A declaration of war is often accompanied by economic opportunities. Governments invest heavily in industry to meet demand and fortune often follows those lucky enough to get a contract. But not in every case. Today, we discuss the plight of August De Corte, a pigeon fancier-cum-inventor who advised the United States Army Signal Corps during World War One. Despite supplying the Corps with pigeons and developing wartime equipment, De Corte ultimately was left impoverished after the War.

Born in Belgium in 1862, August De Corte immigrated to the United States in 1897. A interior decorator by trade, De Corte set up shop in Staten Island, New York. Yet his true passion was breeding Belgian homers and Groenendaels, long-haired, black varieties of the Belgian Shepherd breed. Indeed, he’d brought his dogs and pigeons along with him when he immigrated to the US. For over 20 years, he operated a dog and pigeon farm, becoming a pioneer in the breeding of Groenendaels in America. He also was a regular fixture at dog and bird shows during this time.

As a native of Belgium, De Corte undoubtedly kept a close eye on the Great War as it raged across Europe. Accounts of pigeons being used for emergency communication services must’ve intrigued him, given his background as a pigeon fancier. When the US seemed poised to join the conflict at the start of 1917, De Corte sprang into action. According to an affidavit he authored in 1920, De Corte met with Signal Corps officials in New York on February 6, 1917 to give them an in-person demonstration involving a mated pair of Belgian homers, Uncle Sam and Victory. “I proved why pigeons were needed at once by the government for communication work,” he testified, “and how by my patents and methods they could be made immediately available.”

Based on this demonstration, De Corte entered into an advisory relationship with the Signal Corps, meeting and consulting with officers and other civilian advisors throughout 1917 and 1918. De Corte would claim in his 1920 affidavit that he tendered 14 of Uncle Sam and Victory’s offspring to the Signal Corps on April 9th, “two weeks before any other pigeons were used by the War Department.” Another 14 were supplied that same month, six of which “were the first pigeons sent to France to be used by the American Expeditionary Forces.”

Aside from supplying pigeons, De Corte worked toward devising better equipment for the Army’s homers. Many of these devices were for use by soldiers out on scouting or reconnaissance missions—an ideal scenario for using carrier pigeons. He claimed no fewer than five inventions during this period, each of which is described below:

Wire Cage

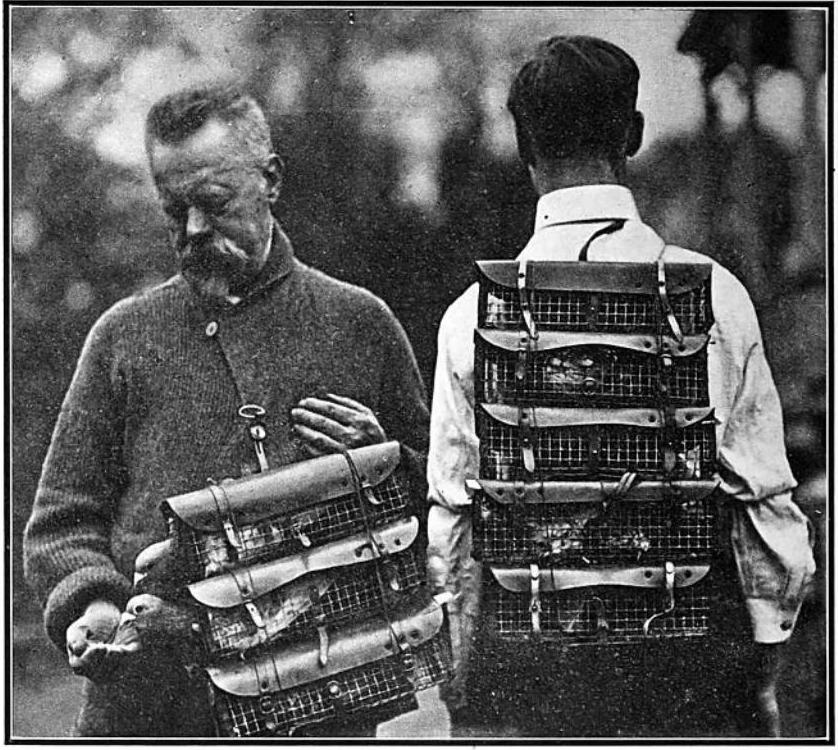

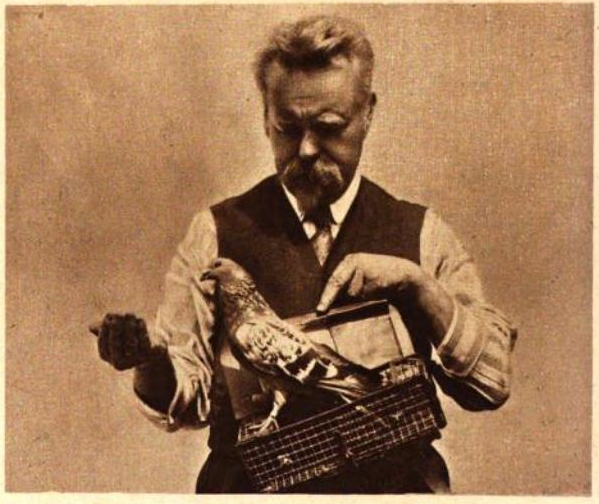

A special, light-weight wire cage was designed for soldiers to carry pigeons while out in the field. It was just large enough to hold one bird securely and comfortably—the bird could stick its head out, but couldn’t fly away. Because the cage was made out of wire, the bird could be fed and a message inserted in its holder without it having to be released.

A leather strap allowed for the cage to be fastened to a button on a soldier’s uniform, permitting it to be worn on the chest or back. A reporter for Scientific American, who personally attached the cage to his vest, noted that it “would offer no appreciable impediment to marching or, within moderation, even to fighting.” The cage could also be strapped to a dog in case human couriers were unavailable—De Corte’s Groenendaels happily served as models in a series of photographs.

A leather cover folded over the top of the cage to protect the pigeon from the elements. The inside of the cover had room for pencils, paper, and grain. The cover also served as a writing table.

Parachute & Balloon

These two inventions—both of which were intended to be attached to the wire cage—were for sending pigeons to soldiers separated from their main units. If their exact positions were unknown, an aviator could use the parachute to airdrop the pigeons over their approximate area. If their positions were known, pigeons could be sent to them via the balloon, assuming a favorable wind was blowing in that direction.

Message Holder

De Corte created a new type of holster for attaching messages to a pigeon’s body. The device consisted of a rubber tube attached to a leather harness. The harness slid over the pigeon’s neck, under its wings, and around its legs, making it nearly impossible to be seen. Meanwhile, the tube hung low near the pigeon’s feet—this was to allow the tail feathers and wings to camouflage the tube when the bird was in flight. In De Corte’s opinion, this message holder would make it difficult for enemy troops to spot Army pigeons.

Portable Loft

De Corte developed a portable pigeon loft for mobile operations on the battlefield. It had four wheels, allowing it to be towed by trucks. The interior could house 75 pigeons along with sufficient quantities of food and water. The loft was configured so that a returning bird’s entry would trigger a bell. Once inside the coop, the pigeon was trapped in an interior compartment until it was retrieved. A photograph taken in late-1918 shows that it could be disguised effectively with camouflage to blend into its surroundings. Evidently proud of this invention, De Corte applied for a patent in May 1918.

With the War over, De Corte presented a claim to the War Department in June 1919 for his services. After all, he’d helped the Pigeon Service immensely by supplying birds and designing wartime equipment. “My birds, at the front in the war, by their efficiency and helpfulness were the means of saving thousands of American lives,” he boasted. Meanwhile, his interior decorating business had suffered, given his sole focus on assisting the Signal Corps. The War Department saw things differently, however. It claimed that De Corte knew from the outset that no civilian would receive any compensation for services rendered. The Army’s Judge Advocate General Office agreed with the agency’s position, holding that “[s]ervices rendered gratuitously and accepted on that premise can not thereafter be made the basis of a legal claim for compensation.”

The War Department’s refusal to pay was a terrible blow for De Corte. With his business in shambles, De Corte was now penniless and nearing sixty. “[B]roken in spirit and disappointed because of lack of recognition by the government,” he prepared to sail to Belgium on January 21st, 1920, to spend the rest of his life there. Before leaving, however, he handed off Uncle Sam and Victory—the parents of the first birds in the Pigeon Service—to his representative for display at the upcoming annual Madison Square Garden exhibition. A set of instructions he left for the representative gives us a glimpse into his generalized depression: “Kill my birds after the show and send the bodies to the Museum of Natural History to be mounted and preserved as historic birds.” A wave of outrage swept the fancier world when this leaked out—this was no way to treat the founding birds of the Pigeon Service. The pair were instead auctioned off, with the proceeds going to De Corte.

De Corte returned to Belgium and was never heard from again. It’s a shame that his story ended so tragically. While the War Department was correct from a legal standpoint, it arguably had a moral obligation to pay the man for his services in light of the sacrifices he’d made. Without his assistance, the Signal Corps’ Pigeon Service might never have gotten off the ground. We at Pigeons of War salute De Corte for his achievements.

Sources:

- De Corte, August, “What I’ve Learned From Dogs About Human Nature,” The American Magazine, Vol. 87, Jan. – Jun. 1919, at 60.

- Lamar, Nelson, “Saving Soldiers With Pigeons,” The Wilmington Morning Star, Feb. 11, 1919, at 10.

- “Splendid Exhibit of Poultry,” The New York Herald, Jan. 19, 1919, at 45.

- “The Pigeon Express,” Scientific American, Vol. 119 No. 14, October 5, 1918, at 271.

- “Two Army Pigeons Insured for $5,000,” New York Daily Herald, Jan. 19, 1920, at 20.

- “Victory Near End, So Is Uncle Sam,” New York Daily Herald, Jan. 23, 1920, at 18.

- War Department, Opinions of the Judge Advocate General of the Army, January 1919, at 911-912 (1919).