With origins in Northern Africa and the Middle East, homing pigeons clearly aren’t meant to be in the Arctic. Yet, these birds have repeatedly found themselves recruited for service in one of the coldest, most inhospitable regions on the planet. This week, we’ll take a look at the US Army’s attempts to prepare its Pigeon Service for Arctic operations.

Throughout its history, the abilities of the United States Army’s Pigeon Service would be tested in a variety of climes. The Great War saw the birds serve mainly in the temperate climate of continental Europe, while in the Inter-War Period, the Army erected lofts in the Panama Canal Zone, Hawaii, and the Philippine Islands, where hot weather was the norm. But how would the Army’s birds perform in places where cold weather was the default? This was an important concern, as the United States shares a border with an Arctic nation (Canada) and possesses its own Arctic territory (Alaska). Bearing this in mind, Army officials embarked on a multi-year process to gauge how its pigeons would function in the Arctic.

An opportunity to expose the Army’s Pigeon Service to extreme cold arose in Alaska in the early ‘40s. The US military had begun fortifying the region a decade earlier, after years of neglect. The Army Air Corps received authorization from Congress to construct a research airfield for cold weather testing near Fairbanks, Alaska. Built in 1940, the Ladd Army Airfield focused largely on testing aircraft performance and maintenance in freezing temperatures. Researchers also explored other aspects of Arctic operations, including communications. As pigeons were still being used by pilots for emergency communication, this meant they were a natural subject for experimentation.

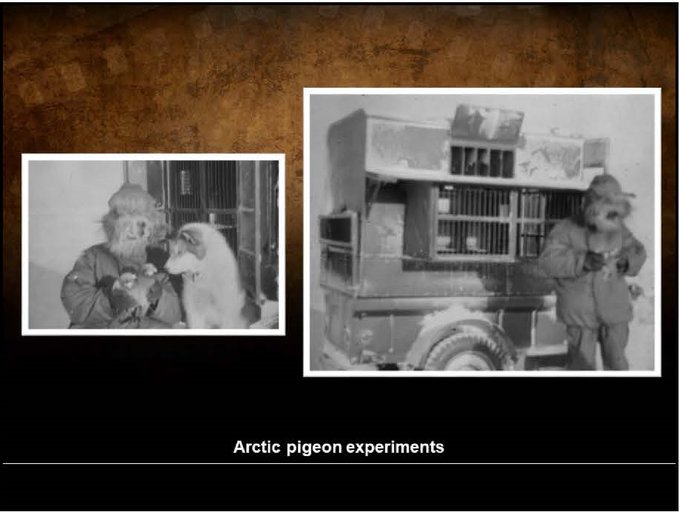

To that end, a shipment of homing pigeons from Fort Monmouth, New Jersey arrived in December 1941 for cold weather training. A newspaper article published at that time mentioned that the pigeons would be trained to return to mobile lofts under frigid conditions. A portion of the birds’ training would also involve being released from Army bomber planes. Signal Corps Pigeoneers traveling with the pigeons claimed the birds would perform well in cold weather given that “their body temperature is as high as 107 degrees.” Nevertheless, to ensure the pigeons’ wellbeing, the mobile lofts would be heated and the birds allowed to hang out in a stationary loft that had been erected near the base’s radio transmitter. An assessment of how the birds performed in the cold weather is not readily available, but evidently, the experiment ran for some time—from November 1941 through October 1943, approximately 275 pigeons passed through Ladd Field and other military installations in Alaska.

Following a brief pause during the Second World War, the US Army re-examined the need for Arctic operations, now that the Soviet Union had become the enemy. During the early years of the Cold War, the US would focus on training its troops in the Canadian Arctic. An ideal site was Fort Churchill, an American military facility situated on the Hudson Bay in the northeastern corner of Manitoba. Temperatures in that area had been known to drop to 67 degrees below zero.

In the winter of 1948, a consignment of Signal Corps pigeons found themselves bound for the Great White North. Army officials took them on flights for several weeks in subzero temperatures. Initial results were not promising. In spite of weeks of training, the Army’s birds managed to fly no more than 25 miles in a day—far below the 500 miles a day the birds flew when south of the border. Major Otto Meyer, the Chief of the Army’s Pigeon Service, summarized the results. “They fly at greatly reduced speeds in the northland and navigate smaller distances,” Meyer stated to a Canadian newspaper. He speculated that sunspots—rather than cold weather—might be behind these issues. “We have found that the magnetic force of the earth is one of the most important factors in giving the pigeon its uncanny ability to return to its starting point,” Meyer explained, “but the sunspots up north tend to disrupt the pigeon’s flight and lessen its speed.”

To determine why the Army’s pigeons were having such trouble performing in cold weather, 70 pigeons and eight Pigeoneers traveled to Fort Churchill in November 1949 for additional testing. Army researchers also wanted to crack the mystery behind the pigeons’ homing abilities, seeking to use this understanding to develop pilotless ships and airplanes. Over 7 weeks, the pigeons were tested on flights that ranged from a quarter of a mile to 10 miles. Each bird had been trained to make flights up to 200 miles back in the States. Unfortunately, the group experienced high mortality rates. Of the 70, 51 had died by the middle of January. Meyer blamed over half the deaths on hawks. “Hawks are the greatest enemy of the pigeon in the north.” Foxes, cold weather, and training accidents were responsible for the rest. For those that survived, the intense cold hampered the pigeons’ flying abilities. “Taken out several miles and released,” reported the Calgary Herald, “they would simply scoot back into the loft instead of heading for home.”

Despite two years of bad results, Meyer remained undaunted. He planned to return to Fort Churchill with more Signal Corps pigeons the following year. As a baseline against which to compare their performances, Meyer sought pigeons born and bred in Western Canada, believing that these birds would be more accustomed to the severe climate. By spring 1950, he’d reached an agreement with pigeon fanciers in Edmonton for them to supply the Army with their birds. One fancier expressed doubt that his birds would fare any differently. “When the temperature drops below zero, human beings are happy to stay at home. Pigeons are no different.” In November, 70 more Army birds trekked northward for a third round of experiments, accompanied by specialized Arctic equipment such as hot water feeders, newly designed lofts, and training baskets. Frustratingly, the results of this round of testing cannot be found online, but suffice it to say, they must have been disappointing, as the Signal Corps never again sent its pigeons north.

In retrospect, it seems quite obvious that pigeons are not cut out for Arctic service. Still, one can’t blame the Army for trying to see if it was possible. After all, pigeons have proven their merit in North African deserts and Southeast Asian jungles. Although the pigeons’ flying capabilities were greatly reduced in the bitter cold, the birds gave all they could for the cause. For this reason, we at Pigeons of War feel this chapter in the US Army’s Pigeon Service is worthy of commemoration.

Sources:

- “Aeronautics Experts Test Homing Pigeons,” Nanaimo Daily News, Dec. 6, 1949, at 1

- Coates, John B.,The United States Army Veterinary Service in World War II, at 233 (1961).

- “Hawks Kill Many U.S. Army Carrier Pigeons,” Calgary Herald, Jan. 11, 1950, at 28.

- Matthew S. Wiseman “The Development of Cold War Soldiery: Acclimatisation Research and Military Indoctrination in the Canadian Arctic, 1947-1953.” Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015).

- “Pigeons Sent to Arctic Post,” Asbury Park Press, Nov. 21, 1950, at 2.

- Price, Kathy, The World War II Heritage of Ladd Field, Fairbanks, Alaska, at 5 – 7 (2004).

- Shiels, Bob, “Homing Pigeons Here Trained for Defences,” Edmonton Journal, May 31, 1950, at 3.

- “Study Flight Habits of Homing Pigeons,” The Ottawa Journal, Jan. 21, 1950, at 29.

- “Winged Squadron Prepares for Takeoff at Ladd Field,” Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, Dec. 20, 1941, at 1.

One response to “Pigeons in the Arctic, Part II: Cold Weather Training”

[…] continued to menace the Signal Corps’ pigeons until the unit was disbanded in 1957. Experiments testing the pigeons’ abilities to function in extreme cold during the winter of 1949-… In spring 1952, a Signal Corps general gave a press conference about the pigeons’ activities in […]

LikeLike