Many of the pigeons that participated in the Great War received names related to the conflict. The first American pigeon to deliver a message from the trenches was named Gunpowder, while British soldiers called one prominent bird Dreadnought. It should not come as a surprise, then, to learn that at least two pigeon heroes of the War were nicknamed the Poilu. A term of endearment for French infantrymen, the word literally means “The Hairy One,” a reference to the soldiers’ mustaches. In the case of the pigeons, however, the name seems to have alluded to their red-checkered coats, as the feathers resembled the traditional red trousers worn by the French soldiers.

The first Poilu achieved renown during the Battles of Yser and Aisne in the opening months of the War. Details about his service are lacking, but evidently it was impressive—Marshal Ferdinand Foch awarded the bird the Croix du Guerre. The citation for his award reads as follows:

On four occasions during the Yser and Aisne battles this carrier pigeon assured the rapid transport of important messages under heavy fire without error.

The Poilu lived until 1927. As a final honor, his body was stuffed and donated to the 8th Engineers Regiment, the Army unit responsible for France’s pigeons. The Regiment opted to display the Poilu in the hall of its headquarters in Montoire, France.

The second Poilu of fame was hatched in an American loft in France in the final year of the War. Like President Wilson, the Poilu first saw combat in mid-September 1918, when he was selected to accompany Lieutenant-Colonel George S. Patton’s Tank Battalions as they rode to the Saint-Mihiel salient. Carrying a total of 202 birds into action, the Tank Battalions lost only 24 of them in the process, mainly a result of inexperienced handling. By all accounts, the Poilu performed “splendid work” for the tanks, flying messages from the battlefield to American officials stationed at Ourches-sur-Meuse.

As American troops withdrew from Saint-Mihiel, the Poilu was transferred to the Meuse-Argonne sector and assigned to the lofts at Cuisy. Before his training began, Captain Jack Carney, a Signal Corps officer who helped establish the American Pigeon Service, examined the Poilu and other birds in the loft. He reported the following exchange with the bird’s trainer in a post-war account:

‘Do you think he will go the route, Van Herwarden?,’ I asked the loft trainer.

‘I know it, sir. He went through St. Mihiel with the tanks. That’s the Poilu, sir. They don’t breed them any better. He’ll do all that’s asked of him, sir,’ was the quiet reply.

The trainer’s confidence in the bird was well placed. While out in the field on November 7th, an eagle-eyed officer spotted a German ammunition train and wanted to send word of this to HQ. Aware of his sterling reputation, he chose the Poilu for the task. As the bird flew back to Cuisy, he was hit by shrapnel multiple times, but kept flying. “With flesh and feathers on his head and neck hanging in ribbons, and reeling like a drunken man,” the Poilu landed in his loft with the message intact. The despatch was delivered to an artillery unit, which made short work of the ammunition train.

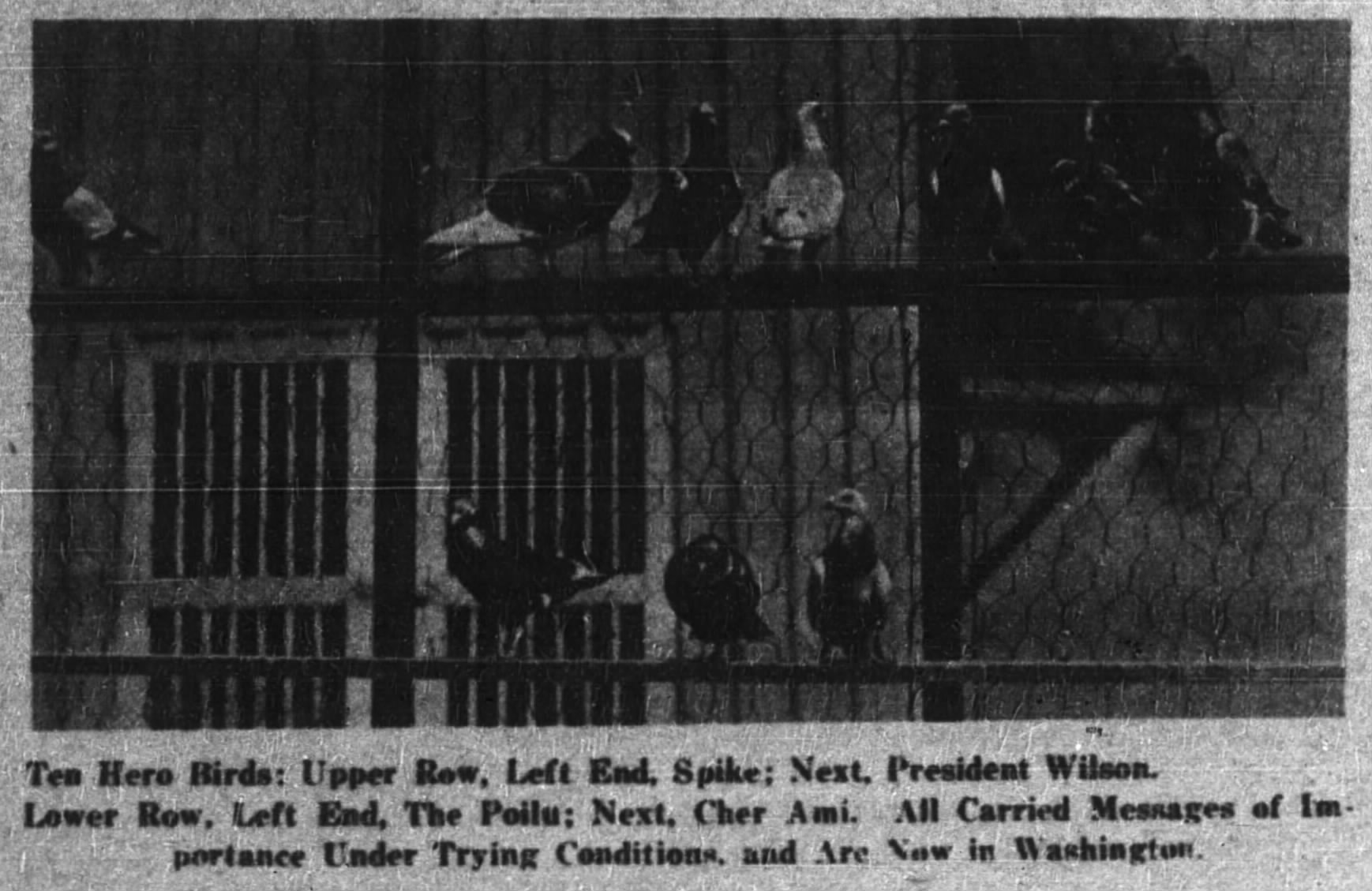

The Poilu received acclaim within the Signal Corps for achievements. Seeing an opportunity to create a public interest in the Army’s pigeons, General John J. Pershing issued an order requesting that the Poilu and other special war pigeons be sent to the United States for public exhibition. The Poilu boarded the troop transport ship Ohioan and arrived in Hoboken, New Jersey on April 16th, 1919. He was sent to a special Army loft for distinguished military pigeons in Potomac Park in Washington, D.C., where he joined President Wilson, Cher Ami, and around 20 other pigeons. Open to the public, the loft allowed the pigeons to live a life of ease—food was provided and they were not expected to work, aside from daily flight exercises. Not much information is available about the Poilu’s life afterwards. Presumably, he either was given away to a zoo or a private collector, or remained in the Signal Corps as a breeding bird.

The Poilu—the bearded French soldier, that is—was applauded in propaganda and war memorials for his bravery and endurance. We at Pigeons of War believe that those qualities were also present in the feathered Poilus.

Sources

- Blazich, Frank A. “Feathers of Honor: U.S. Army Signal Corps Pigeon Service in World War I, 1917–1918.” Army History, No. 117 at 45-47.

- Bryant, H. E. C., “Pigeon Heroes to Be Honored,” The Charlotte Observer, Apr. 16, 1919, at 9.

- Carney, Jack, “Story of Cher Ami’s Flight, Wounded, with Vital Message, Related by Captain Carney,” The Pittsburgh Daily Post, Apr. 27, 1919, at 1, 11.

- “Crippled Pigeon May Be Awarded D.S.C.,” The Evening Star, Apr. 17, 1919, at 2

- “France Honors War Pigeon,” The Springfield Leader and Press, May 30, 1927, at 9.

- Macalaster, Elizabeth, War Pigeons: Winged Couriers in the U.S. Military, 1878 – 1957, (2020).

- Naether, Carl A., The Book of the Racing Pigeon, at 59 (1944).