With origins in Northern Africa and the Middle East, homing pigeons clearly aren’t meant to be in the Arctic. Yet, these birds have repeatedly found themselves recruited for service in one of the coldest, most inhospitable regions on the planet. This week, we’ll take a look at two polar expeditions—one civilian, one military—involving flights near the North Pole. In both these missions, explorers brought pigeons along with them to keep the world informed of their progress.

Throughout the nineteenth century, explorers angled to be the first to “discover” the North Pole. Nearly all of these trips involved traveling toward the Pole via ship or dogsled. However, in 1895, Swedish balloonist Salomon August Andrée announced to a packed lecture hall a new strategy—he intended to fly over the North Pole in a hydrogen balloon. As Andrée envisioned it, he and his crew would lift off from an island within the Svalbard archipelago, and steer the balloon over the Bering Strait toward either Russia, Canada, or Alaska, passing over the North Pole in the process. His scheme attracted attention from the Royal Swedish Academy, which agreed to fund the expedition. Andrée also received monetary contributions from King Oskar II and Alfred Nobel, both of whom were eager to see Sweden best its Arctic peers by being the first nation to reach the North Pole.

Over the next two years, Andrée diligently prepared for the voyage. He developed a dirigible balloon capable of holding a crew of three men plus provisions while staying aloft for 30 days. To communicate with the outside world, Andrée would carry with him 36 homing pigeons in wicker baskets. Donated by the Norwegian newspaper Aftonbladet, the birds had been raised in lofts in northern Norway. It was hoped that they would return to this area, bearing despatches and photographic negatives of Andrée’s progress. Printed instructions accompanying the messages would inform recipients to turn them over to the paper’s Stockholm officer.

On July 11th, Andrée launched the balloon from Danes Island, while the world waited with bated breath. On July 15th, one of the expedition’s pigeons alighted on the masthead of a Norwegian sealer vessel. The bird was shot and its message examined. It read:

“The Andrée Polar Expedition to the ‘Aftonbladet’, Stockholm. 13 July, 12.30 p.m., 82 deg. north latitude, 15 deg. 5 min. east longitude. Good journey eastwards, 10 deg. south. All goes well on board. This is the third message sent by pigeon. Andrée.”

This despatch was the last the world heard from Andrée for over 30 years. Although the message indicated that two other messages had been sent via pigeon, no other birds were ever found. In 1930, a Norwegian scientific mission discovered the remains of the expedition on Kvitøya. From reading Andrée’s diary, they learned that the balloon had crashed on pack ice after two days of heavy winds. From there, the crew slowly headed south across the drifting icescape as the Arctic winter closed in on them. By October 1897, all three men had perished.

In April 1909, United States naval officer Lieutenant Robert Peary allegedly reached the North Pole. Even though the Pole had been found, however, the United States Navy still expressed an interest in aerially surveying the area, given that military and commercial flights would inevitably cross the Pole. In 1925, the Navy agreed to provide planes and officers to the MacMillian Arctic Expedition, a joint civilian-military excursion headed by renowned polar explorer Donald MacMillan. The civilian scientists, affiliated with the National Geographic Society, planned to study the natural phenomenon of the area, while naval aviators would survey the uncharted ice lying between Alaska and the North Pole, seeking to verify land claims made by prior polar explorers. The plan was for the explorers to make base at the port of Etah—a small village on Greenland’s northwestern coast about 700 miles south of the Pole—during the Arctic summer season. From there, the naval aviators would make flights over the uncharted areas.

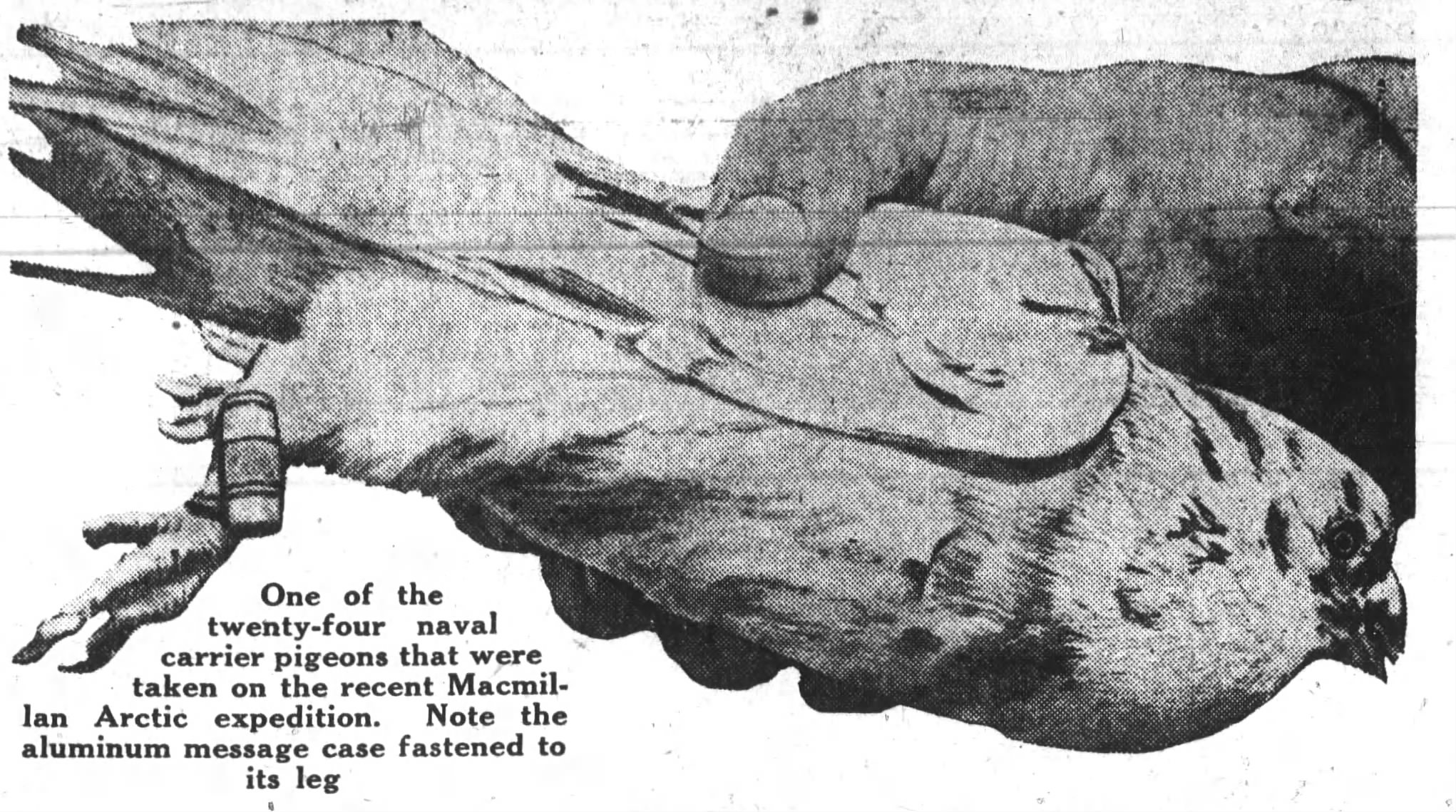

In preparing for the polar flights, the Navy, like Andrée, opted to bring along homing pigeons. The time, though, the birds would serve as backup communication, allowing pilots to contact officials on the ground in the event the plane’s radio failed or the plane crashed. In advance of the trip, 24 pigeons at the Naval Air Station Anacostia in Washington, D.C. were selected for polar training. The birds were put on a special diet of dried peas and vetch that was designed “to strengthen their muscles and put fat on their bodies to withstand the cold.” Trainers designed a 700-mile training course stretching from Washington to Chicago, Illinois, over which the birds were trained in 100-mile stretches at a time. The pigeons maintained an impressive flight speed averaging 50 mph over 500 miles. Naval officials weren’t too worried about the severe Arctic climate’s effects on the birds—”[Pigeons] have been flown successfully in Winter in northern Minnesota and Canada,” they remarked to the press, “when the mercury was lower than it probably will be in the Arctic regions this Summer.”

Ultimately, the group of 24 pigeons was winnowed down to the 10 best performing birds. These elite birds had the requisite pedigrees and experience for surviving in the Arctic’s severe climate. All of them had won prizes for flights, and several had experience flying from New Orleans to D.C, a distance of over 1000 miles. Their stamina was impressive as well. Each of these birds had flown 500 miles in a single day. Two of them—dubbed “Lightening” and “Admiral” in the press—had flown 1000 miles in a day. “[I]f history is to be made by pigeons in the Polar regions, ” Chief Quartermaster Henry Kubec asserted to the media,” these two will play an important part in it.”

The pigeons were loaded up in a crate and sent by express from D.C. to the naval yard in Boston. Accompanying the birds were 1400 pounds of pigeon feed and an assortment of baskets, bathtubs, drinking fountains, message books, and flying instructions. Curiously, several pounds of tobacco had been set aside for each pigeon—newspapers reported jocularly that it would “provide an ample chewing ration for the birds,” but in reality, tobacco stems make for excellent nesting material, as the stems repel vermin and keep eggs and squabs from falling out of the nest. The supplies were enough to last a year, so that in case “the steamer becomes frozen in the grip of the Arctic the birds will not suffer while waiting for the ice to break up.”

When the bird arrived at the Boston Navy Yard, a pigeon trainer introduced them to the naval aviators. The trainer explained in detail how to feed the birds and the proper temperature for their baths. The birds and their supplies were eventually loaded up with the Navy’s planes on board the SS Peary, a former Canadian minesweeper. The expedition began in earnest on June 20th when the Peary and the scientists’ ship the Bowdoin departed Maine. At a brief stop in Sydney, Nova Scotia, a pigeon trivia contest was held for the benefit of the local children. Officers aboard the Peary awarded the winner three eggs recently laid by the ship’s birds. The birds’ caretaker, Chief Aerographer Albert Francis, thought this would be a good diversion, given that the city was in the throes of a local mine strike—he had planned to eat the eggs for breakfast, anyway.

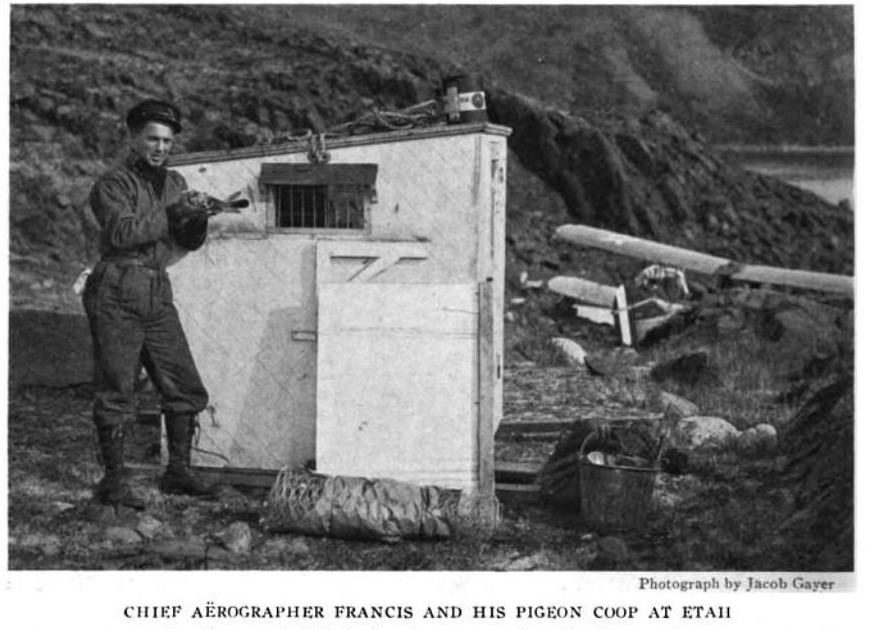

After weeks battling icefields, the explorers made it to Etah on August 1st. A pigeon coop was quickly set up on a hill overlooking a beach. On August 3rd, Commander Richard Byrd, the officer in charge of the aviators, informed the media via radio dispatch of the pigeons’ wellbeing. “Pigeons are in good shape. Will take them ashore tomorrow to orientate them.” The birds had also continued laying eggs unabated. “Two pairs of pigeons are nesting,” Byrd reported.

On August 4th, the birds were shut up inside the Etah coop for a few days so they would grow familiar with their environment. Byrd also claimed, rather condescendly, that the pigeons had been frightened by the Inuit crew’s sealskin clothing and needed this time to recuperate. For their training regimen, Francis intended to take the birds to points in the surrounding country and sea and release them on short flights back to the base. As the explorers wanted to set up a sub-base 250 miles away from Etah, it was hoped that the pigeons eventually would make regular flights between the facilities, serving as backup communication should the radio equipment break down.

Late in the afternoon of August 10th, Francis released the pigeons on their first flight from the base. Two hens immediately returned, seeking to care for their eggs. Two more had come back by morning, for a total of 4 returnees. Byrd speculated more might fly back as they grew hungry, but none ever did. After several days, Francis determined that Arctic falcons had eaten all the other birds. The likely culprit was the gyrfalcon, an extremely large falcon that thrives in the High Arctic. In spite of all their training, the Navy’s pigeons could not escape their perennial foe. “[P]igeons are not practicable for communication purposes in that part of the Arctic,” Byrd concluded in a post-expedition account.

For the remainder of the expedition, the aviators had mixed success in flying over the Arctic. The expedition headed back home in October to great acclaim. Although the pigeons didn’t live up to the Navy’s expectations, readers back in the US were nonetheless inspired by them. Around the end of August, a 12-year-old boy wrote to the National Geographic Society to see if he could get “one of the pigeons our dear Mr. MacMillan took up north with him.” A budding pigeon fancier, he desired a bird “who has succeeded in flight for I want my pet to have a name for himself.” Even well into 1926, newspapers were still publishing pictures of the birds.

In each of the above Arctic excursions, the pigeons that tagged along all had something in common—they were not the focus of the missions. As the US military gained a foothold in the Arctic, though, pigeons would receive special attention. Next week, we’ll examine the US Army’s efforts to acclimate its pigeon service to the Arctic.

Sources:

- “Andrée’s Arctic Balloon Expedition.” Wikipedia, 15 June 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andr%C3%A9e%27s_Arctic_balloon_expedition

- Byrd, Richard, “Flying Over the Arctic,” The National Geographic Magazine, July to December 1925 Vol. XLVIII, at 519-20, at 524.

- Byrd, Richard, “Headed for the North Pole,” US Air Services, Sept. 1925, Vol. 10, No. 9, at 42.

- “Chewing Tobacco on Pigeons’ Menu While in Arctic,” Evening Star, May 16, 1925, at 16.

- “Conditions at Etah Are Told,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Aug. 3, 1925, at 1.

- Hiam, C. Michael. “Flight of the Polar Eagle: Journey to the North Pole.” HistoryNet, 11 July 2019, https://www.historynet.com/flight-polar-eagle-journey-north-pole/

- “Homing Pigeons for the Peary on Its Expedition North,” The Boston Globe, Jun. 16, 1925, at 11.

- “Inside the Macmillan Arctic Expedition of 1925.” Navy Times, 8 May 2019, https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/05/08/inside-the-macmillan-arctic-expedition-of-1925/#:~:text=In%201925%20an%20unusual%20first,young%20American%20adventurer%2C%20Lincoln%20Ellsworth.

- “Little Boy Wants MacMillan Pigeon,” The Buffalo Evening News, Aug. 31, 1925, at 20.

- “MacMillan Could Not Select Base,” The Montreal Star, Aug. 10, 1925, at 1.

- “Peary Arrived at Sydney, N.S.,” The Gazette, Jun. 24, 1925, at 8.

- “Pigeons Training for Arctic Flight,” The Evening Star, May 29, 1925, at 27.

- “Planes Visit Camp Where 18 of Greely’s Men Died,” The Boston Globe, Aug. 10, 1925, at 2.

- “The Peary Drops Anchor in Sidney, N. B. Harbor,” The Sun-Journal, Jun. 24, 1925, at 1.

2 responses to “Pigeons in the Arctic, Part I: Polar Expeditions”

What about Antarctica? Did explorers bring homing pigeons there as well?

LikeLike

That’s a really good question! I haven’t researched whether pigeons were brought on expeditions to Antarctica, so I don’t know. Wish I had a more satisfying answer for you.

LikeLike