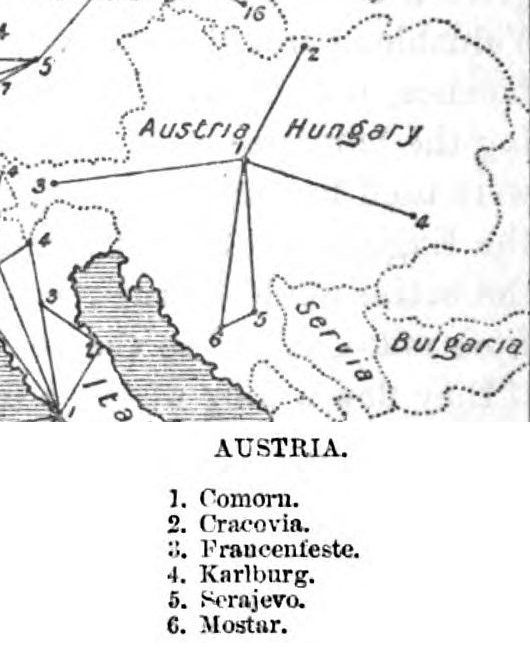

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was founded in 1867, the result of a compromise between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary. It entered the world stage as a Great Power, and like all the others, raced to establish a military pigeon service in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War. The first military pigeon station was established at Komorn (Komárom) in 1875. This loft served as the point from which all subsequent stations were linked. By the 1890s, stations had been built along the Empire’s borders—there were military lofts in Cracow (Krakow) in Galicia; Franzenfest in Tyrol; Karlsburg in Transylvania; Sarajevo and Mostar in Bosnia and Herzegovina; and Trieste in Carniola. Unofficial stations were also privately maintained by some officers. The initial focus was on providing communication services for fortresses in mountainous districts, where telegraphic or visual signaling was impossible. Through diligent training, these birds attained speeds of 1 km over short flights.

Impressed with the pigeons’ abilities to transmit despatches between forts, military officials began training the birds for other military specialties. Attention was paid to the birds’ potential for reconnaissance work. In 1905, the Army planned a series of maneuvers in which these skills would be tested. Several non-commissioned officers were assigned to reconnoitering patrols or scouting units in the Enns–Amstetten–Haag zone and tasked with relaying important information to Linz, where the despatches would be reviewed and telegraphed to the appropriate destination. “Each non-commissioned officer carried four pigeons in a small square cage fixed to the end of a bamboo stick, which was itself placed in a sort of socket fixed to the stirrup,” one military journal recounted. Good results were achieved through these exercises, yet some of the pigeons “suffered from great fatigue caused by the long confinement in such a restricted space.”

The Army’s balloon section also experimented with pigeons, thanks to the generosity of a private breeder who offered his birds to the unit annually. The birds were taken up in the balloons and released whenever the pilot wished to communicate with officials on the ground. In contrast to similar attempts in other countries, the pigeons had a high success rate. Losses weren’t uncommon, however. During a balloon release on June 20, 1899, half of the pigeons failed to return, though three returned after nine months, one of which still bore a despatch.

The Austro-Hungarian Navy had a pigeon loft at Pola (Pula) in modern-day Croatia. Housing 120 birds, the naval station trained them for service along the Adriatic Sea, attaining distances of over 250 miles away from the home loft. In 1889, the Empress took one of these birds on a trip to Pola to Corfu, Greece, releasing it with a message for her daughter, the Archduchess. Unfortunately, a peasant shot the bird. This led to calls for laws to protect the Empire’s homing pigeons from shooting.

As the Service expanded, the military considered reaching out to civilians to bear the cost and time for training pigeons for military service. Pigeon rearing, however, had never really taken off in Austria-Hungary. Only a few associations existed and these groups didn’t possess many birds. The government tried to cultivate an interest by awarding prizes for races in Vienna and other cities, but the prize money was a rather insignificant amount. Free wood for building lofts was also provided by the government to officers and government employees who agreed to raise pigeons for the military’s use. Railroad companies joined in, offering reduced fares for those taking pigeons on long-distance training flights. In spite of these efforts, pigeon fancy remained a rich man’s pastime in the Empire.

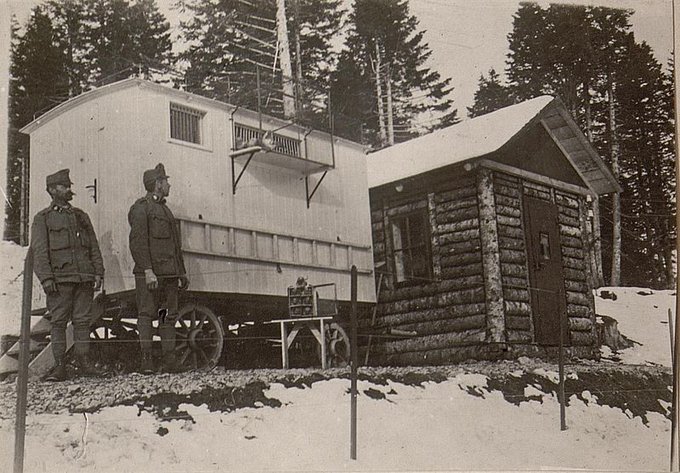

When the Great War broke out, Austro-Hungarian soldiers carried their birds with them into battle. Early on, pigeons came to the aid of soldiers defending the Galician city of Przemysl against the Russians, allowing for contact to be maintained with Vienna throughout the fall of 1914. Aside from conveying despatches, pigeons were also used for espionage. In 1915, the Italian government seized the Albanian ship La Bella Scutarina off the coast of Bari on charges that the crew were involved in a spy ring. Evidently, the Albanian crew, traveling under the cover of a neutral vessel, was collecting intelligence on Italian positions in the Adriatic Sea and sending the info back to Austro-Hungarian officials via pigeons. By the final years of the War, the Austro-Hungarian Pigeon Service had embraced many of the innovations developed during the conflict—pigeons were transported in mobile coops and even had special cages to protect them from gas attacks.

The challenges brought on by the Great War amplified pre-existing tensions within the multi-ethnic Empire. On October 31, 1918, Austria and Hungary dissolved their union. Two weeks later, the War ended. The Dual Monarchy had lasted for 51 years, just eight years longer than its Pigeon Service. All that remains these days is a former station in Trebinje, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Run by the Museum of Herzegovina, it has hosted workshops for local children, teaching them of the role pigeons played in the city’s imperial past.

Sources:

- “Albanians Sentenced for Aiding Austrians,” Asheville Gazette-News, Sept. 3, 1915, at 1.

- Allatt, H. T. W., “The Use of Pigeons as Messengers in War and the Military Pigeon Systems of Europe,” Journal of the Royal United Service, at 129-130 (1888).

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 237 (1901).

- Department of Marine, “Report on Messenger Pigeons,” Twenty-Third Annual Report of the Department of Marine, for the Fiscal Year Ended 30th June, 1890, at 206.

- “Message from Przemysl by Pigeon Post,” The Charlotte News, Nov. 28, 1914, at 6.

- Niblack, Albert, “Naval Signaling,” The Proceedings of the Naval Institute, Vol. 18/4/64, 1892, at 454.

- “Sundries,” The United Service Magazine, Vol. 32, Oct 1905 – Mar. 1906, at 486.

- “The Sad Fate of an Empress’s Carrier-Pigeon,” The Star, Nov. 16, 1889, at 2.