A lot of ink has been spilled about military pigeons and their heroic actions during wartime. But what about those in peacetime armies? This blog is the first part in an occasional series examining military pigeon services in countries with strong traditions of neutrality.

With a tradition of neutrality dating back to the 1500s, it may come as a shock to some that Switzerland has a proud military heritage. The Swiss Armed Forces boasts over 100,000 servicemembers, most of whom are conscripts. It has an Army and an Air Force. A flotilla of military boats patrols the nation’s many lakes. A fascinating aspect of the country’s military history is its long-time use of homing pigeons. Many countries discarded their pigeon services after World War II—the Swiss Army maintained theirs until the 1990s. Although their pigeons never saw conflict, they provided invaluable services for over 77 years.

The Swiss military first began experimenting with pigeons in 1879. The results were not encouraging—the birds refused to fly over high mountains, elements that cannot be avoided in Switzerland. Over the next few years, trainers developed better birds and training programs, which led to improved results. The Federal Council took notice of these developments and, in 1889, ordered the creation of a nationwide pigeon service. The aim of the service was to ensure communication amongst the country’s forts in the event of an invasion by the German or Austro-Hungarian Empires. Stations were set up at forts in Basel, Zurich, and Weesen, a small village abutting Lake Wallenstadt. These were served by a central station in Thun. Each station had 120 birds, but in the case of a large war, the Swiss military planned to requisition pigeons from local fancier associations. During these early years, officials worried that marauding hawks would prey upon pigeons while they were carrying important messages. The government officially branded birds of prey an enemy of the state. Cantons offered bounties of up to four Swiss francs per bird.

While the Great Powers clashed during WWI, Switzerland rapidly expanded the presence of pigeons in its military. Reports circulated that the German military had developed listening stations that could intercept telephone conversations from up to ten kilometers away. Fearing interception of its military’s confidential messages, on August 27 1917, the Federal Council directed the military to set up a pigeon service. A fully separate unit was created to supply pigeons for the Army, the Swiss Army Carrier Pigeon Service. Officers and soldiers, as well as members of the auxiliary and volunteer forces, cared for the pigeons and provided technical advice. This arrangement lasted until 1951, when the Service was reorganized and placed under a telecommunications unit, where it would remain until its decommissioning. From 1940 onward, women served in the unit, a feature absent from other military pigeon posts.

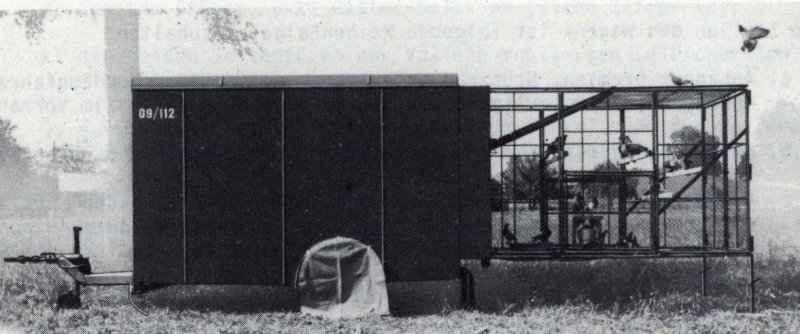

Throughout its existence, the Swiss Carrier Pigeons Service would maintain nearly 3,000 birds in twenty-three lofts scattered across the Alps and Jura regions. Eight mobile lofts were also available for flexible operations. Initially little more than horse-drawn carts, in 1959, a four-wheeled trailer that could house sixty-four birds was adopted by the Service. Aside from the pigeons it owned, the Army had access to nearly 30,000 birds, thanks to the patriotism of private fanciers. Indeed, since 1902, fanciers groups had entered into contracts with the government to turn over their pigeons in case of war or peacetime disasters. In exchange, the Army provided private breeders with free pigeon food and reimbursements for small expenses.

Working together, the Army and private fanciers devised breeding and training programs to develop pigeons acclimated to the country’s diverse landscape. A loft in the Sand-Schönbühl area served as the breeding depot for the Army’s birds. To safeguard breed standards, the military exercised tight control over the types of birds fanciers could raise—no pigeons could be imported into the country, absent express permission from the military. The Army’s training exercises involved regularly flying the birds over river valleys, forests, and mountains. Private fanciers had to ensure that their birds were fit for duty, too. Each year, their pigeons were subjected to a two-week refresher course in which they were transported via train to a border city hundreds of kilometers away and released; as they flew back home, the birds traveled extensively over mountain ranges.

A top-tier bird emerged from these intense breeding and training efforts. Dubbed Columba militaris helvetica, this breed was robust and highly adaptable, ideal traits for flights over mountainous terrain. The achievements of these birds are absolutely staggering. They could travel over 800 kilometers at speeds of 60 to 120 kilometers per hour, with 98% of them returning to their lofts. More than a third of the pigeons at one particular loft learned to fly at night. Some birds successfully made two-way flights and even three-way flights! Bird-for-bird, the Swiss Army had perhaps the most elite pigeon force the world had ever seen.

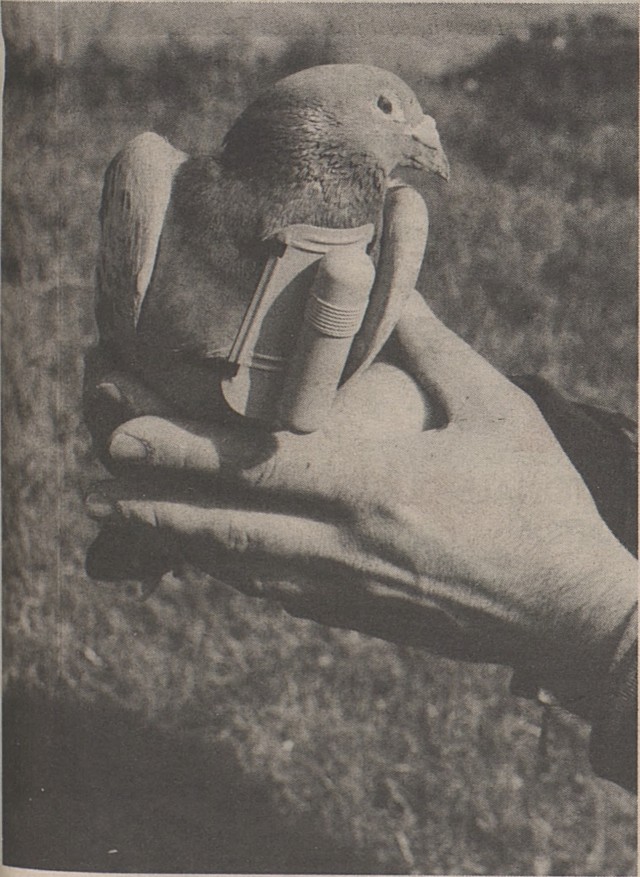

Given Switzerland’s firm commitment to neutrality, the Service’s pigeons largely served the needs of a peacetime Army. The birds guaranteed communication in times of catastrophe and from remote or difficult to access observation posts. They also served as couriers, delivering not only messages, but also sketches, photos, and microfilm to other stations. Because the birds could carry messages hundreds of miles away from their loft, their use as couriers freed up soldiers and vehicles for other work and saved on the cost of gas. But the threat of war could not be totally discounted. As the century progressed, threats of a German attack gave way to fears that the Soviet Union could invade from the northeast. To that end, soldiers, bicycle troops, and cavalry scouts frequently carried pigeons on their backs as they performed reconnaissance exercises.

At the start of the 1990s, Switzerland was the last European country to maintain a military pigeon service. But with the end of the Cold War, officials were eager to slash the Army’s budget. Many questioned why there was even a need for pigeons in a modern military. Servicemembers defended their pigeons, noting that the birds were cheap, not susceptible to electronic tracking or interference, and environmentally friendly—They were ”small, self-replicating biological missiles,” per Army regulations.

In spite of these advantages, the beancounters won out. On September 22, 1994, the Ministry of Defense officially decommissioned the Swiss Army Carrier Pigeon Service. Financial concerns were cited as the primary cause; the Service cost around 600,000 Swiss francs a year to operate. Officers and soldiers—including the head of the Service—received no advance notice whatsoever, hearing of the news once it had reached the media. The public was outraged to learn that the popular Service would be disbanded. To many, it brought back memories from the ‘70s, when officials dissolved the cavalry. Fanciers were especially incensed at this turn of events; after all, they had invested time and energy into training their birds for military service. They tried to collect enough signatures for a federal ballot initiative to preserve the Service, but nothing came of it.

The Service was granted a two-year transitional period to wind down its affairs. Dozens of the birds were auctioned off to breeders in Germany, France, and South Africa. Local fanciers, however, couldn’t bear the thought of losing such a unique breed. They pooled together their resources and set up a charitable foundation for the purpose of preserving Columba militaris helvetica for science and sport. The foundation entered into negotiations with the Army and eventually reached an agreement. Under the terms of the arrangement, the foundation would obtain the remainder of the pigeons and their equipment, and lease the Sand-Schönbühl pigeon station from the Army at a modest rent. On July 2, 1996, the Service officially ceased functioning.

The retired pigeons spent their final years at their old station. True to its mission statement, the foundation made the birds available for scientific study and sporting purposes. Scientists, aware of the pigeons’ unparalleled navigational abilities, recruited them for migration studies. Experiments were designed to track the birds’ flight paths, with the goal of clarifying how orientation cognition relates to the homing instinct. An annual summer racing contest—the Swiss Sand Derby—was launched by the foundation in its first year. Featuring the Army’s old birds as well as civilian pigeons, the races provided much needed funding for the lofts.

The foundation has also endeavored to preserve the breed. As of 2013, fifty descendants of the veteran flyers could be found in the Sand-Schönbühl station’s lofts. It is not an entirely risk-free life—hawks and martens occasionally target the birds. And, yet, this seems somewhat appropriate, considering the pigeons’ military heritage.

Swiss National Day is observed on August 1st each year. Only an official holiday since 1994—the same year the Swiss Army Carrier Pigeon Service was decommissioned—it is a day set aside to celebrate the founding of Switzerland. We here at Pigeons of War will be thinking of Columba militaris helvetica on that day.

Sources:

- A Tough Day for Pigeons. Tampa Bay Times, 23 Sept. 1994, https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1994/09/23/a-tough-day-for-pigeons/

- Auflösung Des Brieftaubendienstes Abgeschlossen, 2 July 1996, https://www.admin.ch/cp/d/1996Jul17.170649.6345@idz.bfi.admin.ch.html

- Bauer, Felix. Schweizer Armee Mustert Ihre Brieftauben Aus . Die Welt, 7 June 1996, https://www.welt.de/print-welt/article650105/Schweizer-Armee-mustert-ihre-Brieftauben-aus.html?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc.

- Bundesamt für Uebermittlungstruppen, Die Brieftaube alsUebermittlungsmittel unserer Armee, https://hamfu.ch/_upload/Brieftauben-Weisung-BAUEM.pdf?_x_tr_sl=de&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

- Cadetg, Leonhard, Der Brieftaubendienst, Pionier : Zeitschrift für die Übermittlungstruppen, (1988).

- Die Brieftaube im Dienste unserer Armee, Schweizer Soldat : Monatszeitschrift für Armee und Kader mit FHD-Zeitung, (1928-1929).

- Genuth, Iddo. “Computer Controlled Pigeon.” TFOT, 16 Feb. 2007, https://thefutureofthings.com/5459-computer-controlled-pigeon/

- Interessengemeinschaft Übermittlung (IG Uem): Brieftaubendienst der Schweizer Armee

- Kroon, Robert L. “Swiss Budget Cutters Clip Army’s Platoon of Carrier Pigeons.” New York Times, December 23, 1994.

- Leybold-Johnson, Isobel. High-Tech Pigeons Reveal Navigation Secrets. Swissinfo.ch, 25 Sept. 2017, https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/high-tech-pigeons-reveal-navigation-secrets/74794

- Lipp, Hans-Peter, Brieftauben in der Armee – ein Anachronismus? Krieg im Äther. Vorlesungen an der Eidgenössischen Technischen Hochschule in Zürich im Wintersemester (1979/1980).

- Nicolussi, Ronny. Die Nachkommen Der Letzten Armee-Brieftauben . Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 2 Mar. 2013, https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/die-nachkommen-der-letzten-armee-brieftauben-ld.1021393

- “Protection of Military Carrier Pigeons,” The Auk, Vol. 35, 1918, at 253.

- Schmidlin, Rita, Brieftaubendienst: Gestern – heute – morgen, MFD-Zeitung, October 1992, at 50-52.

- “Swiss Army Pigeons Sold to South Africa, UPI, July 25, 1995.

- Tribelhorn, Marc. Schweizer Armee: Brieftauben Vor 25 Jahren Ausgemustert. Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 23 Sept. 2019, https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/schweizer-armee-brieftauben-vor-25-jahren-ausgemustert-ld.1510477?reduced=true