When did the British Army first use pigeons in combat? World War One? The Boer War? The answer is the Hut Tax War of 1898, a relatively obscure colonial uprising in Sierra Leone. This week, we take a look at how the British Army, for the first time ever, relied on pigeons to communicate with a distant headquarters.

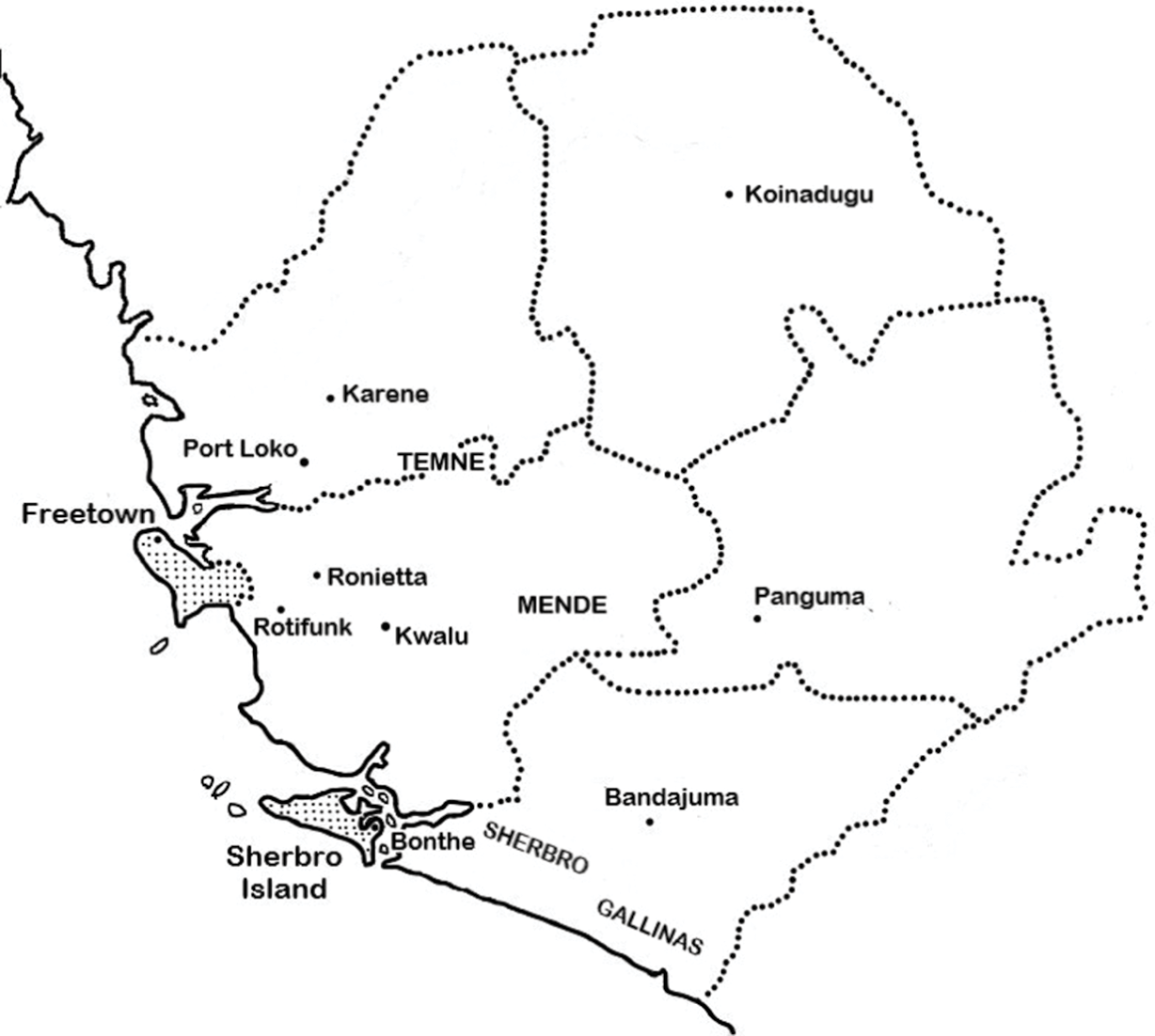

On August 31, 1896, British colonial authorities in the Crown Colony of Sierra Leone unilaterally declared the interior surrounding Freetown a Protectorate. Divided into five districts, the Protectorate encompassed numerous chiefdoms, many of which had no direct treaties or relations with the British government. To consolidate British rule over them, the colonial government issued the Protectorate Ordinance that same year, aimed at encroaching upon the chieftains’ sovereignty. The Ordinance transferred much of the chiefs’ traditional judicial powers to British District Commissioners. It undermined the internal slave trade—a primary source of income for chiefs—by granting enslaved persons the opportunity to obtain freedom by petitioning British officials in Freetown. Finally, the Ordinance implemented a tax on dwellings within three of the Protectorate’s districts, Ronietta, Bandajuma, and Karene. Dubbed the Hut Tax, it required all residents to make payments based on the size of their residence at the start of 1898.

The British also installed Frontier Police posts across the chiefdoms, composed of indigenous men led by British officers. Tasked with ensuring safe passage over roads and keeping the peace, members of the Frontier Police occasionally overstepped their jurisdiction and “interfered in local disputes,” acting as “little judges and governors.” Moreover, much of the Frontier Police had been runaway slaves who had obtained their freedom in Freetown. Chiefs bristled at the prospect of being arrested by their former slaves.

Many chiefs within the Protectorate opposed these measures, the most notable of whom was Bai Bureh. A member of the Temne ethnic group, Bai Bureh had been appointed chief of Kasseh, “a small chiefdom on the left bank of the Small Scarcies River,” in the Karene District in 1887, thanks to his military prowess. While Kasseh was a tiny chiefdom, Bureh possessed considerable authority owing to his status as a kruba or war chief. “There were very few war chiefs,” a historian has noted, “and only they possessed the right to request permission from other chiefs to travel though their chiefdoms to collect armed followers.” Karene’s District Commissioner claimed that war chiefs “were the only ones who possessed any ‘real authority’ and that one of them was worthy fifty ordinary chiefs.”

Bureh had a complicated relationship with the colonial government. He’d been arrested in 1891 for defying a British official, escaping while en route to Freetown. The next year, though, he joined in a colonial expedition against the town of Tambi. After another arrest attempt in 1894, Bureh largely ignored the British until the enactment of the Protectorate Ordinance. In 1897, he joined 24 other chiefs in submitting petitions to the Colony’s governor, Sir Frederick Cardew, protesting the Hut Tax.

Disregarding the chiefs’ opposition, colonial authorities set out to collect the tax in the Karene District in January 1898. They encountered resistance in Port Loko, “the largest and wealthiest town” in the area, and arrested the primary chief and his sub-chiefs in response. Rumors soon emerged that Bai Bureh was planning an attack on Port Loko, resulting in most of the town’s inhabitants fleeing. On February 16th, a detachment of Frontier Police set out from Port Loko to Karene to find and arrest Bai Bureh. On the road to Karene, the unit was continually harassed by Bai Bureh’s warboys, who jeered at the Frontier Police and pelted them with stones. At one point in the expedition, the parties exchanged gunfire. The Frontier Police found Karene safe, but remained concerned over the safety of the Port Loko-Karene route; most of the surrounding towns and villages had cleared out in support of the revolt.

Upon receiving word of the Frontier Police’s plight in Karene, Cardew opted for a demonstration of British power. On February 22nd, Cardew ordered a company of the 1st Battalion West India Regiment (WIR)—an Army infantry unit composed of recruits from British Caribbean colonies—to head to Karene. Commanded by Major Richard Joseph Norris, the WIR company’s primary mission was to set up a garrison at Karene, allowing the Frontier Police to pursue Bai Bureh. If necessary, the company was authorized to support the Frontier Police in case of an attack, but Cardew hoped that “once the troops arrived, resistance to the administration’s authority would collapse.”

A particular challenge facing the WIR at Karene would be maintaining contact with Freetown, which was 60 miles away. All lines of communication between Port Loko and Karene had ceased on February 19th after supporters of the rebellion stole the Frontier Police’s canoes. Cut off from Porto Loko, the Frontier Police in Karen had no way of communicating with Freetown, absent a circuitous, northwestern route. Fortunately, Thomas Chadwick, a merchant with the trading firm G.B. Ollivant and Company, came up with a solution. Having represented the firm’s interests in Freetown since 1891, Chadwick had been frustrated that “communication with the interior could be conducted only by runners.” He’d imported a loft of homing pigeons from England and trained the birds to deliver news from the interior to Freetown. The pigeons had allowed Chadwick to be “always better informed than any of his competitors regarding the position of produce stocks and merchandise requirements.” Seeing the administration was in a bind, Chadwick turned his pigeons over to the government for use in Karene.

The WIR company departed Freetown on February 25th aboard a government steamer up the Great Scarcies River and disembarked at a nearby village on the 26th. Norris and his troops marched to Karene, reaching the town unopposed on the 28th, although they were monitored by warboys. The company found the Frontier Police besieged on all sides, with three of its members in the hospital. As the situation in Karene escalated, on March 2nd, the District Commissioner requested that Norris declare martial law and assume responsibility for the administration of Port Loko and Karene, to which Norris assented. The next day, the company marched to Port Loko to restore communication between the two towns. Throughout the 25 mile march, the soldiers encountered intense opposition from Temne warboys, both sides suffering casualties. On March 4th, Norris, fearing that Port Loko would soon be attacked, released a pigeon with a message requesting two additional WIR companies from Freetown. Cardew received the message that same day, but, believing that Norris “could easily hold his own,” sent only one company.

On the evening of March 5th, the second WIR company arrived at Port Loko, only to find the town had earlier been the site of a fierce, four-and-a-half hour battle between Norris’s troops and Temne warboys. As hostilities mounted, Norris continued badgering Cardew for additional WIR companies over the ensuing days until the governor ultimately acquiesced and sent two more. Each unit departing Freetown received twelve pigeons.

By mid-March, the WIR companies had coalesced into a force of 700 troops under the command of a colonel. Now known as the Karene Expeditionary Force (KEF), the forces made Port Loko their headquarters and focused on keeping the road to Karene open. Throughout these patrols, the KEF kept Freetown apprised of developments via pigeon. “[A]uthorities at Freetown knew the position of matters at Port Loko, which is twenty-five miles off, within half-an-hour’s time,” a newspaper reported. On the evening of March 25th, a pigeon brought news to Freetown officials of a reversal suffered en route to Karene:

Things very serious; fifty of the West India Regiment and twenty-seven carriers missing; many wounded, including four officers; Lieutenant Yeld is dead.

Following an attack two days later resulting in 35 casualties and the death of the colonel from “heat apoplexy,” officers concluded that the KEF’s frequent patrols between Port Loko and Karene had resulted in excessive casualties, while the original mission of locating Bai Bureh languished.

On April 1st, the uprising took on a frenzied pace, as a new colonel, John Marshall, took command of the KEF. Under his direction, the troops set up two intermediate outposts along the Port Loko-Karene route to cut down traveling time between the towns. Marshall then implemented “a scorched earth policy in Kasseh country.” “Taking out a flying column each day,” writes one historian, “he razed every village which offered resistance to his advance.” Meanwhile, the KEF continued relying on pigeons to support its operations. “This is our daily means of communicating with the outside world,” a British medical officer noted in an April 4th letter. His letters indicate that the KEF’s pigeons kept Freetown abreast of setbacks and requests for supplies and manpower throughout the month. On April 19th, a pigeon notified Freetown that a major had been shot through the lungs while traveling between Port Loko and Karene.

For supplying pigeons to the troops, Chadwick received an official thanks and payment from the colonial government. However, it was soon revealed that Chadwick had in fact supplied some of Bai Bureh’s forces with 100 lbs gunpowder! Many merchants had actually preferred robust chiefdoms, because they could curry favor with individual chiefs. Incensed at this apparent betrayal, the Secretary of the State for Colonies Joseph Chamberlain initially pushed for the prosecution of Chadwick. But after identifying weaknesses in the case and noting that the Colony had already thanked Chadwick for his services, Chamberlain deemed it prudent to drop the matter.

Marshall’s campaign of destruction paid off—by the end of May, he reported that “[t]he whole of the disaffected areas of the Karene district had been overrun, and the power of the rebel chiefs utterly broken.” The KEF established permanent garrisons in Karene and Port Loko, while the remainder of the forces returned to Freetown on July 10th. The Frontier Police continued their pursuit of Bai Bureh, but he managed to evade capture for months until November 11th, when he was found in “swampy, thickly vegetated country.” Colonial officials spared his life, but exiled him to the Gold Coast, where he remained until he was permitted to return to Kasseh in 1905.

The Hut Tax War of 1898 soon faded from memory—it was just one of many colonial uprisings against the British Empire. But the British Army’s successful use of pigeons in the conflict remained a part of the Army’s institutional memory. During the Boer War, the Army, inspired by Sierra Leone’s example, relied on pigeons for communications during the Siege of Ladysmith in 1899 and 1900. Throughout World War I and World War II, British troops routinely employed pigeons when other mediums of communication were lacking. This long-forgotten war, therefore, merits our attention for conclusively demonstrating to British military officials that pigeons could facilitate communication under wartime conditions.

Sources:

- Abraham, Arthur. “Bai Bureh, The British, and the Hut Tax War,” The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 7, No. 1, at 99-102 (1974).

- Altham, E.A. Major, The Ladysmith Pigeon Post, The Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Vol. XLIV, No. 273, November 1900, at 1231.

- Clodfelter, Michael. Warfare and Armed Conflicts, at 210 (2017).

- Crowder, Michael, and Laray Denzer. “Bai Bureh and the Sierra Leone Hut Tax War of 1898,” Colonial West Africa, at 61-62, 64, 67, 69, 70-73, 83-88, 91-92, 94-95 (1978).

- Fyfe, Christopher, A History of Sierra Leone, at 579 (1962).

- Marshall, John. “Report, 30 August, 1898, Lt.-Col. Marshall, Commanding Karene Expeditionary Force—Operations in Timini County.” Report by Her Majesty’s Commissioner and Correspondence on the Subject of the Insurrection in the Sierra Leone Protectorate, 1898, at 613-16, 621 (1899).

- “News from West Africa,” The Standard, Apr. 13, 1898, at 3

- Pedler, Frederick, “British Planning and Private Enterprise in Colonial Africa,” Colonialism in Africa 1870-1960: Vol. 4, at 96 (1969).

- Pedler, Frederick. The Lion and the Unicorn in Africa: A History of the Origins of the United Africa Company 1787-1931, at 95-96 (1974).

- “The Disturbances in Sierra Leone,” The Times, Apr. 9, 1898, at 4.

- “The Sierra Leone Revolt,” The Birmingham Post, May 6, 1898, at 10.

- “The Troubles in Sierra Leone,” The African Review, Vol. XV, Apr. 16, 1898, at 96.

- Tobin, Richard. “A Memoir of the Late Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Dalton, R.A.M.C,” BMJ Military Health, Vol. 24, at 76-78, 1915.

- “West African Operations,” The Morning Post, Mar. 24, 1898, at 5.