At Pigeons of War, we’ve devoted several articles to famous war pigeons. We’ve written about Gustav and President Wilson, for instance, both of whom spent their formative years in the military. However, thousands of pigeons from all walks of life were donated to the military during both World Wars. This week, we take a look at a newspaper pigeon’s accomplishments before he was drafted for service in World War II.

In the 1930s, photojournalism—the process of telling news stories through images—emerged as a popular trend in the print media world. Eager to meet their audiences’ appetites, newspapers looked for ways to get pictures from their photographers as quickly as possible for immediate circulation. Portable wirephoto equipment, which would allow for the instantaneous transmission of pictures over phone lines, was bulky and impracticable at this point. Meanwhile, in highly urbanized metro areas, cars, bicycles, and human couriers faced the obstacle of traffic congestion. A delay of even just a few minutes might result in a rival paper printing photos from the same news story.

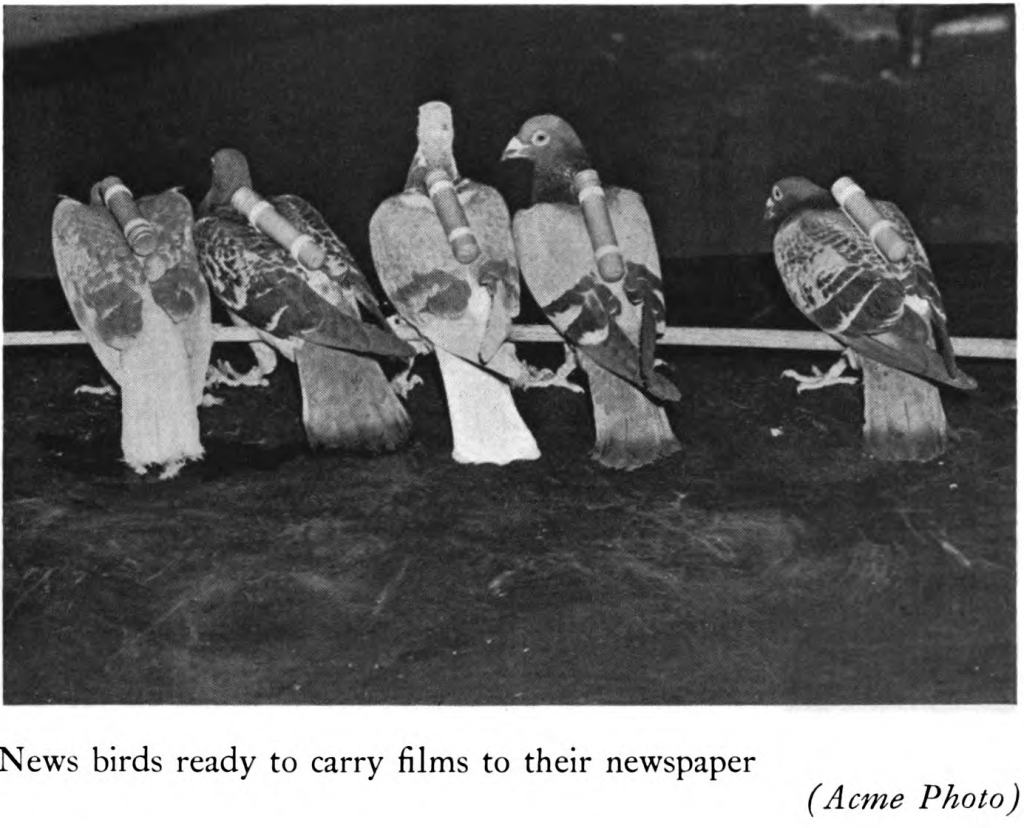

For these reasons, several New York-based newspapers and photographic agencies actively maintained flocks of pigeons throughout the decade. These birds—cross-breeds of Army pigeons from Fort Monmouth, New Jersey (NJ) and prize-winning racing homers—transported photographic negatives from photojournalists out in the field to the newspapers’ offices. The pigeons regularly accompanied reporters assigned to ship arrivals, murder cases, sports games, natural disasters, and run-of-the-mill news stories. Most of these assignments were within 30 or 40 miles of the newspapers’ lofts, but could extend to over 100 miles away, depending upon the needs of the story.

A standard operating procedure existed for ensuring proper transmission of the negatives to the newsroom. After taking a picture, the photojournalist would put their camera in a black bag and remove the film so it wouldn’t be damaged by the light. Next, the negative and a caption for the picture, written on thin onion skin paper, would be inserted into a capsule and fastened either to the pigeon’s leg or its back via a chest harness. The pigeon then would be released, flying back to the roof of the newspaper’s offices within a few minutes. The negative would be rushed to a darkroom, where it would be developed into a photographic print fit for circulation.

In a remarkable illustration of the efficiency of this process, a newspaper pigeon flew from an ocean liner bearing a negative of the ex-mayor of New York City, Jimmy Walker, who had been hiding out in Europe since he resigned in disgrace several years earlier. By the time Walker departed the ship, the photo had been developed and printed in the paper’s latest edition. Much to the delight of the paper’s pigeon manager, a photographer snapped a picture of Walker buying a copy.

Into this milieu was born Braddock, a grey-checkered cock. He was likely named for the then-reigning heavyweight champion James J. Braddock rather than the ill-fated general of the French-and-Indian War. Braddock worked for the Newspaper Enterprise Association (NEA) Service, Inc., a newspaper syndication service that supplied photographs to its client papers. In 1935, Robert J. Ronchon, the commercial manager for the syndicate, had installed a massive pigeon loft on top of the 363-foot skyscraper where NEA’s New York office was located. Weighing 10,000 pounds and measuring 27 feet long by 6 feet wide, the loft was declared by Sergeant Clifford Poutre of the US Army Signal Corps to be “the most scientifically built house for racing pigeons” in existence. It was subdivided into 4 coops, each of which was capable of housing 75 birds, and a small office for an attendant to lounge in while awaiting incoming despatches.

After several years of carrying photos to NEA’s rooftop loft, Braddock was recruited for a special mission in the spring of 1939. A 10-year-old girl named Margaret Gillen had recently been admitted to a New York hospital for several operations. While she recuperated, a sheet of goldfinch stamps issued by the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) caught her fancy. Margaret decided right then and there that she wanted a pet goldfinch of her own—it could sing to her while she was in the hospital. She wrote to the president of the NWF, who happened to be famed cartoonist J. N. “Ding” Darling, asking if he could get her one. Darling saw an opportunity to make a little girl happy and promote the upcoming National Wildlife Week. He wrote back to Margaret, telling her that he couldn’t get her a wild songbird, but would do the next best thing.

Darling bought a white, roller canary from a petshop in Union City, New Jersey. To get it to Margaret, he reached out to Ronchon, inquiring whether it was possible for one of NEA’s pigeons to deliver the canary to New York. Ronchon, accepting the challenge, selected Braddock for the task. A special, 5-inch aluminum tube was designed by Ronchon for the canary—it featured four tiny stabilizers, rounded ends, and a spinning nose that could draw in cool air for the passenger’s comfort. When loaded up with a canary, the tube weighed the same as a 3-cent letter.

The tube was secured to Braddock’s back through a chest harness. A few test flights occurred involving a different canary named “Tessie Testpilot.” These proved to be a success. “On several flights,” reported an NEA correspondent, “Miss Testpilot came through without a single ruffled feather and feeling chipper enough on ‘stepping down the gangplank’ to chirp a bit.”

Finally, it was time for Braddock to deliver Margaret’s canary. He was released from Elizabeth, NJ and flew towards New York City. A stiff wind impeded his progress, but after 42 minutes, he landed on NEA’s rooftop with the canary in tip-top shape. A team of journalists escorted the canary to Margaret. A flurry of photographs taken that day show Margaret’s genuine joy in receiving her new pet. In a token of her appreciation, she named the bird Darling.

Braddock’s canary caper was the biggest moment of his career with NEA. He soon returned to the daily grind of news reporting. With the US’s entry into World War II, however, Army officials fretted that the Signal Corps’ peacetime supply of pigeons would not be enough for wartime. They appealed to fanciers to donate their bids. Evidently, NEA felt the call of duty—at some point in 1942 or 1943 (the date is not certain), Braddock and 99 of his peers were shipped to Fort Monmouth. No further information can be found about his wartime service. Given his advanced age, Braddock was probably used for breeding purposes. Thanks to the work of pigeons like Braddock, the Signal Corps had more than enough birds by early 1944.

Even though Braddock may not have had an illustrious military record like Cher Ami or the Mocker, he gave up his career when his country came calling. For that, we salute him.

Sources:

- Brown, Wilfred, “Trained Birds Deliver Messages Faithfully in War and Peace,” The Daily Advertiser, Jan. 20, 1940, at 5.

- Cothren, Marion, Pigeon Heroes: Birds of War and Messengers of Peace, 36-39, (1944).

- Lower, Elmer, “Pigeon Carries Canary on First ‘Piggy-Back’ Flight,” The Chickasha Daily, Mar. 23, 1939, at 4.

- Misurell, Edwin, “The Army Hatches a New Class of Recruits,” The Salt Lake Tribune, Nov. 27, 1938, at 73.

- Jones, Robert W., Journalism in the United States, at 554 (1947).

- Ross, Paul, “Swift, Feathered Couriers Start NEA Newspictures on Way to Olympian,” The Olympian, Oct. 30, 1938, at 11.

2 responses to “Braddock: The Newspaper Pigeon Who Joined The Army”

This is an amazing story! Here’s to you, Braddock

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading! Braddock was an amazing pigeon!

LikeLike