Last time we looked at the Eighty Years’ War, pigeons brought hope to the Dutch city of Leiden while it was under siege by the Spanish. But not all of the Dutch rebels’ attempts at using pigeons succeeded during that conflict. The city of Haarlem fell to the Spaniards in 1573 because they learned of a relief attempt from an intercepted pigeon. This week, we look at similar events that occurred during the Siege of Zierikzee.

The failure of the Siege of Leiden showed the Spanish that the Dutch rebellion would not easily be quashed. Bearing that in mind, Spanish authorities reluctantly agreed to hold a peace conference in Breda on March 3rd, 1575. But issues of religious freedom and greater autonomy for the rebellious provinces of Holland and Zeeland proved to be a sticking point. By July, the talks had broken down, prompting the Spanish government to renew its offensive against the rebels.

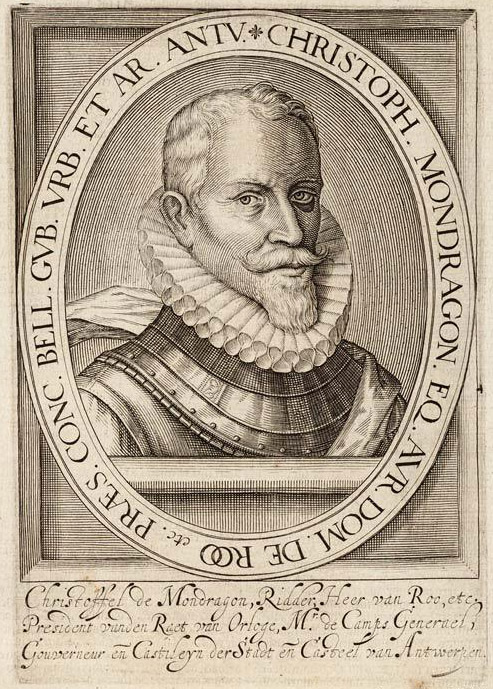

In the autumn of 1575, the Spanish forces launched a military campaign to wrest Zeeland from the rebels. Led by General Cristóbal de Mondragón, the troops invaded Duiveland Island. Meeting little resistance, most of the island quickly fell under Spanish control. They turned their attention westward to Schouwen Island. The most important town in that area, Zierikzee, was offered favorable terms for surrender by Mondragón in September. While the city’s council leaned toward accepting the offer, a letter from Prince William of Orange implored them to hold out for two or three months until he could bring reinforcements. Eventually, by the end of October, the town’s officials came around and rejected the surrender offer. Mondragón immediately surrounded Zierikzee with troops and artillery. The siege had begun.

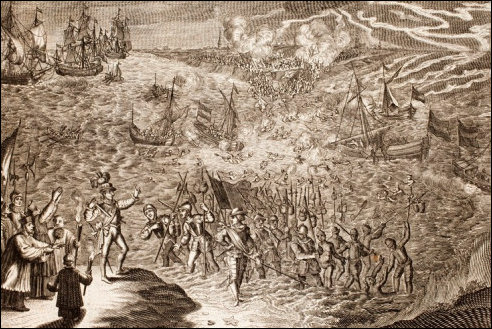

For seven months, Spanish forces assaulted the city. All roads to Zierikzee were closed off, making it impossible for the city to be supplied by land. The city could still be reached by its harbor at first, allowing the Prince to supply Zierikzee with provisions and weapons. A blockade of the harbor in January 1576, however, put an end to that. A rebel flotilla tried to break through in April. Although a few Spanish ships were captured and another was set aflame, the Spanish successfully pushed back the rebels’ ships. By May, the town had to impose rationing as provisions dwindled. To keep in touch with the Prince, inhabitants tried to smuggle pigeons to the rebel ships stationed near Walcheren Island. This was no easy feat—a smuggler had to swim past the Spanish ships surrounding the island and make it over the rebel ships. On April 21st, two men tied pigeons around their necks and swam toward the rebel ships, only to be caught by the Spanish.

In spite of the perils, several pigeons eventually were smuggled to the Prince. On May 18th, the Prince, along with Admiral Louis de Boisot—the hero of Leiden’s relief—prepared a message detailing their plan to attack the Spanish blockade with Boisot’s ships on May 27th. The note was tied to the bird’s leg and it was released. Unfortunately, the Spanish shot the pigeon as it was flying towards Zierikzee. Mondragón found the plans for the relief and sent them to his superiors, along with a feather from the bird. Thus, as Boisot’s ships reached Schouwen Island on May 27th, they encountered fierce resistance from the Spanish. Boisot’s flagship was sunk, killing him and many others. The remaining rebel ships quickly departed.

The Prince, never one to slink away from a challenge, sent another letter to Zierikzee via pigeon. He explained that he had 2000 “fine and skilled” Scottish soldiers ready to participate in a relief effort in mid-June. However, a Spanish musketeer shot this bird, too, as it flew toward the city. Aware that the Spanish government had possession of the Prince’s plans, the city finally threw in the towel and surrendered. On June 20th, city officials entered into negotiations with the Spanish, which concluded on July 29th. Spanish troops entered Zierikzee and took possession of the city, but, fortunately, the occupation was not long lasting. Fed up with a lack of pay, Spanish troops mutinied on July 12th. They squeezed the city’s inhabitants for money and goods, then abandoned the occupation on November 3rd.

The Siege of Zierikzee is a reminder that pigeons are not always a foolproof medium of communication. A bird can fail to deliver an important message, or, even worse, that message might be intercepted by hostile forces. These risks must be borne, however, in circumstances where suitable alternatives are not readily available.

Sources:

- De Zierikzeesche vrijheidsdag, at 44-45 (1872).

- Kanter, Johan de, Chronijk van Zierikzee, at 147 (1794).

- Swart, K.W., William of Orange and the Revolt of the Netherlands, 1572-84, (2003).

- van Riemsdijk, A. W. G., Secundum Fidem et Religionem: Philibert van Serooskerke (1537-1579) Een Zeeuw in dienst van de Spaanse koning. nvt (2021).