On August 4, 1914, German troops marched across the Belgium border toward the fortified city of Liege. Germany had declared war on Belgium a day before, after the country had refused to grant the German Army safe passage through its territory. The first battle of the Great War began in the early hours of August 6th as the Germans launched an assault against Liege. After nearly three months of intense fighting, Germany occupied most of the country and would hold it for the duration of the War.

Post-War accounts have focused largely on the lurid events that allegedly occurred during the invasion and subsequent occupation, known collectively as the “Rape of Belgium.” One story, however, has not been fully addressed: How did the Belgian Pigeon Service (BPS) fare against the German military?

Belgium is the birthplace of the homing pigeon. Nearly all of the world’s prize-winning homers can trace their pedigrees back to Belgian fanciers. Simply put, Belgians love their pigeons, and, to this day, pigeon racing is considered the national sport.

It’s no great surprise, then, that in the years leading up to 1914, the Belgium Army had created a pigeon service for emergency communications. Indeed, nearly every other Great Power in Europe had done the same after the Franco-Prussian War. That War had shown the world that pigeons could deliver messages reliably when telegraph lines had been cut.

Established in 1896, the BPS was managed by the Army’s engineer corps. A commandant oversaw operations, supported by a staff of non-commissioned officers and privates. The principal loft was housed in the top floor of a stone mansion in Antwerp, right outside the ring of forts encircling the city. Secondary lofts were later built in Namur and Liege, located to the south of Antwerp. Each loft housed hundreds of birds. By 1914, Antwerp’s loft supposedly had ballooned to 2500 birds.

Unlike the majority of pigeon services in Europe, the BPS didn’t provide soldiers or cavalry scouts with birds to use while out in the field. Rather, the service existed solely to ensure communication amongst Belgium’s fortified cities in case telegraphic services were interrupted. Trainers at the Antwerp, Namur, and Liege lofts taught the birds to fly back from each city, which allowed for two-way communication between the three cities. The birds’ flight paths eventually extended to Dendermonde to the east and Diest to the west, linking more forts with the BPS.

The BPS also operated a photographic studio in Antwerp to prepare messages for transmission. The studio utilized a microphotographic process, similar to the one employed by Paris’ pigeon post during the Franco-Prussian War. Messages were written out on a large blackboard, photographed and reduced in size, and printed on small strips of celluloid film. A single, two-inch strip contained several columns of text. A pigeon could easily fly with a dozen or more strips stuffed into its leg holder. The recipient had the choice of either reading the despatches under a microscope or projecting them onto a screen.

On the eve of World War One, Belgium was considered by some to have “the finest pigeon service in the world.” Led by Commandant G. Genuit, the BPS was ready, willing, and able to provide vital services in the event of conflict.

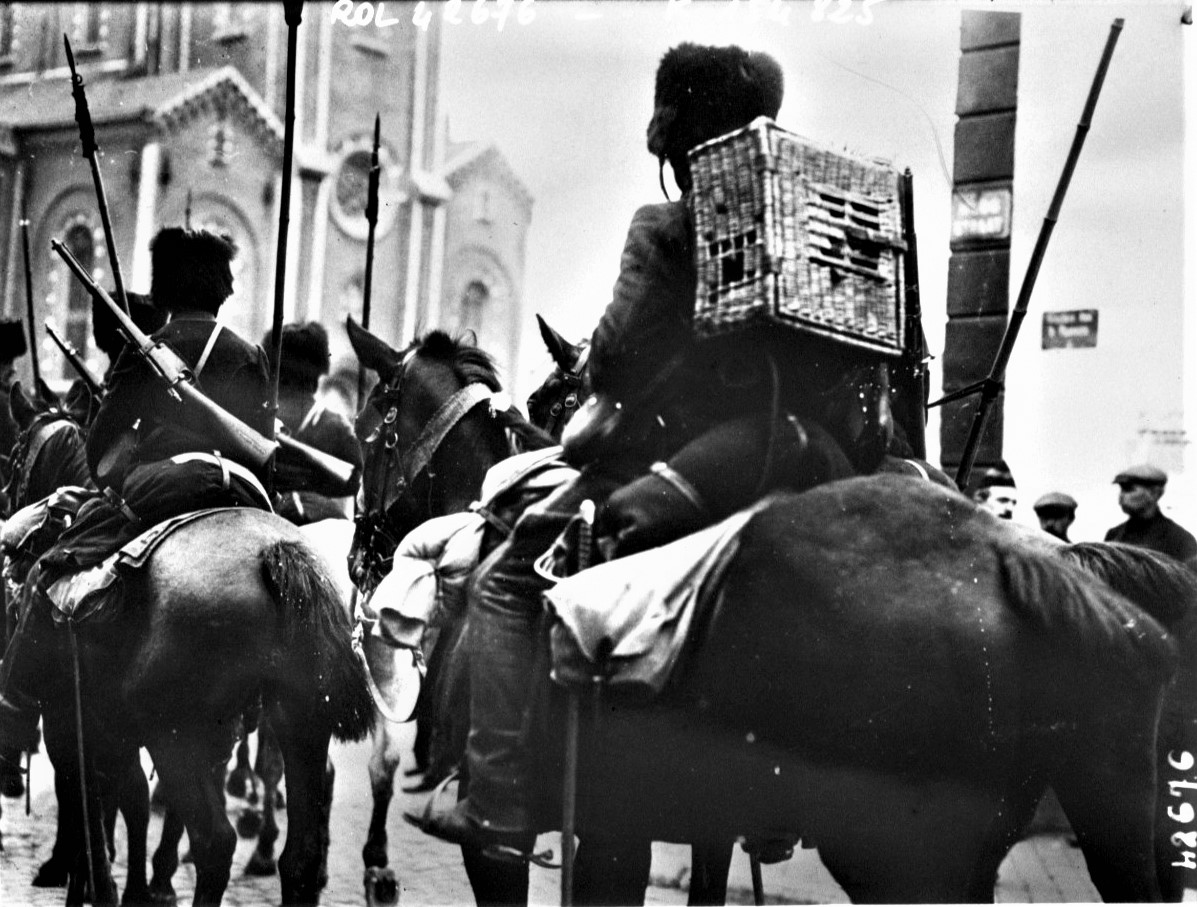

And, indeed, the pigeons served admirably in the opening weeks of the German invasion. A cipher was developed to conceal the meaning of messages, permitting encrypted reports to be passed between forts. The birds were also recruited for reconnaissance work. Scouts reconnoitering in occupied territory sent the birds back to the military lofts with tiny maps detailing German troop positions. This information helped the Belgian artillery inflict “heavy and unexpected casualties” on the Germans. German commanders were baffled—how had the Belgians discovered their positions so quickly? It took some time for them to realize pigeons were responsible for conveying this intelligence.

But Belgium’s fortresses could not withstand the might of the German artillery. Liege fell on August 16th. Namur surrendered nine days later. The government abandoned Brussels, while the Belgian Army retreated to Antwerp. The Germans occupied Brussels and ordered fanciers to destroy all of their carrier pigeons by September 15th or face a court martial. The Burgomaster of Brussels, however, convinced the German authorities to simply intern the birds in a public forum under German control. Hundreds of crates brimming with pigeons were deposited in one of the halls of the Parc du Cinquantenaire. Fanciers were permitted to feed their birds daily while German soldiers closely monitored their activities.

Antwerp was now in Germany’s cross-hairs. The siege of the city started on September 28th. Fierce fighting lasted for over a week. On October 8th, it was evident that German forces would take Antwerp by the end of the day. The Germans undoubtedly would confiscate the pigeons as spoils of war. Commandant Denuit had to act fast. He was forced to make a heart-wrenching decision. Writing eleven years later, Ernest Harold Baynes, an animal rights activist, described Denuit’s act of desperation:

[T]hat morning, with aching heart but with firm purpose, he took a torch and fired the great colombier, burning alive twenty five hundred of the finest pigeons in all the world, that they might not be forced into the service of the enemy. He was only just in time, for the Germans burst into the town at noon.

The city officially surrendered the following day.

Denuit’s great sacrifice prevented thousands of elite pigeons from falling into German hands. It was a tremendous blow to Denuit. Not only had he spent years of his professional life training the birds, he’d developed an intimate bond with them. Some accounts claim that he sobbed as he set the loft aflame.

During the occupation, the German military imposed strict conditions to prevent Belgians from using pigeons to aid resistance efforts. Pigeon fanciers and their lofts were kept under constant surveillance. Towns were fined thousands of francs whenever an inhabitant let loose a pigeon. Anyone caught using homers to send messages “regarding the movement of troops, troop trains or munitions” faced summary execution.

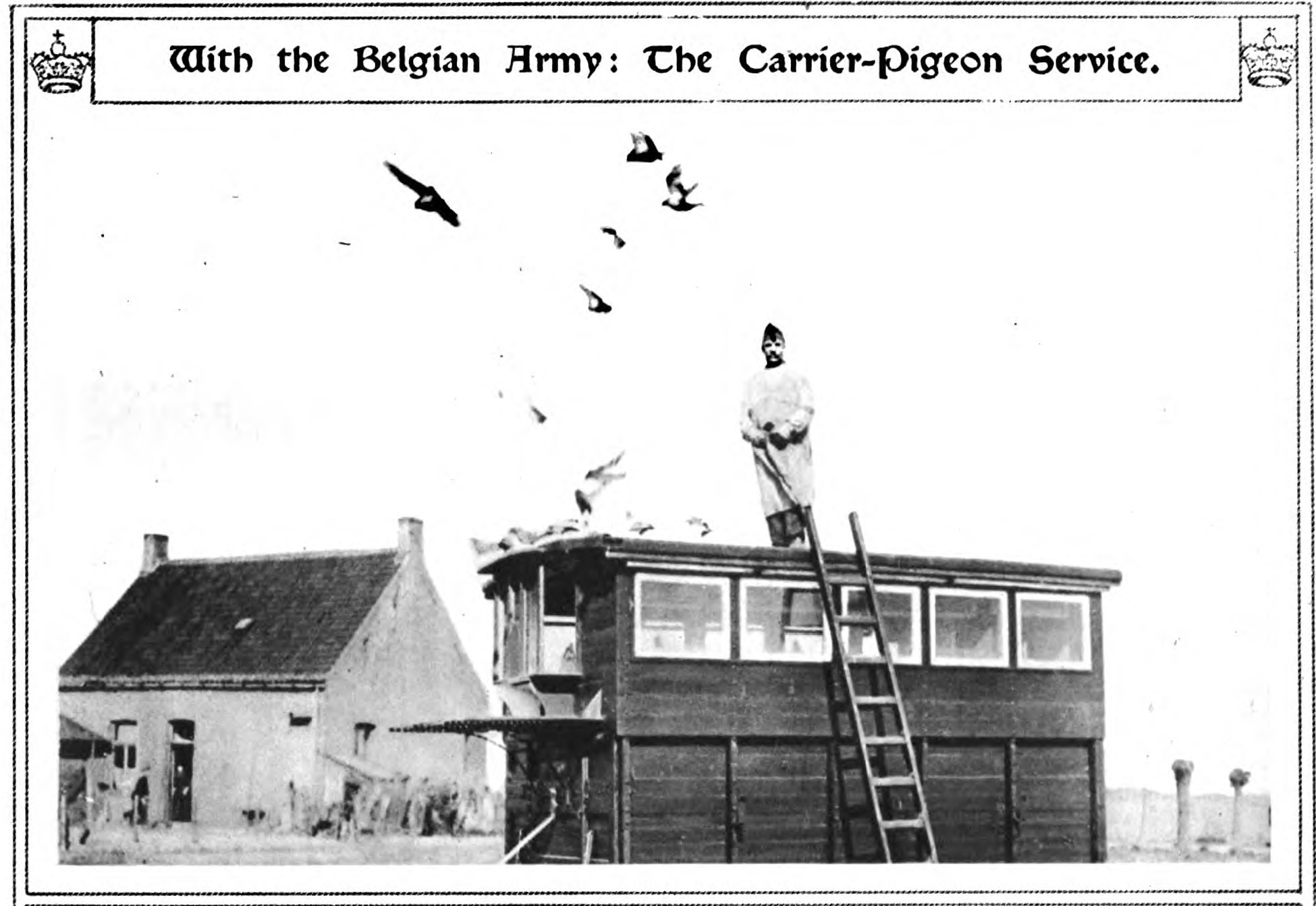

In spite of these actions, a new iteration of the BPS would soon reemerge in the only unoccupied piece of territory left in Belgium: a 19-mile strip of land near the North Sea coast. Rallied by King Albert, the remnants of the Belgian Army established a presence there and continued to fight against the occupying forces. By 1917, pigeons once again had been integrated into military operations. Mobile pigeon vans, similar to the ones used by the French, transported the birds to the front line, where they kept HQ apprised of developments. The BPS was so highly regarded that a Belgian Army officer—who just so happened to be an American citizen—was dispatched to help the Americans set up their own pigeon service after they’d arrived in Europe.

To answer the question posed earlier in this blog, all facts demonstrate that the BPS performed extraordinarily well in the face of incredible hardships. The pigeons provided crucial communication and surveillance services under wartime conditions, which undeniably aided the Belgian Army. The resiliency of Belgian fanciers and servicemembers must also be recognized. Despite every effort by the German military to dismantle the BPS, courageous Belgians risked life and limb to train pigeons for war service. The Monument au Pigeon-Soldat, a statue in Brussels commemorating the bravery of Belgium’s pigeons and citizens during World War One, serves as a fitting tribute to the BPS.

Sources:

- Baynes, Ernest Harold, Animal Heroes of the Great War, at 226-227 (1925).

- Corbin, Henry C. & Simpson, W. A., Notes of Military Interest for 1901, at 244 (1901).

- “Fleet Pigeons Used By Warring Forces to Reveal Enemy’s Secrets,” The Buffalo Sunday Morning News, Nov. 8, 1914, at 22.

- Fox, Frank, The Agony of Belgium, at 246 (1915).

- Kistler, John M., Animals in the Military, at 224 (2011).

- Marion, Henri, Report on Homing Pigeon System, at 11-12 (1897).

- Massart, Jean, Belgians Under the German Eagle, at 147 (1916).

- Naether, Carl A., The Book of the Racing Pigeon, at 55-56 (1944).

- Osman, Alfred Henry, Pigeons in the Great War, at 50 (1928).

- “Pershing’s Men Train Pigeons to Carry Notes,” The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer, Oct. 27, 1917, at 5.

- “Resourceful Belgians,” The Age, Aug. 17, 1914, at 7.

- Whitlock, Brand, Belgium Under German Occupation, at 183 (1919).

- “With the Belgian Army: The Carrier Pigeon Service,” The Illustrated War News, May 16, 1917, at 30.