetheless credited the bird with stellar service. “This bird has probably rendered more efficient service than any other pigeon used in the war,” the Assistant Secretary of War wrote in Spike’s official wartime citation. Seeing an opportunity to create a public interest in the Army’s pigeons, General John J. Pershing issued an order requesting that Spike and other special war pigeons be sent to the United States for public exhibition. Spike boarded the troop transport ship Ohioan and arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey on April 16th, 1919. He was sent to a special Army loft for distinguished military pigeons in Potomac Park in Washington, D.C., where he joined President Wilson, Cher Ami, Mocker, and around 20 other pigeon war heroes. Open to the public, the loft allowed the pigeons to live a life of ease—food was provided and they were not expected to work, aside from daily flight exercises.

After a few years at the Potomac Park loft, Spike, President Wilson, and Mocker were sent to Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, the headquarters of the Signal Corps’ pigeon program. The three of them were “kept in the cleanest, airiest of lofts” and “fed the choicest canary seed, rice and Canadian peas.” They also contributed to the Army’s breeding program by providing their superior genes. Indeed, one of Spike’s progeny, a pigeon named Sunnybrook, won several civilian pigeon races. Even in his later years, Spike remained feisty. In 1933, he picked a fight with Rheingold, a German pigeon captured during the War, over a nesting bowl in the central breeding and training lofts. Owing to the birds’ advanced ages, their trainer was able to break them up before the quarrel turned truly nasty.

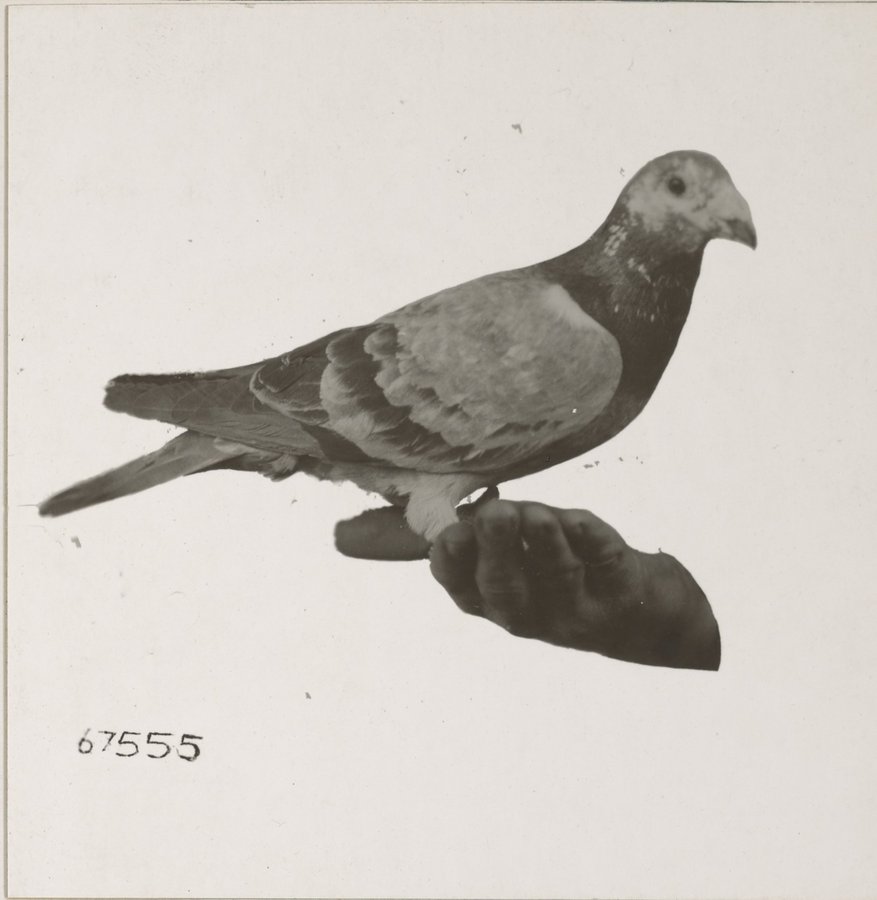

After a lengthy retirement, Spike passed away on April 11, 1935. At 17, his death was attributed to natural causes. Thomas Ross, the Army’s resident pigeon keeper, noted the impact Spike’s passing would have on Mocker. “Oh, they were always scrapping, but Mocker, he’ll miss Spike.” His body was stuffed by a local taxidermist and sent to the office of the Chief Signal Officer in Washington, D.C for public display. These days, Spike can be viewed at the US Army’s Center of Military History.

Considering his heroism during the Great War, Spike should be as well known as Cher Ami. Unfortunately, that’s not the case. Unlike Cher Ami, there are no movies or books celebrating his wartime service. We at Pigeons of War feel this is a deplorable state of affairs–Spike was a hero and should be recognized as such.

Sources:

- Blazich, Frank A. “Feathers of Honor: U.S. Army Signal Corps Pigeon Service in World War I, 1917–1918.” Army History, No. 117 at 45-47.

- Bryant, H. E. C., “Pigeon Heroes to Be Honored,” The Charlotte Observer, Apr. 16, 1919, at 9.

- “Crippled Pigeon May Be Awarded D.S.C.,” The Evening Star, Apr. 17, 1919, at 2.

- “Death Whittles Ranks of War’s Pigeon Aces,” The Journal, Jul. 29, 1929, at 6.

- Doran, Dorothy, “Pigeons and People,” The Long Branch Daily Record, April 14, 1933, at 6.

- “Famed Army Pigeon Dead,” The Times-News, Apr. 13, 1935, at 6.

- Haskin, Frederic J., “The Pigeon’s Service,” The South Bend Tribune, July 26, 1919, at 10.

- “A Lone Survivor,” The Billings Gazette, May 1, 1935, at 4.

- Miller, James N, “The Passing of the Carrier Pigeon,” Popular Mechanics, Vol. 53, No. 2, Feb. 1930, at 194.

- “War Bird Heroes on Visit to City,” The Starry Cross, Vol. 28, No.4, April, 1919, at 92.