To get a message delivered under wartime conditions is no easy feat. As readers of this blog are well aware, this responsibility is often borne entirely on the wings of homing pigeons. But dogs have been used as messengers in combat, too. While soldiers are quite capable of running messages between units, a human runner is often too valuable a resource to spare. Dogs are plentiful, given their fecundity—thus, they are more disposable. They also possess myriad advantages over humans. A dog is much quicker than even the most agile soldier, running as fast as five kilometers in under fifteen minutes. Dogs have a keener sense of hearing and smell than humans and can see better in the dark. One instruction guide for combat dog handlers rhapsodized over their beneficial traits:

He is surer and faster; he can find his way in daylight and darkness, in any kind of weather, over rough or smooth terrain, open or jungle country, at high altitude, and in snow or cold. He can carry a message up to 1 mile at great speed. He is a difficult target, due to size, speed, and natural ability to take advantage of cover.

Dogs aren’t without their limitations. Although good sprinters, dogs don’t fare well at long-distance treks. In the 1890s, the French military compared the speed of bicycles, horses, carrier pigeons, and dogs while on maneuvers. The pigeons arrived first and the dogs were dead last. Excessive familiarity with the animal renders it useless. As dogs are always popular with troops, this requires handlers to exercise constant vigilance.

During the latter-half of the nineteenth century, armies began incorporating dogs into their operations, with Germany leading the pack. Through trial and error, military dog schools developed a set of criteria for selecting the perfect messenger dogs. The ideal candidate needed to possess a high degree of intelligence and energy, stamina and loyalty. Unlike sentry, attack, or scout dogs, aggression was not necessary, though the dog would need to defend itself if captured. Because the dog needed to have a strong bond with only its handlers, it should be aloof toward strangers. As far as size, the dog should be small enough to avoid being a target, yet large enough to traverse difficult terrain. Although a variety of breeds met these standards, Airedale Terriers were valued the most by handlers, followed by German Shepherds.

In training them for message duty, military authorities typically divided the dogs into two sub-categories. Messenger dogs delivered a message from one point to another. They were simpler to train and required only one handler. Liaison dogs could travel back-and-forth between two handlers. As this task was more complex, it took longer to train the dogs. After training, the dogs were ready for combat service. Soldiers heading to the frontline would take a dog from its handler, who remained behind. When it was time to send a message, the soldiers placed a note in a pocket or tube on the dog’s collar and set it free. The dog then would run back to the last place it had been with its handler. If the dog had been trained for liaison service, it could be sent back to the frontline with a reply message for its second handler.

Why did militaries need to rely on dogs to carry messages when homing pigeons were available? After all, nearly every European military had a pigeon service at this point. When it came to long-distance transmission, the pigeon was superior to the dog in every way. However, if a dispatch needed to be transmitted over a short-distance—say a couple of miles—the inverse was true. Unlike pigeons, dogs could travel at night or in inclement weather. Dogs also weren’t rooted to a particular location; they could return to wherever they had last been with their keepers. Pigeons, in contrast, will only fly towards their home loft. This led to the most significant advantage: dogs could be trained to travel to and from a location, thus allowing for two-way communication between handlers.

Not every military had the resources for training liaison dogs, however. The British War Dog Service never trained its dogs for liaison work during the First World War—they simply could not spare the extra manpower. Even with liaison dogs, there was always the risk that the dog might get hurt and not return right away (or at all). Handlers, therefore, realized that if they trained their dogs to carry pigeons, the birds would complement the dogs’ messaging abilities. With pigeons, messenger dogs could maintain two-way communication between the frontline and HQ and liaison dogs had a better chance of getting a reply delivered. At a more utilitarian level, a dog trained to transport pigeons freed up soldiers and vehicles for other work.

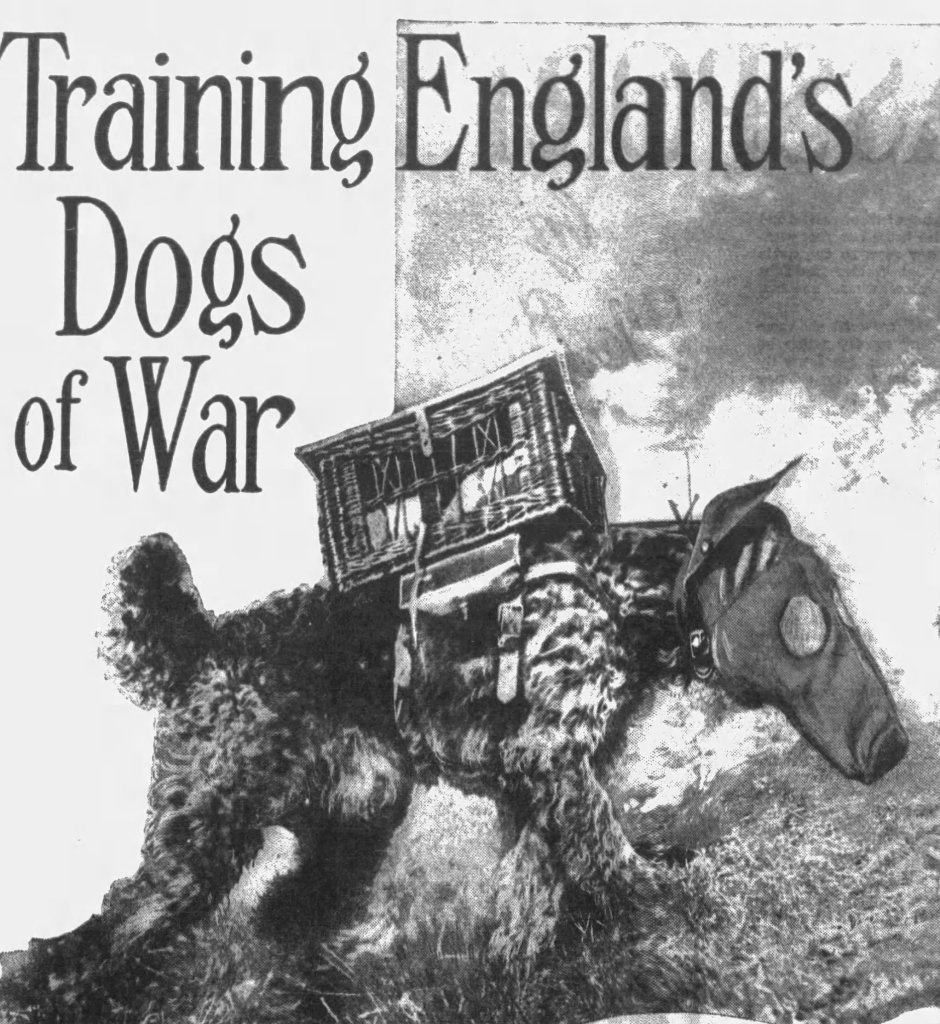

Throughout both World Wars, most of the armies employed messenger dogs. As the frontlines were often only a few miles from HQ, handlers paired their dogs with pigeons. These dogs faithfully carried their birds across trenches, under barbed wire, and through brush amidst constant gunfire, artillery barrages, and gas attacks. The methods by which the dogs transported the pigeons evolved over the years. Initially, dogs carried pigeons in wicker baskets strapped to their backs. A basket held three to six birds, which were fastened to the basket’s sides to provide resistance while the dog ran. Eventually, a harness was developed for securing pigeons around a dog’s mid-section. Some versions of the harness used side pouches, while others incorporated smaller wicker baskets. The US Army Signal Corps abandoned the use of harness baskets in 1944, after discovering that the birds bounced off the sides and damaged their feathers during the dogs’ training exercises. Handlers fashioned a softer medium out of the cardboard canisters of spent artillery shells.

The most celebrated account of a dog and pigeon working together occurred during the Verdun Offensive of 1916. Soldiers at a garrison had been ordered to defend a village at all costs, since it was located in a strategic spot. As the Germans advanced into the area, the garrison started to run out of ammunition. To make matters worse, the Germans organized a battery on a hill overlooking the village. Without reinforcements, the battery soon would wipe out the village and garrison. But communication with HQ was impossible; the garrison’s telegraph and telephone lines had been cut and their last homing pigeon had been shot out of the sky. The situation looked dire. Suddenly, a black dog wearing a gas mask and sporting “wings” on his shoulders came bounding across the village. A handler recognized the dog as one of his own: Satan, a greyhound-collie mix. In spite of his speed, the Germans managed to shoot Satan. The dog carried on, though, limping on three legs toward the soldiers. When they inspected the dog, they found a note from HQ promising that assistance would be sent within a day. They also noticed that Satan’s “wings” were actually pigeon baskets. The commandant rapidly scribbled out messages detailing the location of the German battery. The birds were released with the messages. The Germans shot down one before it had made it a quarter of a mile, but the other flew back to its loft. Within an hour, the garrison’s soldiers knew the village would be spared as they heard the thunder of French guns raining down upon the battery. Satan and the nameless pigeon had saved countless lives that day.

The title of this blog is Bird-Dogging, which means doggedly seeking out someone or something. As message bearers, that is the mission of dogs and pigeons in combat. The dog seeks out its handler, the bird its loft, while facing great peril. We are fortunate that these animals possess such single-minded devotion to the task at hand.

Sources:

- An Experiment with Teaming Pigeons and Dogs, United States Army Communications-Electronics Command, https://cecom.army.mil/PDF/Historian/Feature%202/Blog%20Teaming%20Pigeons%20and%20Dogs.pdf

- Baynes, Ernest Harold, Animal Heroes of the Great War, at 171, 179-182 (1925).

- ———. “Mankind’s Best Friend,” The Book of Dogs, at 17 (1919).

- Bird-dog.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bird-dog

- Brouwer, Sigmund, Innocent Heroes: Stories of Animals in the First World War, 79-80 (2017).

- “Dogs as Soldiers,” The Review of Reviews, Vol. 14, Jul. – Dec. 1896, at 530.

- “Dove of Peace Is Real Eagle of War,” San Francisco Chronicle, Oct. 31, 1920, at 5.

- “Heroic Dash of Dog, After Being Shot, Saves Lives of French Troop,” The Birmingham News, May 23, 1926, at 77.

- Kane, Gillian. “Meet Sergeant Stubby, America’s Original Dog of War.” Slate Magazine, Slate, 8 May 2014, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2014/05/dogs-of-war-sergeant-stubby-the-u-s-armys-original-and-still-most-highly-decorated-canine-soldier.html

- “Pigeons Carried By Dogs to Help in Training,” Popular Mechanics, Vol. 50, No. 5, Nov. 1928, at 800.

- Richardson, E.H., British War Dogs, at 75-75 (1930).

- War Department, “War Dogs,” Technical Manual No. 10-396, Jul 1, 1943, at 121.

One response to “Bird-Dogging: Pigeons & Dogs Working Together in War”

[…] View Source […]

LikeLike