Pigeons and birds of prey have had a troubled relationship since the beginning. As nations rushed to set up military pigeon services in the 19th century, officials devoted ample resources to preventing bird-on-bird attacks. This was a serious concern for militaries. Hawks, falcons, and even owls could quickly annihilate an entire flock of pigeons during a training flight. In wartime, an enemy force could train falcons to intercept military pigeons. Aware of these issues, the United States Army waged war against raptors for decades.

The US Army’s initial efforts at keeping pigeons were sabotaged by a marauding hawk. In 1878-79, Colonel Nelson Miles requested a dozen homing pigeons from the Signal Corps for use on the Great Plains. As commander of the 5th Infantry, Col. Miles possessed a keen interest in maintaining communications amongst his troops while they were out in the field. Having achieved success with the heliograph—a semaphore system that signals by flashes of sunlight reflected by a mirror—he tried his hand at setting up a pigeon service. While some encouraging results were obtained, Miles reported that he was “troubled by a small hawk, which greatly disturbed the birds in their flight, occasionally destroying them.”

After a long dormancy, the US Army established a fully-fledged pigeon service upon the country’s entry into World War One. Impressed with the birds’ abilities during the War, Army officials decided to keep its pigeons afterwards, setting up a central station at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey and multiple lofts across the country and its territories. Before too long, Signal Corps pigeoneers assigned to care for the birds observed that hawks and falcons were plaguing their flocks, especially at the Panama Canal Zone lofts. There, one sergeant complained that his birds “are nearly always chased by hawks.” “Only recently . . . one of those big fellows dropped into the flock taking a very promising youngster and crippling [another],” he lamented in a letter to a fancier magazine.

To address this issue, officials at Fort Monmouth investigated a time-honored technique developed in China—pigeon whistles. As their name suggests, pigeon whistles are whistles that are attached to the birds before a flight. As the pigeons fly, air passes through the whistle, emitting a unique sound, not unlike the mechanical hum of a drone. Dating back to the Song Dynasty (960-1279 C.E.), they originated as a way for the military to send signals during war, but pigeon fanciers soon discovered they repelled birds of prey. Two types of whistles had been developed over the years. The former resembles a sort of panflute, with up to five bamboo tubes placed side-by-side, while the latter is made from a gourd, bearing a mouthpiece and around ten to twelve holes.

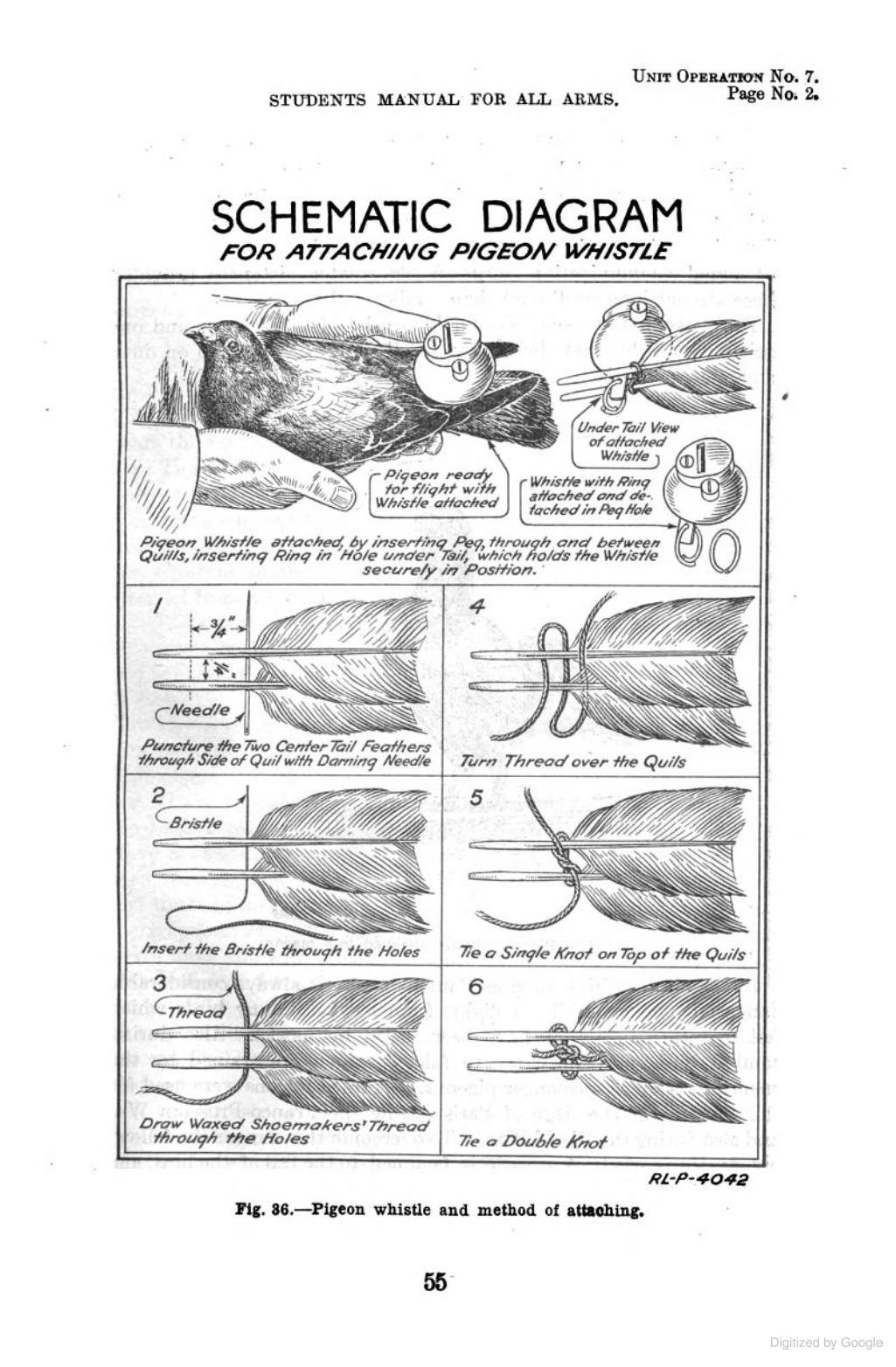

The Signal Corps imported a number of the whistles from China for use at Fort Monmouth. Throughout the ‘20s, pigeoneers experimented with the whistles. In the 1924 edition of the Army’s pigeoneer manual, soldiers were instructed to use pigeon whistles to ward off hawks. A detailed schematic explained how to install the device: a pigeoneer would need to pierce the bird’s two center tail feathers through the side with a needle, thread a piece of string through the holes, and tie a double knot on top of the quills. From this base, a whistle could be secured to the pigeon for as long as the pigeoneer desired. The manual, nevertheless, noted that the whistle was still a work in process—”Experiments are being carried on to determine the actual value of the whistle.”

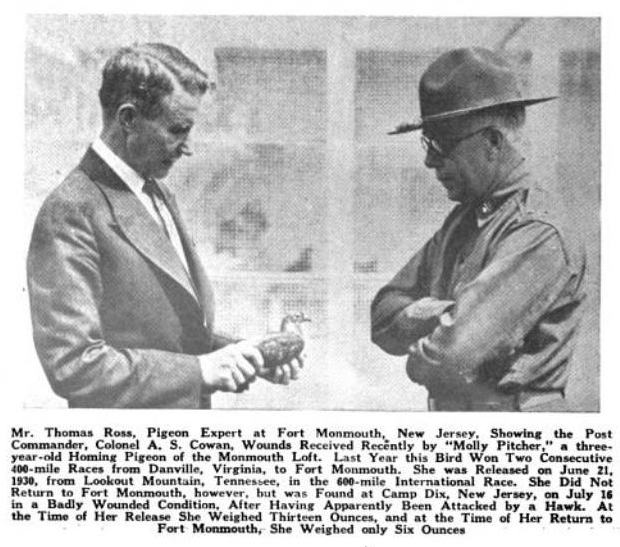

In spite of these efforts, officers at Fort Monmouth reported in August 1930 that the experiments had not proved successful. They undoubtedly had a fresh incident in mind. Just two months earlier, a hawk had brutally attacked one of the Signal Corps’ finest pigeons, Molly Pitcher, a three-year-old pigeon that had beaten over 3,000 birds in competition races. Molly had been released in a 600-mile International Race near Chattanooga, Tennessee on June 21st, but failed to show at her loft. On July 16th, she was spotted at nearby Camp Dix in New Jersey, walking between tents and unable to fly. Her trainer picked Molly up in person, noting that she had been severely wounded by a hawk. Although she recovered, Molly’s left wing remained permanently limp, ending her days as a flyer for Uncle Sam.

This seemed to inaugurate an unfortunate trend, with two unprecedented raids occurring within weeks of each other in 1932. In February, a hawk spotted a flock of Signal Corps pigeons out on an exercise flight. It followed them back and flew through the entrance trap into the loft—a feat never before accomplished by a raptor. Suddenly, over 100 birds were in extreme danger, including war heroes Mocker and Spike. The hawk instantly seized the Pride of Monmouth—a prize-winning homer who was being used in experimental flights along the earth’s magnetic meridian—and tore off his head. Before the hawk could do further damage, a sergeant who happened to be in the loft bashed it over the head with a stick. Dazed momentarily, the hawk then attacked the sergeant, scratching his arms and hands until he knocked the bird out. One the largest hawks ever to be seen at the Fort, it was put on display in a cage.

Just weeks later, in April, a group of night-flying pigeons were about to enter their loft when a large owl swooped down and grabbed Evening Star, one of the younger night-flyers. The owl tore up the pigeon’s back so badly that it died a few moments later. A private dashed off into the barracks to grab a shotgun and shot the owl after it had landed in a tree. Never before had an owl terrorized the Fort’s pigeons. As experiments with night-flying were a priority, this was a new risk for which the Signal Corps was ill-prepared.

Fed up with these ambushes, Colonel Arthur S. Cowan, the commanding officer of the Fort, immediately ordered that an armed guard be posted outside the pigeon lofts whenever the pigeons were in flight, day or night. Wielding a shotgun, the guard would patrol the areas around lofts on the lookout for hawks during the day and owls at night. In spite of this new measure, it appears that experiments with pigeon whistles continued unabated—in 1938, the Signal Corps announced that it would add them to the Pigeon Service’s wartime equipment.

During World War II, the US Army worried that birds of prey, whether wild or in the employ of the enemy, would be a greater danger than bullets or shrapnel. “So far in the Philippines,” reported one soldier, “hawks have proved to be a greater enemy of the pigeons” than the Japanese. Each Army loft was provided with a 12-gauge shotgun. Breeding efforts focused on producing dark-feathered birds, as those with lighter plumage were deemed “hawk-bait.” It’s unclear if pigeon whistles were still being used—a Signal Corps field manual from 1944 does not mention them.

Hawks continued to menace the Signal Corps’ pigeons until the unit was disbanded in 1957. Experiments testing the pigeons’ abilities to function in extreme cold during the winter of 1949-50 were derailed when Arctic falcons decimated their ranks. In spring 1952, a Signal Corps general gave a press conference about the pigeons’ activities in the Korean War. Once again, they had encountered their old enemy. “Hawks seem to find out where pigeons are stationed and hang around. . . . Our soldiers have to get out with shotguns,” he reported.

In spite of these repeated assaults, the Pigeon Service performed admirably in three major conflicts. It’s a testament to the resilience of the pigeons and pigeoneers that these calamities did not render the Service ineffective.

Sources:

- “Army Signal Corps Maintains School for Carrier Pigeons,” The Transcript-Telegram, Aug. 18, 1930, at 8.

- Bergne, Thomas, “Results of Night Flying in the Canal Zone,” The American Pigeon Journal, Vol. XII, No. 2, February 1923, at 91.

- Burkhimer, William, Memoir on The Use of Homing Pigeons for Military Purposes, at 8, 10 (1882).

- Eubanks, L.L. “Pigeon Whistles,” The Calgary Herald, Dec. 28, 1929, at 29.

- Farneti, Milo, “Army Still Makes Use of Pigeons,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Mar. 4, 1952, at 6.

- Hunter, Rex, “On Wings and a Prayer,” The Nebraska State Journal, Jul. 7, 1944, at 8.

- “Molly Pitcher, US Army Pigeon, Gets Radio Publicity,” The Bangor Maine, Jul. 29, 1930, at 20.

- “Owl Slashes Prized Pigeon; Fort Monmouth Posts Guard,” Asbury Park Press, Apr. 9, 1932, at 1-2.

- “Pigeon Hawk Slaughters Pride of Monmouth After Pursuing Birds Into Loft,” The Daily Record, Feb. 3, 1932, at 1.

- “Pigeons Save Lives in War Against Japan,” The Indianapolis News, Aug. 16, 1945, at 34.

- Sperry, James, “The Homing Pigeon,” Veterinary Bulletin for the Veterinary Corps, Vol. XI, No. 4, Apr. 11, 1923, at 251.

- “The Army’s Winged Messenger,” U.S. Army Recruiting News, Vol. XII, No. 23, Dec. 1, 1930, at 7.

- “Through the Telescope,” U.S. Army Recruiting News, Vol. XII, No. 16, Aug. 15, 1930, at 12.

- United States Army, The Pigeoneer, at 55-56 (1924).

- “Vivid Tale of New Aerial Foe Combat Told by Army Man,” The News, Feb. 4, 1932, at 10.

- “War Hero Pigeons No Longer Active,” The Evening Star, Sep. 28, 1930, at 10.

- “Whistles Added to Army Pigeon War Equipment,” The Springfield News-Leader, Sep. 16, 1938, at 14.

3 responses to “Birds of Prey vs. Pigeons of War”

Very interesting. So what was the average weight of the pigeon whistles? It seems like these devices would weigh the animals down.

LikeLike

Great question! According to a newspaper account from a person who inspected a few, the largest one was the size of a man’s fist and weighed only an ounce.

Pigeons can carry up to 2.5 ounces on their backs, so assuming the message holder clocked in at 1.5 ounces, the whistle wouldn’t weigh the bird down too badly.

Source:

“Fair Throngs Marvel at 1,000 Year-Old Pigeon Whistles Used to Protect Army Birds,” The Bulletin, Oct. 21, 1923, at 14.

LikeLike

[…] Birds of Prey vs. Pigeons of War. (2022, July 29). Pigeons of War. https://pigeons-of-war.com/2022/07/29/birds-of-prey-vs-pigeons-of-war/ […]

LikeLike