To the victor go the spoils. That pithy phrase has justified the wholesale seizure of property during wartime for millennia. Throughout the Great War, both the Allies and the Central Powers confiscated military equipment from one another when the opportunity presented itself. Trucks, ships, airplanes—each captured piece of equipment had the potential to bolster militaries depleted of resources. As emergency communication devices, pigeons were no exception.

As the War turned decisively in the Allies favor in the latter half of 1918, the Germans often left their pigeons behind as they abandoned their positions. On August 9th, a Canadian regiment captured a mobile loft filled with German pigeons in Folies, France. It was turned over to the London Zoo for public viewing. Six months later, a columnist toured the former Brieftauben Station No. 708, which looked “like an old grey caravan sadly needing a coat of pain.” “Twenty or more pigeons were flying back and forth,” she reported, “excited at the intrusion of a stranger in their camp.” Zoo officials informed her that the young pigeons would soon be flying in a few weeks, while the adults were permanently grounded, since they might fly back to Germany. This fear was realized three years later when two escaped from the Zoo and flew back to Berlin.

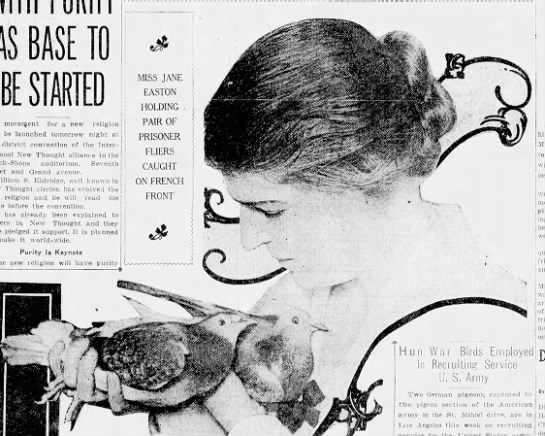

American forces, too, soon found their ranks swelling with enemy pigeons. They came across a tranche of them during the Saint-Mihiel Offensive in September 1918. Eight birds were found in an abandoned loft when the Americans captured Montsec. Two more happened to land on an American loft; they had been searching for their home lofts, which had been set ablaze by fleeing Germans. The Yanks found even more birds during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which lasted from Sept. 26 to the end of the War. While searching through a German trench, the 28th Infantry Division found a basket with 10 pigeons inside. Later on, a group stumbled across an abandoned German loft and seized the birds as they returned. In a moment of serendipity, German aviators dropped a mated pair behind American lines via parachute, hoping that their spies might find them. Instead, doughboys found them and turned them over to the intelligence department.

At least 22 pigeon POWs (if not more) sailed home with the boys in 1919. They were displayed around the country to attract potential recruits to the Army’s Pigeon Section. Afterwards, some went into private lofts, while others were donated to zoos. But the Yanks seemed to have had more pragmatic concerns on their minds than their British peers. Many of the birds were integrated into the breeding program at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, the HQ of the Army’s Pigeon Section. A POW known as the “Blue Check Frill” produced some of the Army’s best flyers—one of his sons won first place in a prominent pigeon race. At some point, unfortunately, an overly-patriotic sergeant at Fort Monmouth determined that the German birds were unfit to associate with their American peers and released a flock of them over Philadelphia. Following this debacle, in 1922, Captain Ray Delhauer—a former officer in the Section who was now employed as its Pigeon Expert—transferred several of the German pigeons to Ross Field in Arcadia, California, the Army’s breeding station for the west coast. These birds were bred to supply pigeons to the Pacific Coast and the Hawaiian and Philippine territories. Three years later, the Army closed down the Ross Field lofts, opting to use birds from civilian fanciers. Most of the remaining German birds were sent back east to Fort Monmouth.

By 1930, only a few of the German prisoners were still living in America. One passed away that year, a spoil of the Meuse-Argonne. Unlike his colleagues, this bird had not spent his years in America as a guest of the government—Frank H. Hollmann, editor of the American Pigeon Journal, had cared for him in his private loft, taking him on lecture circuits. In spite of a shrapnel wound to his eye, the bird lived for 13 years. Upon his death, he was stuffed and presented to the Missouri State Museum at the Capitol building in Jefferson City. With his death, newspapers declared that only two German birds were left in the US, both of whom were in the possession of the Army.

The newspapers were a bit off, but still close. It appears that the Army had only one German bird while two were in private custody. Captain Delhauer still had the mated pair that the Germans had kindly dropped over American lines. Given the monikers Kaiser and Fraulein, the birds were living with Delhauer at his ranch in Ontario, California. Fraulein lived until 1934, while Kaiser passed in 1937. They contributed to Delhauer’s prized Chaffey strain—a naturally camouflaged bird that was later used in World War II.

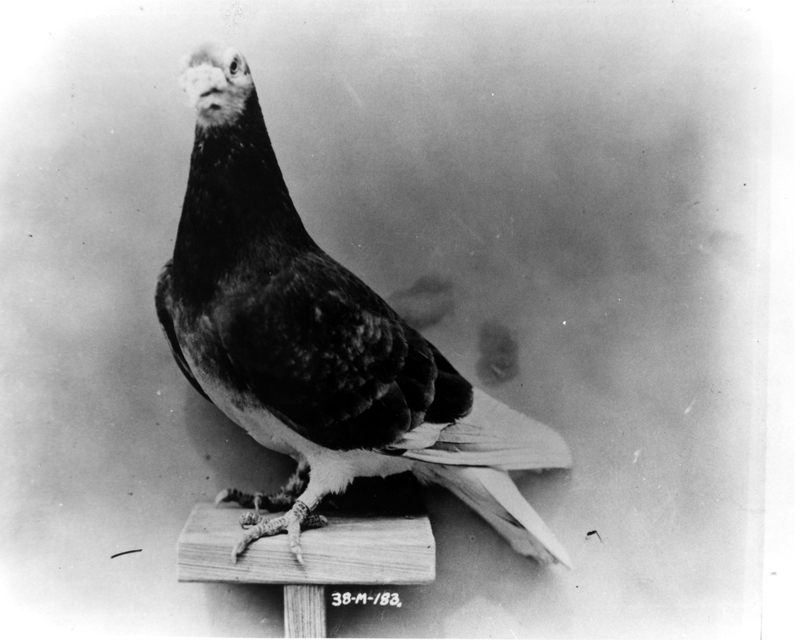

The Army’s last surviving POW pigeon—and perhaps the best known—was Kaiser. Captured by American troops in the Argonne, the bird was initially known as Rheingold, then was re-christened Wilhelm, which seems to have evolved into Kaiser by the ‘40s. Sporting a red-check coat, Kaiser was allegedly the only captured bird to come from a royal loft—in this case, the Royal Bavarian Lofts. Modern research, however, suggests that he was actually born in a private loft in Koblenz, which is in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate.

At the age of 20, Kaiser had outlived all of his fellow POWs. Given that the average life expectancy of a pigeon is 8 years, it was speculated that Kaiser would soon join his colleagues. But Kaiser showed no signs of slowing down. He continued producing champion heirs for the Army, many of whom served in World War II. In 1949, at 32 years old, he and a few veteran birds of the Second World War traveled to Washington, D.C. to witness the inauguration of President Harry Truman. On Halloween night that year, Kaiser finally died, having lived four times the normal lifespan of a pigeon. His body was stuffed and placed on display at the Smithsonian.

Although they were born in the enemy’s lofts, the pigeons captured by the Allies quickly adapted to their new homelands. They amused zoo goers, lounged around in private lofts, and even improved their host country’s military pigeon services. This resiliency is just further proof of the value pigeons add to militaries.

Sources:

- “A Canadian Woman in England,” Calgary Herald, Jan. 29, 1919, at 10.

- “Army Fosters Homing Birds,” The Los Angeles Times, Aug. 13, 1922, at 18.

- Blazich, Frank. “America’s Kaiser: How a Pigeon Served in Two World Wars.” National Museum of American History, 12 Feb. 2019, https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/kaiser.

- “Famous War Pigeons to Be Taken to New Jersey,” The Pomona Progress Bulletin, Jan. 22, 1925, at 6.

- “German Pigeons Have New Home,” Altoona Tribute, Aug. 28, 1920, at 3.

- “German Pigeon, War Captive, Is Enjoying Life,” Mason Valley News, Nov. 23, 1934, at 7.

- “Hold a War Bird Exhibit,” Kansas City Star, Aug. 15, 1919, at 4.

- “Lost War Pigeons Return,” El Paso Herald, Feb. 14, 1922, at 2.

- “Only Living Captive of Germans’ Pigeons Forgets War Days,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Jan. 15, 1933, at 12.

- “Racing Pigeon from World War Is Dead,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Sept. 16, 1932, at 14.

- “Three Pigeons Among Great War Heroes,” The Independent-Record, Jan. 27, 1929 at 15.

- “Two Captured German Pigeons Shown in L.A.” Los Angeles Evening Express, Jun 6, 1919, at 17.

- “Warrior-Pigeon Dies,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Dec. 5, 1937, at 14.

One response to “Pigeon POWs of the Great War”

[…] as they beat a hasty retreat from encroaching Allied forces. Many of these abandoned birds, as we’ve previously written about, were eagerly adopted by the Americans, who incorporated them into breeding programs back […]

LikeLike