Military pigeons have frequently inspired creators. That’s not surprising—their heroic deliveries of important battlefield dispatches amidst torrents of gunfire are ripe for artistic endeavors. Cher Ami’s transmission of the message that saved hundreds of American soldiers is portrayed in the 2001 film The Lost Battalion. The BBC sitcom Blackadder humously depicted the consequences of shooting a military pigeon. The video game Battlefield 1 allows the player to control a pigeon as it carries a message from a tank crew in distress.

But what about theater? Has anyone ever mounted a production featuring war birds?

In the final year of the Great War, playwright Seymour Obermer completed By Pigeon Post, a play revolving around military pigeons. Born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1867, he moved to the United Kingdom as a young man and became an importer of American automobiles. At some point in the 1900s, the theater bug bit Oberme and he began writing plays. He wrote two under his own name before adopting the nom de plume Austin Page for his subsequent works.

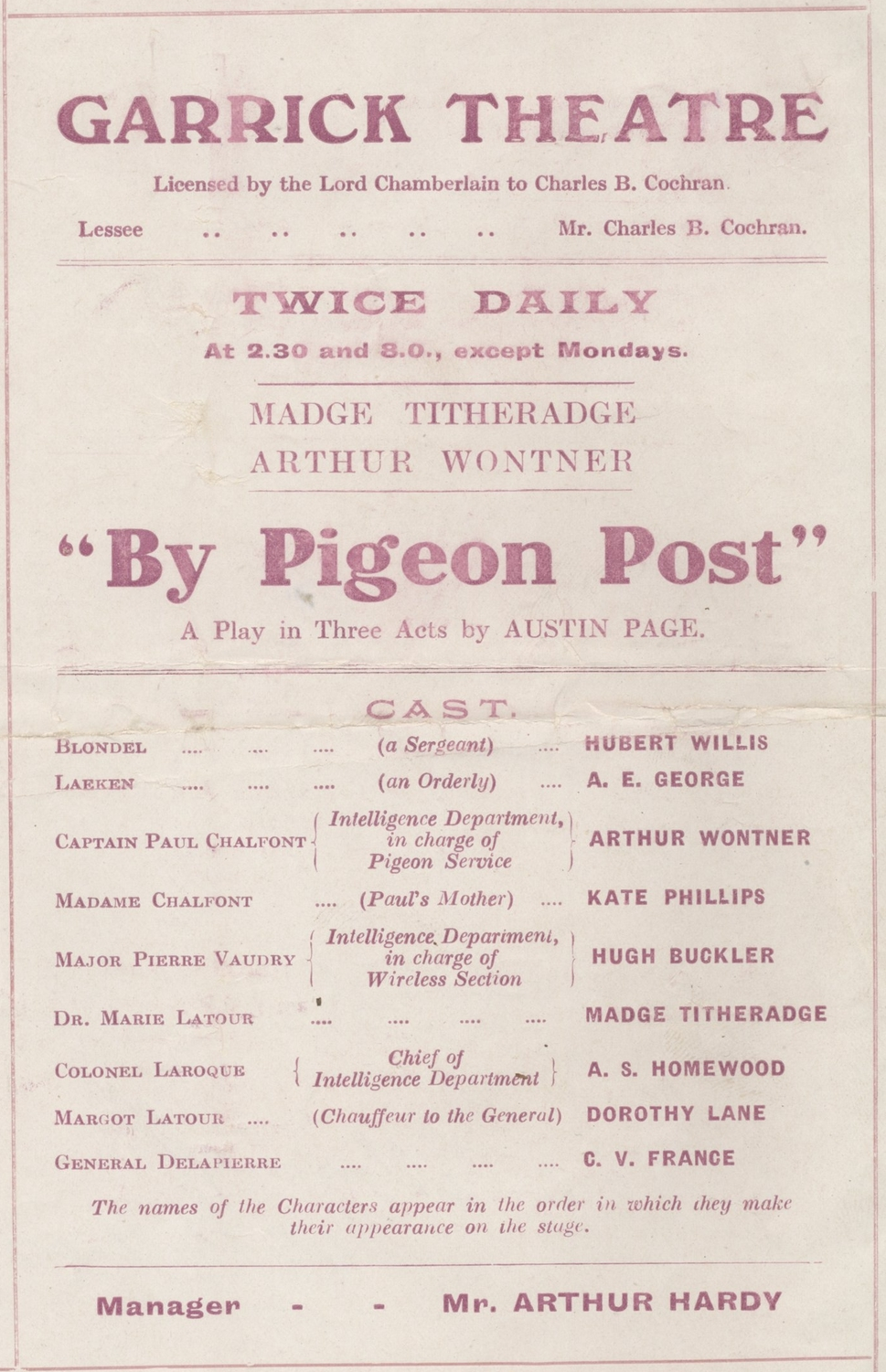

Oberme’s play was the latest in a series of melodramatic spy plays that emerged during the Great War. We have not been able to find an actual copy of the script. Still, a summary of the play can be reconstructed from various sources. The setting is French Lorraine, around 20 miles away from the front. The scenes take place in the library of a chateau that has been converted into an intelligence office; it includes both a pigeon loft and wireless station. The characters are all members of the French Army. Captain Paul Chalfont, the play’s protagonist, is the head of the French Army’s Pigeon Service. He is anxiously awaiting the arrival of a pigeon sent from behind German lines with information about a forthcoming plan of attack. Major Pierre Vaudry, the cantankerous head of the Wireless Section, is the play’s villain; he is actually a German spy working with his orderly Laeken, a secret German citizen posing as a Fleming. Marie Latour, an Army doctor, is the heroine of the play—both Paul and Pierre are in love with her.

In Act I, Pierre and Laeken interfere with Paul’s pigeons, making the Service look ineffective to his superiors. Paul, distressed that his bird has yet to arrive, volunteers to cross the German lines in disguise and search for the pigeon. Laeken eagerly agrees to accompany Paul on his quest. Act II commences with Laeken and Paul’s return, where it appears that Paul is suffering memory loss from shell shock. It is revealed that Laeken actually struck Paul on the head with the butt of his rifle to steal secret plans the Captain was carrying. Laeken discovered the plans were fake, so he brought the Captain back to the chateau, attributing his memory loss to shell shock. Paul is faking his symptoms, however, and with the help of Marie, has Laeken and Pierre charged with spying. In Act III, Paul’s pigeon returns to the chateau with the needed information, redeeming the Service. The spies are tried for treason and convicted—Pierre commits suicide by jumping off a high tower, while Laeken is shot. Amidst the drama, a comedic subplot is present involving a French General’s love for his driver, who happens to be Marie’s sister.

To add a touch of realism, the script called for 20 live homing pigeons to be featured in the chateau’s aviary. The idea was to give people a glimpse of a functioning pigeon service. Over the course of the play, audiences would see several pigeons arrive on stage with messages and others being fitted with dispatches for delivery.

Like all productions of the wartime period, the script had to be submitted to the British authorities for review. The censors left most of the play intact, but struck the script’s direction to include the sound of gunfire at the end of Act II. “This is quite unnecessary to the play and on an air raid night might quite possibly be alarming,” one censor chided.

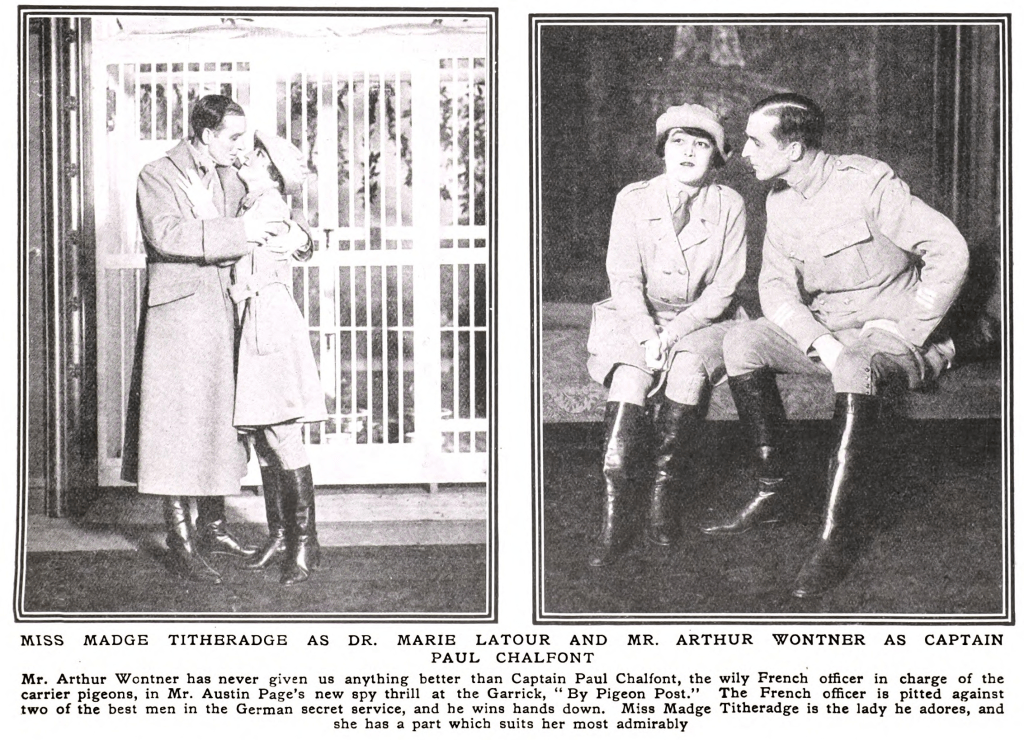

By Pigeon Post debuted at the Garrick Theatre in London on March 30, 1918. Among the actors starring in it was Arthur Wontner, who would go on to play Sherlock Holmes in a series of films in the ‘30s. It was a smash hit with audiences throughout the United Kingdom. Queen Mary viewed it and said it was the best play she’d seen in years. By the time the show ended in 1920, nearly 400 productions had been staged.

While it was running in London, Oberme traveled to America to shop around his play. Several producers were interested in the script, but balked at the price. The Broadway impresario Florenz Ziegfeld, however, liked the play and paid the asking price of $7,000; “A few thousand dollars more or less mean little in this manager’s life,” a theater magazine remarked wryly. Long known for his light-hearted Ziegfeld Follies, this would be his first drama.

Ziegfeld’s production of the play debuted on Broadway exactly two weeks after the War had ended. American audiences were less than enthralled with the show. Critics felt that the story had lost much of its emotional force now that troops would soon be returning home. Indeed, for many playgoers, the pigeons on stage were the best part: “The pigeons themselves are very good and sympathetic. Their cooing and fluttering in a cage give the production its chief interest,” declared a critic. The show ended after a nearly three week run.

In the years since, the play has been entirely forgotten. The last production was in 1940 at the Garrick, when Britain found itself once again at War with Germany. Modern audiences would likely find it to be hopelessly dated, as tastes have soured on melodramas. Nonetheless, a timely theme is present throughout—the clash between technology and nature. It’s significant that the villain of the play is in charge of the military’s wireless service. His way represents the modern method of sending messages, using machinery to communicate through the airwaves. Relying solely on animal power, Paul’s pigeon post is a relic of a bygone era. Yet, it is only through sabotage that Paul’s pigeons fail, and, in the end, they prove triumphant. This has remained a powerful theme in film and television to this day.

We at Pigeons of War would love to see a modern performance. Any readers interested in mounting a production?

Sources:

- “A New and Thrilling Spy Play,” The Tatler, Vol. 68, No. 877, April 1918, at 61.

- “By Pigeon Post.” Great War Theatre,https://www.greatwartheatre.org.uk/db/script/2465/.

- “‘By Pigeon Post,’” The Looker-on, Feb. 22, 1919, at 15.

- “‘By Pigeon Post’ at Cohan Theater,” The Standard Union, Nov. 26, 1918, at 5.

- “‘By Pigeon Post,’ at the Garrick Theatre,” The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, Vol. 89, Apr. 27, 1918, at 234.

- Darnton, Charles, “‘‘By Pigeon Post’ Fails to Carry,” The Evening World, Dec. 5, 1918, at 5.

- Maunder, Andrew, British Literature of World War I, Vol. 5, at xciv (2011).

- “Next Week — ‘By Pigeon Post,’” Folkestone, Hythe, Sandgate and Cheriton Herald, Aug. 31, 1918, at 16.

- “What’s What in the Theater,” The Green Book, Vol. 21, No. 1, Jan. 1919, at 30.