Finland emerged as a latecomer to the pigeon arms race—while other countries had started supplying their militaries with pigeons in the late-1800s, it wasn’t until the 1920s that Finland implemented its own military pigeon service. This late start is unsurprising, as Finland was a possession of the Russian Empire from 1809 to 1917, known formally as the Grand Duchy of Finland. As a Russian territory, Finland lacked a separate army of its own after 1901. In the wake of the Russian revolution, however, Finland declared its independence on December 6, 1917.

A punishing civil war erupted in Finland throughout the first half of 1918, during which the nation’s newly minted military experienced multiple communication system breakdowns. In the aftermath of the war, Finnish military leaders looked abroad for ideas to bolster the military’s communications. In 1923, Major Leo Ekberg spent time in Denmark, observing his host country’s telecommunications units. He eventually was assigned to the Danish Army’s signal corps and learned of its pigeon program, becoming intimately acquainted with training techniques. Just a few months later, in the spring of 1924, Lieutenant Colonel and erstwhile trapshooter Unio Sarlin put his training for the summer Olympics on hold and traveled to Morocco for a similar mission. He was surprised to find that the Moroccan Army relied on pigeons even though radio, telephone, and telegraph equipment was readily available.

With these experiences under their belts, the Finnish officers decided it was time for their military to develop its own pigeon service. The Army obtained a small flock of pigeons for experimental purposes in 1923. The flock remained limited to just a few birds and was used on a trial basis for the next several years. In October 1927, however, the Royal Danish Army shipped 40 pigeons to Finland’s military, free of cost. Suddenly, the Army found itself with a rapidly-growing pigeon service. Sarlin assumed the mantle of leadership over the fledgling Finnish Pigeon Service (FPS). When the Danish pigeons arrived in Finland, they were assigned to a telecommunications unit in Riihimäki, which was commanded by Major Ekberg.

Ekberg possessed the requisite experience to get the FPS off the ground and it showed. The unit’s breeding program swiftly exceeded expectations; indeed, in the opening months of 1928, the military found itself with a pigeon surplus. Too many, in fact, for the Army to properly house. Although the Army had been experimenting with pigeons since at least 1923, the primary loft could hold approximately hundred birds—and that was if they were crammed in there tightly. To improve the pigeon service, Army officials contacted the Ministry of Defense and requested funds for building a larger coop. They had low expectations—such a request had been made annually since 1924, yet the Ministry never prioritized the FPS’ needs.

While the army’s petition for a bigger pigeon loft languished in limbo, FPS officers looked for places to put their birds in the interim. The White Guard, the country’s voluntary militia, expressed an interest in keeping some of the pigeons at its officers’ school in Tuulusa, while Ekberg thought that they might be useful at sites in eastern Finland, or in areas between the mainland and the outer islands to enhance coastal defense communications. The Ministry, nonetheless, ignored these proposals. Fed up with the agency’s intransigence, Ekberg told the Ministry bluntly that if it refused to build a larger coop for the military’s pigeons by 1930, then the pigeon service should be terminated, since no real support had been provided since its founding in 1923.

Ekberg’s tough tone with the Ministry worked—it quickly agreed to provide the FPS with more support. Over the next several years, the Ministry would work closely with Sarlin and Ekberg to develop a sophisticated military pigeon service. With the Ministry’s full support, the FPS once again looked abroad for inspiration. In 1930, the FPS received detailed information from their French counterparts about the French Army’s pigeon service. In 1931, FPS officials toured Germany’s pigeon stations for several weeks. The officials were awestruck at the amount of pigeon merely at the German Army’s central loft in Spandau, 1200. Encouraged by these trips, Sarlin planned further fact-finding missions to Sweden, Norway, and Estonia.

Armed with knowledge gleaned from some of the world’s preeminent military pigeon services, the FPS embarked on a series of projects. Permanent lofts were planned for military installations in Helsinki, Parola, Pori, Turku, Kangasa, Hämeenlinna, and Vyborg. FPS officials also wanted to develop improved training courses, import quality stock from Germany, and mobile lofts for use out in the field. It’s unclear from the record how many of these objectives were met.

Meanwhile, the army’s pigeon service expanded to other branches of Finland’s military. In August 1933, the Air Force received a pigeon station at the Suur-Merijoki airbase near Vyborg. The birds were to be used by pilots to communicate with the ground in lieu of radio, which still was not feasible for Finnish aircraft. That same year, the Navy received a batch of pigeons at its Maritime Defense headquarters in Helsinki. Naval officials wanted the birds for a special project: maintaining communication from submarines out at sea. Normally, a submarine could release pigeons upon surfacing, but such an option was not available to downed subs or when it was not safe to surface. To bring the pigeons from the sub to the surface, a torpedo was designed to be large enough for two military pigeons to fit inside. Ideally, upon being launched from the sub, the torpedo would rise to the surface and open up, allowing the pigeons to fly messages to the nearest naval facility. While this may seem a bit of a harebrained scheme to modern audiences, tests had demonstrated the torpedo was a safe and secure option for pigeons. Sarlin approved of these experiments, but it doesn’t appear the pigeon torpedo ever made it out of the experimental stage.

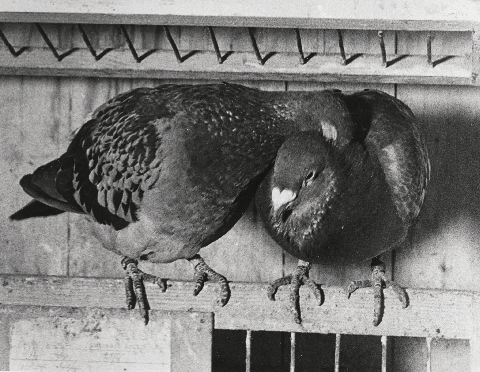

By 1935, the Finish military boasted 690 pigeons housed in lofts in Helsinki, Valkjärvi, Kiviniemi and Suur-Merijoki. These pigeons included both foreign strains and those supplied by a Finnish fancier group. As with other services, an issue frequently encountered was hawk and falcon attacks. In the fall of 1933, for example, peregrine falcons swooped in during a naval training session and killed half of the birds present. Avian tuberculosis was also a major threat, plaguing the military’s lofts. At the Kiviniemi loft, around 60 pigeons of Latvian stock were found to have tuberculosis. Other common diseases included proctitis, E. Coli, infectious rhinitis, and thrush. Finally, Finland’s extreme subarctic climate occasionally affected the birds’ performance.

In spite of the FPS’s best efforts, Finland’s military pigeon service began to lose steam in the mid-1930s, as improvements in radio technology pushed the pigeons to margins. In 1938, an internal assessment of the military’s communication sectors mentioned pigeons very little in comparison to radio units. The author recommended that the pigeons be given to the Army’s signal corps, from which they could be transported quickly to the front line by motor vehicles if necessary. Yet, when the Winter War started a year later, the birds were not incorporated into combat operations; an oversupply of Estonian field radios meant that the pigeons were no longer vital to the military’s interests. Near the end of World War II, the government slaughtered the birds and distributed the meat to injured soldiers in military hospitals. That was the death knell for the FPS—the Finnish military never worked with pigeons again.

In spite of its short existence and ignominious end, the FPS has managed to leave a footprint. The public can view exhibits dedicated to the FPS at the National Message Museum in Riihimäki and the Finnish Air Force Museum in Tikkakoski. The FPS has even inspired a modern work of fiction. Heli-Maija Heikkinen, a history lecturer and long-time admirer of the FPS, was dismayed that no stories of brave war pigeons had been preserved in the Finnish military archives. To remedy this, she wrote a novel in 2014, entitled Viestikyyhkyupseeri (The Carrier Pigeon Officer). Set during World War II, the book concerns Frans Jokimies, a pigeon trainer, breeder, and caretaker employed by the Finnish military. In September 1944, Frans receives an order from his superiors to slaughter the military’s birds. He cannot follow this unconscionable decree, so he and his wife Anja flee to Denmark with the pigeons in tow and remain there for decades. Amidst this backdrop, the author explores themes of war and sacrifice, forgiveness and relationships. It’s a worthy tribute to the FPS’ officers and pigeons and proof of their lasting legacy.

Sources:

- Karjalainen, Mikko, “Viestikyyhkyjä taivaalla,” Puolustusvoimien Kokeilutoiminta Vuosina 1918-1939, Vol. 1: 43, 2021, at 166, available at https://www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/180859/PVn_kokeilutoiminta_Karjalainen%20et%20al.%20%28verkko%29.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

- “Viestikyyhkyt Olivat Sota-Ajan Unohdettuja Sankareita.” Yle Uutiset, 27 Nov. 2014, yle.fi/a/3-7654835.

- Viestikyyhkyupseeri – Heli-Maija Heikkinen , kirja.elisa.fi/ekirja/viestikyyhkyupseeri.

- “Viestimuseo Muistaa Vainovalkeat Ja Kirjekyyhkyt.” Hämeen Sanomat, 14 June 2018, http://www.hameensanomat.fi/paikalliset/5147126.