Since the Siege of Paris (1870-71), armies have tried to neutralize military pigeons. The reasons for this are easy to understand—pigeons allow the enemy to request aid and to receive confidential information from spies. To put a stop to these birds, militaries have recruited sharpshooters and hawks to dispatch them, or released intercepted pigeons with deceptive messages. This week, we examine these efforts in detail.

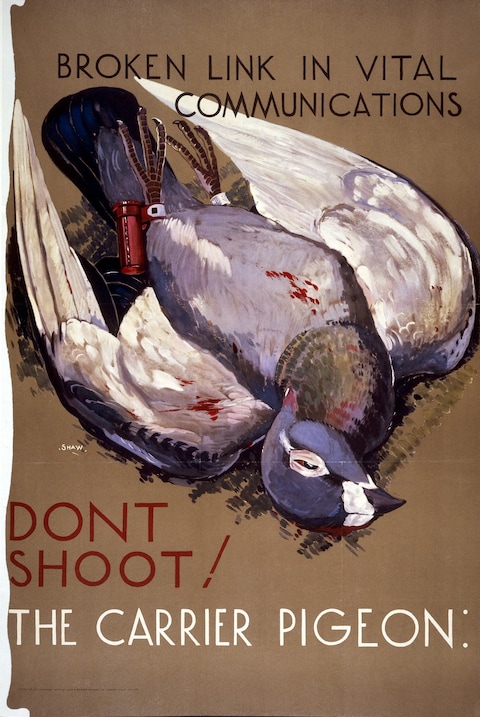

The most effective way to sabotage a military pigeon is perhaps the simplest—shooting the bird before it reaches its destination. Pigeons aren’t exactly hard to see—their bright patches of white or colored feathers and distinctive outlines make them easy targets. A shotgun is ideal for this purpose. Throughout the Great War, both the Allies and Germans were equipped with shotguns for shooting pigeons. Indeed, during the Battle of Verdun, the German Crown Prince Wilhelm formed a crack battalion of experienced trapshooters and equipped them with shotguns to shoot down any pigeons spotted flying to French HQ. During World War II, the Germans stationed marksmen along the northern French coast to shoot down pigeons flying toward Britain. In the leadup to the 1944 Invasion of Normandy, for instance, sharpshooters in Germany’s 352nd Division killed 27 Allied birds over two months.

But shooting pigeons mid-flight is not as easy as it seems, especially if the birds are released in groups. It also diverts soldiers from other duties and wastes ammunition. For these reasons, armies have experimented with training hawks and falcons to attack pigeons—a tactic that dates back to the Franco-Prussian War. When Prussian soldiers encircled Paris in 1870, the Parisians had collected some 800 pigeons from the north of France in advance of the siege, allowing them to send out information about the city to outer regions. Prussian troops released peregrine falcons to attack these pigeons as they flew from the city. To throw the falcons off, Parisians began releasing several pigeons “in rapid succession, each carrying a false note, until all of the enemy’s falcons were flying through the air in pursuit of one or more of the birds.” With a suitable distraction in place, a pigeon with an important message would be turned loose, escaping unscathed.

As armies eagerly added homers to their ranks during the Great War, rumors surfaced that the Germans had trained hawks and falcons to kill pigeons. By the Second World War, both the Allied and Axis Powers had incorporated birds of prey into their armies. The English Channel and North Sea were the scenes of most of these aerial battles. The Germans unleashed their falcons along the coast from Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, killing scores of pigeons. Likewise, the British, fearing German spies were using pigeons to contact their superiors, deployed falcons in the Channel Islands and coastal towns, but with much less success—a post-war report indicated that the British falcons hadn’t brought down a single enemy pigeon.

Birds of prey aren’t an entirely foolproof strategy—a hawk cannot be trained to distinguish between enemy and friendly pigeons. A soldier doesn’t have to kill a military pigeon to sabotage its mission, though. If the bird can be intercepted, one may insert a fake message into its message holder and release it. This technique has its roots in the Siege of Paris (1870-71). At one point during the siege, a French agent was caught traveling to Tours with Parisian pigeons. The Prussians took his six birds and released them with dubious messages. Parisian officials, nonetheless, saw through the ruse when the birds arrived “on account of the manner in which the messages were attached, and of the signatures appended.”

During both World Wars, both sides occasionally came across enemy pigeons, often when they captured soldiers or intelligence agents carrying them. While some of these birds were kept for breeding purposes (or eaten), others were roped into counterintelligence work. In the Great War, a British soldier who had been a medal maker learned to perfectly imitate the distinctive German message holders, which were “splendidly finished . . . with a red seal at the top.” Intercepted pigeons thereafter brought many dud messages back to the Germans. In his memoir on his unit’s experiences fighting the Germans in Italy in 1943-44, American pigeoneer Gordon Hayes reported that the Germans frequently attached to captured pigeons “a false message with a deceptive overlay map urging us to fire or bomb a certain location, seemingly the center of a heavy concentration of their troops and supplies. In fact, the false target would turn out to be a center of American troops or supplies.”

A special instance of counterintelligence involving pigeons emerged during the British campaign to airdrop homers into German-occupied territory to aid the resistance. It was hoped that members of the resistance would find these birds and send messages back to the British mainland. German forces, however, often found the birds. Sometimes the Germans attached a message requesting the names of resistance members or drops at suspicious locations. British intelligence sussed out many of these fake messages because the Germans tended to put too much military detail in them, revealing information that an average civilian would not know. Other times, the Germans swapped out the British bird with a German one, allowing for sensitive information to show up in German lofts. Aside from undermining British intelligence efforts, these acts also discouraged resistance members from participating—once word got out about this, the returns from British airdrops in the Netherlands dropped to zero for some time.

In lieu of counterintelligence work, there is a simpler option available for detained pigeons—a soldier can send a nasty message to the enemy. A steady barrage of demoralizing despatches can seriously damage the spirits of a platoon. And it doesn’t require much creativity or scheming. As recollected by Hayes, the 36th Infantry Division received the following dispiriting messages over a four-day period:

Monday, January 24, 1944

To the Americans

36th Division

Here is your pidgeon back. The German troops have enough meat to eat. By the way, we are gladly looking forward to your next visit by your degenerate lice-infested comrades.

(Signed) The German Troops

Tuesday, January 25, 1944

To the Americans

36th Division

We have your poor night patrolmen. Here is your pidgeon #2 back, so you will not have to starve. What do you want with your tin can tanks? Your imprisoned syphilitic comrades showed us the worth of the American soldier. We had to kill some of them before imprisonment. Right now your divisions south of Rome got hit. You sad nose-diggers.

(Signed) The German Troops

Friday, January 28, 1944

To the Americans

36th Division

Herewith we return a pidgeon to you. Your officers are too stupid to destroy important documents before being captured. At the present moment your division in the southern sector is getting a good hitting.

You poor fools.

(Signed) The German Troops

Hayes noted that his unit received similar messages throughout the War, but that they were too foul to print.

As the above demonstrates, there are abundant options available for compromising a military pigeon’s mission. Killing a pigeon prevents hostile forces from delivering vital information, while releasing a captured bird with erroneous information undermines intelligence gathering. The method utilized ultimately depends upon the needs and goals of the troops.

Sources:

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 113-114 (1888).

- Balkoski, Joseph, Beyond the Beachhead: The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy, at 78 (1989).

- Corera, Gordon, Operation Columba: The Secret Pigeon Service, 95-96, 106-106, 252-254 (2018).

- “Demobilization of War Pigeons,” The Decatur Daily Review, May 28, 1919, at 1.

- Gladstone, Hugh, Birds and the War, at 11-12 (1919).

- Hayes, Gordon H., The Pigeons That Went to War, at 66 (1981).

- “They Winged Their Way Through Skies of Steel,” The American Legion Weekly, Vol. 1, No. 9, Aug. 29, 1919, at 16-18.

- Walsh, George E, “Homing Pigeons,” The Southern Bivouac, Vol. 11, No. 1, June 1886 , at 187.