This past Monday was the 78th anniversary of the Allied invasion of Normandy, popularly known as D-Day. A monumental achievement, the invasion changed the course of World War II, laying the groundwork for the liberation of France. An often ignored aspect of that day is the role pigeons played in the landings. Today, we look at one of those birds, Gustav

Gustav, a grizzle-colored male, was born in Cosham, Hampshire, England in 1942. His keeper, Frederick Jackson, was a member of the National Pigeon Service, a civilian group of fanciers who raised pigeons for war effort. When he was a few months old, the Royal Air Force (RAF)—which supplied pilots with birds to use in emergency situations— requisitioned Gustav for military service. He moved into the loft at the RAF’s base on Thorney Island, near Portsmouth and found himself under the charge of Sergeant Harry Halsey.

Officially known as NPS.42.31066, Gustav soon earned a reputation as a reliable flyer. Impressed with his skill, Gustav’s superiors recruited him for a series of special missions. In 1941, British military intelligence had developed a top-secret program for making contact with members of the resistance across Nazi-occupied Europe. Because a pigeon raised in Southern England can fly back from Northern France, Belgium. the Netherlands, and Denmark, intelligence officials determined that it would be beneficial to provide citizens of these countries with British pigeons. Between 1941 and 1945, RAF pilots dropped approximately 16,000 boxes of pigeons in these areas. Each box contained sheets of thin paper, a special pencil, a tube for storing the message, and instructions on how to write a message. The gambit paid off—over 50 percent of the received messages provided British intelligence with useful information about the enemy.

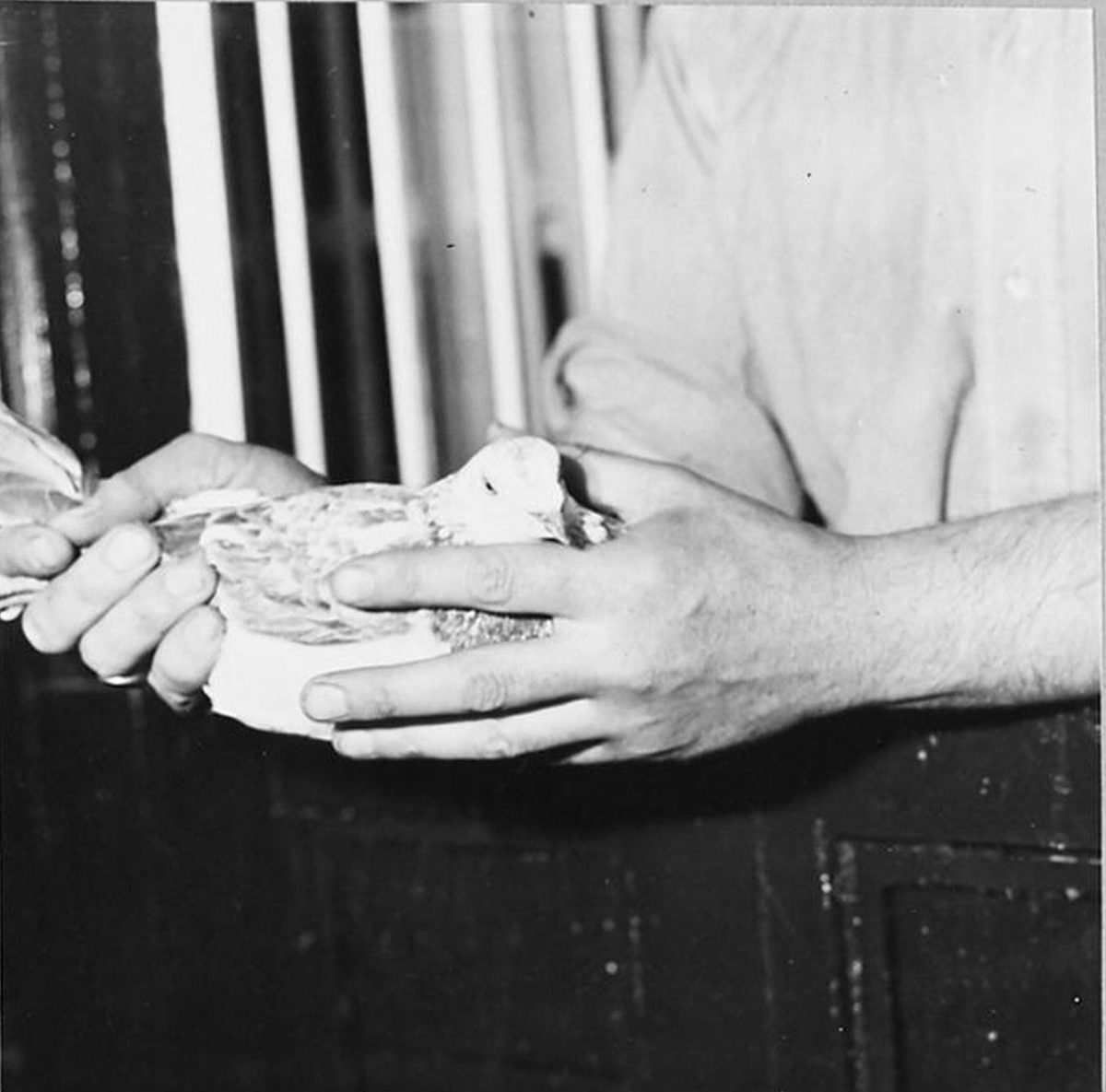

For two years, Gustav was repeatedly dropped off in Belgium. Each time, he flew back to his loft bearing important messages from the Belgian resistance. The details of these missions aren’t well known, which isn’t surprising, given the sensitivity of the information. Gustav’s courage prompted RAF officials to select him for another mission: Operation Overlord, the planned invasion of German-occupied France. Officials had selected hundreds of elite birds for use during the invasion. The birds would be presented to the troops in wicker baskets and used for carrying ammunition status reports and undeveloped film negatives as well as delivering messages when radio silence prevailed or other means of communication failed.

Instead of being loaned out to soldiers, however, Gustav would be paired up with a journalist—perhaps he was too valuable to be taken out onto the battlefield. On the morning of June 6th, 1944, an RAF commander approached Reuters correspondent Montague Taylor and gave him “a basket of four pigeons, complete with food and message carrying equipment.” The team clambered on board an Allied Land Ship Tank and settled in 20 miles away from the Normandy coast. As he watched the troops land on the beaches, Taylor hurriedly scribbled down a despatch and stuffed it into Gustav’s leg holder. At 8:30 am, he released the bird from the ship

The challenges Gustav encountered during his journey were real and substantial. The climate that day was unfavorable for flying. A fierce headwind was blowing at 30 to 50 mph, making for stiff resistance. The sun was shrouded by clouds, a major issue for homing pigeons, as they use the sun to help find their way. German-trained hawks and sharpshooters were also in the area, searching for pigeons flying overhead. But Gustav rose to the occasion. Flying non-stop over 150 miles for 5 hours and 16 minutes, Gustav entered his loft on Thorney Island at 1:46 pm. His message read:

“We are just 20 miles or so off the beaches. First assault troops landed 0750. Signal says no interference from enemy gunfire on beach. Passage uneventful. Steaming steadily in formation. Lightnings, Typhoons, Fortresses crossing since 0545. No enemy aircraft seen.”

Officials immediately telephoned London with the news. This despatch was the first report received in Britain of the Normandy landings. It was appropriate that Reuters had used a pigeon to obtain its exclusive. Nearly 100 years earlier, the news agency’s founder, Paul Reuter, had trained a flock of 45 pigeons to deliver news and stock prices between Brussels and Aachen, beating the railroad by six hours. The success of this venture prompted Reuter to open the first Reuters news room in London a year later.

For his actions, Gustav was awarded the Dickin medal, the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross. The ceremony took place a few months later, November 18th. The wife of the First Lord of the Admiralty hung the ribbon around Gustav’s neck and gave him a peck on the cheek. Another veteran of D-Day was also present at this ceremony—Paddy. Described by the press as “[a]n Irish pigeon trained in England by a Scotsman with a Welsh assistant,” Paddy held the record for the fastest flight back to Britain that day. Flying back to his loft at the RAF Base in Hurn, he traveled 230 miles in 4 hours, 50 minutes, a speed of 46 mph. A few years later in 1947, one more pigeon would receive a Dickin Medal for displaying mettle during Operation Overlord. The pigeon, fittingly named the Duke of Normandy, had delivered a critical despatch from the paratroopers of the 21st Army Group, who had landed behind enemy lines a few days earlier.

Gustav’s heroism earned him a soft berth for the remainder of the War. After the cessation of hostilities, he was returned to his original keeper, Frederick Jackson. Reports are mixed as to his fate afterwards. One story has him living in Jackson’s loft for many years, ultimately dying of old age. The other presents a much more tragic ending: while cleaning out his loft, Jackson accidentally stepped on him.

Gustav’s luster has only grown in the years since his achievements. His story partially inspired the computer-animated film Valiant, released in 2005—the same year Gustav’s Dickin Medal was publicly displayed at the D-Day Museum in Portsmouth. In 2013, a short film recreating Gustav’s actions on D-Day debuted at the Cannes Film Festival. The Imperial War Museum recently recognized Gustav as the greatest pigeon to have served the United Kingdom. We at Pigeons of War cannot disagree with that assessment.

Sources:

- Fletcher, Zita Ballinger. “How Gustav the Pigeon Broke the First News of the D-Day Landings.” HistoryNet, 7 Apr. 2022, https://www.historynet.com/how-gustav-the-pigeon-broke-the-first-news-of-the-d-day-landings/

- “Hero Pigeon’s WWII Medal on Show.” BBC News, 1 June 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/hampshire/4600865.stm

- Hutton, Robin, War Animals: The Unsung Heroes of World War II, at 292

- “Liberation of Europe: Pigeon Brings.” Imperial War Museums, https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections.

- Use of Pigeons in the Invasion of France, July 27, 1944.

- “Vital Role of Gustav the Pigeon.” The Northern Echo, 2 June 2004, https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/6989082.vital-role-gustav-pigeon/.

One response to “Gustav: D-Day’s Finest Pigeon”

[…] Pigeons of War, we’ve devoted several articles to famous war pigeons. We’ve written about Gustav and President Wilson, for instance, both of whom spent their formative years in the military. […]

LikeLike