They got a name for the winners in the world

And I want a name when I lose

They call Alabama the Crimson Tide

Call me Deacon Blues

The jazz-rock group Steely Dan celebrated dignified loserdom in their 1977 song “Deacon Blues.” As the above passage suggests, the song’s protagonist—a hapless daydreamer—wants to be remembered in spite of his failures. In the annals of military pigeon history, only the winners are remembered. Subjects of books, poems and even film, these pigeons achieved fame by delivering messages at great peril to themselves. They are often bestowed with grandiose names in recognition of their valor—Cheri Ami, President Wilson, Lord Adelaide, Lady Ethel, to name a few.

For every war pigeon that enters the history books, there are hundreds of thousands—if not millions— that are unknown to the public. Some of these pigeons were merely adequate at their jobs or never had the opportunity to deliver a message of real significance. Many, however, were simply lousy homing pigeons. You won’t find any poems written about them. Why would anyone want to commemorate a bird that couldn’t even do its job?

Arguably, at least some of these so-called losers have been unfairly consigned to the dustbin of history. Even though they lacked the chops for wartime service, maybe these birds had other talents that’ve been overlooked. Take Old Satchelback, for example.

Old Satchelback served in the US Army Signal Corps during the final months of the Great War. Early on, his trainers realized that the pigeon was not a top-tier athlete. “He isn’t what may be called a good bird,” declared one newspaper article. Nor was he “as fast on the wing” as the other birds in his loft. In fact, Old Satchelback was regarded as “one of the laziest birds in the A.E.F.” because of his failure to take flying seriously. Entrusted with the transmission of vital information, Old Satchelback didn’t see the need for a rapid delivery. Flying for long stretches tired him out, so he frequently cut flights short and walked the rest of the way back. Given that pigeons are incapable of walking more than 2 miles an hour, Old Satchelback’s leisurely strolls were a very inefficient way of delivering urgent messages from the front.

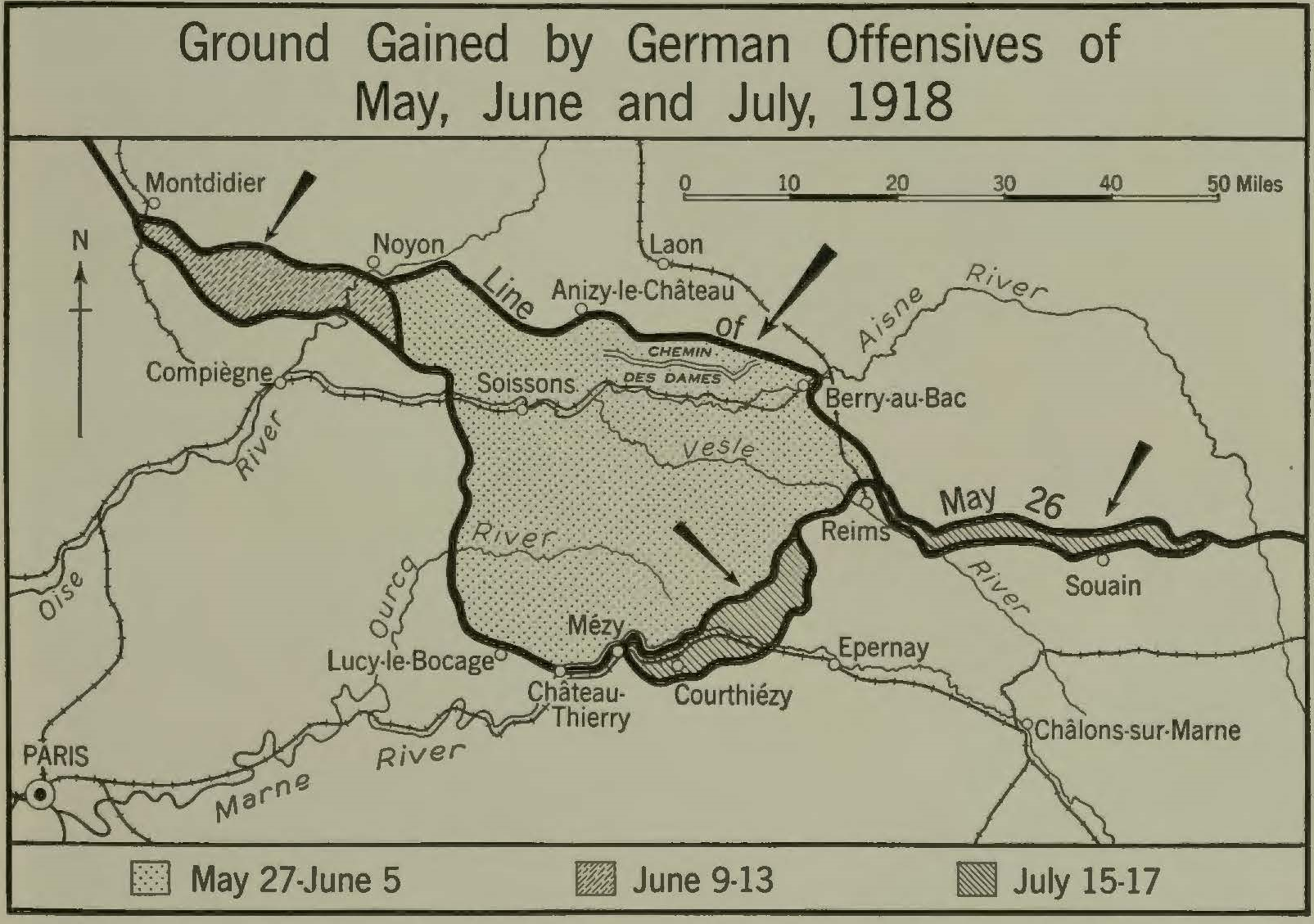

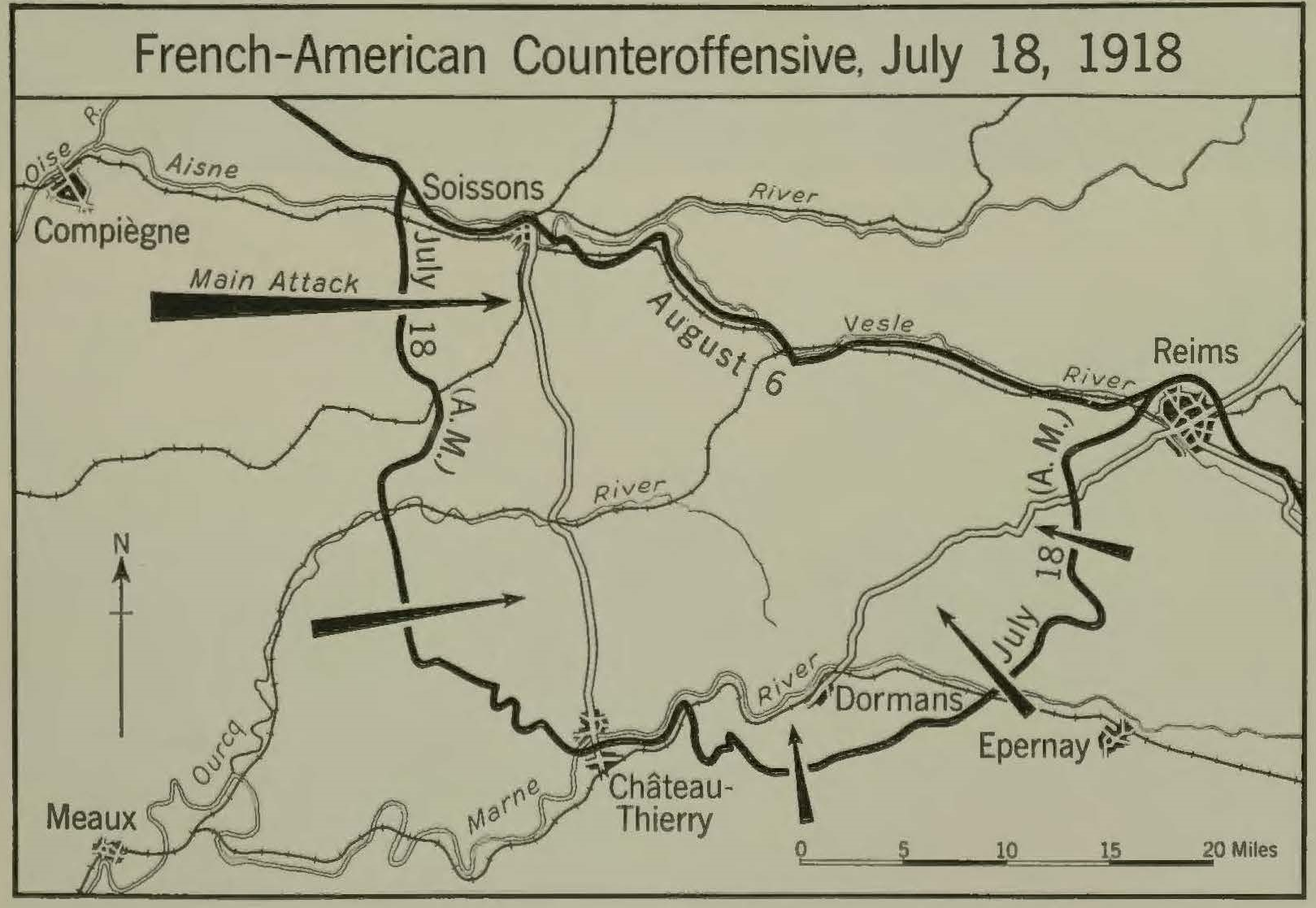

Old Satchelback’s laziness reached epic proportions at the Vesle Front in northeastern France. Throughout July and August 1918, Allied forces pushed German troops out of the Marne Salient and back past the Vesle River. In early August, three American divisions were stationed along the Vesle, tasked with keeping the Germans from crossing the River. The Vesle Front was the site of fierce fighting for nearly a month—the Battle of Fismes and Fismette, for instance, involved street fighting and flamethrower attacks.

Amidst this maelstrom of violence, Old Satchelback was taken to the Front for some unknown reason and released with a message for HQ. True to his nature, the bird soon tired of flying and sought out a road. He spotted one and landed. As he scampered down the path, he stumbled across a section that was pockmarked with shell craters. A normal pigeon encountering such an obstacle probably would’ve taken flight. But Old Satchelback was no ordinary pigeon. Observing that engineers were busily filling in the holes, he hunkered down and patiently waited for the crew to finish the job. “Then he strutted majestically over the new made highway,” the awestruck engineers reported to their colleagues. The audacity of this bird must be admired

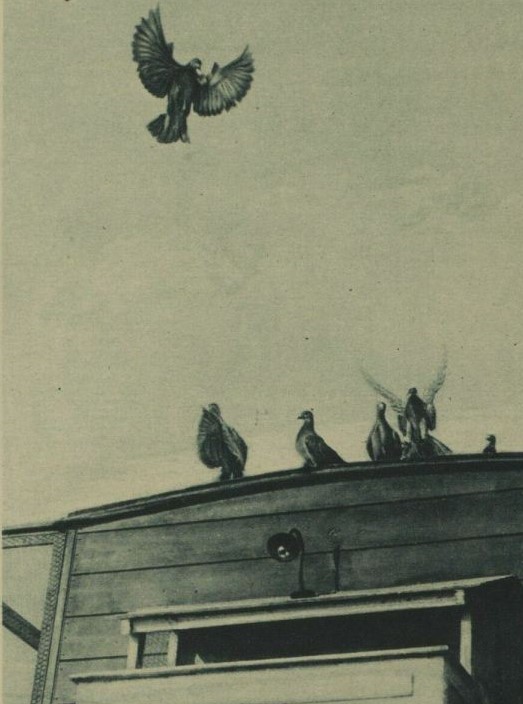

After his jaunty saunter along the Vesle, Old Satchelback’s superiors grounded all future flights and confined him to the coop permanently. Such a lackadaisical attitude toward flying typically would be grounds for culling. Yet something about Old Satchelback delighted his superiors. He was “a constant source of amusement” to them, possessing a “genial” temperament. His loft mates were likewise captivated by his attitude toward life. Recognizing the bird’s influence amongst his peers, Old Satchelback’s trainers recruited him for a special task: escorting shell-shocked pigeons back to the coop. The constant barrage of shellfire often upset the birds as they flew back to HQ. Whenever one arrived at the coop, it was common for the pigeon to circle nervously over it repeatedly without entering. This delayed officials from reading important battlefield dispatches, putting hundreds of soldiers’ lives at risk. Old Satchelback would be released at this point and join his companion in the air. Circling around the bird, he would then lead it back to the loft. If the pigeon failed to follow, Old Satchelback would try again repeatedly until it returned home. By the second or third attempt, the pigeon almost always tagged along.

Old Satchelback didn’t save hundreds of lives like Cher Ami. Unlike Lady Ethel, he was neither exceptionally fast nor dependable. He could barely do his job. Nevertheless, he brought joy to his commanders and comfort to traumatized pigeons. We at Pigeons of War believe this qualifies him for inclusion in the history books.

Sources:

- “France Gives Birds Pension,” The Bend Bulletin, Oct. 22, 1918, at 4.

- “They Winged Their Way Through Skies of Steel,” The American Legion Weekly, Vol. 1, No. 9, Aug. 29, 1919, at 30.