In discussions about military pigeons, little attention has been paid to how the birds even entered the armed forces. Typically, there were two routes. Some pigeons were like professional servicemembers—born and raised in government lofts, all they knew was a life of military camps and discipline. Others were like draftees—prize-winning racing birds in civilian life, they suddenly found themselves thrust into an active warzone.

This latter group of pigeons provided crucial services during both World Wars. But how did governments get folks to hand over their pigeons to the military? From the 1870s through the 1940s—the golden age of war pigeons—this was an issue of concern. In the event war broke out, a country’s reserve of military pigeons would quickly be depleted. Fresh recruits would have to be drawn from the nation’s fanciers, some of whom might be unwilling to part with them.

France and Germany explored different ways in which civilian fanciers could be compelled to turn over their birds to military authorities. Influenced by recent memories of the Franco-Prussian War, the French legislature passed a law in 1877 granting the military the right to requisition pigeons from fanciers during wartime. To effectuate this law, President Jules Grévy promulgated regulations in 1885 requiring all individual homing pigeon owners and fancier societies to provide annual declarations to their local mayors detailing the number of lofts and pigeons in their possession. The mayors were responsible for compiling this information into a census and forwarding it to the officials in charge of their respective military districts.

Meanwhile, in Germany, fanciers took the lead in building closer ties with the country’s Ministry of War. A supra organization of fancier clubs was formed in 1884 with the ultimate goal of training their pigeons “to become something useful for the Fatherland in the event of war.” The association required its club members to make their pigeons available to the military if war occurred. In recognition of this sacrifice, the German government enacted a law in 1894 extending federal protection over club members’ pigeons. To avail themselves of this benefit, club members had to stamp the imperial seal on their birds’ wings.

Lagging behind its peers, the United States finally had its own military pigeon service when the Navy adopted one in 1896. Fearing that the Navy would not have enough birds in a time of crisis, several fanciers worked with members of Congress to develop legislation that would bring civilian birds into the Navy. On the eve of the Spanish-American War, the legislation was introduced into the House of Representatives and the Senate. Under the proposed law, the National Federation of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers would be required to file annually with the Secretary of State of New Jersey—the state in which the group was headquartered—information about the pigeons owned by its members and the location of their lofts. In the event that war or a civil disaster occurred, the Federation would have to turn all of its birds over to the Secretary of Navy. In exchange, homing pigeons bearing Federation leg bands would receive federal protection, with it being a crime to kill, injure, or trap them.

Critics, however, argued that the bill only protected the pigeons of only one fancier group: the National Federation of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers. While this had been the predominant homing pigeon enthusiast group in America, a faction dissatisfied with the Federation’s internal politics split off and formed their own group in December 1897. This new group, National Association of American Homing Pigeon Fanciers, had quickly become “a far larger, more powerful, progressive and representative body,” much to the Federation’s chagrin. The fanciers who had spearheaded the bill were Federation members, and thus, had carefully drafted it so as to discourage pigeon owners from joining the Association. Put off by this partisan display, legislators referred the bill to the Committee on Naval Affairs, where it ultimately died.

Thankfully, both the Federation and the Association offered up their birds to the Navy when war broke out. It was thought the pigeons could be of service for ships patrolling the coast in search of the dreaded Spanish fleet. To that end, group members in Maryland and Pennsylvania trained their birds to make flights from the coast. Once the birds graduated from training, they were handed over to naval ships stationed nearby. The Spanish fleet, however, never materialized. Instead of relaying enemy intelligence collected by scouting vessels out at sea, the pigeons were used to deliver messages from sailors to friends and family back in the city.

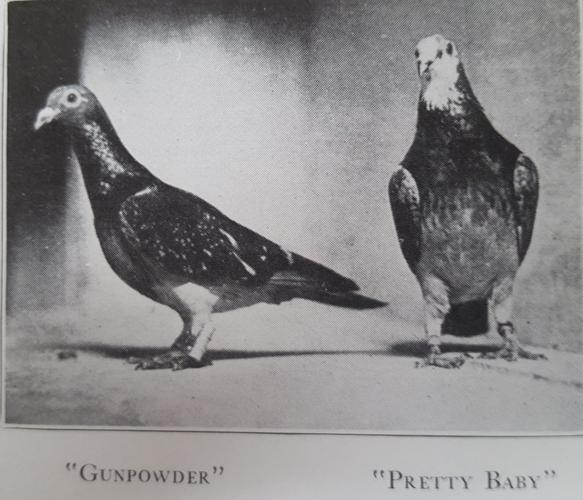

When the US Army entered World War One, it did not have a pigeon service in place. Seeing the success brought to their Allied counterparts, officials decided to set one up. Tasked with this responsibility, the Signal Corps relied on the generosity and patriotism of dozens of fanciers in getting the service up and running. The majority of these birds were used for breeding, providing the Army with its own pigeons. However, a bird donated by an American fancier, Gunpowder, delivered the Army’s first message on March 17th, 1918, carrying the message from the trenches to HQ. As the War entered its final months, the Army’s Pigeon Service found itself in dire need of 1,900 breeding pairs of “specially selected homing pigeons” for use in the American Expeditionary Force. Fearing that not all fanciers would be so kind as to donate their birds, officials sought counsel for the Army’s Judge Advocate General (JAG).

Interpreting the issue under the Fuel and Food Act of 1917, the JAG Office found that homing pigeons were “supplies necessarily required by the Government for in the prosecution of the war and are necessary for public use connected with the common defense.” In the event that a homing pigeon owner refused to turn over their birds to the War Department, the agency had the right to requisition pigeons from that owner. Officials had to issue an order to the owner describing the type and amount of birds needed and informing the individual of the provisions for compensation in the applicable statute. If the owner refused to allow officials to examine the requested birds, then they had the right to seize all the birds it wished and auction off any that weren’t needed. Because the opinion was issued just two weeks before the Armistice, the Pigeon Service never had the opportunity to exercise its newly granted requisition powers. The relevant statute was repealed in 1921, nullifying the JAG Office’s opinion.

Twenty-three years later, the US found itself at war yet again. This time, the US Army had a pigeon service in place. But military officials knew that the Army’s peacetime supply of birds would not be enough to meet the country’s mobilization needs. The vast majority of war pigeons would have to come from civilian fanciers, of which there were 12,500. While many of these fanciers had already registered their birds under a plan put into effect by the Army’s Chief Signal Officer, the Army desired more control over this vast pool of potential recruits.

In consultations with Attorney General Francis Biddle, the War Department developed a bill that would’ve enlarged the President’s authority over pigeons not owned by the United States. The bill, as introduced into Congress in April 1943, would’ve allowed the President to issue regulations governing the possession, control, maintenance, and use of all homing pigeons and their respective lofts. Violators would’ve been fined $100 or faced imprisonment of not more than 6 months, or subject to both fines and imprisonment.

The bill passed through the House, but had a frosty reception in the Senate. Senators saw the bill as an unnecessary power grab by the President’s administration. Although a sub-committee was appointed to investigate the bill, it ultimately failed to become law. Despite the Army’s fears, the nation’s fanciers rose to the call of duty. Of the 54,000 pigeons that served in the Signal Corps during World War II, approximately 40,000 were donated by fanciers. Some of these birds went to breeding centers, while others were sent to North Africa and the Southwestern Pacific. By early 1944, Signal Corps officials began informing fanciers that their pigeons were no longer needed, as the government had bred thousands of its own birds

So, unlike France or Germany, the United States never managed to implement a pigeon draft, but its fanciers were more than willing to part with their beloved birds. It’s a tribute to their character that these individuals gave away champion pigeons for free when their nation came calling. We at Pigeons of War consider these folks heroes, worthy of praise. Without them, the US military’s pigeon programs would have been doomed from the start.

Sources:

- A History of Army Communications and Electronics at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, 1917-2007 at 25, (2008).

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 126 (1888).

- “Biddle Asks Law to Regulate All Carrier Pigeons,” The Miami News, April 18, 1943, at 4.

- Blazich, Frank, “Feathers,” Army History, Fall 2020, No. 117, at 34-37, 42.

- Bulletin des lois de la République franc̜aise, Volume 12, at 796-797 (1886).

- “Carrier Pigeons for Service in War,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Mar. 2, 1898.

- “Chaffey Sending Army Gift of 34 Homing Pigeons,” The Pomona Progress Bulletin, Jan. 21, 1944, at 5.

- Der Brieftaubensport, Jean Bungartz, at 240, (1889).

- “Flock of Homers From the Dixie,” The Baltimore Sun, June 4, 1898, at 8.

- House Reports, 78th Congress, 1st Session: Miscellaneous, Vol. III, at 967-968 (1943).

- Hudson, Billy, “Pigeon Racing Local Hobby,” The Lexington Herald, June 20, 1944.

- Kidney, Daniel, “Well, Pigeons At Least, Escape Dictatorship,” The Akron Beacon Journal, Nov. 2, 1943.

- Königliche Ministerium Der Öffentlichen Arbeiten, Eisenbahn-Verordnungs-Blatt, at 259 (1894).

- “Pigeon Draft Suspended,” The Billings Gazette, Jan. 10, 1944, at 8.

- “Pigeons for the Navy,” The Baltimore Sun, May 5, 1898, at 12.

- “To Protect Homers By National Laws,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, Mar. 7, 1898, at 4.

- War Department, Opinions of the Judge Advocate General of the Army: 1918, Vol. 2, at 927-928 (191).

- “War Pigeons Training,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, May 4, 1898, at 4.