For all practical purposes, the Great War began when Germany invaded Belgium on August 4th, 1914. Despite the valiant efforts of the Belgian Army, it was an unfair fight and the small country was quickly overrun. For the duration of the war, German military authorities occupied nearly the entire territory. This is common knowledge, yet many popular histories of the conflict neglect the German occupation of northeast France during this period. Indeed, by November, Germany had gained a foothold in ten French departments, the most populous of which was the Nord Department. This week, we take a look at four brave residents of the Nord who were executed for engaging in clandestine pigeon networks.

At the close of 1914, over 1 million French residents in the Nord Department found themselves under German occupation. Naturally, the presence of a foreign army in their homeland triggered active resistance movements, as in Belgium and Luxembourg. Espionage emerged as a powerful form of undermining German authority; Nordistes were all too eager to provide Allied secret services with enemy intelligence. While men and women bravely volunteered their services and passed on info to secret agents in person, others opted to use pigeons to send clandestine information back to the Allies. This is unsurprising—pigeon keeping was a popular pastime in the Nord region, with over 20,000 members enrolled in a regional club.

But pigeons were in short supply throughout the Nord; the German military government had ordered their destruction in October 1914 to prevent communication with the Allies. To provide Nordistes with much-needed pigeons, in March 1917, British intelligence started airdropping pigeons via balloon or plane into occupied France. Attached to a parachute, the pigeon floated down into a meadow or field, waiting for a Nordiste to find it. In the event someone found the bird, they’d notice a detailed questionnaire attached to the its leg. It was hoped that patriotic individuals would look over the questionnaire and reveal important details about German military units and movements. A set of instructions cautioned participants to disguise their handwriting and not to include their real names or addresses in case Germans intercepted the bird. This was a necessary measure, in light of French patriotism. “[T]he French people are fond of glory,” a French partisan warned a British intelligence official, “and unless they are warned, I am afraid some of them will be sticking their names to the bottom of the message just to show how they are trying to help their country.”

Getting the pigeon behind enemy lines was the simple part. Nordistes took a huge risk if they decided to use the airdropped bird for espionage. Those who had a pigeon in their possession had to be extra cautious that no one actually saw the bird. “Keeping them . . . without arousing the suspicion of the Germans or the curiosity of inquisitive neighbors, proved too great a difficulty,” British intelligence officer Henry Landau reflected in a post-war memoir of his espionage activities. If a person did send vital information, Germans might intercept the pigeon and discover his or her identity. Finally, sometimes the Germans themselves planted one of their own pigeons for unsuspecting Nordistes to find. Any info sent by that bird would end up in German lofts.

Still, those bold enough to try this venture occasionally passed on intelligence of real value to Allied officials. In May 1917, for instance, several individuals sent via pigeon the location of several ammunition depots and three big enemy guns in Cambrais. A few days later, French planes bombed the depots and two of the big guns. For this reason, German military authorities took a draconian stance against the use of pigeons for espionage. Anyone found in possession of a pigeon or identified in an intercepted despatch faced immediate arrest, followed by a trial before military tribunals. In the event of a conviction, execution by firing squad was the usual penalty.

It is in this milieu that we encounter the subjects of our story. In April 1917, a German soldier stationed in Lens, Belgium shoots down a pigeon in flight. He quickly discovers it’s a spy pigeon when he sees a filled-out questionnaire attached to its leg. In looking over the questionnaire, he realizes that an active spy ring exists in Nomain, a town in the Nord. Three names appear in the document, all residents of Nomain: Georges Rémy, a railway worker, Henri Caignet, a coal merchant, and Flore LaFrance, a young mother. The German authorities swiftly arrest these individuals and their spouses and transport them to Tournai, Belgium. An investigation into the matter implicates several other collaborators, including Georgine Bossuyt; like LaFrance, she, too, is a mother of young children.

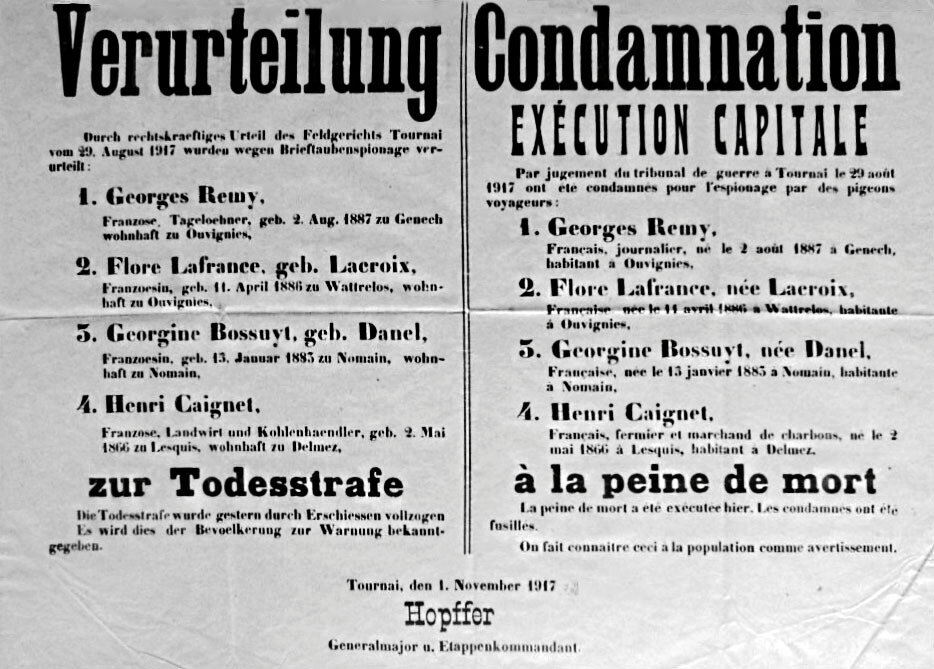

On August 4th, the accused appear before a war tribunal in Antwerp. Following the hearings, the tribunal sentences Rémy, Caignet, LaFrance, and Bossuyt to death; their spouses and other collaborators receive decade-long prison terms instead. Although the condemned file appeals of their sentences, their petition is denied in September. They’re sent back to the Tournai Citadel to await execution by firing squad. They don’t know when it will happen. In the meantime, Rémy’s wife gives birth to a daughter; she names her Georgette.

On October 31st, the collaborators are informed at 11:00 am that they will be shot at 5:00 pm. They are granted just two hours to gather with their families in a makeshift chapel and say goodbye. Eyewitness accounts paint a heart wrenching picture of these last moments. LaFrance cradles Rémy’s newborn daughter as he embraces his wife. Caignet kisses his daughter Yvonne, letting her know that he is to be shot that evening. Bossuyt bids her husband farewell, but is not allowed to see her children—they are too young and left with some of the Citadel’s nuns. An hour before the sentence is to be carried out, the families depart. A final mass for the condemned is held where they receive communion.

As five o’clock draws near, the condemned are brought to the execution site. Rémy’s legs give out and he is dragged along by two burly soldiers. Meanwhile, the women put on a brave show. Bossuyt and LaFrance—sporting cockades emblazoned with France’s national colors—vigorously refuse to be blindfolded. Each prisoner is tied to a post. The women shout “Vive La France!” for their final words. As the soldiers prepare to fire, one refuses to shoot. He is quickly replaced and the firing commences. The women are shot first and their bodies placed in coffins, but it is immediately apparent to all that Bossuyt is still breathing. She is pulled halfway out of the coffin and shot again. A priest breaks down in tears as he blesses the women’s bodies. The men are shot next without incident. The bodies are buried onsite in a mass grave before nightfall.

German authorities are confident these executions will serve as a deterrent. But they’re wrong. In spite of German threats, collaborators continue using pigeons to communicate with the Allies throughout 1917 and 1918. By war’s end, nearly 40% of the questionnaires provided by the British have returned via pigeon, beating internal estimates that only 5% would return.

The story of Nomain’s martyrs received much attention in the years following the war. Two monuments were publicly dedicated to them during the Interwar period: the Monument aux Morts in Nomain and the Monument de la caserne Ruquoy in Tournai. In the 1920s, the French government posthumously awarded each individual the Legion d’honneur, the country’s highest order of merit. Even 100 years later, their story occasionally surfaces in French and Belgian media.

This grim chapter reminds us of the harsh realities of war. In using pigeons to send confidential information to the Allies, the martyrs of Nomain took major risks and it cost them dearly—not only did they lose their lives, their children grew up without them. And yet they took these chances, motivated by a love for France that transcended self. We at Pigeons of War salute these courageous individuals for making the ultimate sacrifice to aid the Allied cause.

Sources

- Bausiers, Christian. “Les Patriotes Fusillés, Héros Méconnus.” Skyrock, 9 Feb. 2013, https://edidep.skyrock.com/3142180984-CONNAITRE-TOURNAI-SON-HISTOIRE-SES-REALISATIONS-SES-PROJETS.html.

- Connolly, James E., The Experience of Occupation in the Nord, 1914-18, at 8, 12, 15, 266-69 (2018).

- Département: 59 – Nord, https://www.memorialgenweb.org/memorial3/html/fr/resultcommune.php?idsource=30202&dpt=59

- Landau, Henry, All’s Fair: The Story of the British Secret Service Behind the German Lines, at 81 (1934).

- Thuliez, Louise, Condemned to Death, at 45-46 (1934)