Since the end of the Second World War, most of the world’s militaries have decommissioned their pigeon services. A few, however, have held onto their birds. In this ongoing series, we’ll take a closer look at these holdouts.

For nearly 80 years, almost every European military had a pigeon service at one point or another. These birds served bravely in both World Wars and in minor excursions. Yet, by the start of the 21st Century, they were all gone—save for a single dovecote in France.

France’s possession of the last military loft in Europe isn’t surprising. After all, France pioneered the use of pigeons in combat during the Franco-Prussian War. From 1870 to 1871, the Prussian Army tried to cut off Paris from the outside world, but French fanciers smuggled pigeons in hot air balloons to Tours and other cities, informing government officials of their plight. French military officials, seeing the benefits, implemented a pigeon service several years later. By 1901, all of the forts on the eastern and northern frontier had pigeon stations, allowing for contact with Paris. Aside from linking forts with Paris, the French military found other uses for its pigeons. The French cavalry incorporated pigeons into their reconnaissance work, while naval ships used the birds to remain in contact with the coast.

During the Great War, the country put nearly 30,000 pigeons to work. They served courageously during the Battle of Verdun—Le Vaillant, a blue bar hen, flew through shellfire and gas clouds to deliver the last message of Fort Vaux before it fell to the Germans. Barely alive after inhaling poison gas, she pulled through and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Owing to the speed of the blitzkrieg, the French military did not have the opportunity to deploy its pigeons during the Second World War—Members of the Resistance, however, used over 16,000 pigeons in spy networks throughout the war.

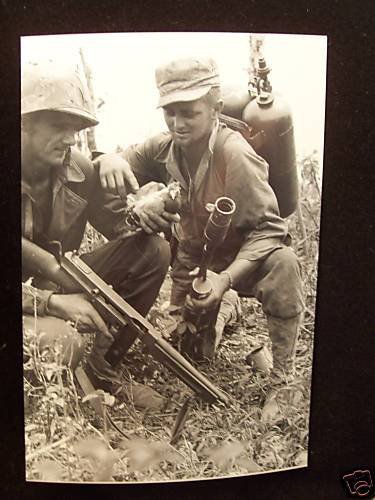

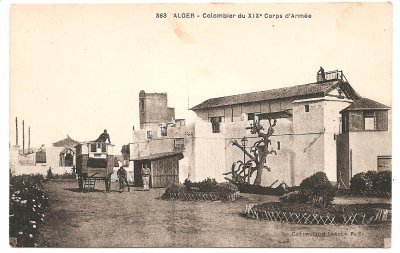

The birds later played roles in France’s subsequent decolonization wars. In the First Indochina War, the pigeons were headquartered at Fort de Cay May in Saigon. Not suited to the tropical climate, it took a year of breeding to develop a pigeon acclimated to the area. These efforts paid off, as pigeons ably assisted French outposts in An Khê and Ayun Pa, De Dak Bot and Nam Định. At Nam Định, for instance, the French troops found themselves encircled by enemy forces. Using their pigeons, they were able to request backup from Saigon. In the Algerian War, a central military loft was installed in the suburbs of Algiers. As in the prior conflict, the pigeons linked isolated outposts with military HQ.

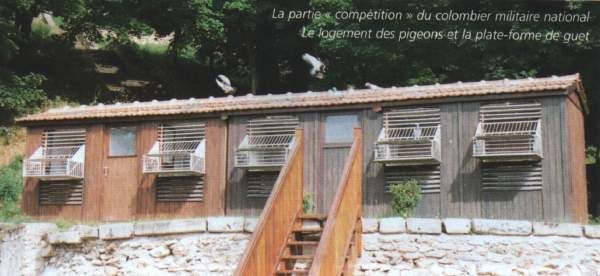

Following the Algerian War, France started decommissioning its military pigeons, seeing little need for them in an age of advanced electronics. However, a group of officers, headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Revon, pleaded with President Charles de Gaulle to spare a single dovecote for tradition’s sake. He agreed, preserving the military loft at Camp des Loges in Saint-Germain-en-Laye and assigning it to the 8th Regiment of Transmission, the unit responsible for the military’s telecommunications and information systems. In 1981, the loft was relocated to Mont Valérien, a fortress in the western suburbs of Paris.

Mont Valérien’s dovecote houses around 200 pigeons, which are overseen by a single maréchal de logis, a type of non-commissioned officer. The maréchal oversees all aspects of the pigeons’ lives from the cradle to the grave: he cleans the dovecote, procures their food, selects the best birds for breeding, and provides basic veterinary care. To keep the pigeons fit for their ceremonial duties, he trains the birds for races that range from 100km to 1,000km. Their speeds vary from 60 kph to 120 kph, depending upon the weather. Tradition dictates that each new maréchal adopt one of the flock as his or her own. The current maréchal has named his protege Vaillant—the name is appropriate, as the pigeon is the champion of the loft.

Like the Uruguayan Army’s pigeons, Mont Valérien’s pigeons are used strictly for ceremonial services, taking part in civilian competitions and official military demonstrations. To educate the public further, a museum has been built near the loft, explaining the birds’ historical role in the French military. Nevertheless, the current maréchal acknowledges that they might be of use in a total blackout brought on by war. “[T]hey would need extra specialised training,” he clarifies, “but they would be fit and healthy for duty if required.” In the event of such a blackout, the maréchal has already chosen Vaillant to deliver the first official message to Paris.

One lawmaker has expressed an interest in revitalizing the Army’s pigeon service. Jean-Pierre Decool, a senator representing the Nord department, argues that the French Army should breed more pigeons. A pigeon fancier himself, in July 2012, he sent a letter to the Defense Minister, asking him to clarify France’s military pigeon strategy. The Minister wrote back, informing Decool that in the event of widespread communications failure, the country’s 20,000 pigeon keepers could be called upon to provide their birds to the military. Acknowledging that little appetite currently exists for increasing the military’s flock, Decool has also advocated for lofts to be erected near nuclear power stations “so they can keep communications going in case of an accident.” The idea came to him in the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear accident. “I said to myself that carrier pigeons could have played a crucial role in communications between the radioactive zones and the outside world, without exposing people.” As Decool envisions it, a mobile loft could be set up inside the security permit around the reactor, while a stationary loft could be established about 30 miles away. By regularly exchanging birds between the lofts, communication could be maintained in the event of an incident. So far, Electricité de France, the utility in charge of the country’s nuclear power plants, has not expressed an interest in Decool’s plan.

We at Pigeons of War applaud the French Army’s decision to keep an active loft. Not only is it a tangible reminder of 150 years of history, the loft could prove to be a valuable resource in a total blackout brought on by war or natural disaster. We encourage other European countries to follow suit and revive a military tradition that has sadly gone dormant.

Sources:

- Army ‘Needs More Carrier Pigeons’. The Connexion, 24 Aug. 2012, https://www.connexionfrance.com/article/Archive/Army-needs-more-carrier-pigeons.

- Bassine, Olivier. Un Colombier Militaire à St-Germain. 78 Actu, 16 Jan. 2016, https://actu.fr/ile-de-france/saint-germain-en-laye_78551/un-colombier-militaire-a-st-germain_12590897.html.

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 249 (1901).

- Florence Calvet, Jean-Paul Demonchaux, Régis Lamand et Gilles Bornert, « Une brève histoire de la colombophilie », Revue historique des armées [En ligne], 248 | 2007, mis en ligne le 16 juillet 2008, consulté le 25 mai 2022. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/rha/1403

- Hanks, Jane. “France’s Army Platoon of Carrier Pigeons Is One of Its Kind in Europe.” The Connexion, 17 June 2021, https://www.connexionfrance.com/article/Practical/Work/France-s-army-platoon-of-carrier-pigeons-is-one-of-its-kind-in-Europe.

- Les Derniers Pigeons Soldats D’europe.” Tristan Reynaud Photographe, https://tristanreynaud.com/fr/portfolio-27463-les-derniers-pigeons-soldats-deurope.

- Marie-Pont, Julia. Des Animaux, Des Guerres, Et Des Hommes. 2003, https://oatao.univ-toulouse.fr/1972/1/celdran_1972.pdf.

- Parussini, Gabriele. “French Could Return the Military’s Carrier Pigeons to Active Duty.” The Wall Street Journal, 11 Nov. 2012, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324439804578104933926157320#project%3DSLIDESHOW08%26s%3DSB10001424127887324439804578105210570961132%26articleTabs%3Darticle.

- Ulbrich, Jeffrey. Today’s Focus: Hi-Tech French Army Still Has Faithful Pigeons. Associated Press, 13 Dec. 1985, https://apnews.com/article/a20f3c8d434e397c3a3c6ba83470622b.