The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 is perhaps the most well known instance of pigeons being used to carry information in and out of a city during a siege. But nearly 40 years earlier, the Dutch military used pigeons in a similar fashion during the Siege of Antwerp in 1832. In this post, we examine the role of pigeons in that conflict.

In the summer of 1830, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands witnessed a series of revolts in its southern provinces, an area comprising modern-day Belgium. Religious differences played a significant role: The Belgian provinces were primarily inhabited by Roman Catholics, while the northern Dutch provinces were dominated by Protestants. The Belgians also despised their lack of autonomy and underrepresentation in the Netherlands’ General Assembly. Inspired by the July Revolution in France, revolutionaries in Brussels took over the city in August and declared their independence from the Dutch King William. The uprising quickly spread to other cities in the Belgian Provinces over the ensuing weeks.

On September 23rd, Prince Frederick, the Commander-in-Chief of Dutch forces in Belgium, hoped to quell the rebellion by seizing Brussels from the revolutionaries. Facing fierce street fighting, the Prince withdrew his troops after four days and retreated to Antwerp. The choice of Antwerp seemed logical at the time. The city had remained loyal to the Dutch government. Moreover, Antwerp boasted extensive fortifications in its southern area. The centerpiece was the Citadel, a pentagon-shaped bastion fort situated in front of the Scheldt River. It could host thousands of soldiers and featured 114 pieces of artillery. Across the river, the Flemish Head and several other minor forts also contributed to the city’s defense, while also serving as ports for the Dutch Navy’s warships.

But as the month of October progressed, revolutionary fervor swept over Antwerp. General David Chassé, the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief and a veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, ordered his troops to take refuge in the Citadel. To protect the fort, the Dutch government dispatched several frigates and gunboats to implement a blockade on the Scheldt. Dutch naval officer Captain Jan Koopman was tasked with serving as a liaison between the fleet and the Citadel. On October 25th, Antwerp fell to Belgian insurgents, while the Citadel remained under Dutch control. A ceasefire was brokered between the revolutionaries and the Dutch troops, but the former broke it when they tried to seize an arsenal. In retaliation, the Citadel and the Dutch warships bombarded Antwerp until the Belgian insurgents withdrew from the town into the suburbs. The parties eventually entered into an uneasy truce, with General Chassé to remain at the Citadel until he received orders from King William to yield.

With the Citadel and the Dutch flotilla now surrounded by an unfriendly population, military officials needed a proper communication network to ensure the flow of information in and out of the garrison. A mail barge allowed for correspondence to be delivered to and from the Citadel, but this method was time consuming. For urgent messages, a different medium had to be found.

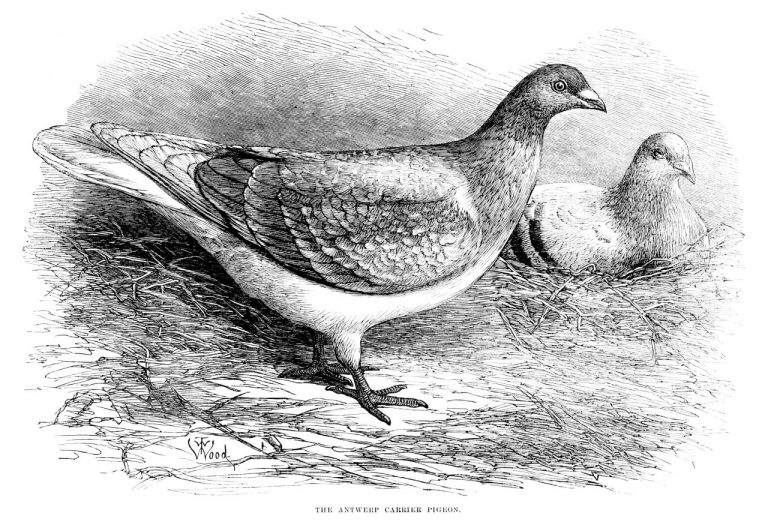

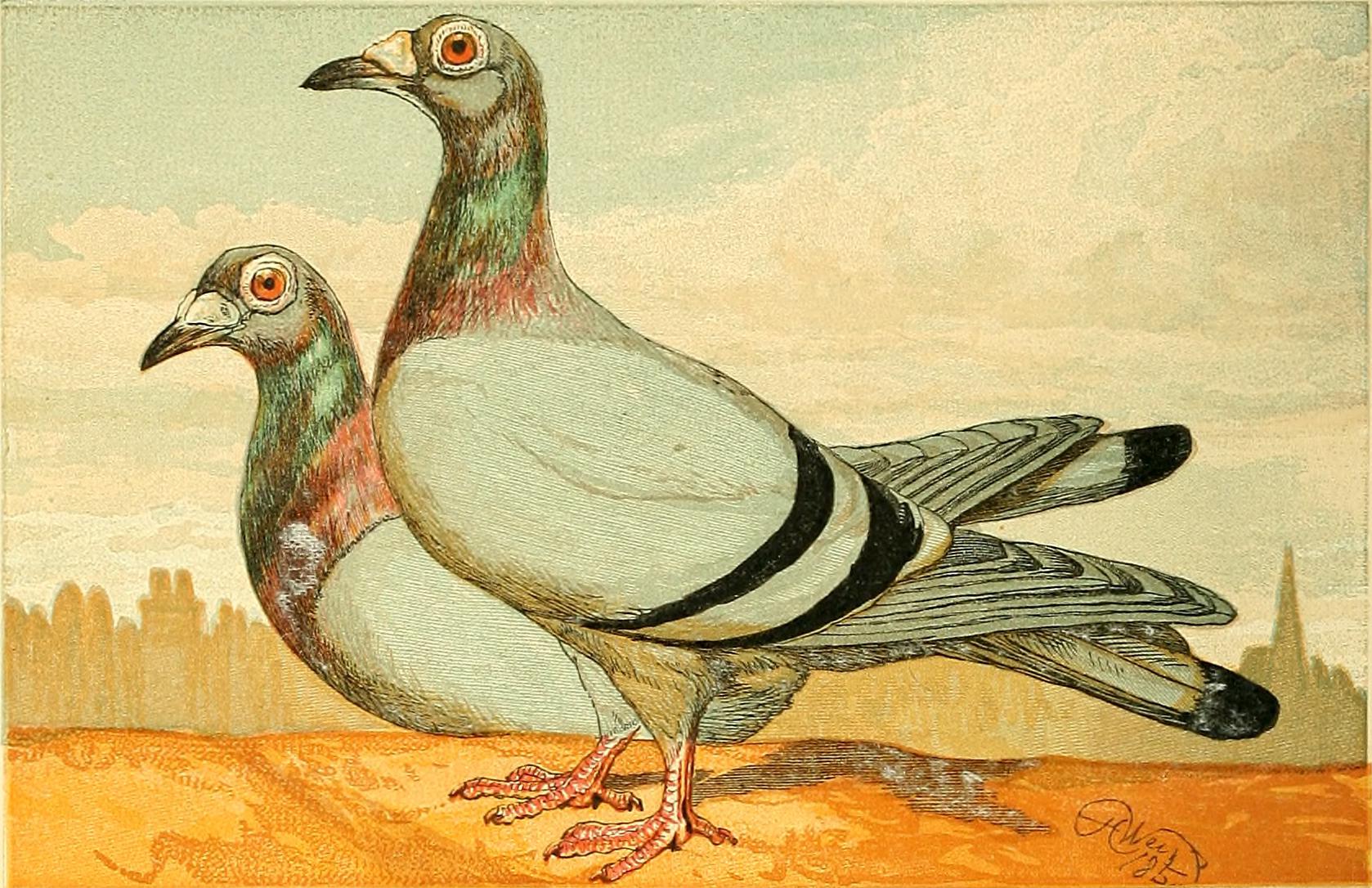

Fortunately for the garrison, pigeon racing was a popular pastime in Antwerp. Numerous pigeon clubs flourished within the city and they competed against each other at an annual competition. Fanciers even had developed a unique variety of pigeon known as the Antwerp carrier, a fusion of three breeds: the Smerle, the Cumulet, and the Dragoon. An ancestor of the modern Belgian racing homer, the Antwerp Carrier was renowned for its flight abilities and stamina. In 1819, one Antwerp pigeon flew 180 miles from London in six hours, a remarkable speed for the era. Beyond participating in sport, Antwerp Carriers had been put to commercial use; a 1824 newspaper account detailed their use in carrying stock price information from Paris to Antwerp, “ten hours earlier than any other couriers could convey them.”

Naturally, the Dutch garrison turned to pigeons to solve their communication issues. A loft was quickly erected on the site of the Citadel. By the winter of 1831, the pigeons were already delivering messages to the Citadel; a contemporaneous newspaper account observed that “a pigeon had been seen flying into the Citadel “traveling from a western direction over the Scheldt River,” bearing “important despatches to General Chassé.” At the same time, Captain Koopman, now serving as the commander of the blockade ships, entered into an agreement with two loyal Antwerp residents to establish a pigeon post that would allow the Captain to be constantly informed “of everything that might happen in rebellious Belgium.” He installed a loft in the upper room of the Flemish Head and employed a young man to catch the birds as they arrived and hand them over to him. To distribute the birds to his network of spies, Captain Koopman arranged for the pigeons to be placed in covered baskets at agreed-upon locations throughout the city. Through this method, Koopman received letters from spies out in the field as well as copies of Belgian newspapers. In a post-war memoir, he claimed information gleaned from his pigeon network prevented several assassination plots against General Chassé and himself from being carried out.

Over the next two years, the Great Powers of Europe tried to resolve the tensions brewing between Belgium and the Netherlands. They recognized Belgium as an independent kingdom on January 20, 1831, in spite of King William’s opposition. On August 2, 1831, he invaded Belgium, shortly after it had crowned its new monarch, King Leopold I. Upon the intervention of the French, however, King William agreed to an armistice, but refused to order an evacuation of the Antwerp garrison.

A whole year passed before the Great Powers acted to enforce Belgium’s sovereignty. On November 4, 1832, an Anglo-French fleet blockaded the Dutch coast, while a French army comprising 56,000 men headed toward Antwerp. On November 30th, the French army demanded Chassé’s surrender. Even though the General had only 5000 men under his command and had been informed by his superiors that no aid would be sent from the Netherlands, he refused to stand down. The French prepared for a siege by digging trenches before the Citadel. By the start of December, their guns were in place, including a new, terrifying weapon: the monster mortar, a 24-inch caliber gun. On December 4th, the French began bombarding the Citadel.

Throughout the siege, the Dutch depended heavily upon their pigeon network. Indeed, the network had recently expanded to include areas beyond the Citadel and the Flemish Head. Just before the start of the siege, “a great number of emissaries with pigeons” had been sent from the Netherlands to areas surrounding Antwerp. From Antwerp, the pigeons could send intelligence to Dutch forces in Breda and Bois-le-Duc. To combat the spread of information through pigeons, French military authorities in Antwerp required that all pigeons brought into the city have their wings clipped.

Amidst the constant bombardment, the pigeons performed their task admirably. “It is singular,” remarked a journalist covering the siege, “that, notwithstanding the noise and smoke, the pigeons employed at Antwerp as carriers were flying about in the very thick of it.” Thanks to their efforts, General Chassé received frequent updates of news from the outside and “remained in constant communication with [the] government.” Captain Koopman ,too, noted that in spite of “the incessant thunder of all kinds of artillery,” his pigeons “flew regularly to me, and brought me, among other things, daily reports of the losses suffered on the side of the enemy.” On December 13th, the Captain received a message alerting him of French plans to attack an outer defense fort. As late as December 20th, pigeons were still flying messages from the city and the Dutch flotilla to the Citadel.

Over the next two days, the French deployed the monster mortar against the Citadel with devastating effect. With much of the Citadel’s walls in ruins, General Chassé surrendered on the morning of December 23, 1832. Belgium and the Netherlands were now de facto separate states, although King William refused to officially recognize the Kingdom until 1839, following pressure from the Great Powers.

The 1832 Siege of Antwerp is the first recorded military use of pigeons in 19th century Europe. A relatively obscure conflict, it undoubtedly laid the foundation for the use of pigeons in the Franco-Prussian War nearly forty years later. It is a shame that the role of pigeons in the siege has been little studied to date.

Sources:

- “Antwerp,” The Examiner, Dec. 2, 1832, at 8.

- “Belgium,” The Vermont Gazette, Mar. 1, 1831, at 2.

- “Belgium and Holland,” The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser, Dec. 29, 1832, at 2.

- “Belgium and Holland,” The Standard, Dec. 10, 1832, at 2.

- “Bombardment and Capture of Antwerp,” Arkansas Times and Advocate, Jan. 26, 1831, at 2.

- “Carrier Pigeons,” Springfield Weekly Republican, Oct. 6, 1824, at 4.

- Claflin, Harold W., The History of Nation: Holland, Belgium, and Switzerland, at 296-303 (1906).

- Harrisburg Chronicle, Sep. 27, 1824, at 2.

- Koninklijk Nederlands Legermuseum. “Het beleg van de Citadel van Antwerpen in 1832,” (2006), available at https://web.archive.org/web/20110724160359/http://www.collectie.legermuseum.nl/sites/strategion/contents/i004551/arma17%20het%20beleg%20van%20de%20citadel%20van%20antwerpen%20in%201832.pdf

- Koopman, J.C., Zijner Majesteits Zeemagt voor Antwerpen, 1830-1832, at 38-39, 104 (1853).

- Martinet, Andre, La Seconde Intervention Française et Le Siege D’Anverse, 1832, at 237-38, 266 (1908).

- Naether, Carl, The Book of the Racing Pigeon, at 95 (1950).

- The Morning Post, Nov. 12, 1832, at 2.

- “The Siege of Antwerp in 1832”. The United Service Magazine, First Part of 1833, at 289–392.