Pigeons and radio—their relationship is complicated, to say the least. Before radio—or wireless telegraphy, as it was initially known—first burst onto the scene, few methods of reliable, long-distance communication were available in areas unsuited for telegraph cables, such as the sea or mountainous terrain. Outside of sending a mounted rider or dispatch vessel, those wanting to send a message had to make due with flags or loud noises, balloons or pigeons. The first three had visibility limits of 10 miles (16 kilometers), while pigeons could deliver a message from 150 miles (241 kilometers) away at 25 to 40 mph. Clearly, a pigeon service was the superior medium for communicating with remote or inhospitable locations.

That all changed in the summer of 1898. On July 21-22, Guglielmo Marconi set up his wireless telegraph system aboard a steamer and broadcasted in real-time the results of the annual Kingstown Regatta yacht races. It didn’t take long for prognosticators to declare the imminent death of the pigeon post. The benefits were obvious. Wireless offered two-way communication. Wireless didn’t need to be fed or watered. It could be used at night. It didn’t have any natural predators.

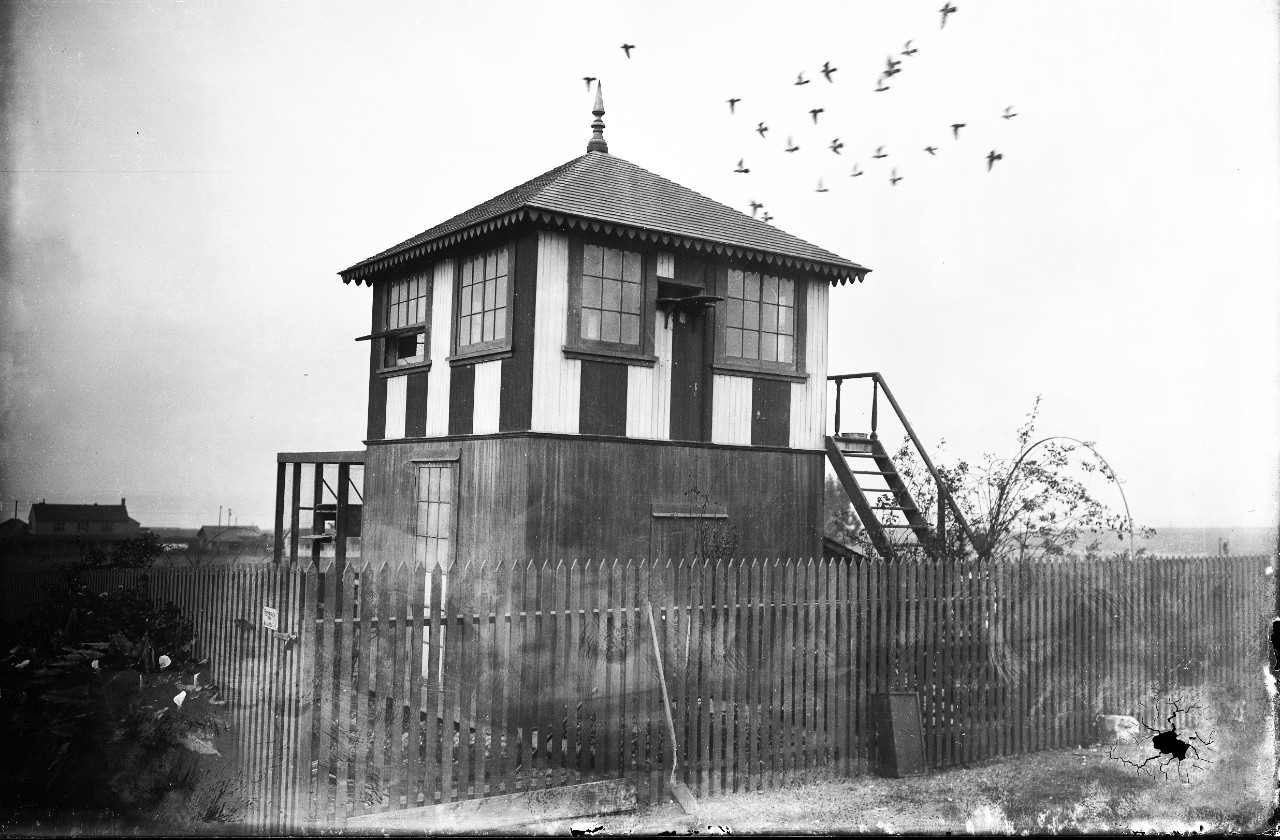

Navies quickly gravitated toward wireless telegraphy. With wireless systems, ships could communicate with the shore or ships at sea. As a consequence, naval officials rushed to disband their pigeon services. In 1901, the US Navy shut down its pigeon service in favor of wireless. The old pigeon coop at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Northern California was converted to a radio shack by 1904. The British and German navies would follow suit in 1908 and 1909.

Armies weren’t so quick to jettison their pigeons. At the outset of the Great War, the majority of the belligerents maintained pigeon services and would continue to do so throughout the conflict. That’s not to say they weren’t eager to deploy their new wireless units in battle. Indeed, the German Army invested heavily in the new technology, supplying every Army HQ and cavalry division with sets. But issues they encountered prompted them to keep pigeons available for backup.

An initial concern was the general scarcity of wireless sets. As it was a relatively new technology, most armies possessed only a handful. When the British Expeditionary Force landed in France in August 1914, for instance, it had only one portable set crammed into the back of a truck. A month later, the BEF had just ten units. Even as armies purchased more sets, it still was a very specialized piece of equipment that could be assembled by only just a few companies in the world. Pigeons, in contrast, were plentiful and readily available from fancier groups all across Europe. Their ability to reproduce was also an asset.

Large and unwieldy, wireless sets also presented portability issues, a major obstacle for armies on the move. Two or three men were required to move a single set. Horses and mules likewise had a difficult time transporting the machines, and tanks and airplanes didn’t have enough room for a set weighing over 100 pounds. Pigeons were small and weighed just a few pounds, however. A single soldier could carry several in a knapsack or box on his back. Dozens more could be moved all at once with a mobile loft. Tanks and airplanes could easily accommodate a crate of pigeons.

Wireless stations brought unwanted attention to trenches as well. To receive and transmit messages, a basic trench wireless station required a thirty-feet high mast with aerials. For enemy aircraft flying over trenches in search of targets, this was a godsend. Pigeon lofts were much more conspicuous; they could be concealed in out-of-the-way corners and easily camouflaged.

Finally, there were issues with the medium itself. Wireless transmissions often were unreliable and range was impacted by atmospheric conditions. They could be jammed or intercepted by the enemy, too. Users also had to know how to use Morse Code to send or receive messages. Pigeons had a success rate of 97% when flown during optimal conditions. Electronic devices could not be used to interfere with the birds or track their flights—“A pigeon silently flies through the air, there is no wave that indicates its use, nothing that indicates its point of departure or destination,” Lieutenant Colonel A.H. Osman, the head of the British Pigeon Service, reflected in his post-War memoir. No foreknowledge of a special cipher was required to handle pigeons, though it was well advised to use one in case a bird fell into enemy hands.

As the War drew to a close, radio finally overcame many of these early challenges, becoming an integral part of military operations. Yet pigeons had shown that they still had merit in the electronic age. Militaries, therefore, opted to keep their pigeon services after the War’s conclusion, retaining them through the Interwar Period and World War II. By the end of the ‘50s, radio communications had advanced to the point where pigeons seemed truly obsolete. Many militaries shuttered their pigeon services at this point. Radio had finally won the day.

Or so it would appear. Even in the twenty-first century—where radio waves sustain internet connections and communications satellites—pigeons can still rise to the occasion, should the opportunity arise. In rural areas, radio and internet are often unreliable at best and non-existent at worst. Natural disasters can also interrupt these services. For these reasons, the Odisha Police regularly used pigeons to carry dispatches between stations in East India into the 2000s. Military applications also continue to exist. Future conflicts will inevitably involve electronic warfare tactics, not unlike those encountered in the First World War. Keen to these threats, the French and Chinese armies each maintain a reserve of pigeons to be deployed in the event of war.

Perhaps pigeons and radio can coexist peacefully. One might even say they have a complementary relationship—Pigeons fill in the gaps when radio signals break down or can’t reach their intended destination. But, what if this relationship isn’t entirely benign? Is it possible that radio waves actually harm pigeons?

For over a century, fanciers living near radio stations have seen a diminishment in their homers’ navigational skills. In 1910, a prominent British fancier reported that his flock had been experiencing increasing losses ever since the advent of wireless telegraphy. He argued that it interfered with their homing instinct and even speculated that the waves themselves were killing his birds. An article from 1913 noted that whenever a pigeon race occurred near a wireless station, an unusual number of birds failed to find their way home. A raft of similar reports surfaced throughout the ‘20s and ‘30s, as radio stations popped up all over the country. These observations described a disturbing trend. As homing pigeons flew over a radio transmitter, they became disoriented, not knowing in which direction to fly. Once the birds passed over the antenna, the confusion dissipated. Shortwave radio signals—transmissions on frequencies between 3 to 30 MHz—intensified the symptoms, while broadcasts below 100 watts lessened them.

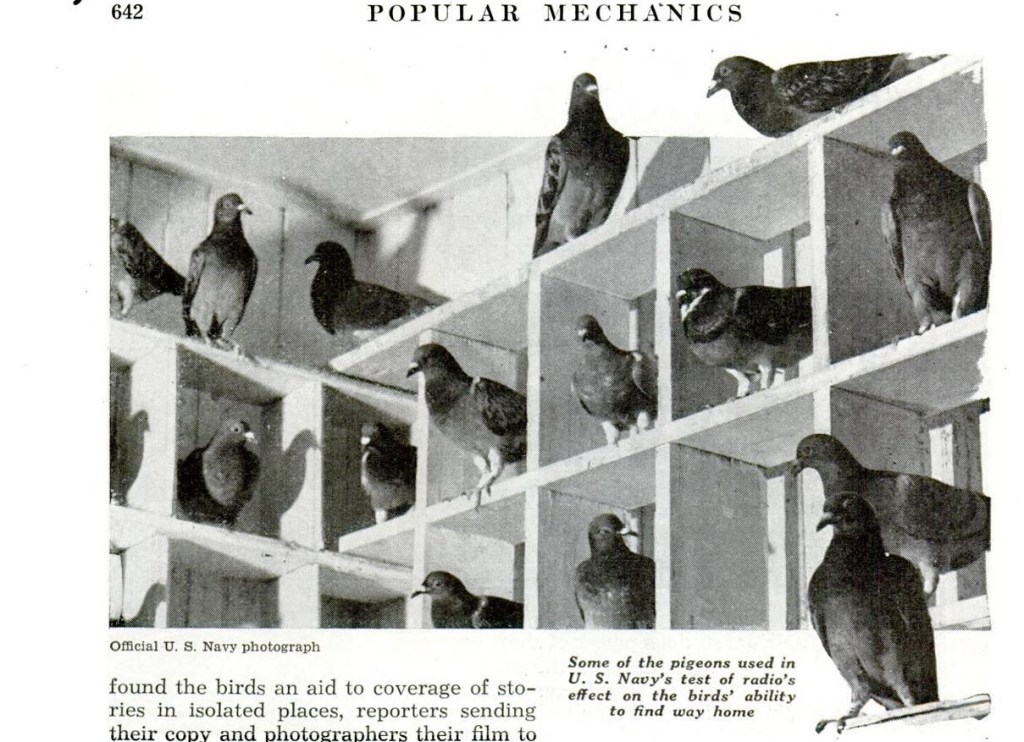

In 1937, the US Navy weighed in on the phenomena. Lieutenant George F. Watson, the officer in charge of the Navy’s loft at Lakehurst, New Jersey, investigated the effects of shortwave on the Navy’s birds. He released one set of birds near a shortwave radio station while it was transmitting, and another set fifteen minutes later after the station had stopped operating. Birds in the former group fluttered around the station in confusion for nearly twenty minutes, then made the ten-mile trip in forty-nine minutes, while the latter group made it in nineteen minutes. Two more trials achieved similar results. This gave naval officials heartburn, as it hinted at “the possibility that usefulness of the birds may be curtailed sharply.”

What was it about radio waves that caused them to harm pigeons? An early explanation invoked the concept of luminiferous ether, a hypothetical medium for the propagation of light. It was speculated that pigeons had a “sixth, or electric sense,” that was “in touch with the ether, that mysterious fluid which scientists declare to pervade everything in the universe on earth and in the air.” Per the thinking at the time, whenever radio waves traveled through the ether and interfered with “the ordinary waves of the ether,” such as light, it affected the birds’ sense of direction. After the ether theory had been consigned to the dustbin of history, later studies focused on magnetoreception. Pigeons, like all other migratory birds, have a magnetic compass hardwired into their brains that taps into the earth’s magnetic field, helping them find their way home. A study published in 2014 concluded that exposure to frequencies of up to 5 MHz—a chunk of the spectrum that encompasses AM radio and some shortwave bands—could interfere with this internal compass. The amount of exposure necessary to trigger this was “equivalent to what a bird in flight might experience five kilometers away from a 50-kilowatt AM radio station.” One scientist has called for society to gradually abandon its use of the AM bands.

As we said at the beginning of this blog, pigeons and radio have a complicated relationship. It ranges from adversarial to complementary to harmful. In spite of all predictions to the contrary, though, radio has yet to best pigeons.

Sources:

- Barik, Satyasundar. “Delivered by Pigeon Post in Cuttack.” Return to Frontpage, The Hindu, 5 May 2018, https://www.thehindu.com/society/delivered-by-pigeon-post-in-cuttack/article23784652.ece.

- Blazich, Frank. “In the Era of Electronic Warfare, Bring Back Pigeons.” War on the Rocks, 26 Feb. 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/01/in-the-era-of-electronic-warfare-bring-back-pigeons/.

- Dubenskij, Charlotte. “World War One: How Radio Crackled into Life in Conflict.” BBC News, 18 June 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-27894944.

- “Golden Age of Radio in the US.” Radio on the Frontlines: WWI and WWII | DPLA, https://dp.la/exhibitions/radio-golden-age/radio-frontlines/?item=671.

- Hartley-Smith, Alan. Marconi Heritage, http://marconiheritage.org/ww1-land.html.

- LeRoc, Norman, “Ancient Air Messengers for Modern War,” American Squab Journal, Vol. 7, No. 6, June 1918, at 173.

- Kirschvink, Joseph, “Radio Waves Zap the Biomagnetic Compass,” Nature, Vol. 509, May 15, 2014, at 296-297.

- “Mare Island Naval Radio Station.” Naval History and Heritage Command, https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/nhhc/our-collections/photography/technology/communications/radio/ug-21–us-naval-california-radio-station-collection/mare-island-naval-radio-station.html.

- Morelle, Rebecca. “Electrical Devices ‘Disrupt Bird Navigation’.” BBC News, 7 May 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-27313355.

- Osman, A.H., Pigeons in the Great War, at 17 (1928).

- “Pigeons Delayed by Radio Waves,” Popular Mechanics, Vol. 68, No. 5, November 1937, at 642.

- “Radio Affects Pigeon Flight,” The Santa Fe New Mexican, Oct. 10, 1924, at 4.

- “Radio Waves Said to Affect Pigeons of Homing Variety,” Belleville Daily Advocate, Aug. 17, 1937, at 2.

- “Wireless Waves Kill Birds,” The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Sept. 4, 1910, at 7.

- “Wireless Telegraphy.” New Articles RSS, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/wireless_telegraphy.

- “Wireless Worries Birds,” The Birmingham News, Dec. 7, 1913, at 41.