One of the many innovations to come out of the Great War was camouflage. Concealment has been a wartime tactic since time immemorial, but the concept of using stylized patterns to disguise military equipment emerged in the first month of the War. Two French painters who had been mobilized into an artillery regiment hid their guns under branches and canvases painted in colors mimicking the terrain. Impressed with these and other similar efforts, the French Army established a Camouflage Section in August 1915. The Section employed painters and sculptors in workshops throughout the country to develop camouflage techniques. Teams of artists—many of whom came from the cubist tradition—created irregular patterns that could be painted onto artillery pieces, railroad equipment, trucks, and other equipment. These ideas spread and quickly became a fundamental part of modern warfare.

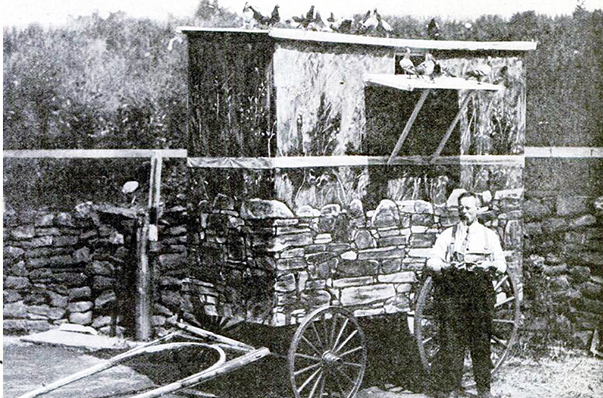

Camouflage methods were eagerly adopted by military pigeon services in both World Wars. The primary focus was hiding the pigeons’ lofts. Large and conspicuous, mobile lofts near the front line were susceptible to attacks by enemy aircraft. Stationing them near a building or under a tree helped, but that wasn’t always an option if the units were in an open field. A simple way to conceal a coop was to paint it entirely olive-drab green. For more advanced techniques, a painter could cover the coop in a melange of brown and green hues, or try to accurately reflect the natural surroundings. In one widely-circulated photograph, a mobile loft has been painstakingly painted to match a stone fence and vegetation in the background. But those tasked with concealing lofts had to be careful that their efforts didn’t confuse the birds. During preparations for the Battle of the Somme, for instance, an army of artists worked feverishly to camouflage the British Army’s equipment. Apparently, they were too good—the concealed coop was so convincing, the pigeons failed to return to their loft.

Officials also experimented with camouflaging pigeons themselves, as their bright patches of white or colored feathers and distinctive outlines made them an easy target for sharpshooters. The first recorded instance of pigeon camouflage occurred during the Battle of Verdun. As the fighting stretched on, the German Crown Prince Wilhelm grew frustrated as the French kept sending for backup with their pigeons. Tired of standing by helplessly while French pigeons flew overhead, he formed a crack battalion to put a stop to this. He recruited experienced trapshooters and equipped them with shotguns. Their task was to shoot down any pigeons spotted flying towards French HQ. As the soldiers shot down bird after the bird, the French had no choice but to camouflage their messengers. Pigeons were dyed completely black so they resembled crows. The subterfuge paid off. One of these mock crows—formerly a milky-white pullet by the name of Babette—was released from behind German lines. The bird carried a message that detailed a planned attack on the Meuse. Thanks to this despatch, Allied forces thwarted the offensive.

Subsequent attempts at camouflaging pigeons utilized the standard swatches of greenish hues. The methods of application varied by country. The British used paint, which worked out in their favor when a painted pigeon saved a regiment during the Battle of the Somme. The Americans apparently used a concoction of chemicals similar to “the drugstore ingredients which brunettes often use to make themselves blonde overnight.” The Germans tried dusting their pigeons with a green powder, but the powder broke down in light rain and caused the feathers to absorb water rapidly. Weighed down, the birds were incapable of flying.

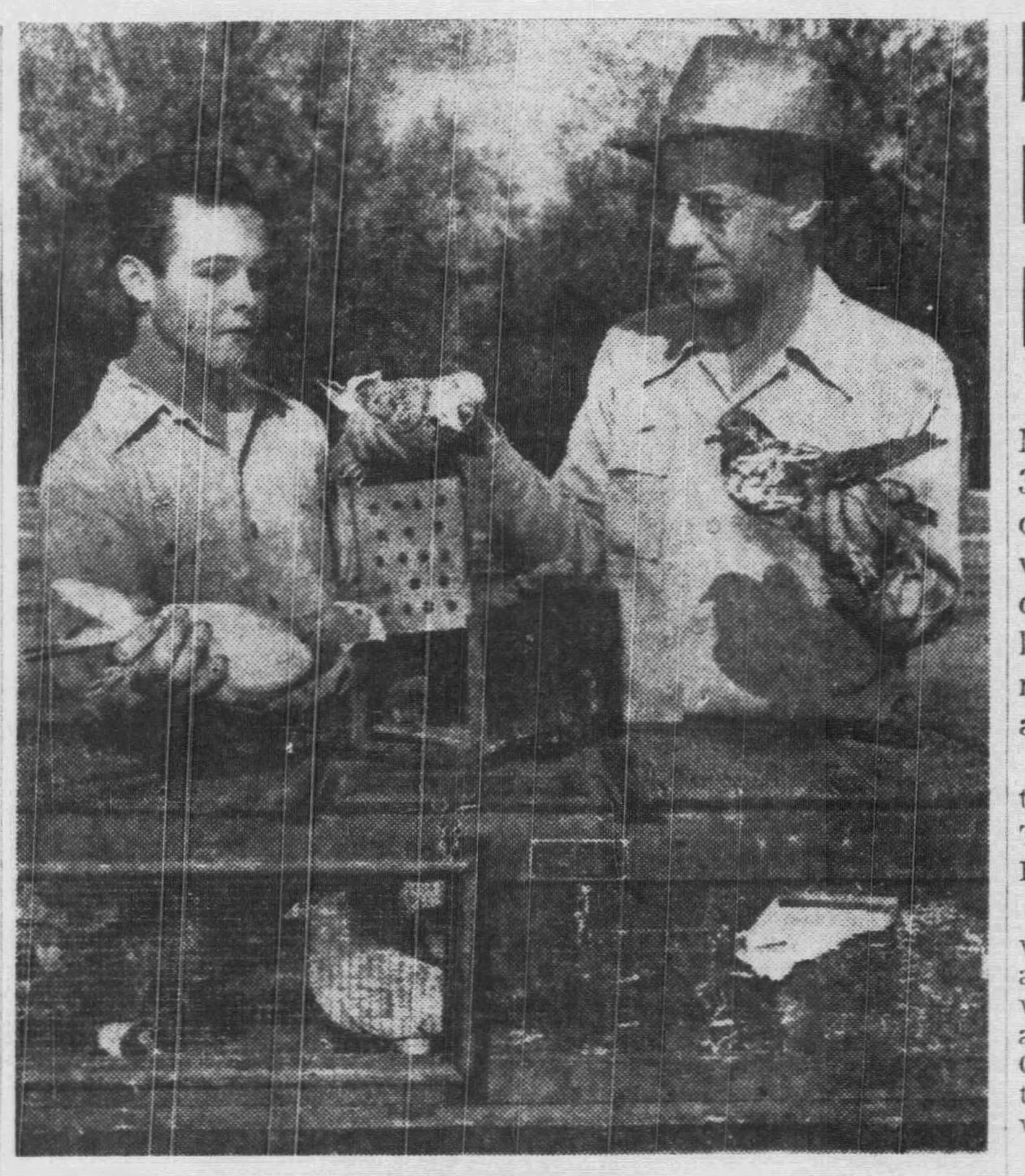

In the years leading up to America’s entry into World War II, Ray Delhauer—a former captain of the US Army Signal Corps’ Pigeon Service—took it upon himself to breed a stealthier bird. Delhauer had served in World War I, training many of the Pigeon Service’s officers and birds. By 1940, he had retired from the Army and was teaching at a high school in Ontario, California. Delhauer still had one foot in the pigeon world, though. He had formed a club for his students to breed and raise pigeons. Together, they worked to develop an elite bird that might be useful for the Army, mixing Black Bovyns—a breed suited for flights over the Swiss Alps—with grizzled veterans of the First World War. Included amongst their ancestors were Allied superstars Mocker and Spike and Germany’s Kaiser and Fraulein.

Satisfied with the birds’ performances, Delhauer and his students then shifted focus. The new goal was to make the pigeons’ coloration less perceptible. Through intense breeding and crossbreeding, Delahauer developed a half-dozen color mixtures for use in specific environments. A blue-rust variety was reportedly nearly invisible over one type of terrain, while a mottled gray-and-white strain blended in with urban skies. After the US entered World War II, the Army took an interest in Delhauer’s birds. In 1943, he shipped batches of them to Army sites in South Carolina, New Jersey, and Missouri, where they were incorporated into military breeding programs. By the end of the War, Delhauer had donated over 400 camouflaged pigeons to the Army.

Camouflage forever altered approaches to concealing military equipment. By disguising pigeons and their coops, militaries ensured that emergency communication services were readily available. Undoubtedly, many more lives were saved, thanks to the ingenuity of artists.

Sources:

- “Camouflage.” International Encyclopedia of the First World War, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/camouflage.

- “Camouflaged Carrier Pigeons Developed for Army Use with Aid of School Boys,” The Paterson Morning Call, Oct. 11, 1941, at 12.

- “Camouflaged Pigeons Displayed at Ontario,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Apr. 11, 1943, at 13.

- “Death Claims Pigeon,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Aug. 8, 1948, at 19.

- March, Eva, The Little Book of the War, at 76 (1918).

- Naether, Carl, The Book of the Racing Pigeon, at 58 (1950).

- “Pigeons Are Bred with Camouflage for War Service,” Popular Mechanics, Vol. 138, No. 1, January 1941, at 81.

- “Pigeons Camouflaged to Escape Teuton Snipers,” Lansing State Journal, May 6, 1918, at 10.

- “Pigeons Prepared for Easter Sunrise,” The San Bernardino County Sun, Apr. 5, 1939, at 14.

- “Saves Regiment,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, Nov. 19, 1917, at 3.

- “School Gives 200 Birds to Army Pigeon Center,” The Los Angeles Times, Nov. 29, 1943, at 10.

- The United States Army, The Pigeoneer, at 86 (1924).

- “They Winged Their Way Through Skies of Steel,” The American Legion Weekly, Vol. 1, No. 9, Aug. 29, 1919, at 16-18.

- “Train in France,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, Nov. 19, 1917, at 3.

One response to “Flying Incognito: Pigeons in Camouflage”

I’m very much enjoying these posts❣️ They are a lovely combination of history & birds. What could be better❓😁❤️ Thanks Justin.

LikeLiked by 1 person