A European city encircled by enemy forces. The inhabitants—cut off from food and communication with the outside world for months—recruit pigeons to fly messages into the city.

Sound familiar? Readers of this blog will undoubtedly be reminded of the 1870-71 Siege of Paris, but this scenario has happened several times in European history. This week, we take a look at how pigeons brought relief to the Dutch city of Leiden in 1574 during the Eighty Years’ War.

In the latter-half of the 16th century, the Dutch populations of the Habsburg Netherlands began rebelling against the reign of King Philip II of Spain, motivated by myriad issues. Led by the charismatic William the Silent, Prince of Orange, many of the cities in Holland and Zeeland revolted, with the city of Leiden joining the fight in 1572. Spanish forces tried to retake these wayward cities via siege warfare, but achieved mixed results. Haarlem fell to the Spanish in July 1573, while Alkmaar repulsed a siege attempt in October. That same month, Spanish General Francisco de Valdés launched a siege against Leiden. The blockade lasted until April 1574, with the Spanish making no progress against the city’s defenses. The siege was halted while de Valdés squared off against invading rebel troops.

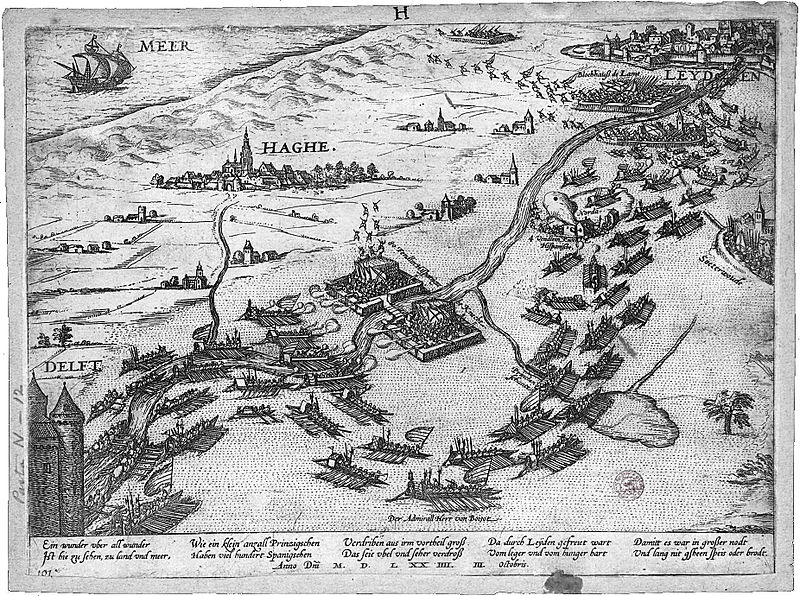

On May 26, 1574, de Valdés and his troops returned to Leiden, setting up sixty-two fortified positions blocking every road in and out of the city. The Prince of Orange circulated a letter to the city officials, pleading with them to hold off for at least three months; he needed time to cut the nearby dikes and let the North Sea flood the area, allowing the rebel flotilla to sail in with reinforcements and provisions. Residents buckled down for a tough summer.

Although the siege had been halted for a few weeks, the city had failed to replenish its food stores—there was only enough to last for two months. By August, the bread had run out. Desperation set in—the inhabitants ate anything and everything they could get their hands on, including dogs, cats, and rats. Beer, too, was in short supply, forcing people to drink foul canal water. To make matters worse, plague and dysentery swept across the area. A total of 6,000 citizens died, nearly half of the city’s 15,000 population.

As August gave way to September, the situation seemed utterly hopeless. Beaten down by hunger and disease, many townspeople felt the time had come to surrender to the Spanish, knowing full well there was a chance that the troops might slaughter everyone in the city. On September 8th, a riotous crowd gathered outside of the town hall to demand Leiden’s surrender. In a dramatic gesture, Mayor Pieter Adriaansz van der Werf announced to the group that the city would never surrender and allegedly offered to let the starving population eat his body. Inspired by his noble offer, the crowd dropped their demands and dispersed.

But symbolic acts would only keep Leideners mollified for so long. City officials needed to get in touch with military leaders to find out if aid was forthcoming. Couriers were not an option, as it had grown too dangerous for them to travel back-and-forth through the enemy lines. Officials considered the possibility of using pigeons. During the Siege of Haarlem, the city had used them to communicate with the Prince of Orange. A pigeon post was not without its hazards, however. Indeed, one of the birds sent by the Prince to Haarlem had fallen into the enemy’s hands, revealing his plans to the Spanish. Alerted to this new medium, Spanish soldiers thereafter shot every single bird that flew over their camps. Officials also wondered if there were even any pigeons left in a city wracked by starvation.

Thankfully, Willem Cornelisz. Speelman, a church organist, stepped up to the plate. Somehow, Speelman and his brothers had kept eight pigeons alive during the famine—a remarkable testament to their willpower. Speelman turned the birds over to city officials, who arranged for them to be smuggled past the Spanish camps. On September 26th, two men from Leiden reached the rebel fleet and told them about their dire circumstances. They handed the pigeons over to Louis de Bosiot, the commander of the fleet, who wrote two letters detailing his progress—he assured city officials that his ships would sail into Leiden as soon as the waters were high enough to pass through the now-broken dikes.

On September 28th and 29th, two of Speelman’s pigeons returned bearing de Boisot’s messages. The letters were read in public and bells were rung. Leideners rejoiced at the news that relief was imminent. They didn’t have to wait much longer. On October 1st, a major storm caused the North Sea to flow through the broken dikes, flooding the land near Leiden. Fearing the incoming floods, de Valdés and his soldiers hurriedly abandoned the siege on October 2nd. The next day, the rebel fleet arrived at Leiden, distributing bread and herring to the city’s population. The city had been saved from the brink of destruction.

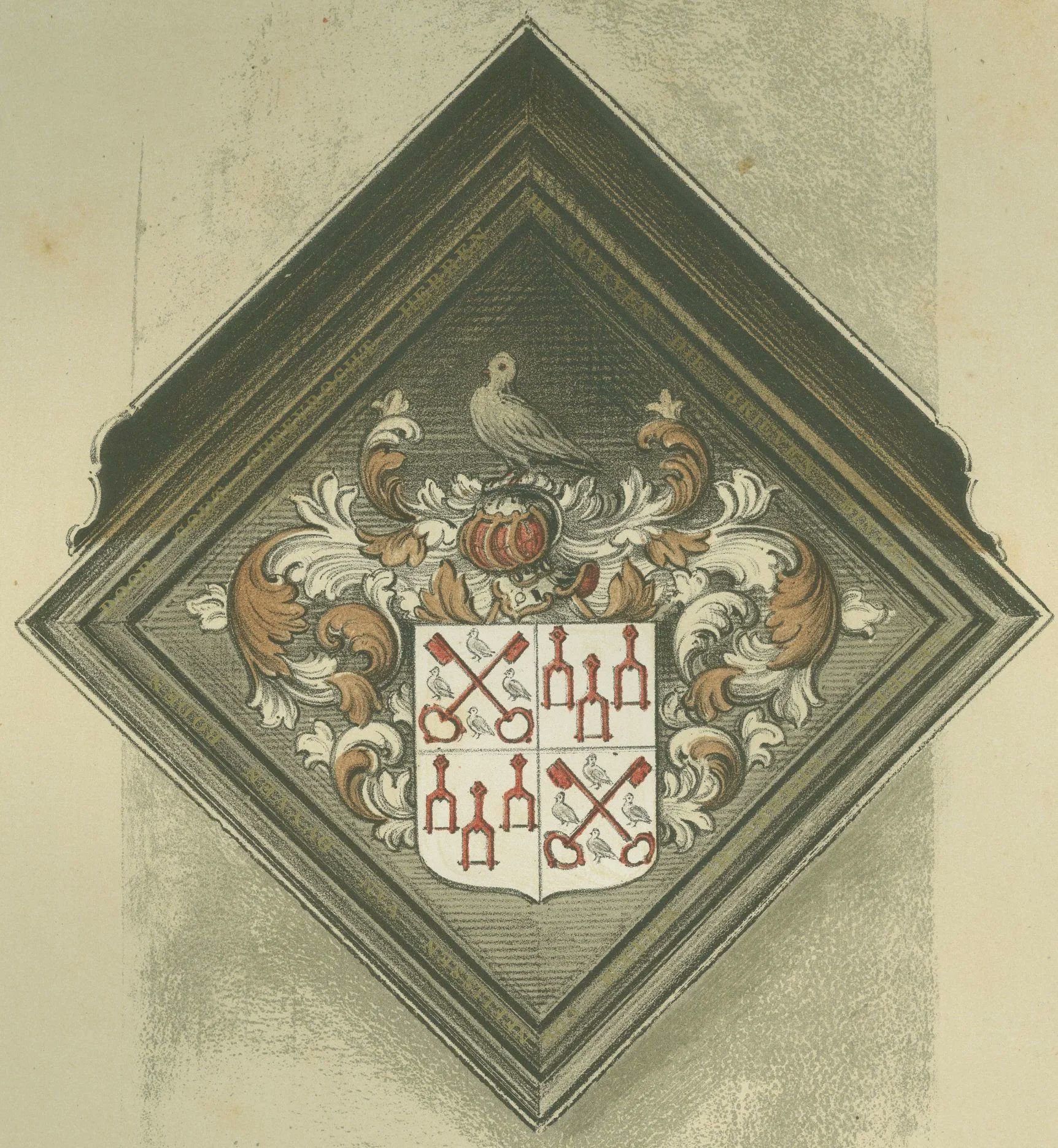

Thanks to his efforts, Speelman became a town hero. His pigeons had brought assurances to Leideners that help was on the way. Had this news not arrived, Leiden might have surrendered, dissuading other cities from revolting. Speelman received a gold medal in 1578 in recognition of his contributions as well as the honorific surname Van Duivenbode (the Pigeon Messenger). His family also received the right to bear a coat of arms featuring two red keys of the city and a blue dove in each of the four quadrants—a privilege rarely accorded to non-nobility.

The pigeons, as the bearers of good tidings, were likewise lauded for their efforts. The city paid for their food for the remainder of their lives. After they died, they were stuffed and mounted for display in Leiden’s town hall. A popular exhibit for several centuries, the pigeons were eventually lost to the ravages of time. The letters they carried from de Boisot have survived—they can be seen at the Museum de Lakenhal.

Each year, Leiden commemorates its salvation with lavish celebrations on October 3rd. Residents eat bread and herring while participating in parades, historical reenactments, and memorial services. We at Pigeons of War plan on raising a glass that day to Speelman and his pigeons, who brought Leideners hope when it was most needed.

Sources:

- Albert, Marvin H., Broadsides & Boarders, at 25 (1957).

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 112 (1888).

- Clarke, Carter W. “Signal Corps Pigeons.” The Military Engineer, vol. 25, no. 140, 1933, pp. 133–38. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44563742. Accessed 30 Aug. 2022.

- Ekkert, R.E.O, Jaarboekje 1974 voor geschiedenis en oudheidkunde van Leiden en omstreken, at 11, 197-215 (1974).

- Joel, Lucas. “Benchmarks: October 2, 1574: Dutch Unleash the Ocean as a Weapon of War.” Earth: The Science Behind the Headlines, 20 Sept. 2016, https://www.earthmagazine.org/article/benchmarks-october-2-1574-dutch-unleash-ocean-weapon-war/.

- Koppenol, Johan, “Noah’s Ark Disembarked in Holland: Animals in Dutch Poetry, 1500-1700,” Early Modern Zoology, Vol. I, at 478 (2007).

- Mackeson, Charles, “Sketches of Travel in Holland,” The Churchman’s Shilling Magazine and Family Treasury, Vol. XXX, Sept. 1881 – Feb. 1882, at 520.

- “Siege and Relief of Leiden.” Museum De Lakenhal, https://www.lakenhal.nl/en/story/siege-and-relief-of-leiden-oud.

One response to “Pigeons in the Eighty Years’ War: The Siege of Leiden (1574-75 A.D.)”

[…] under siege have resorted to pigeons for communicating with the outside world—the sieges of Leiden (1574-75) and Paris (1870-71) are prominent examples. At Mutina, as in Leiden and Paris, the pigeons seem […]

LikeLike