A lot of ink has been spilled about military pigeons and their heroic actions during wartime. But what about those in peacetime armies? This blog is part of an occasional series examining military pigeon services in countries with strong traditions of neutrality. This week, we look at Sweden’s former military pigeon service.

Like most European countries, Sweden’s use of military pigeons dates back to the latter-half of the 19th Century. In the fall of 1886, the Swedish Army decided to establish a pigeon service at the Karlsborg Fortress. Situated on the Vanäs peninsula by lake Vättern, the Fortress was built to realize the Army’s central defense idea, a concept in vogue following the Finnish and Napoleonic Wars. In the event of war, the King and his government would retreat to the secluded Fortress to carry out their official functions. A pigeon service was highly desirable under these circumstances, as it would allow the government to communicate with the surrounding terrain without the need for telegraph lines.

Lieutenant Berggren, an officer in the Royal Fortifications Corps, was tasked with setting up the loft at Karlsborg. He traveled to Copenhagen, Denmark to brush up on his pigeon knowledge. While there, he purchased several hundred birds from a wholesaler. Once the loft was established, Berggren turned over day-to-day management to an engineering unit.

To ensure reliable service over a wide expanse, soldiers focused on training the pigeons to fly from specific areas—Örebro in the north, Bråviken in the southwest, and Tibro and Stenstorp in the southeast. Impressive results were obtained when conditions were optimal. At Bråviken, the birds flew 84 miles (135 km) within 2.5 hours. In Tibro—around 17 miles (27 km) away from the Fortress—the pigeons arrived back at their loft within 15 minutes. However, a release at Stenstorp during wind and rain resulted in the pigeons not returning until days later. Hawks also preyed on the flocks from time-to-time. At some point in the 1890s, the loft was discontinued.

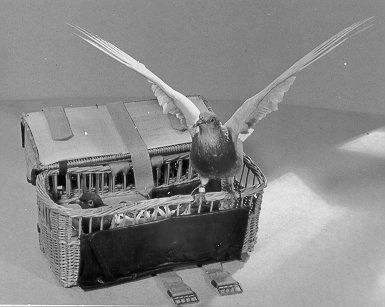

The military did not consider using pigeons again until 1909, when a special committee proposed that a “balloon and pigeon department” be established at the Boden Fortress. Presumably, the pigeons would’ve allowed the balloon pilots to communicate with their home base while in flight. However, it doesn appear that this suggestion was ever acted upon, as it wasn’t until the 1920s that the Swedish military re-established its pigeon service. Inspired by the success of other countries’ pigeon services during the Great War, the country’s navy experimented with pigeons at its air station in Rindön and at the Gothenburg naval depot, seeking to use the birds in lieu of radio for reporting accidents or observations. The Army, too, brought back its pigeons, setting up lofts at Boden and Stockholm and experimenting with mobile coops stationed throughout the country. The Army also worked toward developing a breed of pigeon acclimatized to the climate in Upper Norrland, the country’s northernmost region.

Aware of increasing international tensions, in 1936 the Swedish government increased the budget for its military. One result of this was that the Army reorganized its pigeon service, placing it under the Signal Troop’s control. With Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1st, 1939, Sweden officially declared its neutrality. Nevertheless, the Soviet Union’s invasion of Finland on November 30th, followed by Germany’s invasion of Denmark on April 9th, 1940, prompted the government to implement general mobilization. From 1939 to 1945, around 1 million Swedish conscripts were drafted for military service.

During this period of military preparedness, the Signal Troop’s pigeon service was fully involved in Army operations. A summary of the service’s activities during this time can be found in the memoir of Per Gunnar Bengtson, who was drafted into the pigeon service in 1939. In April 1940, fearing a German invasion from the south, the Army moved most of its pigeons and mobile coops to Skåne County. While there, Bengtson trained his birds to make flights from the County’s coasts. As the threat of invasion dissipated, pigeon units—including Bengtson’s—were then sent to other parts within the country, such as Västra Götaland County. The units trained their birds for scouting and reconnaissance missions, as radio communications were not well developed at that time. That winter, military officials encouraged the pigeon units to conduct cold weather experiments to see if using pigeons in winter conditions was possible. In one experiment involving 30 of Bengtson’s pigeons, only 4 were lost over 21 winter flights. Although many of these pigeons did not return to their lofts in a timely fashion, these results were nonetheless encouraging, given that some flights had occurred during

In the spring of 1941, Bengtson’s unit and several others were sent to Dalarna County near Norway and directed to train their birds to make flights from the border. In spite of vast forests and abundant birds of prey, Bengtson’s pigeons obtained some of their best results in this area. Cooperation with the local infantry units was also excellent—the pigeons were sent to posts at various defense lines and even participated in a larger battalion exercise. Good results were also achieved in Jämtland County that summer, though pigeon losses were greater owing to the mountainous terrain. By spring 1943, Bengtson’s unit found itself in Värmland County, but further from the border. Training now focused on longer flights. Because of a lack of gasoline, all of the pigeons now had to be transported to training sites via bicycle. In spite of these challenges, Bengtson’s unit did not lose a single bird in this period. Shortly thereafter, Bengtson’s unit was demobilized, as the Army wound down its affairs once it became apparent Germany no longer posed a threat to Sweden.

In spite of promising results attained during Sweden’s military preparedness campaign, the Army’s pigeon service would not be around for much longer. In 1948, Army officials recommended that the service be disbanded as a cost-cutting measure. Rather than using their own birds, officials proposed that the Army could rely on civilian fanciers to supply pigeons, if the need arose. To support this endeavor, they also suggested that the state issue annual grants of 7,000 krona to the Swedish Carrier Pigeon Association—this amount would support the group’s activities and entice members living near strategic military sites to supply pigeons to the Army as needed. The government adopted the Army’s recommendation and the pigeon service was officially dissolved in 1949.

Sweden’s military pigeon service forms an interesting chapter in the country’s military history. Although the birds were never tested in combat, they improved communications within the Swedish military when reliable radio service was lacking. We at Pigeons of War think that is worthy of praise.

Sources:

- Angående Statsverkets Tillstånd Och Behov Underbudgetåret 1928/1929, available at https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/proposition/angaende-statsverkets-tillstand-och-behov_DP301b1

- Ballonghallen. Fortifikationsverket.. Retrieved September 8, 2022, from https://www.fortifikationsverket.se/fastighetsforvaltning/fastighetsbestand/byggnader/1910-1930-talet/ballonghallen/

- Bengtson, Per Gunnar, Brevduvan i Militär Tjänst, (1984)

- Betänkande och förslag rörande revision av Sveriges försvarsväsende – Del 2 – Sjöförsvaret – Sammanfattning av revisionens förslag – Särskilda yttranden, at 20 (1923).

- Kungl. Maj:ts proposition nr 206, available at https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/proposition/kungl-majts-proposition-nr-206_E930206b1/html

- Rundgren, K. G., Brevduvan. En kulturhistorisk studie, at 123 (1991), available at https://www.postmuseum.se/bocker/1991/1991_9-111-126_Rundgren.pdf

- Högman, H, Animals in War Service. Military. Retrieved September 7, 2022, from http://www.hhogman.se/animals-in-war-service.htm

- Högman, H, Sweden’s Military Preparedness 1939 – 1945. Military. Retrieved September 8, 2022, from http://www.hhogman.se/infantry-swe-1939-1945.htm