-

Pigeons in the Siege of Antwerp, 1832

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 is perhaps the most well known instance of pigeons being used to carry information in and out of a city during a siege. But nearly 40 years earlier, the Dutch military used pigeons in a similar fashion during the Siege of Antwerp in 1832. In this post, we examine the role of pigeons in that conflict.

In the summer of 1830, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands witnessed a series of revolts in its southern provinces, an area comprising modern-day Belgium. Religious differences played a significant role: The Belgian provinces were primarily inhabited by Roman Catholics, while the northern Dutch provinces were dominated by Protestants. The Belgians also despised their lack of autonomy and underrepresentation in the Netherlands’ General Assembly. Inspired by the July Revolution in France, revolutionaries in Brussels took over the city in August and declared their independence from the Dutch King William. The uprising quickly spread to other cities in the Belgian Provinces over the ensuing weeks.

On September 23rd, Prince Frederick, the Commander-in-Chief of Dutch forces in Belgium, hoped to quell the rebellion by seizing Brussels from the revolutionaries. Facing fierce street fighting, the Prince withdrew his troops after four days and retreated to Antwerp. The choice of Antwerp seemed logical at the time. The city had remained loyal to the Dutch government. Moreover, Antwerp boasted extensive fortifications in its southern area. The centerpiece was the Citadel, a pentagon-shaped bastion fort situated in front of the Scheldt River. It could host thousands of soldiers and featured 114 pieces of artillery. Across the river, the Flemish Head and several other minor forts also contributed to the city’s defense, while also serving as ports for the Dutch Navy’s warships.

But as the month of October progressed, revolutionary fervor swept over Antwerp. General David Chassé, the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief and a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, ordered his troops to take refuge in the Citadel. To protect the fort, the Dutch government dispatched several frigates and gunboats to implement a blockade on the Scheldt. Dutch naval officer Captain Jan Koopman was tasked with serving as a liaison between the fleet and the Citadel. On October 25th, Antwerp fell to Belgian insurgents, while the Citadel remained under Dutch control. A ceasefire was brokered between the revolutionaries and the Dutch troops, but the former broke it when they tried to seize an arsenal. In retaliation, the Citadel and the Dutch warships bombarded Antwerp until the Belgian insurgents withdrew from the town into the suburbs. The parties eventually entered into an uneasy truce, with General Chassé to remain at the Citadel until he received orders from King William to yield.

With the Citadel and the Dutch flotilla now surrounded by an unfriendly population, military officials needed a proper communication network to ensure the flow of information in and out of the garrison. A mail barge allowed for correspondence to be delivered to and from the Citadel, but this method was time consuming. For urgent messages, a different medium had to be found.

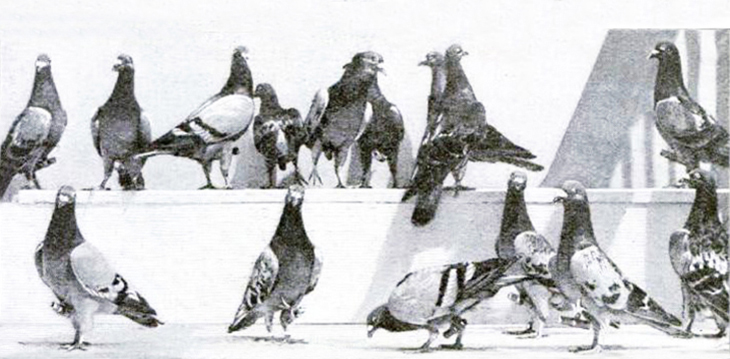

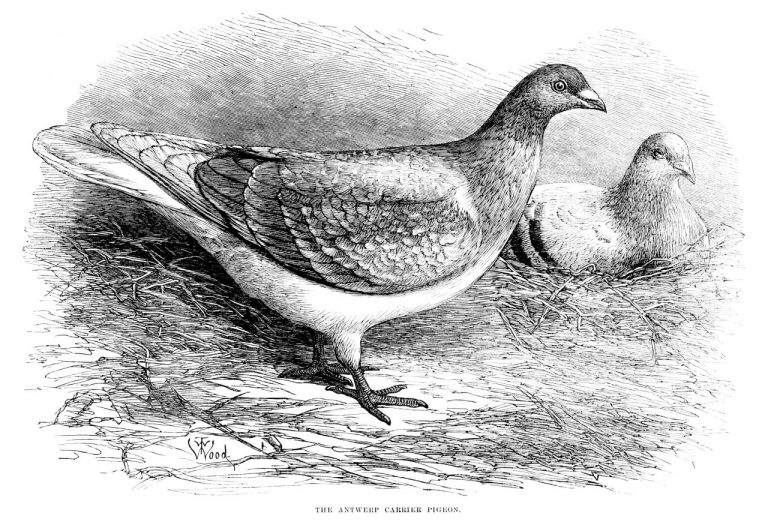

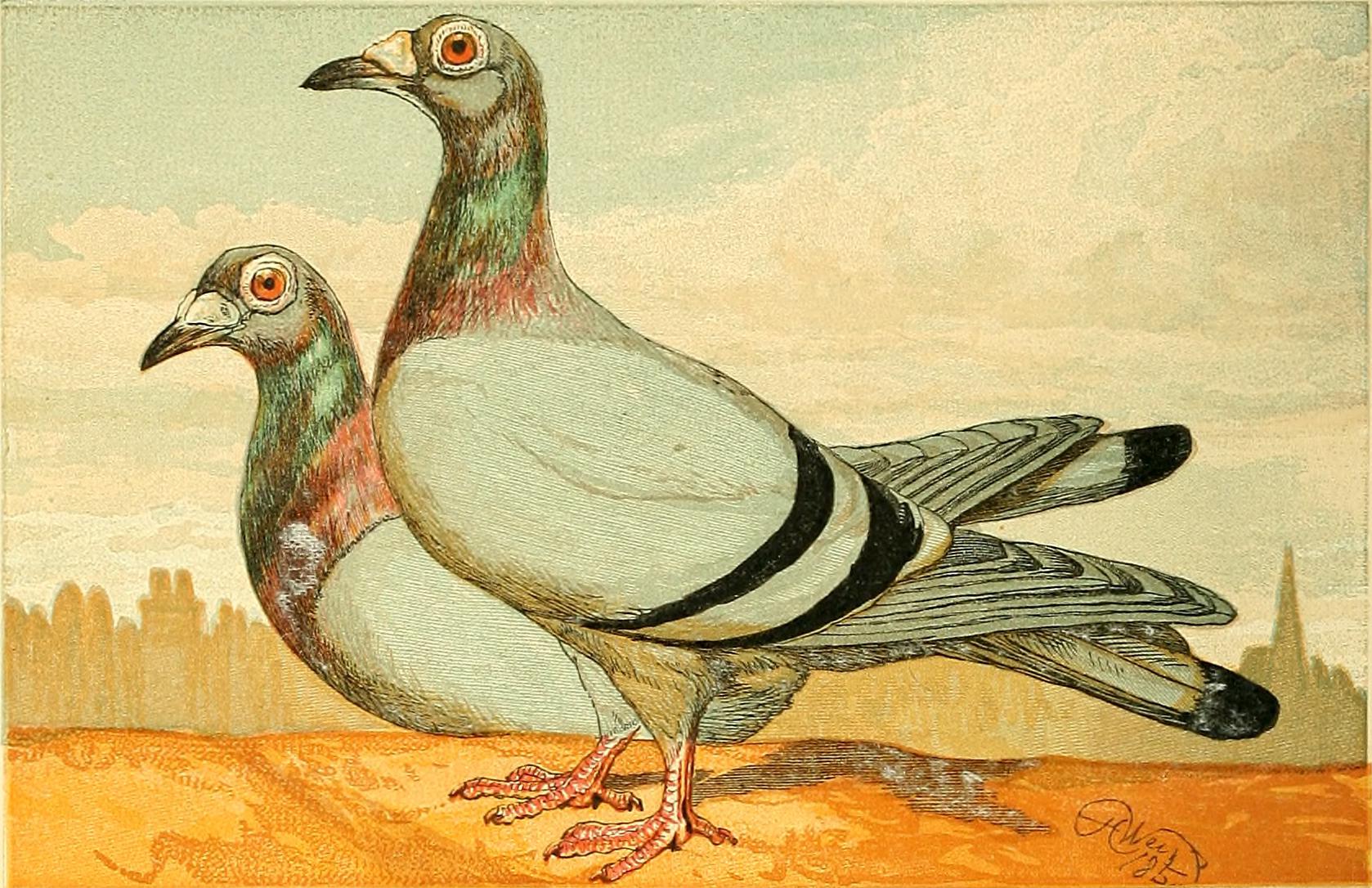

Fortunately for the garrison, pigeon racing was a popular pastime in Antwerp. Numerous pigeon clubs flourished within the city and they competed against each other at an annual competition. Fanciers even had developed a unique variety of pigeon known as the Antwerp carrier, a fusion of three breeds: the Smerle, the Cumulet, and the Dragoon. An ancestor of the modern Belgian racing homer, the Antwerp Carrier was renowned for its flight abilities and stamina. In 1819, one Antwerp pigeon flew 180 miles from London in six hours, a remarkable speed for the era. Beyond participating in sport, Antwerp Carriers had been put to commercial use; a 1824 newspaper account detailed their use in carrying stock price information from Paris to Antwerp, “ten hours earlier than any other couriers could convey them.”

Naturally, the Dutch garrison turned to pigeons to solve their communication issues. A loft was quickly erected on the site of the Citadel. By the winter of 1831, the pigeons were already delivering messages to the Citadel; a contemporaneous newspaper account observed that “a pigeon had been seen flying into the Citadel “traveling from a western direction over the Scheldt River,” bearing “important despatches to General Chassé.” At the same time, Captain Koopman, now serving as the commander of the blockade ships, entered into an agreement with two loyal Antwerp residents to establish a pigeon post that would allow the Captain to be constantly informed “of everything that might happen in rebellious Belgium.” He installed a loft in the upper room of the Flemish Head and employed a young man to catch the birds as they arrived and hand them over to him. To distribute the birds to his network of spies, Captain Koopman arranged for the pigeons to be placed in covered baskets at agreed-upon locations throughout the city. Through this method, Koopman received letters from spies out in the field as well as copies of Belgian newspapers. In a post-war memoir, he claimed information gleaned from his pigeon network prevented several assassination plots against General Chassé and himself from being carried out.

Over the next two years, the Great Powers of Europe tried to resolve the tensions brewing between Belgium and the Netherlands. They recognized Belgium as an independent kingdom on January 20, 1831, in spite of King William’s opposition. On August 2, 1831, he invaded Belgium, shortly after it had crowned its new monarch, King Leopold I. Upon the intervention of the French, however, King William agreed to an armistice, but refused to order an evacuation of the Antwerp garrison.

A whole year passed before the Great Powers acted to enforce Belgium’s sovereignty. On November 4, 1832, an Anglo-French fleet blockaded the Dutch coast, while a French army comprising 56,000 men headed toward Antwerp. On November 30th, the French army demanded Chassé’s surrender. Even though the General had only 5000 men under his command and had been informed by his superiors that no aid would be sent from the Netherlands, he refused to stand down. The French prepared for a siege by digging trenches before the Citadel. By the start of December, their guns were in place, including a new, terrifying weapon: the monster mortar, a 24-inch caliber gun. On December 4th, the French began bombarding the Citadel.

Throughout the siege, the Dutch depended heavily upon their pigeon network. Indeed, the network had recently expanded to include areas beyond the Citadel and the Flemish Head. Just before the start of the siege, “a great number of emissaries with pigeons” had been sent from the Netherlands to areas surrounding Antwerp. From Antwerp, the pigeons could send intelligence to Dutch forces in Breda and Bois-le-Duc. To combat the spread of information through pigeons, French military authorities in Antwerp required that all pigeons brought into the city have their wings clipped.

Amidst the constant bombardment, the pigeons performed their task admirably. “It is singular,” remarked a journalist covering the siege, “that, notwithstanding the noise and smoke, the pigeons employed at Antwerp as carriers were flying about in the very thick of it.” Thanks to their efforts, General Chassé received frequent updates of news from the outside and “remained in constant communication with [the] government.” Captain Koopman ,too, noted that in spite of “the incessant thunder of all kinds of artillery,” his pigeons “flew regularly to me, and brought me, among other things, daily reports of the losses suffered on the side of the enemy.” On December 13th, the Captain received a message alerting him of French plans to attack an outer defense fort. As late as December 20th, pigeons were still flying messages from the city and the Dutch flotilla to the Citadel.

Over the next two days, the French deployed the monster mortar against the Citadel with devastating effect. With much of the Citadel’s walls in ruins, General Chassé surrendered on the morning of December 23, 1832. Belgium and the Netherlands were now de facto separate states, although King William refused to officially recognize the Kingdom until 1839, following pressure from the Great Powers.

The 1832 Siege of Antwerp is the first recorded military use of pigeons in 19th century Europe. A relatively obscure conflict, it undoubtedly laid the foundation for the use of pigeons in the Franco-Prussian War nearly forty years later. It is a shame that the role of pigeons in the siege has been little studied to date.

Sources:

- “Antwerp,” The Examiner, Dec. 2, 1832, at 8.

- “Belgium,” The Vermont Gazette, Mar. 1, 1831, at 2.

- “Belgium and Holland,” The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser, Dec. 29, 1832, at 2.

- “Belgium and Holland,” The Standard, Dec. 10, 1832, at 2.

- “Bombardment and Capture of Antwerp,” Arkansas Times and Advocate, Jan. 26, 1831, at 2.

- “Carrier Pigeons,” Springfield Weekly Republican, Oct. 6, 1824, at 4.

- Claflin, Harold W., The History of Nation: Holland, Belgium, and Switzerland, at 296-303 (1906).

- Harrisburg Chronicle, Sep. 27, 1824, at 2.

- Koninklijk Nederlands Legermuseum. “Het beleg van de Citadel van Antwerpen in 1832,” (2006), available at https://web.archive.org/web/20110724160359/http://www.collectie.legermuseum.nl/sites/strategion/contents/i004551/arma17%20het%20beleg%20van%20de%20citadel%20van%20antwerpen%20in%201832.pdf

- Koopman, J.C., Zijner Majesteits Zeemagt voor Antwerpen, 1830-1832, at 38-39, 104 (1853).

- Martinet, Andre, La Seconde Intervention Française et Le Siege D’Anverse, 1832, at 237-38, 266 (1908).

- Naether, Carl, The Book of the Racing Pigeon, at 95 (1950).

- The Morning Post, Nov. 12, 1832, at 2.

- “The Siege of Antwerp in 1832”. The United Service Magazine, First Part of 1833, at 289–392.

-

Pigeons in the Hut Tax War of Sierra Leone, 1898

When did the British Army first use pigeons in combat? World War One? The Boer War? The answer is the Hut Tax War of 1898, a relatively obscure colonial uprising in Sierra Leone. This week, we take a look at how the British Army, for the first time ever, relied on pigeons to communicate with a distant headquarters.

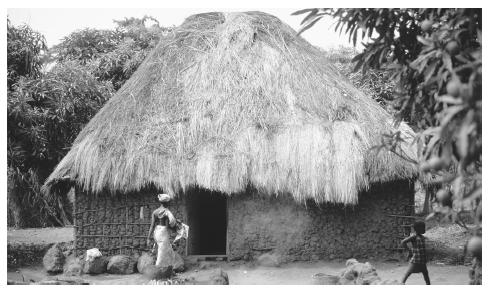

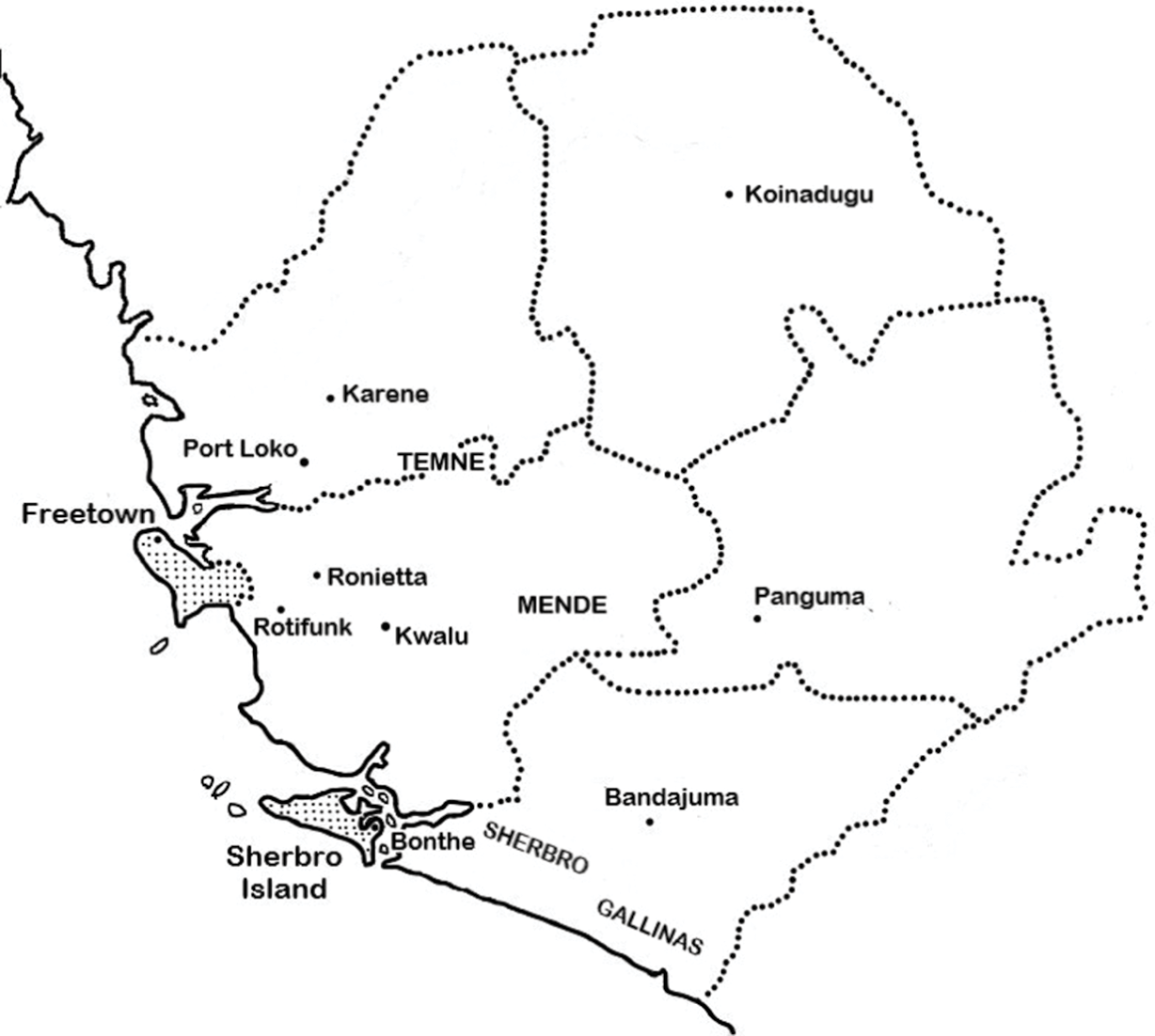

On August 31, 1896, British colonial authorities in the Crown Colony of Sierra Leone unilaterally declared the interior surrounding Freetown a Protectorate. Divided into five districts, the Protectorate encompassed numerous chiefdoms, many of which had no direct treaties or relations with the British government. To consolidate British rule over them, the colonial government issued the Protectorate Ordinance that same year, aimed at encroaching upon the chieftains’ sovereignty. The Ordinance transferred much of the chiefs’ traditional judicial powers to British District Commissioners. It undermined the internal slave trade—a primary source of income for chiefs—by granting enslaved persons the opportunity to obtain freedom by petitioning British officials in Freetown. Finally, the Ordinance implemented a tax on dwellings within three of the Protectorate’s districts, Ronietta, Bandajuma, and Karene. Dubbed the Hut Tax, it required all residents to make payments based on the size of their residence at the start of 1898.

The British also installed Frontier Police posts across the chiefdoms, composed of indigenous men led by British officers. Tasked with ensuring safe passage over roads and keeping the peace, members of the Frontier Police occasionally overstepped their jurisdiction and “interfered in local disputes,” acting as “little judges and governors.” Moreover, much of the Frontier Police had been runaway slaves who had obtained their freedom in Freetown. Chiefs bristled at the prospect of being arrested by their former slaves.

Many chiefs within the Protectorate opposed these measures, the most notable of whom was Bai Bureh. A member of the Temne ethnic group, Bai Bureh had been appointed chief of Kasseh, “a small chiefdom on the left bank of the Small Scarcies River,” in the Karene District in 1887, thanks to his military prowess. While Kasseh was a tiny chiefdom, Bureh possessed considerable authority owing to his status as a kruba or war chief. “There were very few war chiefs,” a historian has noted, “and only they possessed the right to request permission from other chiefs to travel though their chiefdoms to collect armed followers.” Karene’s District Commissioner claimed that war chiefs “were the only ones who possessed any ‘real authority’ and that one of them was worthy fifty ordinary chiefs.”

Bureh had a complicated relationship with the colonial government. He’d been arrested in 1891 for defying a British official, escaping while en route to Freetown. The next year, though, he joined in a colonial expedition against the town of Tambi. After another arrest attempt in 1894, Bureh largely ignored the British until the enactment of the Protectorate Ordinance. In 1897, he joined 24 other chiefs in submitting petitions to the Colony’s governor, Sir Frederick Cardew, protesting the Hut Tax.

Disregarding the chiefs’ opposition, colonial authorities set out to collect the tax in the Karene District in January 1898. They encountered resistance in Port Loko, “the largest and wealthiest town” in the area, and arrested the primary chief and his sub-chiefs in response. Rumors soon emerged that Bai Bureh was planning an attack on Port Loko, resulting in most of the town’s inhabitants fleeing. On February 16th, a detachment of Frontier Police set out from Port Loko to Karene to find and arrest Bai Bureh. On the road to Karene, the unit was continually harassed by Bai Bureh’s warboys, who jeered at the Frontier Police and pelted them with stones. At one point in the expedition, the parties exchanged gunfire. The Frontier Police found Karene safe, but remained concerned over the safety of the Port Loko-Karene route; most of the surrounding towns and villages had cleared out in support of the revolt.

Upon receiving word of the Frontier Police’s plight in Karene, Cardew opted for a demonstration of British power. On February 22nd, Cardew ordered a company of the 1st Battalion West India Regiment (WIR)—an Army infantry unit composed of recruits from British Caribbean colonies—to head to Karene. Commanded by Major Richard Joseph Norris, the WIR company’s primary mission was to set up a garrison at Karene, allowing the Frontier Police to pursue Bai Bureh. If necessary, the company was authorized to support the Frontier Police in case of an attack, but Cardew hoped that “once the troops arrived, resistance to the administration’s authority would collapse.”

A particular challenge facing the WIR at Karene would be maintaining contact with Freetown, which was 60 miles away. All lines of communication between Port Loko and Karene had ceased on February 19th after supporters of the rebellion stole the Frontier Police’s canoes. Cut off from Porto Loko, the Frontier Police in Karen had no way of communicating with Freetown, absent a circuitous, northwestern route. Fortunately, Thomas Chadwick, a merchant with the trading firm G.B. Ollivant and Company, came up with a solution. Having represented the firm’s interests in Freetown since 1891, Chadwick had been frustrated that “communication with the interior could be conducted only by runners.” He’d imported a loft of homing pigeons from England and trained the birds to deliver news from the interior to Freetown. The pigeons had allowed Chadwick to be “always better informed than any of his competitors regarding the position of produce stocks and merchandise requirements.” Seeing the administration was in a bind, Chadwick turned his pigeons over to the government for use in Karene.

The WIR company departed Freetown on February 25th aboard a government steamer up the Great Scarcies River and disembarked at a nearby village on the 26th. Norris and his troops marched to Karene, reaching the town unopposed on the 28th, although they were monitored by warboys. The company found the Frontier Police besieged on all sides, with three of its members in the hospital. As the situation in Karene escalated, on March 2nd, the District Commissioner requested that Norris declare martial law and assume responsibility for the administration of Port Loko and Karene, to which Norris assented. The next day, the company marched to Port Loko to restore communication between the two towns. Throughout the 25 mile march, the soldiers encountered intense opposition from Temne warboys, both sides suffering casualties. On March 4th, Norris, fearing that Port Loko would soon be attacked, released a pigeon with a message requesting two additional WIR companies from Freetown. Cardew received the message that same day, but, believing that Norris “could easily hold his own,” sent only one company.

On the evening of March 5th, the second WIR company arrived at Port Loko, only to find the town had earlier been the site of a fierce, four-and-a-half hour battle between Norris’s troops and Temne warboys. As hostilities mounted, Norris continued badgering Cardew for additional WIR companies over the ensuing days until the governor ultimately acquiesced and sent two more. Each unit departing Freetown received twelve pigeons.

By mid-March, the WIR companies had coalesced into a force of 700 troops under the command of a colonel. Now known as the Karene Expeditionary Force (KEF), the forces made Port Loko their headquarters and focused on keeping the road to Karene open. Throughout these patrols, the KEF kept Freetown apprised of developments via pigeon. “[A]uthorities at Freetown knew the position of matters at Port Loko, which is twenty-five miles off, within half-an-hour’s time,” a newspaper reported. On the evening of March 25th, a pigeon brought news to Freetown officials of a reversal suffered en route to Karene:

Things very serious; fifty of the West India Regiment and twenty-seven carriers missing; many wounded, including four officers; Lieutenant Yeld is dead.

Following an attack two days later resulting in 35 casualties and the death of the colonel from “heat apoplexy,” officers concluded that the KEF’s frequent patrols between Port Loko and Karene had resulted in excessive casualties, while the original mission of locating Bai Bureh languished.

On April 1st, the uprising took on a frenzied pace, as a new colonel, John Marshall, took command of the KEF. Under his direction, the troops set up two intermediate outposts along the Port Loko-Karene route to cut down traveling time between the towns. Marshall then implemented “a scorched earth policy in Kasseh country.” “Taking out a flying column each day,” writes one historian, “he razed every village which offered resistance to his advance.” Meanwhile, the KEF continued relying on pigeons to support its operations. “This is our daily means of communicating with the outside world,” a British medical officer noted in an April 4th letter. His letters indicate that the KEF’s pigeons kept Freetown abreast of setbacks and requests for supplies and manpower throughout the month. On April 19th, a pigeon notified Freetown that a major had been shot through the lungs while traveling between Port Loko and Karene.

For supplying pigeons to the troops, Chadwick received an official thanks and payment from the colonial government. However, it was soon revealed that Chadwick had in fact supplied some of Bai Bureh’s forces with 100 lbs gunpowder! Many merchants had actually preferred robust chiefdoms, because they could curry favor with individual chiefs. Incensed at this apparent betrayal, the Secretary of the State for Colonies Joseph Chamberlain initially pushed for the prosecution of Chadwick. But after identifying weaknesses in the case and noting that the Colony had already thanked Chadwick for his services, Chamberlain deemed it prudent to drop the matter.

Marshall’s campaign of destruction paid off—by the end of May, he reported that “[t]he whole of the disaffected areas of the Karene district had been overrun, and the power of the rebel chiefs utterly broken.” The KEF established permanent garrisons in Karene and Port Loko, while the remainder of the forces returned to Freetown on July 10th. The Frontier Police continued their pursuit of Bai Bureh, but he managed to evade capture for months until November 11th, when he was found in “swampy, thickly vegetated country.” Colonial officials spared his life, but exiled him to the Gold Coast, where he remained until he was permitted to return to Kasseh in 1905.

The Hut Tax War of 1898 soon faded from memory—it was just one of many colonial uprisings against the British Empire. But the British Army’s successful use of pigeons in the conflict remained a part of the Army’s institutional memory. During the Boer War, the Army, inspired by Sierra Leone’s example, relied on pigeons for communications during the Siege of Ladysmith in 1899 and 1900. Throughout World War I and World War II, British troops routinely employed pigeons when other mediums of communication were lacking. This long-forgotten war, therefore, merits our attention for conclusively demonstrating to British military officials that pigeons could facilitate communication under wartime conditions.

Sources:

- Abraham, Arthur. “Bai Bureh, The British, and the Hut Tax War,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1, at 99-102 (1974).

- Altham, E.A. Major, The Ladysmith Pigeon Post, The Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Vol. XLIV, No. 273, November 1900, at 1231.

- Clodfelter, Michael. Warfare and Armed Conflicts, at 210 (2017).

- Crowder, Michael, and Laray Denzer. “Bai Bureh and the Sierra Leone Hut Tax War of 1898,” Colonial West Africa, at 61-62, 64, 67, 69, 70-73, 83-88, 91-92, 94-95 (1978).

- Fyfe, Christopher, A History of Sierra Leone, at 579 (1962).

- Marshall, John. “Report, 30 August, 1898, Lt.-Col. Marshall, Commanding Karene Expeditionary Force—Operations in Timini County.” Report by Her Majesty’s Commissioner and Correspondence on the Subject of the Insurrection in the Sierra Leone Protectorate, 1898, at 613-16, 621 (1899).

- “News from West Africa,” The Standard, Apr. 13, 1898, at 3

- Pedler, Frederick, “British Planning and Private Enterprise in Colonial Africa,” Colonialism in Africa 1870-1960: Vol. 4, at 96 (1969).

- Pedler, Frederick. The Lion and the Unicorn in Africa: A History of the Origins of the United Africa Company 1787-1931, at 95-96 (1974).

- “The Disturbances in Sierra Leone,” The Times, Apr. 9, 1898, at 4.

- “The Sierra Leone Revolt,” The Birmingham Post, May 6, 1898, at 10.

- “The Troubles in Sierra Leone,” The African Review, Vol. XV, Apr. 16, 1898, at 96.

- Tobin, Richard. “A Memoir of the Late Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Dalton, R.A.M.C,” BMJ Military Health, Vol. 24, at 76-78, 1915.

- “West African Operations,” The Morning Post, Mar. 24, 1898, at 5.

-

Pigeons in the Arctic: Part III: Sir John Ross’s 1850-51 Search for the Lost Franklin Bay Expedition

We’ve previously written about how Arctic explorers relied on homing pigeons in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Recently, we uncovered facts demonstrating that Royal Navy personnel brought homing pigeons with them as they searched for the Lost Franklin Bay Expedition in the 1850s. Given that homing pigeons were very much a novelty amongst the British public at the time, this represents an early usage of pigeons in a British military setting. In this blog post, we examine Captain Sir John Ross’s 1850-51 search for the Lost Franklin Bay Expedition and how pigeons were used on this venture.

On May 19, 1845, Royal Navy officer Captain Sir John Franklin sailed out of the river village Greenhithe toward the Canadian Arctic. Commanding the warships HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, his task was to explore the uncharted sections of the Northwest Passage, a sea lane in the Arctic Ocean linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Although Franklin didn’t know it at the time, it would be the last time he and his crew members saw England. Following a July 1845 sighting by a whaling ship, the Franklin Expedition vanished into the mists of time.

By the fall of 1846, Captain Sir John Ross, a Scottish Royal Navy officer, sensed that something bad had happened to his old friend. A seasoned polar explorer, Ross possessed considerable experience in Canada’s Arctic Archipelago, an area that encompasses the modern-day provinces of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories. In 1818, he sailed through this region on the first Admiralty-sponsored search for the Northwest Passage. Ross ultimately failed to uncover any useful information during that trip, but he redeemed himself on a return voyage in 1829, where he recorded valuable geographical and ethnological information, for which he received a knighthood from King William IV.

Drawing on his deep knowledge of the Arctic, Ross knew that Franklin should’ve returned at this point. He felt honor bound to do something—indeed, Ross had promised Franklin that he’d personally lead a relief party if Franklin failed to return within two years. With 1847 just a few months away, Ross contacted the Admiralty with an offer to lead a search-and-rescue mission the following summer. The Admiralty denied his request, and renewed its denial when Ross raised the issue again in 1847. But in April 1850, the Admiralty bowed to mounting public pressure and accepted Ross’s offer.

At 73 years of age, Ross now found himself preparing for the third Arctic voyage of his career. To assist the relief expedition, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC)—the company that essentially ran much of Canada at this time—offered a generous sum of £500. With this donation, Ross wasted no time in organizing the venture. With little time to spare, he quickly obtained two ships for the voyage: the Felix, a newly built schooner, and his personal yacht, the Mary, which would serve as a tender. He then assembled a crew and outlined the parameters of the journey. As planned, Ross would sail to the Lancaster Sound in Nunavut, where he’d join four other relief missions and coordinate search efforts for Franklin and his crew.

Before leaving the United Kingdom, Ross sought a way to maintain communications with the outside world. Letters could be sent to the Admiralty and HBC officials, but mail delivery was slow and not guaranteed. Outside of traditional mail service, an explorer was limited to sending written messages either via balloon or in bottles tossed into ocean currents. As a last-ditch effort, a message could be deposited in a cairn on some island for future explorers to find. If any of these methods failed, it could be months or even years before the British public learned of Ross’s (and ultimately Franklin’s) whereabouts.

Ross rose to the occasion and hatched a novel plan: he would attempt to deliver messages through carrier pigeons while searching for Franklin. To that end, he procured four homing pigeons—both an older and a younger pair—from a Ms. Dunlop, a fellow Scot living at Annan Hill, near Ayr. Ms. Dunlop’s pigeons had considerable experience in message delivery; she had trained them “to keep up a correspondence to two friends at a distance.” Ms. Dunlop evidently was an early practitioner of pigeon racing, as the sport was largely unknown amongst the British public at this time. Commercial firms, press agencies, and government institutions in the UK had relied on pigeons for message delivery since the late-18th century. With the invention of the electrical telegraph, however, these institutions quickly sold off their pigeon stocks to individual fanciers, leading to the growth of a nascent pigeon racing culture, especially amongst the professional classes. In its infancy in the 1850s, pigeon racing would soon flourish with the first homing pigeon clubs popping up by the 1870s.

On May 23rd, 1850, Ross and his vessels departed from Loch Ryan. With his pigeons in tow, Ross devised a plan for their use on his expedition: two pigeons would be freed when he made his winter quarters and two more would be released if and when he found Franklin. The relief mission reached the Lancaster Sound in August, where they connected with the other relief ships. For weeks, a total of ten ships scoured the barren landscape for signs of Franklin’s expedition. Ross apparently told his fellow rescuers about his plans to send messages via pigeon—they reacted with considerable amusement. “[M]any people laughed at the idea of a bird doing any service in such a cause,” Lieutenant Sherard Osborn, an officer aboard the relief ship HMS Pioneer, remarked in a post-expedition account. “I plead guilty, myself, to having joined in the laugh at the poor creatures, when, with feathers in a half-moulted state, I heard it proposed to despatch them.” Ross’s correspondence, however, reveals that he held the pigeons in high regard. “[W]hat I place the most faith in [are] four well-trained carrier pigeons,” he wrote in an August 13th letter sent to an HBC official. “I hope they will be the bearers of good news.” One can’t help but wonder why Ross believed in the pigeons so strongly; did he have personal experience with Britain’s burgeoning racing pigeon community?

By mid-September, the region’s waters had started freezing over, as the Arctic winter set in. Ross’s vessels and the other rescue ships settled in at Assistance Bay, located on the southern shore of Cornwallis Island. The Bay provided natural protection against the fierce northern winds, so the rescuers thought it appropriate to make their winter quarters at the site. In early October, Ross decided to release his pigeons. Per his contemporary diary, eleven messages from various officers were scribbled onto tiny pieces of paper and fastened to the pigeons. Modern pigeon fanciers may think it absurd that Ross expected the birds to fly all the way back to Scotland, but Ross, to his credit, seems to have known better. Indeed, per contemporary accounts, Ross intended for the pigeons to alight upon “some of the whaling vessels about the mouth of Hudson’s Straits” and “they would take a passage to England.”

Yet, initial attempts to release Ms. Dunlop’s pigeons failed miserably; the birds merely fluttered about the “boundless expanse of unbroken snow and ice” for a while, then returned to the Felix. Subsequent releases yielded the same exact outcome. Crew members tried firing guns at the birds to frighten them away, but the pigeons still refused to fly away from the ship. Having been confined for months aboard the ship, it appears the pigeons now viewed the Felix as their home loft.

Not willing to admit defeat, Ross and his crew rigged up a contraption that would’ve delighted Rube Goldberg. As they envisioned it, an 8 x 6 hydrogen balloon with an attached basket would carry the pigeons off the ship and over the Arctic landscape. After floating for 24 hours, a cord of slow match–a slow-burning cord used in black-powder weapons–connecting the basket to the balloon would burn up completely, causing the basket to spring open like a trapdoor, liberating the pigeons into the wild blue yonder. To keep the birds well fed, “a little split peas” would be placed in the basket for the birds to feast upon “before leaving their temporary abode on their aerial passage.”

Eyewitness accounts are muddled as to the specifics of the balloon launch. Dr. Peter Sutherland, a surgeon attached to the relief ships HMS Lady Franklin and HMS Sophia, reported that Ross “sent off two balloons, with a carrier pigeon attached to each in a small basket.” Lt. Osborn’s memoir, in contrast, only mentions “two birds duly freighted with intelligence and notes from the married men” secured to a single balloon. Meanwhile, an account appearing in the Ayr Observer exactly one year later claimed that Ross attached the younger pair of pigeons to a balloon, then did the same for the older pigeons. The newspaper’s account mirrors the Felix’s logbook, which records two separate pigeon releases occurring on the evenings of October 3rd and 4th, respectively.

What happened after the balloons floated away remains unclear as well. Per Ross’s personal diary, the pigeons “went rapidly out of sight S.S.E. true.” Yet the author of the Lady Franklin’s logbook recorded an entirely different result: “At 4”20 minits [sic] it fell in the water and drowned the pigeons [sic] about 3 miles distance from the ships.” This discrepancy perhaps can be reconciled by considering a post-expedition account appearing in the Ayr Observer. According to this version of events, the younger pigeons’ balloon “rose beautifully, and [was] seen careening along southward, till lost first to the eye and then to the telescope.” In contrast, “the older pair . . . were unfortunately drowned . . . when about two miles away” the balloon faltered and “trailed along the ice,” dipping periodically into “the snow and water.” Crew members chased after the balloon and tried to salvage the precious cargo, but “the birds could not be saved.”

Adding to the mystery, on October 22nd, the Glasgow Daily Mail claimed that Ross’s pigeons had been spotted on October 18th, attempting to visit Ms. Dunlop’s dovecote. This account alleged that two birds had “arrived within a short time of each other” and that neither of them had carried a despatch. The account alleged that one of the pigeons “was found to be considerably mutilated,” evidence apparently of an attached message having “been shot away.”

Within a week, the press had added various details to the initial story. Per this rapidly evolving narrative, a homing pigeon had been seen perched atop of Ms. Dunlop’s dovecote on October 13th. However, because the loft was undergoing repairs and had been sealed off, the pigeon (and possibly its mate) had flown away. On the 16th, Ms. Dunlop received information that “a strange carrier-pigeon had taken refuge at Shewalton, the seat of the Lord Justice General.” The pigeon was brought to Ms. Dunlop, “who at once recognised it as one of the young pair.” Upon being taken to its old loft, the pigeon purportedly “flew at once into the nest where it had been hatched,” even though there were upwards of forty similar compartments in the building. The newspapers claimed that the “feathers under the wing were very much ruffled, where it is customary to attach despatches,” but observed that “the note, if any were attached, has been lost.” If these accounts were to be trusted, then one or two of Ross’s pigeons had flown over 2000 miles from Cornwallis Island to Ayr.

Not everybody was convinced by these reports. On October 30th, a Stretford fancier named John Galloway expressed his skepticism in a letter to the Manchester Guardian. A stockbroker by profession, Galloway had been a pioneer of pigeon racing in the UK; as early as 1840, he had been training his loft to fly from London to Manchester in four hours. His birds, per an account written fifty years later, “were reckoned to be the best in England at that time and that they were bred from Antwerp birds imported by the stockbroker.” With his considerable expertise in the affairs of pigeon racing, Galloway could not stomach the inaccurate reporting surfacing in papers throughout the UK.

Writing off the newspaper accounts as “the clumsy invention of some wag,” Galloway proceeded to poke holes in the emerging tale. He observed that pigeons would not fly away from their home loft as Ross’s birds had allegedly done—”they would remain at their old habitation until nearly famished with hunger.” He then argued that the damaged feathers under the bird’s wing were irrelevant, as fanciers typically secured messages to the pigeon’s leg and “would just as soon think of tying a letter to a bird’s tail as under its wing.” Finally, Galloway attacked the distance traveled. “[N]o such distance as 2000 miles has been accomplished by any trained carrier pigeons,” he declared. He pointed to a 600-mile race between Spain and Belgium in 1844, where “[t]wo hundred trained pigeons, of the best breed in the world” were released “and only 70 returned.”

A particularly stinging critique appeared from none other than Ross’ colleague and fellow Royal Navy officer, Captain Charles Codrington Forsyth. Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane, had recruited Forsyth to lead a private expedition to the Arctic Archipelago. But after spending a mere 10 days in August hunting for Franklin, Forsyth had ordered his crew to head back to Scotland, reaching the UK by early October. Forsyth had personally seen Ross’s pigeons aboard the Felix. The Captain was not impressed by what he’d observed. While the press was still in a frenzy over the purported return of Ross’s bird(s), Forsyth expressed his doubts to the British literary magazine the Athenaeum. “[T]he birds are very young and not likely to stand the cold of the northern latitudes,” he reportedly told the periodical.

In spite of Galloway and others throwing cold water on the enterprise, much of the British public nonetheless remained convinced that future messages about Franklin would soon be arriving on the wings of a pigeon. On Nov. 2nd, residents of the Scottish city of Dundee allegedly spotted a pigeon “hovering about with a letter attached under one of the wings” near some ships along the River Tay. “Of course, there was no other conjecture but that it must have come from the Arctic regions with intelligence of Sir John Franklin, ” the Dundee Advertiser reported, “and the eagerness to get possession of the winged stranger was very great indeed.” The bird alighted onto a ship’s rigging, but flew away when people approached it. Later, it was reported to great dismay that the pigeon had simply traveled from nearby St Andrews.

Writing from the vantage point of 174 years later, it is difficult to make judgments. Nevertheless, a pigeon flying 2000 miles over snowy terrain and oceans in just under two weeks strains credulity. While modern-day, elite racing homers can fly 500 to 600 miles a day, in the mid-19th century, the breed was still in its infancy, especially in Britain. In 1842, for instance, pigeons liberated at Liverpool took nearly 12 hours to fly 300 miles to Brussels, Belgium. A similar race was held between Hull and Antwerp, Belgium in 1846. The fastest fliers made the trip of 280 to 300 miles in seven hours, while the remainder took upwards of a day. Notably, none of these racing pigeons were British natives, as evidenced by their homing to lofts in Belgium. At best, we can say that Ross released a pair of pigeons via balloon over the Arctic Archipelago in October 1850; everything afterwards must remain a matter of speculation.

Ross ultimately returned to the UK in late-September 1851 without any insight into Franklin’s fate. Despite media reports, his efforts to communicate by pigeons likely failed. Instead of tying his pigeons to balloons and hoping they’d land on a passing whaling ship, Ross would’ve been better served depositing the birds at an accessible HBC trading post and instructing the facility’s personnel in the finer points of flight training. If Ross had done this, the pigeons may have regarded the outpost as their home loft, setting them up to be distributed to the relief vessels. The ships, in turn, would’ve been able to remain in contact with the outpost as they searched for Franklin. Ross’s failure to attempt such a feat reveals the overall ignorance of homing pigeons’ flight abilities during this period. Still, the possibility that pigeons had returned from the Canadian Arctic excited a British public desperate for information about Franklin, especially Lady Franklin. In our next blog post, we’ll take a look at two more relief expeditions occurring in 1851 and 1852; inspired by Ross’s example, the individuals in charge of these missions brought pigeons with them for use in the Arctic.

Sources:

- “A Pigeon Race,” Manchester Weekly Times & Examiner, Jul. 25, 1846 at 3.

- “Arctic Searching Expedition,” The North British Review, Vol. X, No. 1, May 1851, at 255.

- “Carrier Pigeon,” The Glasgow Daily Mail, Nov. 6, 1850, at 4.

- “Carrier Pigeons,” The Zoologist, at 3709-10, Vol. 10, 1852 (citing Lieut. Sherard Osborn’s “Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal, at 174).

- “Despatch No. 2,” The Times, Oct. 1, 1850, at 8.

- Galloway, John, “The Reported Return of Sir John Ross’s Carrier Pigeon to Ayr,” The Guardian, Oct. 30, 1850 at 8.

- Johnes, Martin, “Pigeon Racing and Working-Class Culture in Britain, c. 1870-1950,” Cultural and Social History 4(3):361-383, September 2007.

- “Latest from Sir John Ross,” The Glasgow Daily Mail, Oct. 22, 1850, at 2.

- Old Hand, “The Racing Pigeons and Pigeon Racing for All – Vol. I” (1966).

- “Our Weekly Gossip,” The Athenaeum, No. 1201, Nov. 2, 1850.

- “Pigeon Race,” Sheffield and Rotherham Independent, Aug. 6, 1842, at 7.

- Ross, W. Gillies, Hunters on the Track: William Penny and the Search for Franklin (2019).

- “Sir John Ross and the Carrier Pigeons,” The Glasgow Herald, Oct. 3, 1851, at 6.

- “Sir John Ross’s Carrier-Pigeons,” The Leicestershire Mercury and General Advertiser for the Midland Counties, Oct. 25, 1851, at 4.

- “Sir John Ross’s Carrier Pigeons,” The Standard, Oct. 29, 1850, at 1.

- Sutherland, Peter, Journal of a Voyage in Baffin’s Bay and Barrow Straits, in the Years 1850-1851, Vol. 1, at 403 (1852).

- “The Carrier Pigeons of Sir John Ross,” The Observer, Oct. 28, 1850, at 7.

-

“Little Feathered Heroes”: Camp Pike’s Pigeon Service, 1917-1919

-

Pigeons in the Yugoslav Wars: The Croatian War of Independence (1991 A.D.)

In reading about military pigeons, one might be tempted to think that such services ended after the Second World War. For the most part, that’s accurate. Once electronic communication became cheaper and widespread in the post-war era, most militaries happily disbanded their pigeon services, eager to get rid of a seemingly archaic system. By the 1990s, only Switzerland’s Army boasted a fully fledged pigeon service and even that was phased out after voters slashed the military’s budget in 1994. Yet, unbelievably, pigeons were used to relay wartime messages as recently as 1991. This week, we take a look at how Serbian fighters in the Croatian War of Independence relied on pigeons to carry messages back home to loved ones.

In 1991, a series of geopolitical upheavals erupted across the globe. On January 17th, an international coalition led by the United States wrested Kuwait from Saddam Hussein’s control. Exactly five months later, lawmakers in South Africa repealed apartheid legislation, paving the way for a multi-racial government. And on Boxing Day, the Soviet Union officially dissolved after more than 70 years of rule.

Amidst this tumult, Yugoslavia—the great hope of South Slav nationalists in the aftermath of World War One—plunged into chaos. Composed of six constituent republics and two autonomous provinces divided roughly along ethnic lines, the nation saw a sharp rise in secessionist movements following the 1980 death of longtime President, Josip Broz Tito. On June 25th, 1991, the republics of Slovenia and Croatia declared independence. This inflamed tensions with the republic of Serbia, the largest and most dominant region in the country. Serbian officials sought to preserve the Yugoslav federal government, regarding the independence attempts as illegal and unconstitutional. Ostensibly to protect Serbs living in Croatia, the Serb-dominated Yugoslav People’s Army invaded the region on September 20th.

The Croatian War of Independence—just one in a series of conflicts known as the Yugoslav Wars—ushered in a level of brutality not seen in Europe since World War II. Indeed, one reporter characterized it as “a war fed by centuries-old hostilities and carried out with a crude vigor reminiscent of the Middle Ages.” Almost 20,000 people would die by war’s end, while devastating attacks on Croatian infrastructure caused nearly $37 billion in damages. Phone lines were quickly cut down, mail services interrupted, and transportation between different regions became nigh impossible. As a consequence, Serbian fighters venturing behind Croatian lines had no way of contacting friends and family. The soldiers’ complaints did not concern military officials, given that satellite technology allowed for them to stay in contact with Belgrade’s military HQ.

An unorthodox approach emerged in Požarevac, an eastern Serbian city. Famous for its swift carrier pigeons, the city hosted many fanciers, such as Slobodan Brkić, the president of the country’s premier pigeon society. A lover of pigeons since he was 6 years old, Brkić specialized in breeding Tipplers, a breed renowned for its flight stamina. In 1975, he founded the first Tippler club in Yugoslavia, while in the 1980s, he helped organize the Yugoslav Carrier Pigeon Association. Inspired by accounts of pigeons delivering despatches during the Great War, Brkić opted to donate his club’s birds to soldiers traveling along the route from Požarevac to Vukovar, Croatia, the site of fierce fighting.

Beginning in Mid-October, Brkić started distributing Požarevac’s pigeons to local soldiers. They were placed in “ventilated cake boxes” and driven into Croatia along with other supplies, a journey which required “days of stealthy movement.” Handlers on the frontline received the pigeons and distributed them to Požarevac fighters, who were instructed to secure brief messages to the birds’ leg bands and release them. In a testament to the birds’ prowess, they typically made the return journey in around 1 to 2 hours. The first pigeon to return—a bird called Whitehead—brought news home that one soldier was safe and fighting in the Croatian town of Mirkovci. By the end of November, at least 90 successful deliveries had been completed. Only one bird had been lost on the frontline, a racing pigeon named Big Red. His owner chalked the loss up to foul play; he claimed either a trained hawk or a Croatian sniper was likely responsible.

As the notes arrived, they were broadcast over the airwaves for the community’s benefit. “We began by reading the messages over local radio, because people here had no word on their boys at the front,” Brkić explained to an American journalist. The letters usually contained just a few words—”Dear father: I’m fine. Don’t worry about me. I’ll be home soon. Dule,” is a typical example. In spite of their brevity, the despatches brought intense joy to local families, who thanked Brkić profusely. “People were so happy to hear from their sons that they would come up to me on the street and kiss my hand.”

At the start of 1992, the intensity of the conflict waned. A cease-fire was brokered on January 2nd, thereby abrogating the need for pigeons. Based upon our research, we at Pigeons of War believe that this was the last conflict in which combatants depended upon pigeons to carry important messages. Požarevac’s pigeons, therefore, deserve much respect for proving that pigeon posts are still a viable option even in the Information Age.

Sources:

- “Слободан Бркић: Лет Дуг Читав Живот.” Recnaroda, 5 Sept. 2020, recnaroda.co.rs/slobodan-brkic-let-dug-citav-zivot/.

- Williams, Carol J., “Communications: Carrier Pigeons Make Comeback in War,” The Los Angeles Times, available at https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-01-11-mn-1529-story.html

-

The Finnish Defence Forces’ Pigeon Service: 1923 – 1940s A.D.

Finland emerged as a latecomer to the pigeon arms race—while other countries had started supplying their militaries with pigeons in the late-1800s, it wasn’t until the 1920s that Finland implemented its own military pigeon service. This late start is unsurprising, as Finland was a possession of the Russian Empire from 1809 to 1917, known formally as the Grand Duchy of Finland. As a Russian territory, Finland lacked a separate army of its own after 1901. In the wake of the Russian revolution, however, Finland declared its independence on December 6, 1917.

A punishing civil war erupted in Finland throughout the first half of 1918, during which the nation’s newly minted military experienced multiple communication system breakdowns. In the aftermath of the war, Finnish military leaders looked abroad for ideas to bolster the military’s communications. In 1923, Major Leo Ekberg spent time in Denmark, observing his host country’s telecommunications units. He eventually was assigned to the Danish Army’s signal corps and learned of its pigeon program, becoming intimately acquainted with training techniques. Just a few months later, in the spring of 1924, Lieutenant Colonel and erstwhile trapshooter Unio Sarlin put his training for the summer Olympics on hold and traveled to Morocco for a similar mission. He was surprised to find that the Moroccan Army relied on pigeons even though radio, telephone, and telegraph equipment was readily available.

With these experiences under their belts, the Finnish officers decided it was time for their military to develop its own pigeon service. The Army obtained a small flock of pigeons for experimental purposes in 1923. The flock remained limited to just a few birds and was used on a trial basis for the next several years. In October 1927, however, the Royal Danish Army shipped 40 pigeons to Finland’s military, free of cost. Suddenly, the Army found itself with a rapidly-growing pigeon service. Sarlin assumed the mantle of leadership over the fledgling Finnish Pigeon Service (FPS). When the Danish pigeons arrived in Finland, they were assigned to a telecommunications unit in Riihimäki, which was commanded by Major Ekberg.

Ekberg possessed the requisite experience to get the FPS off the ground and it showed. The unit’s breeding program swiftly exceeded expectations; indeed, in the opening months of 1928, the military found itself with a pigeon surplus. Too many, in fact, for the Army to properly house. Although the Army had been experimenting with pigeons since at least 1923, the primary loft could hold approximately hundred birds—and that was if they were crammed in there tightly. To improve the pigeon service, Army officials contacted the Ministry of Defense and requested funds for building a larger coop. They had low expectations—such a request had been made annually since 1924, yet the Ministry never prioritized the FPS’ needs.

While the army’s petition for a bigger pigeon loft languished in limbo, FPS officers looked for places to put their birds in the interim. The White Guard, the country’s voluntary militia, expressed an interest in keeping some of the pigeons at its officers’ school in Tuulusa, while Ekberg thought that they might be useful at sites in eastern Finland, or in areas between the mainland and the outer islands to enhance coastal defense communications. The Ministry, nonetheless, ignored these proposals. Fed up with the agency’s intransigence, Ekberg told the Ministry bluntly that if it refused to build a larger coop for the military’s pigeons by 1930, then the pigeon service should be terminated, since no real support had been provided since its founding in 1923.

Ekberg’s tough tone with the Ministry worked—it quickly agreed to provide the FPS with more support. Over the next several years, the Ministry would work closely with Sarlin and Ekberg to develop a sophisticated military pigeon service. With the Ministry’s full support, the FPS once again looked abroad for inspiration. In 1930, the FPS received detailed information from their French counterparts about the French Army’s pigeon service. In 1931, FPS officials toured Germany’s pigeon stations for several weeks. The officials were awestruck at the amount of pigeon merely at the German Army’s central loft in Spandau, 1200. Encouraged by these trips, Sarlin planned further fact-finding missions to Sweden, Norway, and Estonia.

Armed with knowledge gleaned from some of the world’s preeminent military pigeon services, the FPS embarked on a series of projects. Permanent lofts were planned for military installations in Helsinki, Parola, Pori, Turku, Kangasa, Hämeenlinna, and Vyborg. FPS officials also wanted to develop improved training courses, import quality stock from Germany, and mobile lofts for use out in the field. It’s unclear from the record how many of these objectives were met.

Meanwhile, the army’s pigeon service expanded to other branches of Finland’s military. In August 1933, the Air Force received a pigeon station at the Suur-Merijoki airbase near Vyborg. The birds were to be used by pilots to communicate with the ground in lieu of radio, which still was not feasible for Finnish aircraft. That same year, the Navy received a batch of pigeons at its Maritime Defense headquarters in Helsinki. Naval officials wanted the birds for a special project: maintaining communication from submarines out at sea. Normally, a submarine could release pigeons upon surfacing, but such an option was not available to downed subs or when it was not safe to surface. To bring the pigeons from the sub to the surface, a torpedo was designed to be large enough for two military pigeons to fit inside. Ideally, upon being launched from the sub, the torpedo would rise to the surface and open up, allowing the pigeons to fly messages to the nearest naval facility. While this may seem a bit of a harebrained scheme to modern audiences, tests had demonstrated the torpedo was a safe and secure option for pigeons. Sarlin approved of these experiments, but it doesn’t appear the pigeon torpedo ever made it out of the experimental stage.

By 1935, the Finish military boasted 690 pigeons housed in lofts in Helsinki, Valkjärvi, Kiviniemi and Suur-Merijoki. These pigeons included both foreign strains and those supplied by a Finnish fancier group. As with other services, an issue frequently encountered was hawk and falcon attacks. In the fall of 1933, for example, peregrine falcons swooped in during a naval training session and killed half of the birds present. Avian tuberculosis was also a major threat, plaguing the military’s lofts. At the Kiviniemi loft, around 60 pigeons of Latvian stock were found to have tuberculosis. Other common diseases included proctitis, E. Coli, infectious rhinitis, and thrush. Finally, Finland’s extreme subarctic climate occasionally affected the birds’ performance.

In spite of the FPS’s best efforts, Finland’s military pigeon service began to lose steam in the mid-1930s, as improvements in radio technology pushed the pigeons to margins. In 1938, an internal assessment of the military’s communication sectors mentioned pigeons very little in comparison to radio units. The author recommended that the pigeons be given to the Army’s signal corps, from which they could be transported quickly to the front line by motor vehicles if necessary. Yet, when the Winter War started a year later, the birds were not incorporated into combat operations; an oversupply of Estonian field radios meant that the pigeons were no longer vital to the military’s interests. Near the end of World War II, the government slaughtered the birds and distributed the meat to injured soldiers in military hospitals. That was the death knell for the FPS—the Finnish military never worked with pigeons again.

In spite of its short existence and ignominious end, the FPS has managed to leave a footprint. The public can view exhibits dedicated to the FPS at the National Message Museum in Riihimäki and the Finnish Air Force Museum in Tikkakoski. The FPS has even inspired a modern work of fiction. Heli-Maija Heikkinen, a history lecturer and long-time admirer of the FPS, was dismayed that no stories of brave war pigeons had been preserved in the Finnish military archives. To remedy this, she wrote a novel in 2014, entitled Viestikyyhkyupseeri (The Carrier Pigeon Officer). Set during World War II, the book concerns Frans Jokimies, a pigeon trainer, breeder, and caretaker employed by the Finnish military. In September 1944, Frans receives an order from his superiors to slaughter the military’s birds. He cannot follow this unconscionable decree, so he and his wife Anja flee to Denmark with the pigeons in tow and remain there for decades. Amidst this backdrop, the author explores themes of war and sacrifice, forgiveness and relationships. It’s a worthy tribute to the FPS’ officers and pigeons and proof of their lasting legacy.

Sources:

- Karjalainen, Mikko, “Viestikyyhkyjä taivaalla,” Puolustusvoimien Kokeilutoiminta Vuosina 1918-1939, Vol. 1: 43, 2021, at 166, available at https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/180859/PVn_kokeilutoiminta_Karjalainen%20et%20al.%20%28verkko%29.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- “Viestikyyhkyt Olivat Sota-Ajan Unohdettuja Sankareita.” Yle Uutiset, 27 Nov. 2014, yle.fi/a/3-7654835.

- Viestikyyhkyupseeri – Heli-Maija Heikkinen , kirja.elisa.fi/ekirja/viestikyyhkyupseeri.

- “Viestimuseo Muistaa Vainovalkeat Ja Kirjekyyhkyt.” Hämeen Sanomat, 14 June 2018, http://www.hameensanomat.fi/paikalliset/5147126.

-

“Very Gallant Gentlemen:” The Pigeons of the Royal Naval Air Service, 1916-1918 A.D.

The United Kingdom’s Royal Air Force (RAF) enjoys the honor of being the world’s first independent air force. For over 100 years, the RAF has protected Britain’s skies and air space from harm, playing a major role in the Second World War and the Cold War. Few people, however, are aware of the RAF’s predecessors during the First World War, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) and the Royal Flying Corps, which merged in 1918. This week, we take a look at the RNAS and how it relied on pigeons during the Great War.

On July 1st, 1914, the Admiralty of the United Kingdom officially created the RNAS. Envisioned as the Royal Navy’s (RN) analogue to the Army’s Royal Flying Corps, the RNAS had three primary objectives: maritime reconnaissance, patrolling for enemy ships and U-boats, and attacking enemy coastal territory. The newly formed unit assumed ownership over “[a]ll seaplanes, aeroplanes, airships, seaplane ships, balloons, kites, and any other type of aircraft that may from time to time be employed for naval purposes.” All naval personnel with aircraft experience, both active and reserve, were immediately reassigned to the RNAS. Within just a few weeks, the RNAS boasted 93 aircraft, six airships, two balloons, and 727 officers and enlisted men.

Barely a month after its launch, the RNAS found itself preparing to take part in the largest European engagement since the days of Napoleon. After several weeks of fighting, an opportunity emerged for the RNAS to test its reconnaissance and offensive capabilities. Military officials wanted to bombard the Imperial German Navy’s airship bases on the Heligoland Bight, a bay within the North Sea, to prevent future zeppelin attacks on the British mainland. But the bases were out of range for British-based aircraft, so a crew from the RNAS was recruited to aerially reconnoiter the Heligoland Bight and bomb any zeppelin sheds spotted in the vicinity. On Christmas morning 1914, seven RNAS seaplanes took off from a group of seaplane tenders stationed near the bay. The seaplanes flew for over three hours, surveying the area and bombing a few minor shore installations. Although the results obtained by the RNAS were meager, the Raid on Cuxhaven—as it came to be known—demonstrated the potential of a unified sea-and-air attack.

The RNAS also spent considerable time patrolling for enemy U-boats, which were sinking thousands of merchant ships bound for French and British ports. Over the course of the war, the RNAS searched over 4,000 square miles in the North Sea, the English Channel, and along the coast of Gibraltar for submarines. Although the seaplanes’ guns generally weren’t sufficient to sink submarines—only one German U-boat was sunk by a British plane unassisted by warships during the conflict—the pilots could relay the subs’ locations to the RN’s surface fleet.

An issue frequently encountered in the RNAS was how to communicate with pilots who were stranded in the sea. Seaplanes and flying boats were too small to accommodate a wireless set until 1917. Even after the planes received wireless units, the devices were useless in the event of engine failure. As readers of this blog will recognize, this is the exact emergency scenario for which a pigeon service is ideal. But the RN had phased out its pigeons in 1908, viewing the birds as antiquated with the rise of wireless telegraphy. RNAS officials were inspired to reinstitute a naval pigeon service following an episode involving their French counterparts. On June 8th, 1916, an injured pigeon arrived at Saint-Pol-sur-Mer bearing a message from a downed seaplane near Ostend and Zeebrugge along the Belgian coast. A French destroyer traveled to the crash site, only to encounter a German torpedo boat attempting to haul the seaplane away. A skirmish broke out and the seaplane was ultimately lost.

Even though the French had failed to recover the seaplane, a British RNAS station in Dunkirk learned of this episode and was impressed with its results. An inquiry led to the donation of a few well-trained birds, which were rapidly put to use. Just two days later, two RNAS seaplanes flying 4,000 feet over Zeebrugge released pigeons with accompanying despatches revealing the area was enemy free. The pigeons successfully returned to their Dunkirk lofts bearing good tidings. On June 20th and 24th, pigeons brought news to Dunkirk of shot-down RNAS seaplanes, facilitating their rescues.

With such an auspicious start, it soon became standard operating procedure for each RNAS flight crew to carry a basket of pigeons with them on every journey. Writing nearly 90 years later, Henry Allingham—the last surviving veteran of the RNAS—explained the process:

[W]e didn’t have radio. We had pigeons which we carried in a basket. . . . Some of our people who were adrift in the drink could be there for up to five days, and they used to let the pigeons go. They would fly back to the loft at the station, and a search party would be sent out to look for them. As a general rule, after five days of searching, they’d give up and the men were lost.

RNAS pilots and observers received specialized training from pigeon experts before they ever handled a bird. It was especially important that they be instructed on how to avoid harming pigeons during aerial releases. “The liberation of a pigeon from a seaplane in flight requires a certain amount of dexterity,” remarked one contemporary publication, “as the bird is liable to be caught in the slip-stream of the airscrew and dashed against the tail group.”

The RNAS maintained flocks of pigeons at the principal naval air stations on the mainland. Although the RNAS owned some 1,000 birds outright, it also received three thousand birds from donors as diverse as King George V. When released at sea, the donated pigeons flew back to the original owners home, where the owner would telegraph the message’s contents to the proper authorities. The bird would eventually be returned to the nearest RNAS station and reunited with its crew. Until then, the owner was expected to feed and care for the bird without compensation from the RNAS.

The RNAS’s pigeon program was wildly successful. In spring 1918, it was claimed that RNAS pigeons had carried over 1500 messages. Newspaper accounts regaled audiences with tales of pigeons saving RNAS servicemembers from watery graves. In one widely reported story, a seaplane pilot, forced to make an emergency landing off the coast of Kent, released a pigeon at 7:24 a.m. The bird returned to its loft by 8:00 a.m. and a trawler was enroute within 30 minutes to rescue the pilot. An even more impressive feat occurred when four pigeons arrived at a station one after the other, telling the story of a fierce dogfight over the North Sea fragment-by-fragment. However, sometimes the news brought back via pigeon wasn’t pleasant. Once, a pigeon returned with a message written in German declaring that the RNAS pilot and seaplane had been captured.

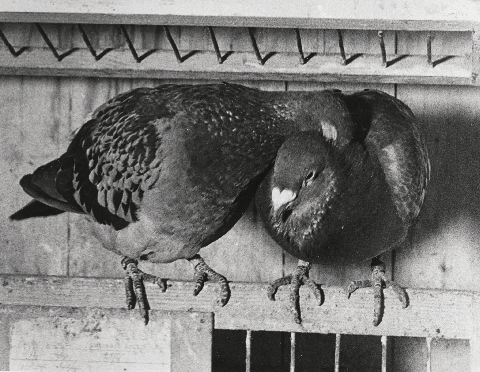

The most famous story of a rescue by an RNAS pigeon occurred on September 5th, 1917. That morning, two RNAS planes flew out of the Yarmouth naval air station, heading toward the North Sea. They were in search of German zeppelins, which had been operating near Terschelling Island, north of the Netherlands. A total of six men were present: four in a seaplane and two in a biplane. Halfway into the flight, they spotted two zeppelins and opened fire. The dirigibles attained the upper-hand, riddling the English planes with bullets, while German ships fired anti-aircraft shells from below. As the Germans left the scene, the biplane plummeted into the ocean, its engine destroyed. The seaplane was still airborne, though it suffered from a broken wing and a misfiring engine. It landed near the biplane and its crew brought the two men aboard. Although the six men were unharmed, the seaplane failed to become airborne after repeated attempts. They opted to release four pigeons over three days with news of their calamity. Only one pigeon managed to make the 50-mile flight back to the Norfolk coast, Pigeon N.U.R.P/17/F.16331, but it died immediately from exhaustion. Reading its message, naval officials learned of the men’s location and rescued them; not a single life had been lost thanks to the pigeon’s sacrifice.

At its peak, the RNAS comprised 55,066 personnel, 2,949 aircraft, 103 airships and 126 coastal stations. Yet, by 1918, British war planners were keen to consolidate the nation’s military aircraft and personnel under one branch. On April 1, 1918, the RNAS merged with the Royal Flying Corps to become the RAF. The contributions of the RNAS’ birds weren’t forgotten, however. In November 1918, 13 former RNAS birds were displayed at a London event; between all of them, they had saved a dozen lives and many downed aircrafts. In April 1919, the RAF issued an official list of pigeons who had distinguished themselves in wartime service on flying boat and seaplane operations. Meanwhile, Pigeon N.U.R.P/17/F.16331 was preserved in a glass case bearing the inscription, “A Very Gallant Gentleman;” it can still be seen to this day at the UK’s RAF Museum.

Sources:

- Flying Boats over the North Sea.” RAF Museum, 1 Feb. 2021, https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/blog/flying-boats-over-the-north-sea/;

- Milford, Humphrey, The Periodical, Vol. 13, No. 145, June 15, 1928, at 75.

- O’Flaherty, Patrick, “Peaceful Pigeons in Modern Warfare,” The Montreal Star, Mar. 2, 1918, at 17.

- “Pigeons Bring Help to Our Fighting Men,” The Buffalo News, Sep. 26, 1919, at 19.

- “R.A.F. Pigeon Service,” The Aeroplane, Vol. 16, No. 2, Jan. 15, 1919, at 306.

- “Royal Naval Air Service,” Flight, Vol. 6, No. 26, June 26, 1914, at 686-89.

- Simkin, John. Royal Naval Air Service. Spartacus Educational, https://spartacus-educational.com/FWWrnas.htm.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence, The Great War at Sea, at 264 (2014).

- “The Gallant Pigeon That Saved Six WW1 Airmen Lost in the North Sea.” Look and Learn, 30 May 2012, https://www.lookandlearn.com/blog/18494/the-gallant-pigeon-that-.

- “Wireless Signals,” The Nottingham Evening Post, Feb. 4, 1908, at 3.

- “WW1 Flying Boat Crew.” RAF Museum, 1 Feb. 2021, https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/blog/ww1-flying-boat-crew/.

-

The Martyrs of Nomain: A Tale of Pigeons and Spycraft During the Great War

For all practical purposes, the Great War began when Germany invaded Belgium on August 4th, 1914. Despite the valiant efforts of the Belgian Army, it was an unfair fight and the small country was quickly overrun. For the duration of the war, German military authorities occupied nearly the entire territory. This is common knowledge, yet many popular histories of the conflict neglect the German occupation of northeast France during this period. Indeed, by November, Germany had gained a foothold in ten French departments, the most populous of which was the Nord Department. This week, we take a look at four brave residents of the Nord who were executed for engaging in clandestine pigeon networks.

At the close of 1914, over 1 million French residents in the Nord Department found themselves under German occupation. Naturally, the presence of a foreign army in their homeland triggered active resistance movements, as in Belgium and Luxembourg. Espionage emerged as a powerful form of undermining German authority; Nordistes were all too eager to provide Allied secret services with enemy intelligence. While men and women bravely volunteered their services and passed on info to secret agents in person, others opted to use pigeons to send clandestine information back to the Allies. This is unsurprising—pigeon keeping was a popular pastime in the Nord region, with over 20,000 members enrolled in a regional club.

But pigeons were in short supply throughout the Nord; the German military government had ordered their destruction in October 1914 to prevent communication with the Allies. To provide Nordistes with much-needed pigeons, in March 1917, British intelligence started airdropping pigeons via balloon or plane into occupied France. Attached to a parachute, the pigeon floated down into a meadow or field, waiting for a Nordiste to find it. In the event someone found the bird, they’d notice a detailed questionnaire attached to the its leg. It was hoped that patriotic individuals would look over the questionnaire and reveal important details about German military units and movements. A set of instructions cautioned participants to disguise their handwriting and not to include their real names or addresses in case Germans intercepted the bird. This was a necessary measure, in light of French patriotism. “[T]he French people are fond of glory,” a French partisan warned a British intelligence official, “and unless they are warned, I am afraid some of them will be sticking their names to the bottom of the message just to show how they are trying to help their country.”

Getting the pigeon behind enemy lines was the simple part. Nordistes took a huge risk if they decided to use the airdropped bird for espionage. Those who had a pigeon in their possession had to be extra cautious that no one actually saw the bird. “Keeping them . . . without arousing the suspicion of the Germans or the curiosity of inquisitive neighbors, proved too great a difficulty,” British intelligence officer Henry Landau reflected in a post-war memoir of his espionage activities. If a person did send vital information, Germans might intercept the pigeon and discover his or her identity. Finally, sometimes the Germans themselves planted one of their own pigeons for unsuspecting Nordistes to find. Any info sent by that bird would end up in German lofts.

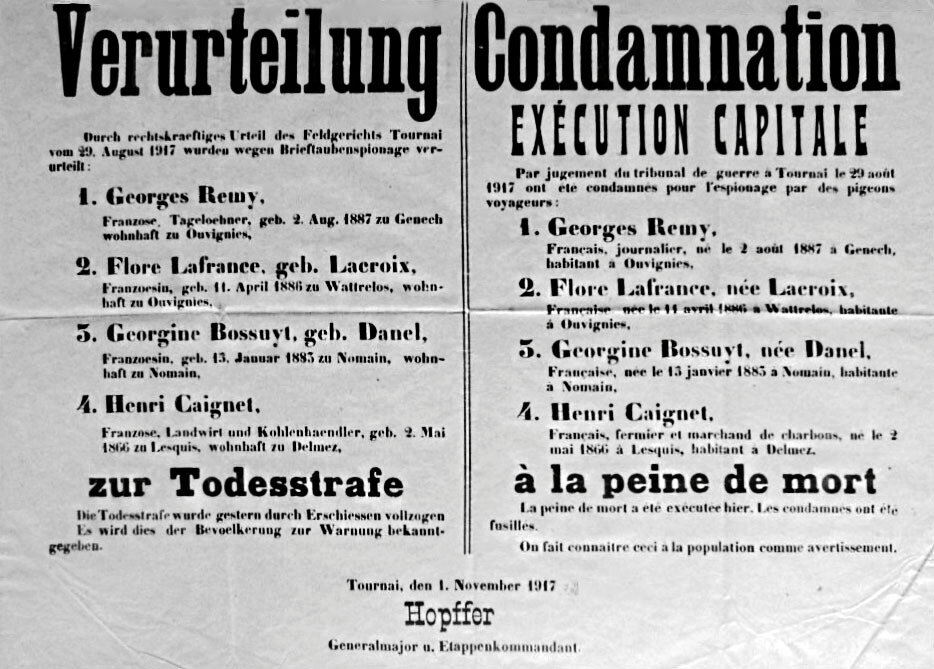

Still, those bold enough to try this venture occasionally passed on intelligence of real value to Allied officials. In May 1917, for instance, several individuals sent via pigeon the location of several ammunition depots and three big enemy guns in Cambrais. A few days later, French planes bombed the depots and two of the big guns. For this reason, German military authorities took a draconian stance against the use of pigeons for espionage. Anyone found in possession of a pigeon or identified in an intercepted despatch faced immediate arrest, followed by a trial before military tribunals. In the event of a conviction, execution by firing squad was the usual penalty.

It is in this milieu that we encounter the subjects of our story. In April 1917, a German soldier stationed in Lens, Belgium shoots down a pigeon in flight. He quickly discovers it’s a spy pigeon when he sees a filled-out questionnaire attached to its leg. In looking over the questionnaire, he realizes that an active spy ring exists in Nomain, a town in the Nord. Three names appear in the document, all residents of Nomain: Georges Rémy, a railway worker, Henri Caignet, a coal merchant, and Flore LaFrance, a young mother. The German authorities swiftly arrest these individuals and their spouses and transport them to Tournai, Belgium. An investigation into the matter implicates several other collaborators, including Georgine Bossuyt; like LaFrance, she, too, is a mother of young children.

On August 4th, the accused appear before a war tribunal in Antwerp. Following the hearings, the tribunal sentences Rémy, Caignet, LaFrance, and Bossuyt to death; their spouses and other collaborators receive decade-long prison terms instead. Although the condemned file appeals of their sentences, their petition is denied in September. They’re sent back to the Tournai Citadel to await execution by firing squad. They don’t know when it will happen. In the meantime, Rémy’s wife gives birth to a daughter; she names her Georgette.

On October 31st, the collaborators are informed at 11:00 am that they will be shot at 5:00 pm. They are granted just two hours to gather with their families in a makeshift chapel and say goodbye. Eyewitness accounts paint a heart wrenching picture of these last moments. LaFrance cradles Rémy’s newborn daughter as he embraces his wife. Caignet kisses his daughter Yvonne, letting her know that he is to be shot that evening. Bossuyt bids her husband farewell, but is not allowed to see her children—they are too young and left with some of the Citadel’s nuns. An hour before the sentence is to be carried out, the families depart. A final mass for the condemned is held where they receive communion.

As five o’clock draws near, the condemned are brought to the execution site. Rémy’s legs give out and he is dragged along by two burly soldiers. Meanwhile, the women put on a brave show. Bossuyt and LaFrance—sporting cockades emblazoned with France’s national colors—vigorously refuse to be blindfolded. Each prisoner is tied to a post. The women shout “Vive La France!” for their final words. As the soldiers prepare to fire, one refuses to shoot. He is quickly replaced and the firing commences. The women are shot first and their bodies placed in coffins, but it is immediately apparent to all that Bossuyt is still breathing. She is pulled halfway out of the coffin and shot again. A priest breaks down in tears as he blesses the women’s bodies. The men are shot next without incident. The bodies are buried onsite in a mass grave before nightfall.

German authorities are confident these executions will serve as a deterrent. But they’re wrong. In spite of German threats, collaborators continue using pigeons to communicate with the Allies throughout 1917 and 1918. By war’s end, nearly 40% of the questionnaires provided by the British have returned via pigeon, beating internal estimates that only 5% would return.

The story of Nomain’s martyrs received much attention in the years following the war. Two monuments were publicly dedicated to them during the Interwar period: the Monument aux Morts in Nomain and the Monument de la caserne Ruquoy in Tournai. In the 1920s, the French government posthumously awarded each individual the Legion d’honneur, the country’s highest order of merit. Even 100 years later, their story occasionally surfaces in French and Belgian media.

This grim chapter reminds us of the harsh realities of war. In using pigeons to send confidential information to the Allies, the martyrs of Nomain took major risks and it cost them dearly—not only did they lose their lives, their children grew up without them. And yet they took these chances, motivated by a love for France that transcended self. We at Pigeons of War salute these courageous individuals for making the ultimate sacrifice to aid the Allied cause.

Sources

- Bausiers, Christian. “Les Patriotes Fusillés, Héros Méconnus.” Skyrock, 9 Feb. 2013, https://edidep.skyrock.com/3142180984-CONNAITRE-TOURNAI-SON-HISTOIRE-SES-REALISATIONS-SES-PROJETS.html.

- Connolly, James E., The Experience of Occupation in the Nord, 1914-18, at 8, 12, 15, 266-69 (2018).

- Département: 59 – Nord, https://www.memorialgenweb.org/memorial3/html/fr/resultcommune.php?idsource=30202&dpt=59

- Landau, Henry, All’s Fair: The Story of the British Secret Service Behind the German Lines, at 81 (1934).

- Thuliez, Louise, Condemned to Death, at 45-46 (1934)

-

The Kingdom of Serbia’s Pigeon Stations: 1908 – 1918 A.D.

The Balkan Peninsula was a hotbed of activity during the latter-half of the 19th century. The Ottoman Empire had ruled the region for centuries, but a rise in ethnic nationalism challenged the status quo. Following a series of wars and rebellions, the Sick Man of Europe gradually receded from the Peninsula. At the close of the century, three newly independent countries existed in the Balkans: The Kingdom of Serbia; the Principality of Montenegro; and the Kingdom of Romania. This week, we take a look at the Kingdom of Serbia and its military pigeon service.

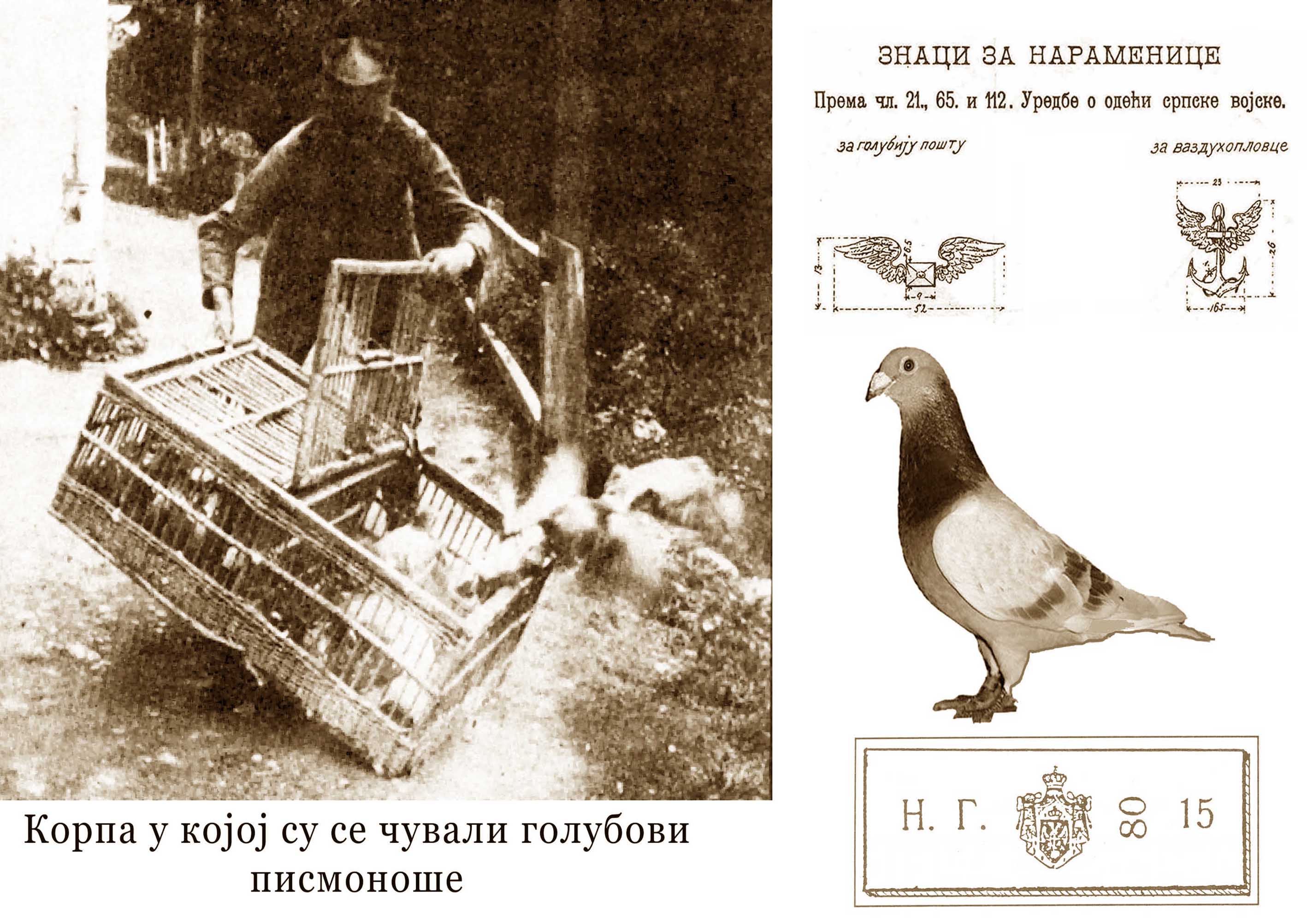

The Kingdom of Serbia implemented a military pigeon service in the opening years of the 20th century. The service was the brainchild of Kosta Miletić, an innovator of military aviation and the first Serbian Air Force Commander. As a young army officer, Miletić had been sent to a Russian military aviation school in 1901. At that time, military aircraft were limited primarily to gas-filled observation balloons, which had been deployed in the American Civil War and Franco-Prussian War to great effect. Throughout 1901 and 1902, Miletić studied up on the art of military ballooning, achieving excellent grades. He also spent six months at the school’s pigeon station, where he learned that the birds could be used by balloon pilots to send status reports to troops on the ground. In September 1902, Miletić had the opportunity of putting his ballooning and pigeon training in action. The Russian Army had planned a series of grand maneuvers across the country and Miletić was assigned to the Kiev Army. Piloting a balloon, he attained a height of 1100 meters and a distance of 180 kilometers, all the while sending messages back to the ground via pigeon.

Miletić returned to Serbia as the country’s first aeronaut The Minister of Defense assigned him to work in the Ministry’s engineering department, where he developed plans for balloon units in the Army. Inspired by Russia’s pigeon stations, he also sketched out concepts for a network of pigeon stations across Serbia. However, when Miletić presented his ideas to the Minister, the plans were shelved and Miletić reassigned to a different division.